Wang, Hua (2017) Origin and Network: Examining the Influence of Non- Local Chambers of Commerce in the Chinese Local Policy Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Nber Working Paper Series from Fog to Smog: the Value

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES FROM FOG TO SMOG: THE VALUE OF POLLUTION INFORMATION Panle Jia Barwick Shanjun Li Liguo Lin Eric Zou Working Paper 26541 http://www.nber.org/papers/w26541 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 December 2019, Revised January 2020 We thank Antonio Bento, Fiona Burlig, Trudy Cameron, Lucas Davis, Todd Gerarden, Jiming Hao, Guojun He, Joshua Graff Zivin, Matt Khan, Jessica Leight, Cynthia Lin Lowell, Grant Mc- Dermott, Francesca Molinari, Ed Rubin, Ivan Rudik, Joe Shapiro, Jeff Shrader, Jörg Stoye, Jeffrey Zabel, Shuang Zhang, and seminar participants at the 2019 NBER Chinese Economy Working Group Meeting, the 2019 NBER EEE Spring Meeting, the 2019 Northeast Workshop on Energy Policy and Environmental Economics, MIT, Resources for the Future, University of Alberta, University of Chicago, Cornell University, GRIPS Japan, Indiana University, University of Kentucky, University of Maryland, University of Oregon, University of Texas at Austin, and Xiamen University for helpful comments. We thank Jing Wu and Ziye Zhang for generous help with data. Luming Chen, Deyu Rao, Binglin Wang, and Tianli Xia provided outstanding research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2019 by Panle Jia Barwick, Shanjun Li, Liguo Lin, and Eric Zou. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

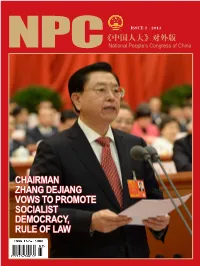

Issue 1 2013

ISSUE 1 · 2013 NPC《中国人大》对外版 CHAIRMAN ZHANG DEJIANG VOWS TO PROMOTE SOCIALIST DEMOCRACY, RULE OF LAW ISSUE 4 · 2012 1 Chairman of the NPC Standing Committee Zhang Dejiang (7th, L) has a group photo with vice-chairpersons Zhang Baowen, Arken Imirbaki, Zhang Ping, Shen Yueyue, Yan Junqi, Wang Shengjun, Li Jianguo, Chen Changzhi, Wang Chen, Ji Bingxuan, Qiangba Puncog, Wan Exiang, Chen Zhu (from left to right). Ma Zengke China’s new leadership takes 6 shape amid high expectations Contents Special Report Speech In–depth 6 18 24 China’s new leadership takes shape President Xi Jinping vows to bring China capable of sustaining economic amid high expectations benefits to people in realizing growth: Premier ‘Chinese dream’ 8 25 Chinese top legislature has younger 19 China rolls out plan to transform leaders Chairman Zhang Dejiang vows government functions to promote socialist democracy, 12 rule of law 27 China unveils new cabinet amid China’s anti-graft efforts to get function reform People institutional impetus 15 20 28 Report on the work of the Standing Chairman Zhang Dejiang: ‘Power China defense budget to grow 10.7 Committee of the National People’s should not be aloof from public percent in 2013 Congress (excerpt) supervision’ 20 Chairman Zhang Dejiang: ‘Power should not be aloof from public supervision’ Doubling income is easy, narrowing 30 regional gap is anything but 34 New age for China’s women deputies ISSUE 1 · 2013 29 37 Rural reform helps China ensure grain Style changes take center stage at security Beijing’s political season 30 Doubling -

News China March. 13.Cdr

VOL. XXV No. 3 March 2013 Rs. 10.00 The first session of the 12th National People’s Congress (NPC) opens at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, capital of China on March 5, 2013. (Xinhua/Pang Xinglei) Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei meets Indian Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Cheng Guoping , on behalf Foreign Minister Salman Khurshid in New Delhi on of State Councilor Dai Bingguo, attends the dialogue on February 25, 2013. During the meeting the two sides Afghanistan issue held in Moscow,together with Russian exchange views on high-level interactions between the two Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev and Indian countries, economic and trade cooperation and issues of National Security Advisor Shivshankar Menon on February common concern. 20, 2013. Chinese Ambassador to India Mr.Wei Wei and other VIP Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei and Indian guests are having a group picture with actors at the 2013 Minister of Culture Smt. Chandresh Kumari Katoch enjoy Happy Spring Festival organized by the Chinese Embassy “China in the Spring Festival” exhibition at the 2013 Happy and FICCI in New Delhi on February 25,2013. Artists from Spring Festival. The exhibition introduces cultures, Jilin Province, China and Punjab Pradesh, India are warmly customs and traditions of Chinese Spring Festival. welcomed by the audience. Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei(third from left) Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei visits the participates in the “Happy New Year “ party organized by Chinese Visa Application Service Centre based in the Chinese Language Department of Jawaharlal Nehru Southern Delhi on March 6, 2013. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript Pas been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissenation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from anytype of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material bad to beremoved, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with smalloverlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell &Howell Information Company 300North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106-1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521·0600 THE LIN BIAO INCIDENT: A STUDY OF EXTRA-INSTITUTIONAL FACTORS IN THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY AUGUST 1995 By Qiu Jin Dissertation Committee: Stephen Uhalley, Jr., Chairperson Harry Lamley Sharon Minichiello John Stephan Roger Ames UMI Number: 9604163 OMI Microform 9604163 Copyright 1995, by OMI Company. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement May 2007 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC .......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 44 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 45 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 52 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 May 2007 The Main National Leadership of the PRC -

Conference Digest

Conference Digest 2015 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation IEEE ICMA 2015 Beijing, China August 2 - 5, 2015 Cosponsored by IEEE Robotics and Automation Society Beijing Institute of Technology Kagawa University, Japan Technically cosponsored by The Institute of Advanced Biomedical Engineering System, BIT Intelligent Robotics Institute, Key Laboratory of Biomimetic Robots and Systems, Ministry of Education, BIT State Key Laboratory of Intelligent Control and Decision of Complex Systems, BIT Tianjin University of Technology Harbin Engineering University Harbin Institute of Technology State Key Laboratory of Robotics and System (HIT) The Robotics Society of Japan The Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers Japan Society for Precision Engineering The Society of Instrument and Control Engineers University of Electro-Communications University of Electronic Science and Technology of China Changchun University of Science and Technology National Natural Science Foundation of China Chinese Mechanical Engineering Society Chinese Association of Automation Life Electronics Society, Chinese Institute of Electronics IEEE ICMA 2015 PROCEEDINGS Additional copies may be ordered from: IEEE Service Center 445 Hoes Lane Piscataway, NJ 08854 U.S.A. IEEE Catalog Number: CFP15839-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4799-7097-1 IEEE Catalog Number (CD-ROM): CFP15839-CDR ISBN (CD-ROM): 978-1-4799-7096-4 Copyright and Reprint Permission: Copyright and Reprint Permission: Abstracting is permitted with credit to the source. Libraries are permitted to photocopy beyond the limit of U.S. copyright law for private use of patrons those articles in this volume that carry a code at the bottom of the first page, provided the per-copy fee indicated in the code is paid through Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923. -

Insights Huining on the Liaison Office

The intriguing appointment of Luo Insights Huining on the Liaison Office In late December 2019, Luo Huining 骆惠宁 was set aside and taken down from his provincial position (Shanxi Party Secretary [2016-2019]) and instead sent, as several 65-year-old Cadres often do before their official retirement, to a commission led by the National People’s Congress (NPC). Luo, a provincial veteran (Anhui Standing Committee [1999-2003], Governor [2010-2013] and Party Secretary of Qinghai [2013-2016]), seemed then to follow in the footsteps of his Qinghai predecessor, Qiang Wei 强卫1. Replaced by Lou Yangsheng 楼阳生 – part of Xi’s Zhejiang “army”, Luo, despite being regarded as competent when it came to the anti-corruption campaign, has never shown any overt signs of siding with Xi. As such, the sudden removal of Wang Zhimin 王志民2 – now ex-director of the Hong Kong Liaison Office for the Central government, which, to be fair, was predictable3, became even more confusing when it became known that he would be replaced by Luo. Some are saying this “new” player could bring a breath of fresh air and bring new perspectives on the current state of affairs; some might see this move as either an ill-advised decision or the result of lengthy negotiations at the top – negotiations that might not have tilted in Xi’s favor. A fall from “grace” in the shadow of Zeng Qinghong Wang Zhimin’s removal, as previously stated, is almost a non-event, as Xi was (and still is) clearly dissatisfied with the way the Hong Kong - Macau affairs system 港澳系统 is dealing with the protests. -

Atrocities in China

ATROCITIES IN CHINA: LIST OF VICTIMS IN THE PERSECUTION OF FALUN GONG IN CHINA Jointly Compiled By World Organization to Investigate the Persecution of Falun Gong PO Box 365506 Hyde Park, MA 02136 Contact: John Jaw - President Tel: 781-710-4515 Fax: 781-862-0833 Web Site: http://www.upholdjustice.org Email: [email protected] Fa Wang Hui Hui – Database system dedicated to collecting information on the persecution of Falun Gong Web Site: http://www.fawanghuihui.org Email: [email protected] April 2004 Preface We have compiled this list of victims who were persecuted for their belief to appeal to the people of the world. We particularly appeal to the international communities and request investigation of this systematic, ongoing, egregious violation of human rights committed by the Government of the People’s Republic of China against Falun Gong. Falun Gong, also called Falun Dafa, is a traditional Chinese spiritual practice that includes exercise and meditation. Its principles are based on the values of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance. The practice began in China in 1992 and quickly spread throughout China and then beyond. By the end of 1998, by the Chinese government's own estimate, there were 70 - 100 million people in China who had taken up the practice, outnumbering Communist Party member. Despite the fact that it was good for the people and for the stability of the country, former President JIANG Zemin launched in July 1999 an unprecedented persecution of Faun Gong out of fears of losing control. Today the persecution of Falun Gong still continues in China. As of the end of March 2004, 918 Falun Gong practitioners have been confirmed to die from persecution. -

China's New Social Governance

China’s New Social Governance Ketty A. Loeb A dissertation Submitted in partial fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: David Bachman, Chair Tony Gill Karen Litfin Mary Kay Gugerty Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Political Science © Copyright 2014 Ketty A. Loeb University of Washington Abstract China’s New Social Governance Ketty A. Loeb Chair of Supervisory Committee: Professor David Bachman Jackson School of International Studies This dissertation explores the sources and mechanisms of social policy change in China during the reform era. In it, I first argue that, starting in the late 1990s, China’s leadership began shifting social policy away from the neoliberal approach that characterized the first two decades of the reform era towards a New Governance approach. Second, I ask the question why this policy transformation is taking place. I employ a political economy argument to answer this question, which locates the source of China’s New Governance transition in diversifying societal demand for public goods provision. China’s leadership is concerned about the destabilizing impacts of this social transformation, and has embraced the decentralized tools of New Governance in order to improve responsiveness and short up its own legitimacy. Third, I address how China’s leadership is undertaking this policy shift. I argue that China’s version of New Governance is being undertaken in such as way as to protect the Chinese Communist Party’s monopoly over power. This double-edged strategy is aimed at improving the capacity consists of Social Construction, on the one hand, and Social Management Innovation, on the other. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual Report 2012

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2012 ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2012 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov 2012 ANNUAL REPORT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2012 ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2012 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 76–190 PDF WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, SHERROD BROWN, Ohio, Cochairman Chairman MAX BAUCUS, Montana FRANK WOLF, Virginia CARL LEVIN, Michigan DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California EDWARD R. ROYCE, California JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota SUSAN COLLINS, Maine MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio JAMES RISCH, Idaho MICHAEL M. HONDA, California EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS SETH D. HARRIS, Department of Labor MARIA OTERO, Department of State FRANCISCO J. SANCHEZ, Department of Commerce KURT M. CAMPBELL, Department of State NISHA DESAI BISWAL, U.S. Agency for International Development PAUL B. PROTIC, Staff Director LAWRENCE T. LIU, Deputy Staff