The Vintner's Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BUBBLES PINOT NOIR-CHARDONNAY, Pierre

Wines By The Glass BUBBLES PINOT NOIR-CHARDONNAY, Pierre Paillard, ‘Les Parcelles,’ Bouzy, Grand Cru, 25 Montagne de Reims, Extra Brut NV -treat yourself to this fizzy delight MACABEO-XARELLO-PARELLADA, Mestres, 'Coquet,' Gran Reserva, 14 Cava, Spain, Brut Nature 2013 -a century of winemaking prowess in every patiently aged bottle ROSÉ OF PINOT NOIR, Val de Mer, France, Brut Nature NV 15 -Piuze brings his signature vibrant acidity to this juicy berried fizz WHITE + ORANGE TOCAI FRIULANO, Mitja Sirk, Venezia Giulia, Friuli, Italy ‘18 14 -he made his first wine at 11; now he just makes one wine-- very well, we think FRIULANO-RIBOLLA GIALLA-chardonnay, Massican, ‘Annia,’ 17 Napa Valley, CA USA ‘17 -from the heart of American wine country, an homage to Northern Italy’s great whites CHENIN BLANC, Château Pierre Bise, ‘Roche aux Moines,’ 16 Savennières, Loire, France ‘15 -nerd juice for everyone! CHARDONNAY, Enfield Wine Co., 'Rorick Heritage,' 16 Sierra Foothills, CA, USA ‘18 -John Lockwood’s single vineyard dose of California sunshine RIESLING, Von Hövel, Feinherb, Saar, Mosel, Germany ‘16 11 -sugar and spice and everything nice TROUSSEAU GRIS, Jolie-Laide, ‘Fanucchi Wood Road,’ Russian River, CA, USA ‘18 15 -skin contact lends its textured, wild beauty to an intoxicating array of fruit 2 Wines By The Glass ¡VIVA ESPAÑA! -vibrant wines sprung from deeply rooted tradition and the passion of a new generation VIURA-MALVASIA-garnacha blanca, Olivier Rivière, ‘La Bastid,’ Rioja, Spain ‘16 16 HONDARRABI ZURI, Itsasmendi, ‘Bat Berri,’ Txakolina -

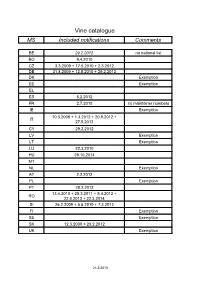

Vine Catalogue MS Included Notifications Comments

Vine catalogue MS Included notifications Comments BE 29.2.2012 no national list BG 9.4.2010 CZ 3.3.2009 + 17.5.2010 + 2.3.2012 DE 31.8.2009 + 12.5.2010 + 29.2.2012 DK Exemption EE Exemption EL ES 8.2.2012 FR 2.7.2010 no maintainer numbers IE Exemption 10.3.2008 + 1.3.2012 + 20.9.2012 + IT 27.5.2013 CY 29.2.2012 LV Exemption LT Exemption LU 22.3.2010 HU 29.10.2014 MT NL Exemption AT 2.2.2012 PL Exemption PT 28.2.2012 13.4.2010 + 25.3.2011 + 5.4.2012 + RO 22.4.2013 + 22.3.2014 SI 26.2.2009 + 5.5.2010 + 7.3.2012 FI Exemption SE Exemption SK 12.3.2009 + 20.2.2012 UK Exemption 21.5.2015 Common catalogue of varieties of vine 1 2 3 4 5 Known synonyms Variety Clone Maintainer Observations in other MS A Abbuoto N. IT 1 B, wine, pas de Abondant B FR matériel certifiable Abouriou B FR B, wine 603, 604 FR B, wine Abrusco N. IT 15 Accent 1 Gm DE 771 N Acolon CZ 1160 N We 725 DE 765 B, table, pas de Admirable de Courtiller B FR matériel certifiable Afuz Ali = Regina Agiorgitiko CY 163 wine, black Aglianico del vulture N. I – VCR 11, I – VCR 14 IT 2 I - Unimi-vitis-AGV VV401, I - Unimi-vitis- IT 33 AGV VV404 I – VCR 7, I – VCR 2, I – Glianica, Glianico, Aglianico N. VCR 13, I – VCR 23, I – IT 2 wine VCR 111, I – VCR 106, I Ellanico, Ellenico – VCR 109, I – VCR 103 I - AV 02, I - AV 05, I - AV 09, I - BN 2.09.014, IT 31 wine I - BN 2.09.025 I - Unimi-vitis-AGT VV411, I - Unimi-vitis- IT 33 wine AGTB VV421 I - Ampelos TEA 22, I - IT 60 wine Ampelos TEA 23 I - CRSA - Regione Puglia D382, I - CRSA - IT 66 wine Regione Puglia D386 Aglianicone N. -

Determining the Classification of Vine Varieties Has Become Difficult to Understand Because of the Large Whereas Article 31

31 . 12 . 81 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 381 / 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION ( EEC) No 3800/81 of 16 December 1981 determining the classification of vine varieties THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Whereas Commission Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/ 70 ( 4), as last amended by Regulation ( EEC) No 591 /80 ( 5), sets out the classification of vine varieties ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas the classification of vine varieties should be substantially altered for a large number of administrative units, on the basis of experience and of studies concerning suitability for cultivation; . Having regard to Council Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 of 5 February 1979 on the common organization of the Whereas the provisions of Regulation ( EEC) market in wine C1), as last amended by Regulation No 2005/70 have been amended several times since its ( EEC) No 3577/81 ( 2), and in particular Article 31 ( 4) thereof, adoption ; whereas the wording of the said Regulation has become difficult to understand because of the large number of amendments ; whereas account must be taken of the consolidation of Regulations ( EEC) No Whereas Article 31 of Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 816/70 ( 6) and ( EEC) No 1388/70 ( 7) in Regulations provides for the classification of vine varieties approved ( EEC) No 337/79 and ( EEC) No 347/79 ; whereas, in for cultivation in the Community ; whereas those vine view of this situation, Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/70 varieties -

Wine Listopens PDF File

Reservations Accepted | 10/1/2021 1 Welcome to Virginia’s First Urban Winery! What’s an Urban Winery, you ask? Well, we are. Take a look around, and you’ll see a pretty unique blend of concepts. First and foremost, you’ll see wine made here under our Mermaid label, highlighting the potential of Virginia’s grapes and wine production. Virginia has a rich history of grape growing and winemaking, and we’ve selected the best grapes we can get our hands on for our Mermaid Wines. We primarily work with fruit from our Charlottesville vineyard, with occasional sourcing from other locations if we see the opportunity to make something special. We’ve put together some really enjoyable wines for you to try – some classic, some fun, all delicious. Secondly, you’ll see wines from all around the world. Some you’ll recognize, others you might not. These selections lend to our wine bar-style atmosphere and really enrich the experience by offering a wide range of wines to be tried. They’re all available by the bottle, and most by the glass and flight as well, right alongside our Mermaid Wines. The staff can tell you all about any of them, so rest assured that you’ll never be drinking blind. These wines also rotate with the season, and there’s always something new to try. We have a full kitchen too, with a diverse menu that can carry you through lunch, brunch and dinner from the lightest snack to a full-on meal. With dishes that can be easily paired with a variety of our wines, make sure you try anything that catches your eye. -

Chardonnay Gewürztraminer Pinot Grigio Riesling

RED MALBEC BARBERA C ate na 43 Mendoza, Argentina ‘18 G.D. Vajra, Barbera d’Alba 43 Terrazas 37 Piedmont, Italy ’17 Mendoza, Argentina ‘17 WHITE La Spinetta, ‘Ca’ Di Pian,’ 54 Barbera d’Asti MERLOT Piedmont, Italy ‘16 CHARDONNAY Duckhorn 60 Napa Valley, CA ‘17 Domaine Drouhin-Vaudon 64 BARBARESCO Burgundy, France ‘19 Markham 52 Michele Chiarlo ‘Reyna’ 65 Napa Valley, CA ‘17 Hartford Court 60 Piedmont, Italy ‘14 Russian River Valley, CA ‘18 Villadoria 60 PETITE SIRAH Landmark, ‘Overlook’ 41 Piedmont, Italy ‘15 J. Lohr, Tower Road 43 Sonoma County, CA ‘18 CABERNET FRANC Paso Robles, CA ‘16 Louis Jadot 50 Burgundy, France ’16 Dr. Konstantin Frank 43 PINOT NOIR Finger Lakes, NY ‘16 Migration 52 B anshe e 38 Russian River Valley, CA ‘16 Michael David, ‘Inkblot’ 59 Sonoma County, CA ‘18 Lodi, CA ‘17 Orin Swift, ‘Mannequin’ 66 Ghost Pines, ‘Winemaker’s Blend’ 40 California ‘16 CABERNET SAUVIGNON & California ‘17 BORDEAUX BLENDS GEWÜ RZTRAMINER Erath, ‘Estate Selection’ 63 BV Estate 57 Willamette Valley, OR ‘16 Gundlach Bundschu 45 Napa Valley, CA ‘16 Nautilus, Southern Valley 68 Sonoma Coast, CA ‘17 C anvas b ac k 51 Marlborough, New Zealand ‘15 Lucien Albrecht 36 Red Mountain, WA ‘16 Purple Hands, ‘Latchkey Vineyard’ 100 Alsace, France ‘17 Caymus 1L 145 Dundee Hills, OR, ‘13 PINOT GRIGIO Napa Valley, CA, ‘19 Talbott, ‘Sleepy Hollow’ 77 Santa Lucia Highlands, CA ‘17 Benton Lane 43 Darioush, ‘Caravan’ 160 Napa Valley, CA, ‘17 Willamette Valley, OR ‘17 TEMPRANILLO Livio Felluga 52 Decoy 45 Muga, Rioja Reserva 62 Sonoma County, CA ‘18 Friuli-Venezia -

• Wine List • by the Glass Champagne & Sparkling

• WINE LIST • BY THE GLASS CHAMPAGNE & SPARKLING Elvio Tintero ‘Sori Gramella’ NV Moscato d’Asti DOCG 46 Piedmont, IT SPARKLING “Sori” means South-facing slope in Piedmontese Zonin Prosecco NV Brut 13 Veneto, IT Zonin NV Brut Prosecco 52 Veneto, IT Prosecco is style of wine as well as a recognized appellation Domaine Chandon ‘étoile’ NV Rosé 23 North Coast, CA Domaine Chandon NV Brut 65 CA Napa Valley’s branch of the famous Champagne house WHITE Enrico Serafino 2013 Brut Alta Langa DOCG 74 Cà Maiol Lugana, Trebbiano 11 Piedmont, IT 2018, Veneto, IT The Serafino winery was founded in 1878 Santa Cristina Pinot Grigio 14 Laurent Perrier ‘La Cuvee’ NV Brut Champagne 90 2017, Tuscany, IT The fresh style is from the high proportion of Chardonnay in the blend Mastroberardino Falanghina del Sannio 16 2017, Campania, IT Moët & Chandon ‘Imperial’ NV Brut Champagne 104 Cakebread Sauvignon Blanc 20 Moët & Chandon Grand Vintage 2012 Brut Champagne 180 2018, Napa Valley, CA Established in 1743 by Claude Moët Flowers Chardonnay 24 Monte Rossa ‘Coupe’ NV Ultra Brut Franciacorta DOCG 110 2016, Sonoma Coast, CA Franciacorta is Italy’s answer to Champagne Veuve Clicquot ‘Yellow Label’ NV Brut Reims, Champagne 132 RED Veuve Clicquot ‘La Grande Dame’ Brut Reims, Champagne 260 Tascante Etna Rosso, Nerello Mascalese 13 2008 This iconic estate is named for the widow who invented ‘remouage’ 2016, Sicily, IT Frederic Savart ‘L’Ouverture’ 150 Tua Rita ‘Rosso Dei Notri’ Sangiovese Blend 16 2016, Tuscany, IT NV Brut Blanc de Noirs 1er Cru Champagne Pra ‘Morandina’, -

Tesi Di Laurea Università Degli Studi Di Milano Facoltà Di

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI MILANO FACOLTÀ DI SCIENZE AGRARIE E ALIMENTARI Corso di Laurea in Valorizzazione e Tutela dell’Ambiente e del Territorio Montano TESI DI LAUREA Valorizzazione di un vitigno autoctono valtellinese: il caso della Brugnola RELATORE Chiarissimo Prof. Lucio Brancadoro CANDIDATO Debora Duico Matr. 782747 ________________________________________ Anno Accademico 2012/2013 Ai miei genitori INDICE pag. Introduzione I 1 Storia della viticoltura valtellinese 1 1.1 Le origini della viticoltura 1 1.2 Le prime vie di diffusione 1 1.3 Gli albori dei siti vitati in Valtellina 3 1.4 Le “malattie” d’Oltreoceano 4 1.5 La documentazione sulle varietà dei vitigni locali 5 1.6 Nascita e sviluppo della tecnica vivaistica 7 1.7 Fase sperimentale per il miglioramento della viticoltura valtellinese 8 1.8 Istituzione dei marchi DOC e DOCG 9 1.9 Il progetto della Fondazione Fojanini di Sondrio 9 2 La Valtellina. Le sue caratteristiche e i suoi vini 11 2.1 Collocazione geografica della Valtellina 11 2.2 La geopedologia 12 2.3 Il clima 13 2.4 L’area vitata 13 2.5 Il paesaggio rurale 15 2.6 I sistemi di coltivazione e i costi economici 16 2.7 La dislocazione delle aziende agricole 16 2.8 I vitigni 17 2.9 Istituzione delle Denominazioni di Origine 19 2.9.1 I DOC 20 2.9.2 I DOCG 20 2.9.3 Gli IGT 22 3 La Brugnola 23 3.1 Introduzione e storia 23 3.2 Caratteristiche ampelografiche 24 3.3 Fenologia 25 3.4 Caratteristiche e attitudini colturali 26 3.5 Superficie di coltivazione 27 3.6 Utilizzo 28 4 Selezione clonale e vinificazioni 29 4.1 La selezione -

There Has Never Been a Better Time to Drink Wine. It Is Being Produced in a Wide Array of Styles, Offering an Unprecedented Level of Fun and Pleasure

There has never been a better time to drink wine. It is being produced in a wide array of styles, offering an unprecedented level of fun and pleasure. Our wine program has been designed to make the most of this. The wine list is organized by flavor profile, varietal, and theme. This allows you to choose how you would like to read it. Skim along the right side of each page to select a wine based on varietal or flavor profile. Alternatively, take some time to read the text on the left hand side of the page and select a wine based on a theme. Finally, we invite you to engage both your server and sommelier in dialogue about the wine list. TABLE OF CONTENTS by flavor profile BUBBLES p. 7 to 13 WHITES Crisp & Clean, Light & Lean p. 13 to 15 Floral, Aromatic, Exotic p. 17 to 27 Full Bodied, Rich & Round p. 29 to 35 REDS Low Grip, High Pleasure p. 37 to 47 Dry, Aromatic, Structured p. 49 to 71 Black & Blue p. 73 to 75 SWEET Sticky and Sweet p. 77 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS by varietal WHITES Alsatian Noble Varietals p. 27 Chardonnay p. 29 to 35 Chenin Blanc p. 13 Grüner Veltliner p. 19 Kerner, Muller-Thurgau, Sylvaner, etc. p. 25 Riesling p. 13 & 27 Sauvignon Blanc p. 15 Fantasy Field Blends p. 23 Friulano p. 17 Malvasia Istriana, Vitovska, Ribolla Gialla p. 21 Macerated Wines p. 21 REDS Rosé & Barbera p. 43 Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot & Cabernet Franc p. 49 to 55 Corvina, Rondinella & Molinara p. -

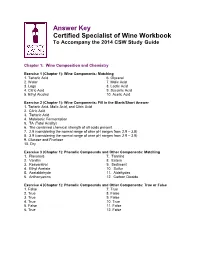

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook to Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook To Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide Chapter 1: Wine Composition and Chemistry Exercise 1 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Matching 1. Tartaric Acid 6. Glycerol 2. Water 7. Malic Acid 3. Legs 8. Lactic Acid 4. Citric Acid 9. Succinic Acid 5. Ethyl Alcohol 10. Acetic Acid Exercise 2 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Fill in the Blank/Short Answer 1. Tartaric Acid, Malic Acid, and Citric Acid 2. Citric Acid 3. Tartaric Acid 4. Malolactic Fermentation 5. TA (Total Acidity) 6. The combined chemical strength of all acids present. 7. 2.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 8. 3.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 9. Glucose and Fructose 10. Dry Exercise 3 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: Matching 1. Flavonols 7. Tannins 2. Vanillin 8. Esters 3. Resveratrol 9. Sediment 4. Ethyl Acetate 10. Sulfur 5. Acetaldehyde 11. Aldehydes 6. Anthocyanins 12. Carbon Dioxide Exercise 4 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: True or False 1. False 7. True 2. True 8. False 3. True 9. False 4. True 10. True 5. False 11. False 6. True 12. False Exercise 5: Checkpoint Quiz – Chapter 1 1. C 6. C 2. B 7. B 3. D 8. A 4. C 9. D 5. A 10. C Chapter 2: Wine Faults Exercise 1 (Chapter 2): Wine Faults: Matching 1. Bacteria 6. Bacteria 2. Yeast 7. Bacteria 3. Oxidation 8. Oxidation 4. Sulfur Compounds 9. Yeast 5. -

Marchesi Di Barolo Cellar Wine Club Notes August 2017.Pages

WINE CLUB CHRONICLE August 2017 issue no. 88 crushak.com THIS JUST IN Piemonte!!! How can we explain just how excited we are for this month’s wine club? The elusive, enigmatic wines of CELLAR WINE CLUB Piemonte are both in short supply and high demand, and you know how the economics of that usually work out… Wine: Marchesi di Barolo ‘Servaj’ Dolcetto 2015 and it’s just not everyday that an established, top-notch, Grape variety: Dolcetto Vinification: fermented and aged in stainless steel tanks total boss producer becomes available to us. Tasting notes: Can you say ch-ch-ch-ch-cherry bomb?! And then, lo and behold, an importer friend casually mentions that they might have a line on the wines of That’s we got right away on the nose of the “Servaj” Marchesi di Barolo! For context, this was one of the first Dolcetto 2015: perfectly ripe, sweetly perfumed Bing cherry spots Matt went when he biked through Piemonte. It was a fruit, tinged with almond and dried violet flowers. The no- 1982 Barolo, made by Marchesi di Barolo, that Chad oak treatment really lets the pure fruit shine, which is what Dolcetto does so well. drank when working as a busboy in the Seattle fine dining scene that turned him onto wine in the first place…oh yes. Drink: Now through 2020 We’re exultant, agog, over the moon here folks. Look Pairing: Hey, this is Italian wine after all; we had it with pizza forward to us carrying more of this producer in the future! topped with sausage and green olives, and it was a delight! Wine: Marchesi di Barolo ‘Maraia’ Barbera del Matt, Monferratto 2014 Grape variety: Barbera a.k.a. -

Vitigni) Le 5 DOCG Uno Sguardo Alle DOC L'oltrepò, Il Garda, Il Mantovano - Focus

Corso per aspiranti sommelier di II° livello Lombardia – Trentino - Emilia R. Sommelier Valerio Campigli C2 General 1 Lombardia – Trentino - Emilia R. ...Iniziamo… C2 General 2 AGENDA 1. Lombardia (Informazioni generali, vitigni) Le 5 DOCG Uno sguardo alle DOC L'Oltrepò, il Garda, il Mantovano - Focus 2. Trentino Alto Adige (Informazioni generali, vitigni) Le 8 DOC Trentodoc - Focus Vino Santo, Pinot Nero - Focus 3. Emilia Romagna (Informazioni generali, vitigni) Le 2 DOCG Uno sguardo alle DOC I Lambruschi - Focus C2 General 3 LOMBARDIA – INFORMAZIONI GENERALI Territorio pianeggiante nella parte centrale Il clima è generalmente subcontinentale, (con scarsa ventilazione nella pianura padana), diviene subalpino nella parte settentrionale. C2 General 4 LOMBARDIA – CENNI STORICI Il nome deriva da «Langbardland” la terra dei Longobardi che conquistarono l'Italia nel VI sec. La tradizione vitivinicola, pur risalendo agli Etruschi, si sviluppa nel medioevo con la diffusione dell’agricoltura monastica. Alla fine del ‘500 si inizia ad apprendere la tecnica enologica francese, inizialmente per la produzione dei chiaretti. Nel dopoguerra, le tecniche vitivinicole fanno mutare radicalmente l’ambiente e la diffusione della vite nella regione. C2 General 5 LOMBARDIA – VITICOLTURA 5 DOCG e 22 DOC. tra cui: La 1° D.O.C.G. dedicata al Metodo Classico - Franciacorta La D.O.C.G. più piccola - Moscato di Scanzo Da segnalare il Nebbiolo, che qui origina le uniche DOCG al di fuori del Piemonte. C2 General 6 LOMBARDIA – AMPELOGRAFIA Bacca Bianca Bacca Rossa Nebbiolo (Chiavennasca) Trebbiano di Lugana Moscato di Scanzo Riesling Italico Croatina Garganega Pignola Moscato Bianco Rossola Verdea Brugnola (Fortana) Groppello Lambrusco Viadanese Chardonnay Pinot Noir Cabernet Sauvignon Pinot bianco Cabernet Franc Sauvignon Blanc Merlot C2 General 7 LOMBARDIA – VITIGNI A BACCA ROSSA Chiavennasca: (Nebbiolo) ciu’ vinasca (adatto a fare vino) si trova in Valtellina dal XVI sec. -

C63 Official Journal

Official Journal C 63 of the European Union Volume 63 English edition Information and Notices 26 February 2020 Contents IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2020/C 63/01 Euro exchange rates — 25 February 2020 . 1 2020/C 63/02 Adoption of Commission Decision on the notification by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland of a modified transitional national plan referred to in Article 32 of Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on industrial emissions . 2 V Announcements PROCEDURES RELATING TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF COMPETITION POLICY European Commission 2020/C 63/03 Prior notification of a concentration (Case M.9724 — Generali/UIR/Zaragoza) Candidate case for simplified procedure (1) . 3 2020/C 63/04 Prior notification of a concentration (Case M.9547 — Johnson & Johnson/Tachosil) (1) . 5 OTHER ACTS European Commission 2020/C 63/05 Publication of an application for amendment of a specification for a name in the wine sector referred to in Article 105 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council . 6 2020/C 63/06 Publication of an application for amendment of a specification for a name in the wine sector referred to in Article 105 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council . 17 EN (1) Text with EEA relevance. Corrigenda 2020/C 63/07 Corrigendum to Call for proposals 2020 – EAC/A02/2019 – Erasmus+ Programme (OJ C 373, 5.11.2019) . 29 26.2.2020 EN Offi cial Jour nal of