Neocubism and Italian Painting Circa 1949: an Avant-Garde That Maybe Wasn’T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pages 4 Rotella, Lot 51 Pagine

LOT 42 In copertina | Cover Pagine 4 | Pages 4 Pagina 133 | Page 133 Baechler, lot 15 Rotella, lot 51 Turcato, lot 29 Retro copertina | Back cover Pagine 6-7 | Pages 6-7 Pagina 142 | Page 142 Arman, lot 25 Schifano, lot 30 Melotti, lot 33 Pagina 1 | Page 1 Pagine 8-9 | Pages 8-9 Pagina 143 | Page 143 Dorazio, lot 42 Music, lot 60 Cassinari, lot 39 SEDE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18, 20123 MILANO ASTA ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA 10 NOVEMBRE 2020 MILANO, VIA SACCHI 7 – presso LA POSTERIA 23 OTTOBRE - 4 NOVEMBRE, MILANO VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 0 (ORARIO 10.00-19.00 – ESCLUSO FESTIVI E 29 OTTOBRE) PREVIO APPUNTAMENTO 7-8-9 NOVEMBRE, MILANO, VIA SACCHI 7 (ORARIO 10.00-19.00) UNICA SESSIONE MARTEDÌ 10 NOVEMBRE 2020 ORE 16.00 LOTTI 1 - 243 PRESENTAZIONE TELEVISIVA TOP LOTS Lunedì 2/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Martedì 3/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Giovedì 5/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Venerdì 6/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre OFFERTE SCRITTE FINO A LUNEDÌ 9 NOVEMBRE 2020 ORE 15.00 FAX +39 02 40703717 [email protected] È possibile partecipare in diretta on-line inscrivendosi (almeno 24 ore prima) sul nostro sito www.ambrosianacasadaste.com CONSULTAZIONE CATALOGO E MODULISTICA www.ambrosianacasadaste.com da venerdì 23 ottobre 2020 AMBROSIANA CASA D’ASTE / GALLERIA POLESCHI CASA D’ASTE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 20123 MILANO - TEL. +39 0289459708 - FAX +39 0240703717 www.ambrosianacasadaste.com • [email protected] LOT 51 338 1226703 5 MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY ART -

Copertina Artepd.Cdr

Trent’anni di chiavi di lettura Siamo arrivati ai trent’anni, quindi siamo in quell’età in cui ci sentiamo maturi senza esserlo del tutto e abbiamo tantissime energie da spendere per il futuro. Sono energie positive, che vengono dal sostegno e dal riconoscimento che il cammino fin qui percorso per far crescere ArtePadova da quella piccola edizio- ne inaugurale del 1990, ci sta portando nella giusta direzione. Siamo qui a rap- presentare in campo nazionale, al meglio per le nostre forze, un settore difficile per il quale non è ammessa l’improvvisazione, ma serve la politica dei piccoli passi; siamo qui a dimostrare con i dati di questa edizione del 2019, che siamo stati seguiti con apprezzamento da un numero crescente di galleristi, di artisti, di appassionati cultori dell’arte. E possiamo anche dire, con un po’ di vanto, che negli anni abbiamo dato il nostro contributo di conoscenza per diffondere tra giovani e meno giovani l’amore per l’arte moderna: a volte snobbata, a volte non compresa, ma sempre motivo di dibattito e di curiosità. Un tentativo questo che da qualche tempo stiamo incentivando con l’apertura ai giovani artisti pro- ponendo anche un’arte accessibile a tutte le tasche: tanto che nei nostri spazi figurano, democraticamente fianco a fianco, opere da decine di migliaia di euro di valore ed altre che si fermano a poche centinaia di euro. Se abbiamo attraversato indenni il confine tra due secoli con le sue crisi, è per- ché l’arte è sì bene rifugio, ma sostanzialmente rappresenta il bello, dimostra che l’uomo è capace di grandi azzardi e di mettersi sempre in gioco sperimen- tando forme nuove di espressione; l’arte è tecnica e insieme fantasia, ovvero un connubio unico e per questo quasi magico tra terra e cielo. -

Redalyc.Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: from Pittura

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas ISSN: 0185-1276 [email protected] Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas México AGUIRRE, MARIANA Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917- 1928 Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, vol. XXXV, núm. 102, 2013, pp. 93-124 Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36928274005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative MARIANA AGUIRRE laboratorio sensorial, guadalajara Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917-1928 lthough the art of the Bolognese painter Giorgio Morandi has been showcased in several recent museum exhibitions, impor- tant portions of his trajectory have yet to be analyzed in depth.1 The factA that Morandi’s work has failed to elicit more responses from art historians is the result of the marginalization of modern Italian art from the history of mod- ernism given its reliance on tradition and closeness to Fascism. More impor- tantly, the artist himself favored a formalist interpretation since the late 1930s, which has all but precluded historical approaches to his work except for a few notable exceptions.2 The critic Cesare Brandi, who inaugurated the formalist discourse on Morandi, wrote in 1939 that “nothing is less abstract, less uproot- ed from the world, less indifferent to pain, less deaf to joy than this painting, which apparently retreats to the margins of life and interests itself, withdrawn, in dusty kitchen cupboards.”3 In order to further remove Morandi from the 1. -

And Variations – Post-Wa Art from The

Palazzo Venier dei Leoni 701 Dorsoduro 30123 Venezia, Italy Telephone 041 2405 411 Telefax 041 5206885 Press release THEMES AND VARIATIONS POST-WAR ART FROM THE GUGGENHEIM COLLECTIONS February 2 – August 4, 2002 On Friday 1st February 2002, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, will inaugurate Themes and Variations – Post-war Art from the Guggenheim Collections. Curated by Luca Massimo Barbero, this 6-month cycle of installations will assemble paintings, sculptures and works on paper - both European and American, but predominantly Italian – from the holdings of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, with a small number of additional private loans. This dynamic and innovative project sets out to provide a fuller understanding and contextualization of the post-war works in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. A series of three two-month installations – examining in turn a succession of movements and artists with which Peggy Guggenheim was affiliated first in New York and later Venice - will present works by a strong group of post-war 20th century artists, including Edmondo Bacci, Francis Bacon, César, Joseph Cornell, Jean Dubuffet, Marcel Duchamp, Alberto Giacometti, Asger Jorn, Bice Lazzari, René Magritte, Henry Moore, Ben Nicholson, Mimmo Rotella, Giuseppe Santomaso, Tancredi, Laurence Vail, Victor Vasarely and Emilio Vedova. Themes and Variations provides an opportunity to present for the first time recent acquisitions of post-war art, including important works by Carla Accardi, Agostino Bonalumi, Costantino Nivola, Mimmo Rotella and Toti Scialoja, alongside previously acquired works by Edmondo Bacci, Lucio Fontana, Conrad Marca-Relli, Giuseppe Santomaso and Armando Pizzinato. A series of private loans will further strengthen the representation of Italian post-war art; it is in this context that the work of Mirko Basaldella will be presented in depth in the course of the initial February- March installation. -

Cézanne and the Modern: Masterpieces of European Art from the Pearlman Collection

Cézanne and the Modern: Masterpieces of European Art from the Pearlman Collection Paul Cézanne Mont Sainte-Victoire, c. 1904–06 (La Montagne Sainte-Victoire) oil on canvas Collection of the Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation, on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum TEACHER’S STUDY GUIDE WINTER 2015 Contents Program Information and Goals .................................................................................................................. 3 Background to the Exhibition Cézanne and the Modern ........................................................................... 4 Preparing Your Students: Nudes in Art ....................................................................................................... 5 Artists’ Background ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Modern European Art Movements .............................................................................................................. 8 Pre- and Post-Visit Activities 1. About the Artists ....................................................................................................................... 9 Artist Information Sheet ........................................................................................................ 10 Modern European Art Movements Fact Sheet .................................................................... 12 Student Worksheet ............................................................................................................... -

W E L C O M E T O B O C C O

International Relations WELCOME TO BOCCONI Life at Bocconi Luigi Bocconi Università Commerciale WELCOME TO BOCCONI PART II: LIFE AT BOCCONI WELCOME TO BOCCONI Life at Bocconi INTRODUCTION ______________________________________________________5 Bocconi University Internationalisation in figures Bocconi International perspective Academic Information Glossary for Students LIVING IN BOCCONI ISD ____________________________________________________________________________8 International Student Desk Welcome Desk Buddy Service University Tour Bocconi Welcome Kit Day Trips Italian Language Course What's on in Milan Cocktail for International Students HOUSING ______________________________________________________________________9 How can I pay my rent? How can I have my deposit back? USEFUL INFORMATION ________________________________________________________10 ID Card Punto Blu, Virtual Punto Blu and Internet points Certificates Bocconi E-mail and yoU@B Official Communications Meals Computer Rooms Access the Bocconi Computer Network with your own laptop Mailboxes Bookstore ACADEMIC INFORMATION ______________________________________________________15 Study Plan Exams Transcript - Only for Exchange Students SERVICES ____________________________________________________________________19 International Recruitment Service Library Language Centre ISU Bocconi (Student Assistance and Financial Aid) Working in Italy and abroad CESDIA SCHOLARSHIPS AND LOANS __________________________________________________20 ANNEX 1: Exchange Students __________________________________________________21 -

Modigliani's Recipe: Sex, Drugs and Long, Long Necks

The New York Times, August 3, 2003 Modigliani's Recipe: Sex, Drugs and Long, Long Necks By PETER PLAGENS VINCENT VAN GOGH had a 10-year working life that can hardly be called a "career," and yet he's just about the biggest draw ever in museum exhibitions, at least per square inch of canvas covered. When the 1998 "Van Gogh's van Goghs" exhibition entered the home stretch of its run at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, officials had to keep the place open 24 hours a day on the last weekend to accommodate the crowds. Amedeo Modigliani O.K., that's van Gogh. But since June 26, visitors have been streaming into the same museum at the rate of more than 1,400 a day (which a spokesperson calls "astounding" for them) to see the work of a different painter with an equally brief working life. The attraction, which originated at the Albright-Knox Gallery in Buffalo (where the museum had to turn away visitors during the last two weeks) and then stopped at the Kimbell Museum in Fort Worth, is an exhibition called "Modigliani and the Artists of Montparnasse." (It runs through Sept. 28.) Although the show includes healthy doses of Chagall, Soutine and Rivera (among others), the benighted Amedeo Modigliani (1884- 1920) is the real draw. What is it about this artist, who painted deceptively simple, semi-abstracted, sloe-eyed women over and over again, that pleases the public so much? It could be at least partly the biography. Modigliani was born an outsider — his parents were Sephardic Jews in Livorno, Italy — and grew up sickly and tubercular. -

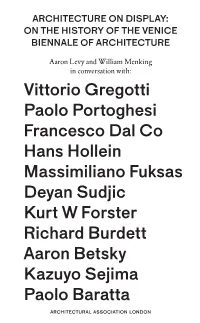

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

The Museum of Modern Art 11 West 53 Street, New York 19, N

LOCAL ORANGE THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 11 WEST 53 STREET, NEW YORK 19, N. Y. TELEPHONE CIRCLE 5-8900 5lOl|05 - 22 FOR WEDNESDAY RELEASE EXHIBITION OP LIFE WORK OF MODIGLIANI, ITALIAN PAINTER AND SCULPTOR, TO GO ON VIEW Fifty-two oils, 7 sculptures and h£ drawings, watercolors and pastels by the well-known Italian artist Amedeo Modigliani (l88lj.-1920) will occupy the third floor galleries of the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, from April 11 through June 10, Organized in collaboration with The Cleveland Museum of Art, where it has just concluded its showing,, the exhibition has been brought together from collections in Paris and Milan, England and Brazil, and many parts of this country. Among the foreign loans is a large group of early works never exhibited before outside of France, The exhibition was organized by the Depart ment of Painting and Sculpture and installed by Margaret Miller, Associate Curator of the Department, The catalog contains an appreciative essay on the artist by James thrall Soby, the well-known art writer and expert on modern Italian art; lj2 plates, 2 in color; a check-list and bibliography. Biographical Notes: Modigliani was born in Leghorn, Italy, on July 12, I88I4., the youngest of k children of a banker of Jewish origin. He died in Paris at the age of only 35• Following a sickly childhood and an interrupted schooling, he developed tuberculosis at the age of l6 and was taken by his mother to an art school in Rome. In 1906 he went to Paris, where his work was at first influenced by the style of the 1890a, He was soon to come under the spell of Picasso and Ce'zanne. -

Sito STORIA2 RS INGLESE REVISED

You may download and print this text by Roberta Serpolli, solely for personal use THE PANZA COLLECTION STORY “The Panza Collection is entirely a couple’s affair. When my wife Giovanna and I discover works by a new artist, I look at her and she looks at me. I can see in her eyes if she wants to buy or not. So even between my wife and me, ‘looking’ is an issue.” Giuseppe Panza, 20091 Giuseppe Panza di Biumo, along with his wife Giovanna, is recognized as one of the world’s foremost collectors of contemporary art. The collection, originally composed of around 2,500 works of art, is mainly representative of the most significant developments in American art from post- World War II to the 21st century. Along with a need to fulfill spiritual and inner quests, both intuition and reflection have inspired the collectors’ choice that would demonstrate, retrospectively, their far- sightedness. By devoting themselves to an in-depth focus on emerging artists and specific creative periods, the Panzas contributed to acknowledging the new art forms among both the general public and the art market. The Beginnings of the Collection: On the Road to America The collection ideally began in 1954 when Giuseppe, at the age of thirty years, traveled to South America and the United States, from New York to Los Angeles, where he discovered the continents’ captivating vitality of economy and culture. Upon his return to Milan, he felt the need to take part in the international cultural milieu. In 1955, shortly after his marriage with Giovanna Magnifico, Giuseppe purchased his first work of art by Italian abstract painter Atanasio Soldati. -

Giuseppe Bartolini: Il Linguaggio Fotografico Nella Sua Opera

UNIVERSITÀ DI PISA Dipartimento di Civiltà e Forme del Sapere Corso di Laurea in Scienze dei Beni Culturali Giuseppe Bartolini Il linguaggio fotografico nella sua opera Candidato: Francesca Paoli Relatore: Prof. Sergio Cortesini Anno accademico 2017/2018 Indice Introduzione ................................................................................................................. 1 Cap. 1 GIUSEPPE BARTOLINI .................................................................................. 4 1.1 Gli inizi ............................................................................................................... 4 1.2 La fase “memoriale” .......................................................................................... 18 1.3 Dalla svolta degli anni Settanta ai Duemila ........................................................ 30 1.4 La parentesi della “Metacosa” ........................................................................... 36 1.5 L’ultimo periodo ............................................................................................... 39 Cap. 2 PITTURA E FOTOGRAFIA .......................................................................... 42 2.1 Il linguaggio fotografico nell’opera di Bartolini ................................................. 42 2.2 Giuseppe Bartolini e Luigi Ghirri ...................................................................... 50 Conclusioni ................................................................................................................ 60 Bibliografia ............................................................................................................... -

CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale Di Venezia La Biennale Di Venezia President Presents Roberto Cicutto

LE MUSE INQUIETE WHEN LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA MEETS HISTORY CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale di Venezia La Biennale di Venezia President presents Roberto Cicutto Board The Disquieted Muses. Luigi Brugnaro Vicepresidente When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History Claudia Ferrazzi Luca Zaia Auditors’ Committee Jair Lorenco Presidente Stefania Bortoletti Anna Maria Como in collaboration with Director General Istituto Luce-Cinecittà e Rai Teche Andrea Del Mercato and with AAMOD-Fondazione Archivio Audiovisivo del Movimento Operaio e Democratico Archivio Centrale dello Stato Archivio Ugo Mulas Bianconero Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche Fondazione Modena Arti Visive Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea IVESER Istituto Veneziano per la Storia della Resistenza e della Società Contemporanea LIMA Amsterdam Peggy Guggenheim Collection Tate Modern THE DISQUIETED MUSES… The title of the exhibition The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History does not just convey the content that visitors to the Central Pavilion in the Giardini della Biennale will encounter, but also a vision. Disquiet serves as a driving force behind research, which requires dialogue to verify its theories and needs history to absorb knowledge. This is what La Biennale does and will continue to do as it seeks to reinforce a methodology that creates even stronger bonds between its own disciplines. There are six Muses at the Biennale: Art, Architecture, Cinema, Theatre, Music and Dance, given a voice through the great events that fill Venice and the world every year. There are the places that serve as venues for all of La Biennale’s activities: the Giardini, the Arsenale, the Palazzo del Cinema and other cinemas on the Lido, the theatres, the city of Venice itself.