Westward Into Kentucky: the Narrative of Daniel Trabue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 3 No. 1.1 ______January 2006

Vol. 3 No. 1.1 _____ ________________________________ _ __ January 2006 th Return to the Cow Pens! 225 Backyard Archaeology – ARCHH Up! The Archaeological Reconnaissance and Computerization of Hobkirk’s Hill (ARCHH) project has begun initial field operations on this built-over, urban battlefield in Camden, South Carolina. We are using the professional-amateur cooperative archaeology model, loosely based upon the successful BRAVO organization of New Jersey. We have identified an initial survey area and will only test properties within this initial survey area until we demonstrate artifact recoveries to any boundary. Metal detectorist director John Allison believes that this is at least two years' work. Since the battlefield is in well-landscaped yards and there are dozens of homeowners, we are only surveying areas with landowner permission and we will not be able to cover 100% of the land in the survey area. We have a neighborhood meeting planned to explain the archaeological survey project to the landowners. SCAR will provide project handouts and offer a walking battlefield tour for William T. Ranney’s masterpiece, painted in 1845, showing Hobkirk Hill neighbors and anyone else who wants to attend on the final cavalry hand-to-hand combat at Cowpens, hangs Sunday, January 29, 2006 at 3 pm. [Continued on p. 17.] in the South Carolina State House lobby. Most modern living historians believe that Ranney depicted the uniforms quite inaccurately. Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion cavalry is thought to have been clothed in green tunics and Lt. Col. William Washington’s cavalry in white. The story of Washington’s trumpeter or waiter [Ball, Collin, Collins] shooting a legionnaire just in time as Washington’s sword broke is also not well substantiated or that he was a black youth as depicted. -

The Virginia Historical Register, and Literary Companion

REYNOLDS HISTORICAC GENEALOGY COLLECTION ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1833 01763 2602 GENEALOGY 975.5 V8191B 1853 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center http://www.archive.org/details/virginiahistoric1853maxw THE VIRGIMIA HISTO RICAL REGISTER ] /fSS AND LITERARY COMPAJilON. EDITED BY WILLIAM MAXWELL, /. «^ VOL. VI. FOR THE YEAR 1853.^ RICHMOXD: • PRINTED FOR THE PROPRIETOR, BY jiACfAEiAyrVrEkiSbto', T ' 185cj CONTENTS OF VOLUME YI. NO. I. 1. Bridge, - - 1 The Battle of the Great j 2. Captain Cunningham, - - - 6 | 3' Smyth's Travels in Virginia, - - ^^1 4. The Virginia Gazette— Gazetteiana, No. 1, - 20 | 5. Tiiomas Randolph, - - - - 32 | C. Original Letter : from Gen'l Washington to Governor | Harrison, - - - - - ^"^ f 7. Architecture in - » - Virginia, 37 | 8. Stove - - - '42 The Old Again, . 9. The Late Miss Berry, - - - 45 I 10. INIenioirs of a Huguenot Family, - 45> 3 li. Various Intelligence: —The Sixth Annual INIeeting of | the Virginia Historical Late Daniel Society—The | Webster—A Curious Relic—The Air Ship— Gait's | - Pysche Again. - - - 49 I 12. Miscellany :—Lines on Gait's Psyche—The Study of | Nature—An Old Repartee Done into Rhyme. - 59 I NO. IL I 1. The Capture of Vincennes, - - 61 | 2. Smyth's Travels in Virginia, in 1773, &c. - 77 3. Gazetteiana, No. 2, - - - 91 I 4. Wither's Lines to Captaine Smith, - 101 I 5. Turkoy L-land, - - - 103 6. Old Trees, - - - 106 ? 7. Lossing's Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution, 108 I 8. Various Intelligence : — Mineral Wealth of Virginia— | The New Cabinet— the Medical College— RaifRoads in Virginia —The Caloric Inventior. -

(Summer 2018) John Filson's Kentucke

Edward A. Galloway Published in Manuscripts, Vol. 70, No. 3 (Summer 2018) John Filson’s Kentucke: Internet Search Uncovers “Hidden” Manuscripts In 2010 the University Library System (ULS) at the University of Pittsburgh embarked on an ambitious mission: to digitize the content of the Darlington Memorial Library. Presented to the university via two separate gifts, in 1918 and 1925, the Darlington library has become the anchor of the Archives and Special Collections Department within the university library. Comprised of thousands of rare books, manuscripts, maps, broadsides, atlases, lithographs, and artwork, the library showcased the collecting passions of the Darlington family who lived in Pittsburgh during the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. The patriarch, William M. Darlington (1815-1889), was born in Pittsburgh and practiced law in Allegheny County. A passionate collector, William M. Darlington found his equal in Mary Carson O’Hara (1824- 1915), whom he married in 1845.1 They subsequently moved into a newly-constructed Italianate home just a few miles up the Allegheny River from Downtown Pittsburgh. Here, they raised three children, O’Hara, Mary, and Edith, all recipients of their parents’ love of history and bibliophiles to the core. Having married into a wealthy family, Mr. Darlington retired from his law career in 1856 to manage the estate of his wife’s grandfather, James O’Hara, whose land holdings encompassed a major portion of Pittsburgh.2 He would devote most of his adult life to collecting works of Americana, especially that which documented western Pennsylvania. Even the land upon which he built his estate, passed down to his wife, dripped with history having been the last home of Guyasuta, a Seneca chief.3 The Darlingtons eventually amassed the “largest private library west of the Alleghenies” containing nearly 14,000 volumes. -

Topography Along the Virginia-Kentucky Border

Preface: Topography along the Virginia-Kentucky border. It took a long time for the Appalachian Mountain range to attain its present appearance, but no one was counting. Outcrops found at the base of Pine Mountain are Devonian rock, dating back 400 million years. But the rocks picked off the ground around Lexington, Kentucky, are even older; this limestone is from the Cambrian period, about 600 million years old. It is the same type and age rock found near the bottom of the Grand Canyon in Colorado. Of course, a mountain range is not created in a year or two. It took them about 400 years to obtain their character, and the Appalachian range has a lot of character. Geologists tell us this range extends from Alabama into Canada, and separates the plains of the eastern seaboard from the low-lying valleys of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Some subdivide the Appalachians into the Piedmont Province, the Blue Ridge, the Valley and Ridge area, and the Appalachian plateau. We also learn that during the Paleozoic era, the site of this mountain range was nothing more than a shallow sea; but during this time, as sediments built up, and the bottom of the sea sank. The hinge line between the area sinking, and the area being uplifted seems to have shifted gradually westward. At the end of the Paleozoric era, the earth movement are said to have reversed, at which time the horizontal layers of the rock were uplifted and folded, and for the next 200 million years the land was eroded, which provided material to cover the surrounding areas, including the coastal plain. -

Henry Clinton Papers, Volume Descriptions

Henry Clinton Papers William L. Clements Library Volume Descriptions The University of Michigan Finding Aid: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/clementsead/umich-wcl-M-42cli?view=text Major Themes and Events in the Volumes of the Chronological Series of the Henry Clinton papers Volume 1 1736-1763 • Death of George Clinton and distribution of estate • Henry Clinton's property in North America • Clinton's account of his actions in Seven Years War including his wounding at the Battle of Friedberg Volume 2 1764-1766 • Dispersal of George Clinton estate • Mary Dunckerley's account of bearing Thomas Dunckerley, illegitimate child of King George II • Clinton promoted to colonel of 12th Regiment of Foot • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot Volume 3 January 1-July 23, 1767 • Clinton's marriage to Harriet Carter • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton's property in North America Volume 4 August 14, 1767-[1767] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Relations between British and Cherokee Indians • Death of Anne (Carle) Clinton and distribution of her estate Volume 5 January 3, 1768-[1768] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton discusses military tactics • Finances of Mary (Clinton) Willes, sister of Henry Clinton Volume 6 January 3, 1768-[1769] • Birth of Augusta Clinton • Henry Clinton's finances and property in North America Volume 7 January 9, 1770-[1771] • Matters concerning the 12th Regiment of Foot • Inventory of Clinton's possessions • William Henry Clinton born • Inspection of ports Volume 8 January 9, 1772-May -

Contents a Biography of Colonel John Hinkson

Spring 2000 Publication of the Ruddell and Martin Stations Historical Association Special Edition The Ruddlesforter is a publication by and for individuals interested in the Contents preservation of the history of these significant Revolutionary War forts. For further information contact: Ruddell and Martin Stations A Biography of Colonel John Hinkson Historical Association Rt. 4 123AAA (1729-1789) Falmouth, KY 41040 Pennsylvania and Kentucky Frontiersman 606 635-4362 Board of Directors By Robert E. Francis Don Lee President [email protected] Introduction 2 Martha Pelfrey Vice President The Early Years 3 Don Lee Life in Pennsylvania 3 Secretary/Treasurer [email protected] The Wipey Affair 4 Bob Francis Archives [email protected] Dunmore’s War 6 Jim Sellars Editor [email protected] Kentucky Expedition and Settlement: 7 Spring 1775 – Summer, 1776 Jon Hagee Website Coordinator [email protected] The Revolutionary War 9 Membership application: http://www.webpub.com/~jhagee/ The Capture of Ruddell’s and Martin’s Forts 10 rudd-app.html June 24 – 26, 1780 Ruddle’s and Martin’s Stations Web Site: http://www.shawhan.com/ruddlesfort.hml The Last Decade 14 Join the Ruddlesfort discussion group at: Bibliography 15 [email protected] (send an e-mail with the word “subscribe” in the message and you’ll be on the Appendix 17 mailing list – its free!) No part of this biography may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without express written permission of the author. RAMSHA/Bob Francis © 2000 A Biography of Colonel John Hinkson (1729-1789) Pennsylvania and Kentucky Frontiersman By Robert E. -

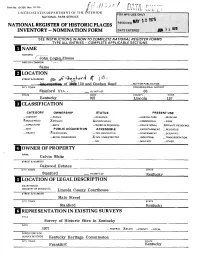

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC ^-CLogar^/House I LOCATION STREET & NUMBER U. VJUOlltUl -LXUctU CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Stanford (}{<-• _ VICINITY OF 05 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Kentucky 021 Lincoln 137 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM XBUILDINGIS) X.PRIVATE X.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS — EDUCATIONAL -XPRIVATE RESIDENCE _SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT 2ilN PROCESS — YES: RESTRICTED _ GOVERNMENT _ SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY _ OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Calvin„ , . White„„ STREET & NUMBER Oakwood Estates CITY, TOWN STATE Stanford VICINITY OF Kentucky LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Lincoln QOUnty STREETS NUMBER Main Street CITY, TOWN STATE Stanford Kentucky REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Historic Sites in Kentucky DATE 1971 —FEDERAL XSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Kentucky Heritage Commission CITY, TOWN STATE Frankfort Kentucky DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE .EXCELLENT X.DETERIORATED UNALTERED JXORIGINALSiTE .GOOD _RUINS X.ALTERED _MOVED DATE. .FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The John Logan House is located on Logan1 s Creek at the mouth of St. Asaph's Branch. The house is situated a mile east of the center of Stanford on the old east-west road between Stanford and Rowland on U.S. Highway 150, known as the Old Wilderness Road. -

Some Revolutionary War Soldiers Buried in Kentucky

Vol. 41, No. 2 Winter 2005 kentucky ancestors genealogical quarterly of the Perryville Casualty Pink Things: Some Revolutionary Database Reveals A Memoir of the War Soldiers Buried True Cost of War Edwards Family of in Kentucky Harrodsburg Vol. 41, No. 2 Winter 2005 kentucky ancestors genealogical quarterly of the Thomas E. Stephens, Editor kentucky ancestors Dan Bundy, Graphic Design Kent Whitworth, Director James E. Wallace, Assistant Director administration Betty Fugate, Membership Coordinator research and interpretation Nelson L. Dawson, Team Leader management team Kenneth H. Williams, Program Leader Doug Stern, Walter Baker, Lisbon Hardy, Michael Harreld, Lois Mateus, Dr. Thomas D. Clark, C. Michael Davenport, Ted Harris, Ann Maenza, Bud Pogue, Mike Duncan, James E. Wallace, Maj. board of Gen. Verna Fairchild, Mary Helen Miller, Ryan trustees Harris, and Raoul Cunningham Kentucky Ancestors (ISSN-0023-0103) is published quarterly by the Kentucky Historical Society and is distributed free to Society members. Periodical postage paid at Frankfort, Kentucky, and at additional mailing offices. Postmas- ter: Send address changes to Kentucky Ancestors, Kentucky Historical Society, 100 West Broadway, Frankfort, KY 40601-1931. Please direct changes of address and other notices concerning membership or mailings to the Membership De- partment, Kentucky Historical Society, 100 West Broadway, Frankfort, KY 40601-1931; telephone (502) 564-1792. Submissions and correspondence should be directed to: Tom Stephens, editor, Kentucky Ancestors, Kentucky Histori- cal Society, 100 West Broadway, Frankfort, KY 40601-1931. The Kentucky Historical Society, an agency of the Commerce Cabinet, does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, religion, or disability, and provides, on request, reasonable accommodations, includ- ing auxiliary aids and services necessary to afford an individual with a disability an equal opportunity to participate in all services, programs, and activities. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75-6523 HEMBREE, Charles William, 1939- NARRATIVE TECHNIQUE in the FICTION of EUDORA WELIY

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Windows Into Our Past a Genealogy of the Parsons, Smith & Associated Families, Vol

WINDOWS INTO OUR PAST A Genealogy Of The Parsons, Smith & Associated Families Volume One Compiled by: Judy Parsons Smith CROSSING into and Through THE COMMONWEALTH WINDOWS INTO OUR PAST A Genealogy Of The Parsons, Smith & Associated Families Volume One Compiled by: Judy Parsons Smith Please send any additions or corrections to: Judy Parsons Smith 11502 Leiden Lane Midlothian, VA 23112-3024 (804) 744-4388 e-mail: [email protected] Lay-out Design by: D & J Productions Midlothian, Virginia © 1996, Judy P. Smith 2 Dedicated to my children, so that they may know from whence they came. 3 INTRODUCTION I began compiling information on my family in 1979, when my Great Aunt Jo first introduced me to genealogy. Little did I know where that beginning would lead. Many of my first few generation were already set out in other publications where I could easily find them. Then there were others which have taken many years even to begin to develop. There were periods of time that I consistently worked on gathering information and "filling out" all the paperwork. Then there have been periods of time that I have just allowed my genealogy to set aside for a year or so. Then I something would trigger the genealogy bug and I would end up picking up my work once again with new fervor. Through the years, I have visited with family that I didn't even know that I had. In turn my correspondence has been exhaustive at times. I so enjoy sending out and receiving family information. The mail holds so many surprises. -

CHAPTER 3 the Classical School of Criminological Thought

The Classical CHAPTER 3 School of Criminological Thought Wally Skalij/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images distribute or post, copy, not Do Copyright ©2018 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. Introduction LEARNING A 2009 report from the Death Penalty Information Center, citing a study OBJECTIVES based on FBI data and other national reports, showed that states with the death penalty have consistently higher murder rates than states without the death penalty.4 The report highlighted the fact that if the death penalty were As you read this chapter, acting as a deterrent, the gap between these two groups of states would be consider the following topics: expected to converge, or at least lessen over time. But that has not been the case. In fact, this disparity in murder rates has actually grown over the past • Identify the primitive two decades, with states allowing the death penalty having a 42% higher types of “theories” murder rate (as of 2007) compared with states that do not—up from only explaining why 4% in 1990. individuals committed violent and other Thus, it appears that in terms of deterrence theory, at least when it comes deviant acts for most to the death penalty, such potential punishment is not an effective deterrent. of human civilization. This chapter deals with the various issues and factors that go into offend- • Describe how the ers’ decision-making about committing crime. While many would likely Age of Enlightenment anticipate that potential murderers in states with the death penalty would be drastically altered the deterred from committing such offenses, this is clearly not the case, given theories for how and the findings of the study discussed above. -

137 Covers 118 Covers.Qxd

The Emergence and Evolution of Memorial Day By Richard Gardiner, Ph.D., P. Michael Jones, and Daniel Bellware ABOUT THE AUTHORS P. Michael Jones has been the director of the General John A. Logan Museum in Murphysboro, Illinois, since 1989. His publications include The Life and Times of Major General John A. Logan (1996) and Forgotten Soldiers: Murphysboro’s African-American Civil War Veterans (1994). He is the recipient of the Illinois State Historical Society Lifetime Achievement Award and the Outstanding History Teacher award from Southern Illinois University. Daniel Bellware is an independent historical researcher in Columbus, Georgia. He is author of several articles on the American Civil War.Richard Gardiner, Ph.D. has been Associate Professor of History Education at Columbus State University since 2009. His publications include History: A Cultural Approach (2013) and several articles on history. This year commemorates the sesquicentennial anniversary of Decoration Day/Memorial Day (30 May). Today Memorial Day commemorates the men and women who sacrificed their lives in the military during war. It originally commemorated the conclusion of a war; designed to promote continued peace and reconciliation. It is our contention, however, that the narratives pertaining to the history and development of this holiday has been misinterpreted, misunderstood, and to many lost. The aim of this article is to provide a narrative in the interest of greater awareness and appreciation of the significance of the holiday. The story of the genesis of Memorial Day, an official holiday from May 1868, is not clear cut among historians, as it is traditionally taught.1 Though there are a multitude of apocryphal claims regarding who started Memorial Day and where they started it, the vast majority of accounts were manufactured many decades after the fact and are easily dismissed as myths.