The British Labour Movement and the End of Empire in Guiana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY RESOLUTION NO. 54 WHEREAS President

• NINTH PARLIAMENT OF GUYNA FIRST SESSION (2006-2008) NATIONAL ASSEMBLY RESOLUTION NO. 54 WHEREAS President Bharrat Jagdeo met on February 19 and 20 with a broad cross-section of representatives from the religious community, business sector, the labour io movement, women, Amerindian, and other civil society bodies to discuss the recent escalation of crime, and from that engagement a joint statement was issued which called for: "1. Commit their full and unqualified support of the joint services in confronting crime in our country and in securing the safety of our citizens under the law, and; 2. Work in collaboration with the Government and all of the parliamentary political parties to jointly review the national security plan for its urgent and comprehensive implementation with the ultimate goal of cementing inclusive democracy, peace and justice in our country; 3. Initiate and support confidence building measures in the society at large 4. and amongst communities and organizations, in order to continue to move the country forward; 4. Call on all political parties to seek in good faith a unified position on law and order and public safety." (A copy attached at Appendix A); /...2 AND WHEREAS President Jagdeo also met on February 19 with the leaders of the five parliamentary political parties to discuss the current crime situation, and following that meeting a joint statement was issued calling for: "1. Unequivocally condemn crime in all its forms especially the recent Lusignan and Bartica massacres; 2. Commit to work together in support of the Joint Services as they fight crime professionally and within the confines of the law; 3. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

At the Polling Place

Date Printed: 04/20/2009 JTS Box Number: IFES 64 Tab Number: 44 Document Title: Guyana Elections Commission Vote '97 Enhancing the Electoral System Document Date: 1997 Document Country: Guyana Document Language: English IFES ID: CE00763 ~IIII~ II~I ~ ~I~ II~ III ~II *~II C - 4 4 6 8 - A Ace - O~EM~~ 7)~/P-t>~ 7)~ 1. Tda /1.(J~ V,c~ It) (!-ti~ d mMArT,' ~ de eu(JmJ~N. 91T.,,,,,, Steg"u /?q",mfaAMI( 7k 1997 &f«Uo •• wat k __ '" de ...- ~ ... de ~ '" U«iep.".ted "",,,,,,,. 7k ••teeu- '" de ~~~ P, ......"e euut '" de 7tce;.",,( .40•• ..,/(" wat _ ""'" k I- de •• ".,."u,. '" de 20d e--r,. 1U1f<> -. eleee wat "'- Iwu; u. de 21~ e--r,. 7k &!eeu.... " ~ de e."Wr.~ euut ~ '" 21~ ~ '1','-' 71# 5 'ff(emelle u- -I.e '" 4-Hl4U ~f"'AtlueltHl sI-de ~ ErlxMr4w & 9,*-_«'"" Uwr at de (!.e1ll1ltt4#"ff t6 MIp tpI#_ pcoU#,.,," .~_ •.e, ... de ,........ '1 ~ '-fu da.e ie ____ '1""e;.". tpI# ...... "'- ~- Ifoiu. SPECIMEN ONLY ~ euut ~- tpI# ..ed t:<> _. • The Voter ID Card is the property of the Elections C-ommisslon • Keep Your Voter ID Card in a safe place until Polling Day -• On Elections Day you will have to return yout Voter ID Card , GENERAL ELECTIONS A.F.G 2.~ T-eTk P-e~ Pb..a 1 ALLIANCE FOR GUYANA ~. WPAlGLP/CITIZENS I~ ~ -e""..'1"~ W >t+ A G.G.G , 2 A GOOD AND GREEN" GUYANA .... 3 G.B.G I~ d" 3. Ma~~X GOD BLEss GUYANA """- F' 4 G.D.P. -- GUYANA l§Sti NU ~ 1te, P~ J.F.A.P 5 JUSTICE FOR ALL PARTY I~I~ ~>W). -

Report of the Commission of Inquiry Appointed to Inquire And

REPORT OF THE COMMISSION OF INQUIRY APPOINTED TO ENQUIRE AND REPORT ON THE CIRCUMSTANCES SURROUNDING THE DEATH IN AN EXPLOSION OF THE LATE DR. WALTER RODNEY ON THIRTEENTH DAY OF JUNE, ONE THOUSAND NINE HUNDRED AND EIGHTY AT GEORETOWN VOLUME 1: REPORT AND APPENDICES FEBRUARY 2016 Transmittal Letter Chapter 6 Contents Chapter 7 Table of Contents Chapter 8 Chapter 1 Chapter 9 Chapter 2 Tendered Exhibits Chapter 3 Procedural Rules Chapter 4 Correspondence Chapter 5 Editorial Note 1 2 Transmittal of Report of the Commission of Inquiry to enquire into and report on the circumstances surrounding the death in an explosion of the late Dr. Walter Rodney on the thirteenth day of June one thousand nine hundred and eighty at Georgetown To His Excellency David A. Granger President of the Co-operative Republic of Guyana Your Excellency, In my capacity as Chairman of the Walter Rodney Commission of Inquiry, I have the honour to submit the Report of the Inquiry to which the President appointed us by Instrument dated 8th February, 2014. The Commissioners were, in the Instrument of Appointment, expected to submit their Report within ten (10) weeks from the start of the Commission. The Commission started its work on 28th April, 2014. As we understand it, the premise informing the early submission date was that the Commission coming thirty-four (34) years after the death of Dr. Walter Rodney and the events surrounding that event, would, in all probability, be supported by only a few persons volunteering to give evidence and/or having an interest in this matter. -

From Grassroots to the Airwaves Paying for Political Parties And

FROM GRASSROOTS TO THE AIRWAVES: Paying for Political Parties and Campaigns in the Caribbean OAS Inter-American Forum on Political Parties Editors Steven Griner Daniel Zovatto Published by Organization of American States (OAS) International IDEA Washington, D.C. 2005 © Organization of American States (OAS) © International IDEA First Edition, August, 2005 1,000 copies Washinton, D.C. The opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Organization of American States or the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Editors: Steven Griner Daniel Zovatto ISBN 0-8270-7856-4 Layout by: Compudiseño - Guatemala, C.A. Printed by: Impresos Nítidos - Guatemala, C.A. September, 2005. Acknowledgements This publication is the result of a joint effort by the Office for the Promotion of Democracy of the Organization of American States, and by International IDEA under the framework of the Inter-American Forum on Political Parties. The Inter-American Forum on Political Parties was established in 2001 to fulfill the mandates of the Inter-American Democratic Charter and the Summit of the Americas related to the strengthening and modernization of political parties. In both instruments, the Heads of State and Government noted with concern the high cost of elections and called for work to be done in this field. This study attempts to address this concern. The overall objective of this study was to provide a comparative analysis of the 34 member states of the OAS, assessing not only the normative framework of political party and campaign financing, but also how legislation is actually put into practice. -

The Rise and Fall of the Labour League of Youth

University of Huddersfield Repository Webb, Michelle The rise and fall of the Labour league of youth Original Citation Webb, Michelle (2007) The rise and fall of the Labour league of youth. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/761/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ THE RISE AND FALL OF THE LABOUR LEAGUE OF YOUTH Michelle Webb A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield July 2007 The Rise and Fall of the Labour League of Youth Abstract This thesis charts the rise and fall of the Labour Party’s first and most enduring youth organisation, the Labour League of Youth. -

Amalgamated Union of Foundry Workers

ID Heading Subject Organisation Person Industry Country Date Location 74 JIM GARDNER (null) AMALGAMATED UNION OF FOUNDRY WORKERS JIM GARDNER (null) (null) 1954-1955 1/074 303 TRADE UNIONS TRADE UNIONS TRADES UNION CONGRESS (null) (null) (null) 1958-1959 5/303 360 ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS NON MANUAL WORKERS ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS (null) (null) (null) 1942-1966 7/360 361 ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS NOW ASSOCIATIONON MANUAL WORKERS ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS N(null) (null) (null) 1967 TO 7/361 362 ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS CONFERENCES NONON MANUAL WORKERS ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS N(null) (null) (null) 1955-1966 7/362 363 ASSOCIATION OF TEACHERS IN TECHNICAL INSTITUTIONS APPRENTICES ASSOCIATION OF TEACHERS IN TECHNICAL INSTITUTIONS (null) EDUCATION (null) 1964 7/363 364 BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) ENTERTAINMENT (null) 1929-1935 7/364 365 BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) ENTERTAINMENT (null) 1935-1962 7/365 366 BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) ENTERTAINMENT (null) 1963-1970 7/366 367 BRITISH AIR LINE PILOTS ASSOCIATION (null) BRITISH AIR LINE PILOTS ASSOCIATION (null) TRANSPORT CIVIL AVIATION (null) 1969-1970 7/367 368 CHEMICAL WORKERS UNION CONFERENCES INCOMES POLICY RADIATION HAZARD -

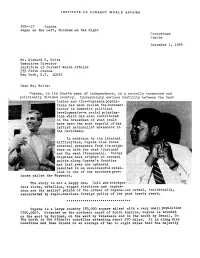

Guyana. Jagan on Left, Burnham on the Right

INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS FJM--17 Guyana Jagan on the Left, Burnham on the Right Georgetown Guyana November l, 1969 Mr, Richard H. NoSte Executive Director l:nstitute of Current World Affairs 535 Fifth Avenue New York, N.Y. lOO17 Dear Mr. Nolte: Guyana., in its fourth year of independence, is a racially tormented and politically divided country. Increasingly serious hostility between the East Indian and Afro-Guyanese popula- tions has made racism the dominant factor in domestic political developments-a racial polariza- tion which has also contributed to the breakdown of what could have been the most hopeful of the leftist nationalist movements in the Caribbean. In addition to its internal difficulties, Guyana also faces external pressures from its neigh- bors on both the east (Surinam) and the west (Venezuela). Border disputes have erupted at several points along Guyana' s frontier and last year one upheavsl resulted in an unsuccessful rebel- lion in one of the southern prov- inces called the Rupununi. The story is not a happy one. Cold war intrigue race riots, rebellion, rigged elections and repres- sion are the sal.ient points of the ordeal of Guyana--an ordeal, incidentally, exacerbated by Anglo-American foreign policy of the past twenty years. Guyana is a large country (83,000 square m+/-le.s) with a very small population (700,000). Situated on the northern coast of South America, Guyana is bounded on the east by Surinam, on the west,by Venezuela and in the south by Brazil. To the north is the Atlantic coastline extending about 270 miles. -

BRADWELL LODGE (Formerly the Rectory) BRADWELL on SEA

MALDON DISTRICT COUNCIL BRADWELL LODGE (formerly the Rectory) BRADWELL ON SEA TM 004 067 Originally a C16 house on a moated site, considerably extended by John Johnson, architect, with the gardens laid out by the agricultural improver and rector (Rev. Sir Henry Bate Dudley) in the late C18. HISTORIC DEVELOPMENT The north wing of Bradwell Lodge was originally a moated Tudor house dating from 1520. It was believed to have been given to Ann of Cleeves by Henry VIII as part of the divorce settlement. The Rev. Sir Henry Bate Dudley (1745-1824) purchased the advowson of Bradwell-juxta-Mare in 1781 for a reported sum of £1,500. He acted as curate for the absentee rector George Pawson until 1797 and leased the neglected glebe from him. Writing to the bishop in March 1798, Bate Dudley explained how when he had arrived at Bradwell the glebe of 300 acres was in so ruinous a state from flooding and neglect that no one would farm it. Bate Dudley drained the glebe and the first mark of recognition of what he had done came from the Society of Arts in 1788 when he was granted the Silver Medal for reclaiming the land from the sea. In his report to the Society, Bate Dudley said that he had enclosed 45 acres by September 1786 and by 1800, when he was awarded the Gold Medal, he had reclaimed 206 acres and was growing corn on the land. He spent £28,000 of his personal fortune in draining the marshland round Bradwell and eventually reclaimed over 250 acres of marshland and applied mole drainage to heavy land. -

What Do Yeats and the Citadel Have in Common?

Against the Grain Volume 28 | Issue 5 Article 33 2016 Bet You Missed It--What Do Yeats and The itC adel Have in Common? Bruce Strauch The Citadel, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/atg Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Strauch, Bruce (2016) "Bet You Missed It--What Do Yeats and The itC adel Have in Common?," Against the Grain: Vol. 28: Iss. 5, Article 33. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.7530 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Bet You Missed It Press Clippings — In the News — Carefully Selected by Your Crack Staff of News Sleuths Column Editor: Bruce Strauch (The Citadel) Editor’s Note: Hey, are y’all reading this? If you know of an article that should be called to Against the Grain’s attention ... send an email to <[email protected]>. We’re listening! — KS ENDURING QUOTABILITY BOOK DEFICIT GUILT by Bruce Strauch (The Citadel) by Bruce Strauch (The Citadel) In 1919, Yeats wrote his chilling poem “The Second Coming.” And Of course no one’s actually read Ulysses. It just sits on the shelf. yes, you know it because someone is constantly quoting from it. “And what But you feel bad about it. What to do? rought beast, its hour come round at last, Slouches towards Bethelehem to Curtis Sittenfeld wrote the 2016 best-selling Eligible — a retell- be born?” “The centre cannot hold.” “Things fall apart.” “The best lack ing of Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. -

A 'Special Relationship'?

A ‘special relationship’? prelims.p65 1 08/06/2004, 14:37 To Karin prelims.p65 2 08/06/2004, 14:37 A ‘special relationship’? Harold Wilson, Lyndon B. Johnson and Anglo- American relations ‘at the summit’, 1964–68 Jonathan Colman Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave prelims.p65 3 08/06/2004, 14:37 Copyright © Jonathan Colman 2004 The right of Jonathan Colman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 7010 4 hardback EAN 978 0 7190 7010 5 First published 2004 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset by Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall www.freelancepublishingservices.co.uk Printed in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, King’s Lynn prelims.p65 4 08/06/2004, 14:37 Contents Acknowledgements page vi Abbreviations vii Introduction 1 1 The approach to the summit 20 2 The Washington summit, 7–9 December 1964 37 3 From discord to cordiality, January–April 1965 53 4 ‘A battalion would be worth a billion’? May–December 1965 75 5 Dissociation, January–July 1966 100 6 A declining relationship, August 1966–September 1967 121 7 One ally among many, October 1967–December 1968 147 Conclusion: Harold Wilson and Lyndon B. -

L'evoluzione Dei Sindacati Europei

3 Europa 03_03 Cruciani_IstitutoEuropa 03/10/18 12:23 Pagina 154 3 Europa 03-03 Cruciani - definitivo Sante Cruciani L’evoluzione dei sindacati europei I sindacati nella dinamica europea con il concorso dell’AFL (American Federation of Labor) alla Conferenza di Zurigo del 10-16 settembre L’attuale dibattito politico e storiografico sulla crisi 1913. Dopo l’identificazione dei sindacati europei con dell’Unione Europea (UE), la rinascita dei naziona- i governi di ‘unione sacra’ prodotti dalla Grande guer - lismi e l’arduo rilancio del processo di integrazione ra, la rivoluzione sovietica del 1917, la formazione devono confrontarsi con la società civile e il ruolo dei della Confederazione internazionale dei sindacati cri- sindacati nello spazio sociale europeo. stiani (CISC) nel 1920 e dell’Internazionale sindacale All’indomani del Trattato di Maastricht del 7 feb- rossa (ISR) nel 1921 attestarono il progressivo inde- braio 1992, gli storici hanno posto l’attenzione sui sin- bolimento della FSI (Maiello 2002). dacati e sulle organizzazioni transnazionali dei lavo- Negli anni Venti e Trenta del Novecento, le espe- ratori quali attori della costruzione europea, rimarcando rienze dei sindacati europei possono essere racchiuse il loro contributo a un’‘altra via per l’Europa’ (L’al- nel riformismo del TUC, nel ‘corporativismo plura- tra via per l’Europa, 1999), più sensibile al rafforza- lista’ della Repubblica di Weimar, nel ‘corporativi- mento del modello sociale europeo nel mondo della smo autoritario’ dell’Italia fascista, nella ricomposi-