Author Report No Available From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hybrid Winds

Hybrid Winds Linsey Pollak When I was about fifteen I had a dream that featured a wind instrument lives on the Sunshine Coast in whose sound I remembered clearly on Queensland and is a renowned waking. It reminded me of a somewhat community music facilitator, mellow crumhorn (Renaissance wind- composer and musical director who capped double reed pipe) or a sort of has built instruments for over 20 high-pitched baritone sax. That sound Figure 1: Gaidanet. years, specialising in aerophones eludes me now, for I have always been chasing that elusive, dreamt, wind- a semitone when it is opened. In fact it from Eastern Europe. He has a instrument sound. only works for the top half of the octave reputation for making and playing I started my instrument making in Macedonian gaidas, but for the full instruments made from rubber journey 25 years ago making bamboo range in Bulgarian gaidas which have a gloves, carrots, watering cans, flutes. That quickly led to a longer stint more conical bore. This enables a unique chairs, brooms, bins and other found of making wooden renaissance flutes, style of playing and ornamentation. objects. His ongoing obsession and an interest in other Renaissance and What I wanted to do was to have combines much of this: making medieval winds. But the real love affair access to the gaida style of playing and ornamentation while playing a lip-blown music more accessible to began 20 years ago with the Macedonian instrument like a clarinet. I experimented communities through instrument gaida (bagpipes), and so I travelled to Macedonia for eight months over three first with a clarinet mouthpiece and a building and playing workshops. -

The Genesis Discography

TTHHEE GGEENNEESSIISS DDIISSCCOOGGRRAAPPHHYY “The scattered pages of a book by the sea…” 1967-1996 Page 2 The Genesis Discography The Genesis Discography January 1998 Edition Copyright © 1998 Scott McMahan, All Rights Reserved The Genesis Discography Page 3 THE EXODUS ENDS “And then there was the time she sang her song, and nobody cried for more…” “I think that in the end, if all else is conqured, Bombadil will fall, Last as he was First, and then Night will come.” … from the Council of Elrond, in Lord of the Rings Indeed, since its beginning in 1993, The Genesis Discography has been a fixture on the Internet much like Tom Bombadil was in Middle Earth. It has endured in the face of the changing times, without itself changing much, isolated off in its own world. Glorfindel had the opinion that Bombadil would be the last to fall, after all else was lost, last as he was first. In Tolkien’s story, that opinion was never tested. Good triumphed over evil, and everyone lived happily ever after. Not true on the Internet. Since 1993, the forces of evil have created a desolation and oppression that Sauron even with the help of his ruling ring could not imagine perpetrating. From the days of the Internet as an academic research network until today’s Internet I have witnessed ruination unbelieveable. The decay, corruption, and runiation of the Internet boggles my mind. Like Tom Bombadil in his carefully demarcated borders, The Genesis Discography has been an island in the storm, surrounded on all sides but never giving in. -

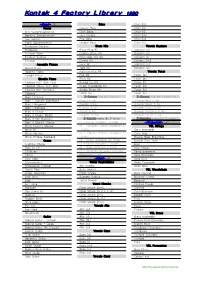

Kontak 4 Factory Library.Hwp

KontakKontak 44 FactoryFactory LibraryLibrary 12801280 -Band- 76 Bass Choir [a] Horns Classic Bass Choir [e] Alto Saxophone(mono) Funk Bass Choir [i] Baritone Saxophone(m) Jazz Upright Choir [m] Sax Section Pop Bass Choir [o] Tenor Saxophone(m) Upright Bass Choir [u] Trombone Section Drum Kits Vowels Soprano Trombone Bling Bling Kit Soprano [a] Trumpet Mute Central Stage Kit Soprano [e] Trumpet Section Chocolate City Kit Soprano [i] Trumpet Crystal Kit Soprano [m] Acoustic Pianos Funk Kit Soprano [o] Grand Piano Jazz Kit Soprano [u] Ragtime Piano Platinum Plus Kit Vowels Tenor Upright Piano Pop Kit Tenor [a] Electric Piano Rock Kit Tenor [e] Clavinet Auto Wah Lead Rolling Ice Kit Tenor [i] Clavinet Stereo Auto Wah Street Knowledge Kit Tenor [m] Clavinet Wah Overdrive Studio Break Kit Tenor [o] Clavinet Urban Kit Tenor [u] Mark I Classic Z-Groups nkg file 5 folder Z-Groups nkg file 5 folder 30 Mark I Crunchy Expressive (Bass) 4 file (Vowels Alto) 6 file Mark I Ringmod (Guitar) 5 file (Vowels Bass) 6 file Mark I Suitcase (Horns) 9 file (Vowels Choir) 6 file Mark II Classic (Keys) 6 file (Vowels Soprano) 6 file Mark II Phaser Ballad (Organ) 19 file (Vowels Tenor) 6 file Mark II Soft Random Z-Sample wma file 8 folder Z-Samples wma file 17 folder Mark II Sparkly Chorus (1 - Horns Samples) 8 folder -Orchestral- 561 Wurly Crunchy Mellow (2 - Acoustic Pianos Samples) 2 VSL Strings Wurly EP folder Cello Ensemble Wurly Speaker (3 - Electric Pianos Samples) 4 Cello Solo Wurly Vintage Slapback folder Double Bass Ensemble Organ (4 - Organ Samples) -

Makams – Rhythmic Cycles and Usûls

https://doi.org/10.5771/9783956506734, am 26.09.2021, 20:13:18 Open Access - http://www.nomos-elibrary.de/agb https://doi.org/10.5771/9783956506734, am 26.09.2021, 20:13:18 Open Access - http://www.nomos-elibrary.de/agb Post-Byzantine Music Manuscripts as a Source for Oriental Secular Music (15th to Early 19th Century) © 2016 Orient-Institut Istanbul https://doi.org/10.5771/9783956506734, am 26.09.2021, 20:13:18 Open Access - http://www.nomos-elibrary.de/agb ISTANBULER TEXTE UND STUDIEN HERAUSGEGEBEN VOM ORIENT-INSTITUT ISTANBUL BAND 28 © 2016 Orient-Institut Istanbul https://doi.org/10.5771/9783956506734, am 26.09.2021, 20:13:18 Open Access - http://www.nomos-elibrary.de/agb Post-Byzantine Music Manuscripts as a Source for Oriental Secular Music (15th to Early 19th Century) by Kyriakos Kalaitzidis Translation: Kiriaki Koubaroulis and Dimitri Koubaroulis WÜRZBURG 2016 ERGON VERLAG WÜRZBURG IN KOMMISSION © 2016 Orient-Institut Istanbul https://doi.org/10.5771/9783956506734, am 26.09.2021, 20:13:18 Open Access - http://www.nomos-elibrary.de/agb Umschlaggestaltung: Taline Yozgatian Umschlagabbildung: Gritsanis 8, 323 (17th c.): “From here start some songs and murabba’s” Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. ISBN 978-3-95650-200-2 ISSN 1863-9461 © 2016 Orient-Institut Istanbul (Max Weber Stiftung) Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. -

The Shakuhachi and the Ney: a Comparison of Two Flutes from the Far Reaches of Asia

1 The Shakuhachi and the Ney: A Comparison of Two Flutes from the Far Reaches of Asia Daniel B. RIBBLE English Abstract. This paper compares and contrasts two bamboo flutes found at the opposite ends of the continent of Asia. There are a number of similarities between the ney, or West Asian reed flute and the shakuhachi or Japanese bamboo flute, and certain parallels in their historical development. even though the two flutes originated in completely different socio-cultural contexts. One flute developed at the edge of West Asia, and can be traced back to an origin in ancient Egypt, and the other arrived in Japan from China in the 8 th century and subsequently underwent various changes over the next millenium. Despite the differences in the flutes today, there may be some common origin for both flutes centuries ago. Two reed·less woodwinds Both flutes are vertical, endblown instruments. The nay, also spelled ney, as it is referred to in Turkey or Iran, and as the nai in Arab lands, is a rim blown flute of Turkey, Iran, the Arab countries, and Central Asia, which has a bevelled edge made sharp on the inside, while the shakuhachi is an endblown flute of Japan which has a blowing edge which is cut at a downward angle towards the outside from the inner rim of the flute. Both flutes are reed less woodwinds or air reed flutes. The shakuhachi has a blowing edge which is usually fitted with a protective sliver of water buffalo horn or ivory, a development begun in the 17 th century. -

Joël Bons E C | P Music1 Air#3In C Contextair#4 Air#0 Air#1 Air#2 Joël Bons

Joël Bons E C | P Music1 air#3in C contextair#4 air#0 air#1 air#2 Joël Bons Invitation / 3 The international music world is increasingly shaped by music from diverse cultures. However, almost no structural research has been performed into the impact this has, or might have in the future, on musicians in training. air#3 That the distinction between composition and performance differs according to culture is also an area of interest. The Amsterdam Conservatory has invited Joël Bons to investi- gate the opportunities arising from the combination of differ- ent music cultures, for both composition and performance prac- tice. Particular attention will be given to bringing these two practices closer to one another. Where possible he will, in response to his findings, advise the Board on the selection of guest tutors and other teaching air#4 staff, the development and reform of the curriculum, and the programming of the Composition Department. In addition, the Amsterdam Conservatory has asked Joël Bons to investigate the feasibility of a Centre of Excellence at the Conservatory devoted to various aspects of non-Western music, namely knowledge, research, composition and performance. air#0 air#1 From the letter of appointment air#2 Joël Bons Joël Bons studied guitar and composition at the Sweelinck Conservatory in 4 5 Amsterdam. After completion of his composition studies, he attended summer Winds courses by Franco Donatoni in Siena and the Darmstädter Ferienkurse für Neue Musik. In 1982 he resumed his composition studies, with Brian Ferneyhough in Freiburg. and Strings At the beginning of the 1980s, Joël Bons co-founded the Nieuw Ensemble, a leading 3 international ensemble for contemporary music that is pioneering in its programming (02–2005) / and innovative in its repertoire. -

Conference Schedule with Abstracts, Program Notes, Bios and Emails

2009 CMS South Central Regional Conference University of Oklahoma School of Music Hosts: Dr. Paula Conlon and Dr. Marvin Lamb Conference Schedule with Abstracts, Program Notes, Bios and Emails 1 2009 CMS South Central Chapter Conference Table of Contents Schedule ……………………………………………………...……………………. 3 Abstracts …………………………………………………………………………… 13 Program Notes ……………………………………………………………………... 30 Bios ………………………………………………………………………………… 39 Email List ………………………………………………………………………….. 58 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Conference co-chairs Paula Conlon and Marvin Lamb would like to thank the Executive and Regional offices of The College of Music Society and the University of Oklahoma School of Music for co-sponsoring this conference, and thank CMS South Central Chapter President Nico Schüler, CMS South Central Chapter Officers, Assistant Coordinator Christina Giacona, Erin Fehr, Russell Pettitt, John Ernst and Patrick Conlon for their help in organizing, making up the program and helping out at the conference. 2 2009 CMS South Central Regional Conference Schedule NOTE: All events in Catlett Music Center (CMC), 500 W. Boyd Conference Registration: March 13-14, 7:30am – 8:00pm, Gothic Hall [Foyer of Catlett] March 15, 7:30am – 1:00pm, Gothic Hall The Listening & Reading Room: March 13-14, 8:00am – 8:00pm, CMC 139 [Below organ] Friday, March 13, 2009 8:00 AM – 9:00 AM Paper Session I, CMC 242 Chair: Dorothea Gail, University of Oklahoma “Beyond ‘Failed’ Forms: Defining Normative Procedures in Shostakovich’s Use of Sonata Form” Sarah Reichardt, University of Oklahoma “Voice -

THE MAKING of the TURKISH NEY Alan Whenham-Prosser

ICONEA 2012-2015, XX-XX the Mathnavi. Should we compare the scope of the modern flute with the Ney we would find 14 scales on the modern type with more than 200 on the Ney. The modern flute has a span of twelve notes in the octave while the Ney has at least 34. In melodic terms this shows that the Ney responded to a THE MAKING OF THE micro-tonal system which should not be considered as primitive or less sophisticated, but rather, that TURKISH NEY we should consider that early Ney music was very developed and used a complex melodic system, a fact which might be difficult to understand in Alan Whenham-Prosser terms of modern Western music theory. Introduction The Ney is an ancient flute made from a length of bamboo reed. A man playing the Ney is represented in a tomb painting from the Egyptian fifth Dynasty, dating from over 2,000 years B.C. Figure 2. (Fig. 1). We can also clearly see nine sections of Sourcing the reeds and making the Ney the reed, a detail of importance in the facture of The reeds from which the Ney is made is the the Ney. Arundo Donax variety. It is the same material which is used for clarinets, oboes and saxophones reeds. It is a member of the grass family. This type of reed was originally growing in the Mediterranean perifery. Therefore Ancient Egyptians, Babylonians and cultures in the Near and Middle East would have had abundance of them for their flutes. In modern times the rhizomes have been exported to round the world and reeds grown from them are now used for fence making, basket weaving, ethanol bio-fuel production, paper making and other purposes. -

2002 Smithsonian Folklife Festival

Smithsonian Folklife Festival records: 2002 Smithsonian Folklife Festival CFCH Staff 2017 Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 600 Maryland Ave SW Washington, D.C. [email protected] https://www.folklife.si.edu/archive/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical note.................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents note................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 2 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Program Books, Festival Publications, and Ephemera, 2002................... 6 Series 2: The Silk Road: Connecting Cultures, Creating Trust................................ 7 Smithsonian Folklife Festival records: 2002 Smithsonian -

1 Turkish Classical Clarinet Repertoire

Turkish Classical Clarinet Repertoire: Performance, Accessibility, and Integration into the Canon, with a Performance Guide to Works by Edward J. Hines and Ahmet Adnan Saygun D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sarah Elizabeth Korneisel Jaegers Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. David Clampitt Professor Katherine Borst Jones Dr. Russel C. Mikkelson 1 Copyrighted by Sarah Elizabeth Korneisel Jaegers 2019 2 Abstract While American and western European works make up the majority of the classical clarinet repertoire known and studied in the West, works of Turkish origin are the focus of this document. Though over 100 pieces of Turkish classical clarinet repertoire exist, they are widely unknown to Western musicians, uncatalogued, and seldom performed. Consequently, although the clarinet is a staple of Turkish music and is extremely popular in the country’s folk tradition, classical clarinet music by Turkish composers remains difficult for Western musicians to find and acquire. The history of Anatolia as a cultural melting pot resulted in diverse and unique classical and folk musical traditions, both based on the makam modal system. Unlike the Western tradition, which developed twelve-tone equal temperament, the octave in the Turkish modal system comprises twenty-four unequally-spaced tones. The clarinet was introduced to Turkey by Giuseppe Donizetti (1788–1856), who traveled to Turkey at the behest of the sultanate to found European-style bands. Particularly appreciated was the clarinette d’amour, pitched in G. -

THE IDEALIZED WORLD of MALORY's "MORTE DARTHUR": a Study of the Elements of Myth, Allegory, and Symbolism in the Secul

THE IDEALIZED WORLD OF MALORY'S "MORTE DARTHUR": A Study of the Elements of Myth, Allegory, and Symbolism in the Secular and Religious Milieux of Arthurian Romance by MURIEL A. I. WHITAKER A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1970 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree tha permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Date 7 T ABSTRACT Towards the end of the Middle Ages, Sir Thomas Malory synthesized the diverse elements of British chronicle history, Celtic myth, French courtoisie, and Catholic theology which over a period of six hundred years or more had gathered about the legendary figure of King Arthur. Furthermore, Malory presented in definitive form the kind of idealized milieu that later writers in English came to regard as romantic. Malory's Morte Darthur presents dramatically the activities of a mythic aristocratic society living in a golden age. It preserves the "history" of a British king who defeats the Emperor of Rome and establishes an empire stretching from Ireland and Scandinavia to the Eastern Mediterranean. -

Effective Learning and Teaching Strategies for Ney Classes for the 9St and 10Nd Grades of Fine Arts High Schools

RAST MÜZİKOLOJİ DERGİSİ Uluslararası Müzikoloji Dergisi www.rastmd.com Doi:10.12975/rastmd.2016.04.02.00074 EFFECTIVE LEARNING AND TEACHING STRATEGIES FOR NEY CLASSES FOR THE 9ST AND 10ND GRADES OF FINE ARTS HIGH SCHOOLS Erhan Özden* ABSTRACT This study has been prepared in accordance with the general objectives and basic principles of Turkish national education as stated in the National Education Act no. 1739.1 This curriculum aims at educating students to comprehend the place of the Ney as a musical instrument in Turkish music culture, to acquire the skills necessary to produce sounds accurately and in harmony with other instruments, to extend their instrumental and vocal repertoire, and to develop a sense of responsibility in both individual and group performances. Keywords: the Ney -Reed Flute-, Education, Program, Unit, Curriculum GÜZEL SANATLAR LİSELERİNİN 9. ve 10. SINIFLARINA YÖNELİK NEY ÖĞRETİMİNDE ETKİLİ ÖĞRENME VE ÖĞRETME YÖNTEMLERİ ÖZET Bu çalışma 1739 sayılı Milli Eğitim Temel Kanunu’nun 2. maddesinde ifade edilen Türk Milli Eğitiminin genel amaçları ile Türk Milli Eğitimin Temel İlkeleri esas alınarak hazırlanmıştır. Bu program ile öğrencilerin; Türk musikisinin en temel çalgılarından biri olan ney sazının Türk müzik kültüründeki yerini anlamaları, Neyden doğru ses çıkartarak diğer sazlarla yakalanması gereken ahenk birliğini kazanmaları, Saz repertuvarının yanı sıra sözlü repertuvara yönelik eser dağarcığı oluşturmaları ve gerek bireysel gerekse grup çalışmalarında sorumluluk duygusunu kazanmaları amaçlanmaktadır. ANAHTAR KELİMELER: Ney, Eğitim, Program, Ünite, Müfredat INTROCUTION Highly popular in several music traditions, the Ney is an end-blown woodwind instrument which has a very special place especially in classical Turkish music with its special * Assoc.