An International Comparative Study of Conflict on the Waterfront

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DA 1/2015 in the Matter Between: HOSPERSA OBO TS TSHAMBI

IN THE LABOUR APPEAL COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA, DURBAN Reportable Case no: DA 1/2015 In the matter between: HOSPERSA OBO TS TSHAMBI Appellant and DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, KWAZULU –NATAL Respondent Heard: 25 February 2016 Delivered: 24 March 2016 Summary: Section 24 of the LRA provides for arbitration of disputes about the ‘interpretation or application’ of collective agreements– interpretation of – section provides for a dispute resolution device ancillary to collective bargaining, not to be used to remedy an unfair labour practice under pretext that a term of a collective agreement has been breached. The phrase ‘interpretation or application’ is not to be read disjunctively – the ‘enforcement’ of the terms of a collective agreement is a process which follows on a positive finding about ‘application’ not a facet of ‘application’. A dispute about an employer’s failure to pay an employee during period of suspension pending a disciplinary enquiry is, properly characterised, an unfair labour practice about unfair suspension as contemplated in section 186(2) (b) of the LRA. 2 An arbitrator must characterise a dispute objectively, not slavishly defer to the parties’ subjective characterisation- failure to do so is an irregularity. The determination of what constitutes a reasonable time within which to refer a dispute when no fixed period is prescribed for that category of dispute, such as a section 24 dispute, is a fact-specific enquiry having regard to the dynamics of labour relations considerations – where for example the dispute may be understood as a money claim, the prescription laws are irrelevant. Labour court reviewing and setting aside award in which arbitrator deferred to an incorrect characterisation of a dispute and ordering the matter to be heard afresh upheld and appeal against order dismissed. -

Capitalist Meltdo-Wn

"To face reality squarely; not to seek the line of least resistance; to call things by their right names; to speak t�e truth to the masses, no matter how bitter it may be; not to fear obstacles; to be true in little thi�gs as in big ones; to base one's progra.1!1 on the logic of the class struggle;. to be bold when the hour of action arrives-these are the rules of the Fourth International." 'Inequality, Unemployment & Injustice' Capitalist Meltdo-wn Global capitalism is currently in the grip of the most The bourgeois press is relentless in seizing on even the severe economic contraction since the Great Depression of smallest signs of possible "recovery" to reassure consumers the 1930s. The ultimate depth and duration of the down and investors that better days are just around thecomer. This turn remain to be seen, but there are many indicators that paternalistic" optimism" recalls similar prognosticationsfol point to a lengthy period of massive unemployment in the lowing the 1929 Wall Street crash: "Depression has reached imperialist camp and a steep fall in living standards in the or passed its bottom, [Assistant Secretary of Commerce so-called developing countries. Julius] Klein told the Detroit Board of Commerce, although 2 'we may bump along' for a while in returningto higher trade For those in the neocolonies struggling to eke out a living levels " (New Yo rk Times, 19 March 19 31).The next month, on a dollar or two a day, this crisis will literally be a matter in a major speech approved by President Herbert Hoover, of life and death. -

GLOSSARY of COLLECTIVE BARGAINING TERMS and SELECTED LABOR TOPICS

GLOSSARY of COLLECTIVE BARGAINING TERMS and SELECTED LABOR TOPICS ABEYANCE – The placement of a pending grievance (or motion) by mutual agreement of the parties, outside the specified time limits until a later date when it may be taken up and processed. ACTION - Direct action occurs when any group of union members engage in an action, such as a protest, that directly exposes a problem, or a possible solution to a contractual and/or societal issue. Union members engage in such actions to spotlight an injustice with the goal of correcting it. It further mobilizes the membership to work in concerted fashion for their own good and improvement. ACCRETION – The addition or consolidation of new employees or a new bargaining unit to or with an existing bargaining unit. ACROSS THE BOARD INCREASE - A general wage increase that covers all the members of a bargaining unit, regardless of classification, grade or step level. Such an increase may be in terms of a percentage or dollar amount. ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE – An agent of the National Labor Relations Board or the public sector commission appointed to docket, hear, settle and decide unfair labor practice cases nationwide or statewide in the public sector. They also conduct and preside over formal hearings/trials on an unfair labor practice complaint or a representation case. AFL-CIO - The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations is the national federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of fifty-six national and international unions, together representing more than 12 million active and retired workers. -

Enterprise Bargaining Agreements and the Requirement to ‘Consult’

About the Institute of Public Affairs The Institute of PuBlic Affairs is an independent, non-profit puBlic policy think tank, dedicated to preserving and strengthening the foundations of economic and political freedom. Since 1943, the IPA has been at the forefront of the political and policy debate, defining the contemporary political landscape. The IPA is funded By individual memBerships and subscriptions, as well as philanthropic and corporate donors. The IPA supports the free market of ideas, the free flow of capital, a limited and efficient government, evidence-Based puBlic policy, the rule of law, and representative democracy. Throughout human history, these ideas have proven themselves to be the most dynamic, liBerating and exciting. Our researchers apply these ideas to the puBlic policy questions which matter today. About the authors Gideon Rozner is an Adjunct Fellow at the Institute of PuBlic Affairs. He was admitted to the Supreme Court of Victoria in 2011 and spent several years practicing as a lawyer at one of Australia’s largest commercial law firms, as well as acting as general counsel to an ASX-200 company. Gideon has also worked as a policy adviser to ministers in the AbBott and TurnBull Governments. Gideon holds a Bachelor of Laws (Honours) and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of MelBourne. Aaron Lane is a Legal Fellow at the Institute of PuBlic Affairs. He specialises in employment, industrial relations, regulation and workplace law. He is a lawyer, admitted to the Supreme Court of Victoria in 2012. He has appeared before the Fair Work Commission, the Productivity Commission, and the Senate Economics Committee, among other courts and triBunals. -

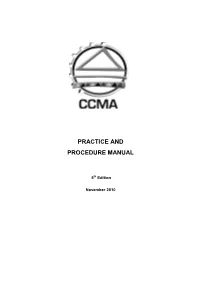

Practice and Procedure Manual

PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE MANUAL 5th Edition November 2010 101 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 101 Chapter 2 Functions, Jurisdiction and Powers Generally 201 Chapter 3 Notice and service 301 Chapter 4 Representation 401 Chapter 5 Referrals and initial administration 501 Chapter 6 Pre-conciliation 601 Chapter 7 Con-Arb 701 Chapter 8 Conciliation 801 Chapter 9 Certificates 901 Chapter 10 Settlement agreements 1001 Chapter 11 Request for arbitration, pre-arbitration procedures and subpoenas 1101 Chapter 12 Arbitrations 1201 Chapter 13 Admissibility and evaluation of evidence 1301 Chapter 14 Awards 1401 Chapter 15 Applications 1501 Chapter 16 Condonation applications 1601 Chapter 17 Rescissions and variations 1701 Chapter 18 Costs and taxation 1801 Chapter 19 Enforcement of settlement agreements and arbitration awards 1901 Chapter 20 Pre-dismissal arbitration 2001 Chapter 21 Review of arbitration awards 2101 Chapter 22 Contempt of the Commission 2201 Chapter 23 Facilitation of retrenchments in terms of section 189A of the LRA 2301 Chapter 24 Intervention in disputes in terms of section 150 of the LRA 2401 102 Chapter 25 Record of proceedings 2501 Chapter 26 Demarcations 2601 Chapter 27 Picketing 2701 Chapter 28 Diplomatic consulates and missions and international organisations 2801 Chapter 29 Index 2901 101 Chapter 1: Introduction 1.1 This manual records the practices and procedures of the CCMA. It is a work in progress and the intention is to continuously improve and update it, particularly as and when practices and procedures change. The manual is written in a question and answer format. It was not intended to cover every possible question. The questions covered are those which most commonly arise in the every day work environment. -

Download a PDF of the Issue Here

Published by the International Longshore and Warehouse Union DISPATCHER www.ilwu.org Vol 69, No 10 • NoVember 2011 THE INSIDE NEWS LETTERS TO DISPATCHER 2 Southern California ILWU members join fight to repeal Ohio anti-union bill 3 ILWU members join Occupy protests along West Coast 4 IbU workers hold the line at Georgia-Pacific 5 TRANSITIONS 8 ILWU BOOKS & VIDEO 8 Reefer madness hits west coast ports: Companies using cut-rate maintenance and repair contractors in Vietnam appear to be responsible for conditions that caused some refrigerated container units to explode, killing three dockworkers in foreign ports. ILWU members took action in October and November to protect each other – and the public – from being harmed. Historic Islais Creek Copra Crane moved landside. page 7 ILWU protects members and the public from explosive containers he ILWU is taking steps vendors in Vietnam who provided What to do with the containers? to safeguard dockworkers low-cost maintenance and servicing Many reefers were being quaran- and the public from thou- of reefers. tined at locations around the world, T but questions remained about what sands of potentially explosive What’s causing the explosions? to do with potentially at-risk con- One theory is that the fake refrig- refrigerated shipping containers tainers after they arrived on West erant may react with aluminum in that have been arriving from Coast docks. the reefer’s compressor, resulting in overseas ports. a mix that burns or explodes when “It’s impossible to know which containers might pose deadly com- Killings spark company report it comes into contact with air. -

AGREEMENT Between SHEET METAL WORKERS’ INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION LOCAL UNION No.19 CENTRAL PENNSYLVANIA AREA

AGREEMENT between SHEET METAL WORKERS’ INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION LOCAL UNION No.19 CENTRAL PENNSYLVANIA AREA 1301 South Columbus Boulevard Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19147 and ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ -EFFECTIVE - JUNE 1, 2010 through MAY 31, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUBJECT PAGE ARTICLE Apprentice & Training. 16 ……XIII Apprentice Wage Scale. 16 ……XIII, Sec 5 Asbestos . 18 ……XIV, Sec 2 Balancer’s Stamp . 2 ……II, Sec 7 Bonding . 13 ……XII, Sec 16-21 Covenant Not to Compete. 3 ……II, Sec 20 Credit Union . 4 ……III, Sec 6 Election Day . 7 ……VII, Sec 1 (b) Employer Association . 3 ……II, Sec 14 & 15 Employer Responsibilities. 1 ……II Funds. 10 ……XII Funds: Payment Rules . 11 ……XII, Sec 12 & 13 General Foreperson, Foreperson, Wages & Rules . 7 ……IX, Sec 2-5 Grievance Procedures . 20 ……XVIII Hiring Hall . 4 ……IV Holidays . 7 ……VII Hours of Work . 5 ……V H.V.A.C. Shops . 20 ……XVII, Sec 4 Job Reporting. 1 ……II, Sec 3 & 4 League for Political Education . 11 ……XII, Sec 3 Overtime . 6 ……VI Owners & Owner Members . 20 ……XVII Owner-Members Funds . 10 ……XII, Sec 2(b) Picketing . 19 ……XV Prevailing Wage Surveys . 3 ……II, Sec 17 Purchasable Items . 2 ……II, Sec 9 Reciprocal Agreements. 14 ……XII, Sec 23 Room & Board . 9 ……XI, Sec 1(c) Rules of Payment for Wages. 8 ……X Safety, Tools, & Conditions . 18 ……XIV SUB Fund. 12 ……XII, Sec 13 Scope of Work . 1 ……I Severability Clause. 22 ……XIX Shift Work . 7 ……VIII Sketcher’s Stamp. 2 ……II, Sec 6 Stewards . 20 ……XVI Sub-Contracting . 2 ……II, Sec 5 & 8 Successor Clause. 4 ……II, Sec 21 Term of Agreement. -

Wages and Work Practices in Union and Open Shop

WAGES AND WORK PRACTICES IN UNION AND OPEN SHOP CONSTRUCTION by Clinton Currier Bourdon Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on December 15, 1982 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctorate in Philosophy This is the most complete text of the thesis available. The following page(s) were not included in the copy of the thesis deposited in the Institute Archives by the author: (title page) MASSACHUStTS NSTTUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 0cT 208 6 4~A~8 Abstract WAGES AND WORK PRACTICES IN UNION AND OPEN SHOP CONSTRUCTION by Clinton Currier Bourdon Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on December 15, 1982 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctorate in Philosophy ABSTRACT Craft unions in the construction industry have long enjoyed relatively high hourly wages and benefits and have played major roles in the training, hiring, and assignment of construction labor. But in the 1970s they became increasingly threatened by the widespread growth of nonunion construction firms and labor. This spread of nonunion firms in the industry permits a detailed comparison of compensation and work practices in the union and open shop sectors of construction. This comparison allows a unique analysis of the union impact on both compen- sation and construction labor market institutions. A single-equation econometric estimation of the union/nonunion wage differential in construction using a micro-data base on workers' wages, characteristics, and union status provided evidence of a union wage differential in construction exceeding fifty percent. But further analysis showed that this estimate may be biased upward by the heter- eogenity of skills and occupations in construction as well as by the positive correlation of wages and union status. -

The Commercial Temp Agency, the Union Hiring Hall, and the Contingent Workforce: Toward a Legal Reclassification of For-Profit Labor Market Intermediaries

Upjohn Institute Press The Commercial Temp Agency, the Union Hiring Hall, and the Contingent Workforce: Toward a Legal Reclassification of For-Profit Labor Market Intermediaries Harris Freeman University of Massachusetts Amherst George Gonos State University of New York - Potsdam Chapter 13 (pp. 275-304) in: Justice on the Job: Perspectives on the Erosion of Collective Bargaining in the United States Richard N. Block, Sheldon Friedman, Michelle Kaminski, Andy Levin, eds. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2006 DOI: 10.17848/9781429454827.ch13 Copyright ©2006. W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. All rights reserved. 13 The Commercial Temp Agency, the Union Hiring Hall, and the Contingent Workforce Toward a Legal Reclassification of For-Profit Labor Market Intermediaries Harris Freeman Western New England College School of Law and Labor Relations and Research Center, University of Massachusetts, Amherst George Gonos State University of New York at Potsdam An integral feature of today’s volatile labor markets is the perva- sive use of temporary help and staffing firms to respond to the cycli- cal economy’s fluctuating labor needs. Modern workplace law has not kept pace with this development. Federal labor law was enacted and developed during the middle decades of the twentieth century to gov- ern stable, long-term employment relationships, not the vicissitudes of the now-ubiquitous temporary work relationship. The Labor Manage- ment Relations Act (LMRA) does not address temporary work in the statutory text, -

Teamster Stewards Make a Difference a Comprehensive Guide for Today’S Teamster Steward

Teamster Stewards Make a Difference A comprehensive guide for today’s Teamster Steward An Important Message for Teamster Stewards Dear Teamster Steward: Thank you for serving as a Union leader at your worksite. To your co- workers who look to you for guidance, support and strength, you ARE the Union in action. What you say counts. How well you listen counts. How well you respond to your members’ questions and concerns counts. You are the leader they look to for everyday assistance and results. Being a leader is no small task. To help you sharpen your skills and prepare for the tough challenges ahead, we have created this guide especially for you. We encourage you to read the information and learn what’s expected of you as a union steward. You can make a difference to the 1.4 million men and women who comprise the Teamsters Union. Thank you for undertaking what we believe is one of the most important jobs in our union, that of union steward. Your hard work and dedication will make a big difference as we face the tough challenges ahead. Fraternally yours, James P. Hoffa Ken Hall General President General Secretary-Treasurer Teamster Stewards Make a Difference Table of Contents Chapter 1 Why Stewards? 1 Chapter 2 Getting Started 7 Chapter 3 Getting Involved, Staying Involved 13 Chapter 4 All About Grievances 19 Chapter 5 The Formal Grievance Procedure 31 Chapter 6 Know Your Rights 41 Chapter 7 Stewards As Organizers 59 Chapter 8 Appendix 67 Why Stewards? Why Stewards? “Teamster Stewards as Leaders in the Workplace” Introduction task. -

Industrial Relations Act 2016

Queensland Industrial Relations Act 2016 Current as at 31 August 2017 Queensland Industrial Relations Act 2016 Contents Page Chapter 1 Preliminary Part 1 Introduction 1 Short title . 47 2 Commencement . 47 3 Main purpose of Act . 47 4 How main purpose is primarily achieved . 48 5 Act binds all persons . 50 Part 2 Interpretation 6 Definitions . 50 7 Who is an employer . 50 8 Who is an employee . 51 9 What is an industrial matter . 51 Part 3 General overview of scope of Act 10 Purpose of part . 52 11 Definition for part . 52 12 Who this Act applies to generally . 52 13 Who this Act applies to—particular provisions . 54 Chapter 2 Modern employment conditions Part 1 Preliminary 14 Definitions for chapter . 54 15 Meaning of long term casual employee . 55 Part 2 Interaction of elements of industrial relations system 16 What part is about . 55 17 Relationship between Queensland Employment Standards and other laws . 56 18 Relationship between Queensland Employment Standards and industrial instruments . 56 Industrial Relations Act 2016 Contents 19 Relationship of modern award with certified agreement . 56 20 Relationship of modern award with contract of service . 57 Part 3 Queensland Employment Standards Division 1 Preliminary 21 Meaning of Queensland Employment Standards . 57 Division 2 Minimum wage 22 Entitlement to minimum wage . 58 Division 3 Maximum weekly hours 23 Maximum weekly hours . 58 24 Applicable industrial instruments may provide for averaging of hours of work . 59 25 Averaging of hours of work for employees not covered by applicable industrial instruments . 60 26 Deciding whether additional hours are reasonable . -

Final Thesis 2014

TEMPORARY AGENCY WORKERS IN THE FRENCH CAR INDUSTRY: WORKING UNDER A NEW VARIANT OF ‘DESPOTISM’ IN THE LABOUR PROCESS Christina Purcell A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Business Department of Management Manchester Metropolitan University April 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .........................................................................................................4 DECLARATION ..........................................................................................................................5 ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................6 ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................................................................7 LISTE OF TABLES .....................................................................................................................8 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................9 Neo-liberalisation, labour market flexibility and the growth of agency work in Europe ..........14 The growth of temporary agency work in car manufacturing ...................................................15 Temporary agency work and labour process analysis ................................................................17 Thesis aims ................................................................................................................................19