Vexillology of the Anglo-Boer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Past Veterinarians in South Africa

PAST VETERINARIANS IN SOUTH AFRICA VOLUME 2 M – Z P J POSTHUMUS BVSc M.B.E. 10th EDITION 123 MAAG, ALFONS (2/7/1866 - 26/1/1933) 7 Born Edinburgh, Germany on 2/7/1886 he graduated f ~~~ the f university in Stuttgart in 1908. In 1914 he came to South, Africa as a Government veterinary Officer under the German Government, but was dismissed from his post when the country was captured by the South African Forces in 1915. From 1915 to 1919 he was ~unemployed as a veterinarian, but greatly assisted with the flu epidemic. For his work in this epidemic he was awarded the Red Cross Medal . In 1922 he, Schmid and Sigwart were appointed by the South West Africa administration and it is interesting to note that these three veterinarians were the only former German officials to be so re-employed. After his appointment he was stationed at Gobabis until his health failed. He died from cancer in his home town in Germany on 26/1/1933. MACDONALD, RODERICK (26/12/1874 - Born in Scotland on 26/12/1874 he qualified as a veterinarian at the university of Ontario Vet. College, Canada in 1891. In 1900 he came to South Africa as a Civil Veterinarian attached to the Army veterinary Department to take part in the Boer War. After the war he joined the volunteer corps i n 1903 and after serving as a trooper in its ranks was promoted to Vety Lieutenant on 15/11/1907 and transferred to the East Rand Mounted Rifles (left wing of the Imperial Light Horse). -

Boer War Association Queensland

Boer War Association Queensland Queensland Patron: Major General Professor John Pearn, AO RFD (Retd) Monumentally Speaking - Queensland Edition Committee Newsletter - Volume 12, No. 1 - March 2019 As part of the service, Corinda State High School student, Queensland Chairman’s Report Isabel Dow, was presented with the Onverwacht Essay Medal- lion, by MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD. The Welcome to our first Queensland Newsletter of 2019, and the messages between Ermelo High School (Hoërskool Ermelo an fifth of the current committee. Afrikaans Medium School), South Africa and Corinda State High School, were read by Sophie Verprek from Corinda State Although a little late, the com- High School. mittee extend their „Compli- ments of the Season‟ to all. MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD, together with Pierre The committee also welcomes van Blommestein (Secretary of BWAQ), laid BWAQ wreaths. all new members and a hearty Mrs Laurie Forsyth, BWAQ‟s first „Honorary Life Member‟, was „thank you‟ to all members who honoured as the first to lay a wreath assisted by LTCOL Miles have stuck by us; your loyalty Farmer OAM (Retd). Patron: MAJGEN John Pearn AO RFD (Retd) is most appreciated. It is this Secretary: Pierre van Blommestein Chairman: Gordon Bold. Last year, 2018, the Sherwood/Indooroopilly RSL Sub-Branch membership that enables „Boer decided it would be beneficial for all concerned for the Com- War Association Queensland‟ (BWAQ) to continue with its memoration Service for the Battle of Onverwacht Hills to be objectives. relocated from its traditional location in St Matthews Cemetery BWAQ are dedicated to evolve from the building of the mem- Sherwood, to the „Croll Memorial Precinct‟, located at 2 Clew- orial, to an association committed to maintaining the memory ley Street, Corinda; adjacent to the Sherwood/Indooroopilly and history of the Boer War; focus being descendants and RSL Sub-Branch. -

Wooltru Healthcare Fund Optical Network List Gauteng

WOOLTRU HEALTHCARE FUND OPTICAL NETWORK LIST GAUTENG PRACTICE TELEPHONE AREA PRACTICE NAME PHYSICAL ADDRESS CITY OR TOWN NUMBER NUMBER ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE ACTONVILLE 084 6729235 AKASIA 7033583 MAKGOTLOE SHOP C4 ROSSLYN PLAZA, DE WAAL STREET, ROSSLYN AKASIA 012 5413228 AKASIA 7025653 MNISI SHOP 5, ROSSLYN WEG, ROSSLYN AKASIA 012 5410424 AKASIA 668796 MALOPE SHOP 30B STATION SQUARE, WINTERNEST PHARMACY DAAN DE WET, CLARINA AKASIA 012 7722730 AKASIA 478490 BODENSTEIN SHOP 4 NORTHDALE SHOPPING, CENTRE GRAFENHIEM STREET, NINAPARK AKASIA 012 5421606 AKASIA 456144 BODENSTEIN SHOP 4 NORTHDALE SHOPPING, CENTRE GRAFENHIEM STREET, NINAPARK AKASIA 012 5421606 AKASIA 320234 VON ABO & LABUSCHAGNE SHOP 10 KARENPARK CROSSING, CNR HEINRICH & MADELIEF AVENUE, KARENPARK AKASIA 012 5492305 AKASIA 225096 BALOYI P O J - MABOPANE SHOP 13 NINA SQUARE, GRAFENHEIM STREET, NINAPARK AKASIA 087 8082779 ALBERTON 7031777 GLUCKMAN SHOP 31 NEWMARKET MALL CNR, SWARTKOPPIES & HEIDELBERG ROAD, ALBERTON ALBERTON 011 9072102 ALBERTON 7023995 LYDIA PIETERSE OPTOMETRIST 228 2ND AVENUE, VERWOERDPARK ALBERTON 011 9026687 ALBERTON 7024800 JUDELSON ALBERTON MALL, 23 VOORTREKKER ROAD, ALBERTON ALBERTON 011 9078780 ALBERTON 7017936 ROOS 2 DANIE THERON STREET, ALBERANTE ALBERTON 011 8690056 ALBERTON 7019297 VERSTER $ VOSTER OPTOM INC SHOP 5A JACQUELINE MALL, 1 VENTER STREET, RANDHART ALBERTON 011 8646832 ALBERTON 7012195 VARTY 61 CLINTON ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 011 9079019 ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN 26 VOORTREKKER STREET ALBERTON 011 9078745 -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

The Role and Application of the Union Defence Force in the Suppression of Internal Unrest, 1912 - 1945

THE ROLE AND APPLICATION OF THE UNION DEFENCE FORCE IN THE SUPPRESSION OF INTERNAL UNREST, 1912 - 1945 Andries Marius Fokkens Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Military Science (Military History) at the Military Academy, Saldanha, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Lieutenant Colonel (Prof.) G.E. Visser Co-supervisor: Dr. W.P. Visser Date of Submission: September 2006 ii Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously submitted it, in its entirety or in part, to any university for a degree. Signature:…………………….. Date:………………………….. iii ABSTRACT The use of military force to suppress internal unrest has been an integral part of South African history. The European colonisation of South Africa from 1652 was facilitated by the use of force. Boer commandos and British military regiments and volunteer units enforced the peace in outlying areas and fought against the indigenous population as did other colonial powers such as France in North Africa and Germany in German South West Africa, to name but a few. The period 1912 to 1945 is no exception, but with the difference that military force was used to suppress uprisings of white citizens as well. White industrial workers experienced this military suppression in 1907, 1913, 1914 and 1922 when they went on strike. Job insecurity and wages were the main causes of the strikes and militant actions from the strikers forced the government to use military force when the police failed to maintain law and order. -

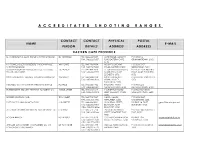

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Hoofstuk 10 Ondersteuning Van Militere

HOOFSTUK 10 ONDERSTEUNING VAN MILITERE AKTIWITEITE DEUR DIE VAALDRIEHOEKSE GEMEENSKAP 10.1 INLEIDING Reeds in die Tweede Wereldoorlog was daar pogings in die Vaaldriehoek om die oorlog te ondersteun.1 Net so is in die era 1974-1994 verskillende pogings deur die gemeenskap van die Vaaldriehoek geloods om die verdedigingspoging van voorgenoemde tydperk te ondersteun. As gevolg van diensplig en grensdiens sedert die sewentige~are, is die gemeenskap toenemend by militere aktiwiteite betrek.2 Veral vroue-organisasies het die verdedigingspoging aktief ondersteun.3 Die bree blanke gemeenskap het geldelik bygedra omdat hulle seuns by die weermag of polisie betrokke was. Daar was pogings om teruggekeerde dienspligtiges weer in die samelewing te laat inskakel. lnsamelingsprojekte is vir die grenssoldate aangepak, vervoerreelings vir dienspligtiges getref en die bonusobligasieveldtog is ook ondersteun. Werkgewers het soldate met salarisse tegemoet gekom. Die weermag het aan die ander kant op verskillende wyses bygedra om die gemeenskap te ondersteun. 1 Vgl. Vaal Teknorama (VTR), Houer stadsraaddokumente, Leer Warfund drives, Brief van die organiseerder van Military Cavalcade: Woman's Section Liberty Cavalcade aan burgemeester van Vereeniging, 02.01.1942. 2 J. Cock, Manpower and militarisation; woman in the SADF in J. Cock & L. Nathan (eds.)., War and society: The m~itarisation of South African politics (Johannesburg, David Phillip, 1989), p. 52; E. Fourie, "Ek praatmy hart uit", Paratus, 29(4), Aparil1978, p. 10. 3 J. Cock, Manpower and militarisation; -

The Psychological Impact of Guerrilla Warfare on the Boer Forces During the Anglo-Boer War

University of Pretoria etd - McLeod AJ (2004) THE PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACT OF GUERRILLA WARFARE ON THE BOER FORCES DURING THE ANGLO-BOER WAR by ANDREW JOHN MCLEOD Submitted as partial requirement for the degree DOCTOR PHILOSOPHIAE (HISTORY) in the Faculty of Human Sciences University of Pretoria Pretoria 2004 Supervisor : Prof. F. Pretorius Co-supervisor : Prof. J.B. Schoeman University of Pretoria etd - McLeod AJ (2004) Abstract of: “The psychological impact of guerrilla warfare on the Boer forces during the Anglo- Boer War” The thesis is based on a multi disciplinary study involving both particulars regarding military history and certain psychological theories. In order to be able to discuss the psychological experiences of Boers during the guerrilla phase of the Anglo-Boer War, the first chapters of the thesis strive to provide the required background. Firstly an overview of the initial conventional phase of the war is furnished, followed by a discussion of certain psychological issues relevant to stress and methods of coping with stress. Subsequently, guerrilla warfare as a global concern is examined. A number of important events during the transitional stage, in other words, the period between conventional warfare and total guerrilla warfare, are considered followed by the regional details concerning the Boers’ plans for guerrilla warfare. These details include the ecological features, the socio-economic issues of that time and military information about the regions illustrating the dissimilarity and variety involved. In the chapters that follow the focus is concentrated on the psychological impact of the guerrilla war on the Boers. The wide range of stressors (factors inducing stress) are arranged according to certain topics: stress caused by military situations; stress caused by the loss of infrastructure in the republics; stress caused by environmental factors; stress arising from daily hardships; stress caused by anguish and finally stressors prompted by an individuals disposition. -

National Liquor Authority Register

National Liquor Register Q1 2021 2022 Registration/Refer Registered Person Trading Name Activities Registered Person's Principal Place Of Business Province Date of Registration Transfer & (or) Date of ence Number Permitted Relocations or Cancellation alterations Ref 10 Aphamo (PTY) LTD Aphamo liquor distributor D 00 Mabopane X ,Pretoria GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 12 Michael Material Mabasa Material Investments [Pty] Limited D 729 Matumi Street, Montana Tuine Ext 9, Gauteng GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 14 Megaphase Trading 256 Megaphase Trading 256 D Erf 142 Parkmore, Johannesburg, GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 22 Emosoul (Pty) Ltd Emosoul D Erf 842, 845 Johnnic Boulevard, Halfway House GP 2016-10-07 N/A N/A Ref 24 Fanas Group Msavu Liquor Distribution D 12, Mthuli, Mthuli, Durban KZN 2018-03-01 N/A 2020-10-04 Ref 29 Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd D Erf 19, Vintonia, Nelspruit MP 2017-01-23 N/A N/A Ref 33 Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd D 117 Foresthill, Burgersfort LMP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 34 Media Active cc Media Active cc D Erf 422, 195 Flamming Rock, Northriding GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 52 Ocean Traders International Africa Ocean Traders D Erf 3, 10608, Durban KZN 2016-10-28 N/A N/A Ref 69 Patrick Tshabalala D Bos Joint (PTY) LTD D Erf 7909, 10 Comorant Road, Ivory Park GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 75 Thela Management PTY LTD Thela Management PTY LTD D 538, Glen Austin, Midrand, Johannesburg GP 2016-04-06 N/A 2020-09-04 Ref 78 Kp2m Enterprise (Pty) Ltd Kp2m Enterprise D Erf 3, Cordell -

The London Gazette.>

27459. 4833 The London Gazette.> $u6ltsj)el> bg 9utl)ontg. TUESDAY, JULY 29, 1902* By the KING. By the KING. A PROCLAMATION For appointing a Day for the Celebration of the A PROCLAMATION Solemnity of the Coronation of Their Majesties.AngloBoerWar.com EDWARD, It. & I. For appointing Saturday, August 9th, a Bank Whereas by Our Royal Proclamation, bearing Iloliday and a Public Holiday. date the 10th day of December last, We did (amongst other things) publish and declare Our EDWARD, R. & I. Royal intention to celebrate the Solemnity of Our Royal Coronation and of the Coronation of We, considering that it is desirable that Satur Our dearly-beloved Consort the Queen upon day, the 9th day of August next, being the occasion Thursday, the 26th day of June, at Our Palace of the Solemnity of Our Royal Coronation, should at Westminster; and whereas We were con be observed as a Rank Holiday and as a Public strained to adjourn the said Solemnity to a day in August thereafter to be determined, We do Holiday throughout the United Kingdom, and in now by this. Our Royal Proclamation, give pursuance of the provisions of “ The Bank notice that W e liave resolved, by the favour and Holidays Act, 1871,” “ The Bank Holidays blessing of Almighty God, to celebrate the said Extension Act, 1875,” “ The Customs Con Solemnity upon Saturday, the 9th day of solidation Act, 1876,” and “ The Revenue Offices August next; and We do hereby strictly charge (Scotland) Holidays Act, 1880,” Do hereby, all Our loving subjects whom it may concern, that all persons of what -

The Times History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902;

aia of The War in South Africa of The War in South Africa 1899-1902 Edited by L. S. Amery Fellow of All Souls With many Photogravure and other Portraits, Maps and Battle Plans Vol. VII Index and Appendices LONDON SAMPSON Low, MARSTON AND COMPANY, LTD. loo, SOUTHWARK STREET, S.E. 1909 LONDON : PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED, DUKE STREET, STAMFORD STREET, S.E., AND GREAT WINDMILL STREET, W PREFACE THE various appendices and the index which make up the present volume are the work of Mr. G. P. Tallboy, who has acted as secretary to the History for the last seven years, and whom I have to thank not only for the labour and research comprised in this volume, but for much useful assistance in the past. The index will, I hope, prove of real service to students of the war. The general principles on which it has been compiled are those with which the index to The Times has familiarized the public. The very full bibliography which Mr. Tallboy has collected may give the reader some inkling of the amount of work involved in the composition of this history. I cannot claim to have actually read all the works comprised in the list, though I think there are comparatively few among them that have not been consulted. On the other hand the list does not include the blue-books, despatches, magazine and newspaper articles, and, above all, private diaries, narratives and notes, which have formed the real bulk of my material. L. S. AMERY. CONTENTS APPENDIX I PAGE. -

Transnational Corporations and the South African Military-Industrial Complex

Transnational Corporations and the South African Military-Industrial Complex http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1979_26 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Transnational Corporations and the South African Military-Industrial Complex Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 24/79 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid; Seidman, Ann W.; Makgetla, Neva Publisher United Nations, New York Date 1979-09-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1979-00-00 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description Introduction. Transnational corporate investments in the South African military-industrial complex.