The Batlle of Colenso Ebook Prep.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Past Veterinarians in South Africa

PAST VETERINARIANS IN SOUTH AFRICA VOLUME 2 M – Z P J POSTHUMUS BVSc M.B.E. 10th EDITION 123 MAAG, ALFONS (2/7/1866 - 26/1/1933) 7 Born Edinburgh, Germany on 2/7/1886 he graduated f ~~~ the f university in Stuttgart in 1908. In 1914 he came to South, Africa as a Government veterinary Officer under the German Government, but was dismissed from his post when the country was captured by the South African Forces in 1915. From 1915 to 1919 he was ~unemployed as a veterinarian, but greatly assisted with the flu epidemic. For his work in this epidemic he was awarded the Red Cross Medal . In 1922 he, Schmid and Sigwart were appointed by the South West Africa administration and it is interesting to note that these three veterinarians were the only former German officials to be so re-employed. After his appointment he was stationed at Gobabis until his health failed. He died from cancer in his home town in Germany on 26/1/1933. MACDONALD, RODERICK (26/12/1874 - Born in Scotland on 26/12/1874 he qualified as a veterinarian at the university of Ontario Vet. College, Canada in 1891. In 1900 he came to South Africa as a Civil Veterinarian attached to the Army veterinary Department to take part in the Boer War. After the war he joined the volunteer corps i n 1903 and after serving as a trooper in its ranks was promoted to Vety Lieutenant on 15/11/1907 and transferred to the East Rand Mounted Rifles (left wing of the Imperial Light Horse). -

Boer War Association Queensland

Boer War Association Queensland Queensland Patron: Major General Professor John Pearn, AO RFD (Retd) Monumentally Speaking - Queensland Edition Committee Newsletter - Volume 12, No. 1 - March 2019 As part of the service, Corinda State High School student, Queensland Chairman’s Report Isabel Dow, was presented with the Onverwacht Essay Medal- lion, by MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD. The Welcome to our first Queensland Newsletter of 2019, and the messages between Ermelo High School (Hoërskool Ermelo an fifth of the current committee. Afrikaans Medium School), South Africa and Corinda State High School, were read by Sophie Verprek from Corinda State Although a little late, the com- High School. mittee extend their „Compli- ments of the Season‟ to all. MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD, together with Pierre The committee also welcomes van Blommestein (Secretary of BWAQ), laid BWAQ wreaths. all new members and a hearty Mrs Laurie Forsyth, BWAQ‟s first „Honorary Life Member‟, was „thank you‟ to all members who honoured as the first to lay a wreath assisted by LTCOL Miles have stuck by us; your loyalty Farmer OAM (Retd). Patron: MAJGEN John Pearn AO RFD (Retd) is most appreciated. It is this Secretary: Pierre van Blommestein Chairman: Gordon Bold. Last year, 2018, the Sherwood/Indooroopilly RSL Sub-Branch membership that enables „Boer decided it would be beneficial for all concerned for the Com- War Association Queensland‟ (BWAQ) to continue with its memoration Service for the Battle of Onverwacht Hills to be objectives. relocated from its traditional location in St Matthews Cemetery BWAQ are dedicated to evolve from the building of the mem- Sherwood, to the „Croll Memorial Precinct‟, located at 2 Clew- orial, to an association committed to maintaining the memory ley Street, Corinda; adjacent to the Sherwood/Indooroopilly and history of the Boer War; focus being descendants and RSL Sub-Branch. -

Kwazulu-Natal Province Facility, Sub-District and District

KWAZULU-NATAL PROVINCE FACILITY, SUB-DISTRICT AND DISTRICT Facility Posts Period Field of Study Province District Sub-District Facility 2017 Audiologist kz KwaZulu-Natal Province kz Amajuba District Municipality kz Dannhauser Local Municipality kz Dannhauser CHC 1 kz Dannhauser Local Municipality Total 1 kz Newcastle Local Municipality kz Madadeni Hospital 1 kz Newcastle Local Municipality Total 1 kz Amajuba District Municipality Total 2 kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality Sub kz Hlengisizwe CHC 1 kz Tongaat CHC 1 kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality Sub Total 2 kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality Total 2 kz Harry Gwala District Municipality kz Greater Kokstad Local Municipality kz East Griqualand and Usher Memorial Hospital 1 kz Greater Kokstad Local Municipality Total 1 kz Ubuhlebezwe Local Municipality kz Christ the King Hospital 1 kz Ubuhlebezwe Local Municipality Total 1 kz Umzimkhulu Local Municipality kz Rietvlei Hospital 1 kz St Margaret's TB MDR Hospital 1 kz Umzimkhulu Local Municipality Total 2 kz Harry Gwala District Municipality Total 4 kz iLembe District Municipality kz Mandeni Local Municipality kz Sundumbili CHC 1 kz Mandeni Local Municipality Total 1 kz Ndwedwe Local Municipality kz Montebello Hospital 1 kz Ndwedwe Local Municipality Total 1 kz iLembe District Municipality Total 2 kz Ugu District Municipality kz Hibiscus Coast Local Municipality kz Gamalakhe CHC 1 kz Hibiscus Coast Local Municipality Total 1 kz Ugu District Municipality Total 1 kz uMgungundlovu District Municipality -

Included Ten in Glasgow, Three in Edinburgh, and Two in THE

742 60 in the three preceding weeks. These 58 deaths were D.S.O., from the Seconded List, to be Major (dated equal to an annual rate of 1 - 7 per 1000, which was March lst, 1905). Lieutenant R. L. V. Foster is seconded slightly above the mean rate last week from the same for service with the Egyptian Army (dated Jan. 17th, diseases in the 76 large English towns. The fatal cases 1905). Major R. H. Penton, D.S.O., from the Seconded of whooping-cough, which had been 27 in each of the List, to be Major (dated March lst, 1905). two preceding weeks, increased last week to 31, of which 22 occurred in Glasgow, two in Edinburgh, two ARMY MEDICAL RESERVE OF OFFICERS. in Greenock, and two in Perth. The fatal cases Surgeon-Major A. A. Watson to be Surgeon-Lieutenant- of diarrhoea, which had been 13, 13, and 16 in the Colonel (dated Feb. 28th, 1905). three further rose to 17 last and preceding weeks, week, A RUSSIAN APPRECIATION OF JAPANESE MEDICINE. included ten in Glasgow, three in and two in Edinburgh, At a of the Vladivostock Medical on Aberdeen. The deaths from measles, which had been seven sitting Society and in the two declined last Jan. 20th last Dr. N. V. Kiriloff and Dr. Rontchevski spoke eight preceding weeks, again of medicine and The former week to six, all of which were recorded in Glasgow. The very highly Japanese hygiene. deaths referred to diseases of the in rapidly traced the meteoric emancipation of Japan (where respiratory organs in were Chinese these towns, which had been and 114 in the even 1876 there still 30,000 medical 119, 116, from Chinese medical to 1901 when three preceding weeks, rose again last week to 153, but men) tutelage up no trace of Chinese in museums or in were slightly below the number in the medicine, except corresponding a few could be found over the whole of last year. -

Inauguration Ceremony for the Mayor for Umtshezi Municipality at the Town Hall, Estcourt, on 29 October 2004 at 14H00

1 Speech delivered by Health MEC and Leader of Government Business, Dr Zweli Mkhize at the Inauguration Ceremony for the Mayor for UMtshezi Municipality at the Town Hall, Estcourt, on 29 October 2004 at 14H00. Today is indeed a great day for the people of Estcourt. Today’s inauguration marks the beginning of a new dawn for the communities of Estcourt... We hope the new beginning brings with it closure to a most unpleasant episode in the politics of this area. It is the hope of many people that today’s event marks the beginning of an era in which service delivery, and not self serving, will be paramount in the minds of all the leaders of this area. One has watched with sadness the recent events unfolding in this Municipality, events which culminated with the tragic death of Councillor Stanley Chetty. One had hoped that our country, and our province in particular, had long gone past the tradition of killing people if they do something we do not like, if they belong to a political party that we do not like, but from the events of the past few weeks it would appear that it is not so. I can say right now that this is unacceptable and that it is a situation that we will not tolerate as the government of this province. The right of freedom of association is enshrined in the Bill of Rights of our Constitution. Section 18 states that everyone has the right to freedom of association. Section 19 (1) of the Bill of Rights further states that: Every citizen is free to make political choices, which include the right a. -

Cultural Heritage Impact Assessment of the Proposed L20 Extension Geluksburg Area, Okahlamba Local Municiality, Kwazulu-Natal

CULTURAL HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE PROPOSED L20 EXTENSION GELUKSBURG AREA, OKAHLAMBA LOCAL MUNICIALITY, KWAZULU-NATAL. For: Hanslab (PTY) Ltd Frans E Prins, MA (Archaeology) P.O. Box 947 Howick 3290 9 July 2017 Cell: 0834739657 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: 0867636380 2 L20 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE PROJECT ........................................... 2 2 BACKGROUND TO ARCHAEOLOGICAL HISTORY OF AREA .......................... 7 2.1.1 THE EARLY STONE AGE .................................................................................. 8 Living Heritage – Wilderness .................................................................................. 13 3 BACKGROUND INFORMATION OF THE SURVEY ........................................... 15 3.1 Methodology ............................................................................................... 15 3.2 Restrictions encountered during the survey ................................................ 16 3.2.1 Visibility ................................................................................................... 16 3.2.2 Disturbance. ............................................................................................ 16 3.3 Details of equipment used in the survey ...................................................... 16 4 DESCRIPTION OF SITES AND MATERIAL OBSERVED ................................... 17 4.1 Locational data ........................................................................................... 17 4.2 Description of the general -

Remembering the Estcourt – Weenen Line 1906

REMEMBERING THE ESTCOURT – WEENEN LINE 1906 – 1983 Bruno Martin Published by the RAILWAY HISTORY SOCIETY, an interest group of the Railway Society of Southern Africa (Natal Branch) Founded 1960 “Travelling on this little train of the thorn country is a real experience. It is certainly the only train in the world which gives the right of way to pythons. The inoffensive reptiles are common in the surrounding bush and the train always does its best to stop and allow them to cross the line. Numerous rock rabbits and various antelopes also have their homes along the track.” - TV Bulpin, Treasure of Travels Series, 5: Johannesburg to Durban, 1973. NGG13 no. 78 about to leave Weenen for Estcourt on 3 March 1979, with Driver Billy Bester in discussion. Photo: Don Baker More than a quarter of a century has passed since the narrow-gauge railway between Estcourt and Weenen was closed. The last revenue-earning service departed unceremoniously from Weenen station on Wednesday afternoon, 31 August 1983. On Monday, 5 September, the remaining goods wagons were retrieved from Weenen and the very last working was for weed spraying on Saturday, 5 October. CONTENTS Setting the Scene Page 3 Survey and Construction 3 Stations, Halts and Sidings 5 Water Supplies 5 List of Bridges 5 Permanent Way 6 Opening and Commencement of Service 6 Original Stations and Halts 6 Later Additions 6 Train Schedules 7 Motive Power 8 Mr J. Billy Bester 9 Map of the Route 10 The Final Years 12 Closure 14 Appendix : A few details of the Rolling Stock 18 References 20 - 2 - SETTING THE SCENE While South Africa’s standard for main line construction was set to a modest three-and-a-half feet (1 067 millimetres) gauge, there were instances where the cost of constructing that gauge was considered too high and the width between the rails was reduced even further. -

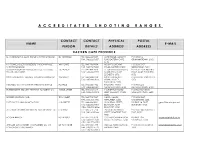

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Tuc6 - Colenso

Printed on 4/12/2013 (version 9) TUc6 - Colenso Bioresource Programme A natural resources classification system for KwaZulu-Natal Disclaimer: All information relating to the Bioresource Classification of KwaZulu-Natal must be regarded as a first approximation. While every reasonable effort has been made by the authors to obtain objective and realistic results, neither they nor the Department of Agriculture and Environmental Affairs of KwaZulu-Natal make any warranty, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in reports relating to the Bioresource Program. Note: The parameters which follow apply to the Bioresource Unit (BRU) as a whole and may not necessarily reflect localized conditions of any particular farm or area within the BRU. References: 1. Camp, K.G.T. 1995. The Bioresource Units of KwaZulu-Natal. Cedara Report N/A/95/32. KZN Department of Agriculture. Pietermaritzburg. 2. Camp, K.G.T. 1999. Guide to the use of the Bioresource Programme. Cedara Report No N/A/99/1. KZN Department of Agriculture. Pietermaritzburg. 3. Camp, K.G.T. 1999. The Bioresource Groups of KwaZulu-Natal : Tall Grassveld including BRG 12 : Moist Tall Grassveld BRG 13 : Dry Tall Grassveld BRG 14 : Sour Sandveld BRG 15 : Moist Lowland Tall Grassveld BRG 16 : Dry Lowland Tall Grassveld Cedara Report No. N/A/99/15. KZN Department of Agriculture. Pietermaritzburg. 4. Smith,B. 2006. The Farming Handbook. University of KwaZulu-Natal Press. 5. Prof. Schultze, R.E. South African Atlas of Climatology and Agrohydrology. 6. Memoirs on the Agricultural resources of South Africa. -

The Canterbury Association

The Canterbury Association (1848-1852): A Study of Its Members’ Connections By the Reverend Michael Blain Note: This is a revised edition prepared during 2019, of material included in the book published in 2000 by the archives committee of the Anglican diocese of Christchurch to mark the 150th anniversary of the Canterbury settlement. In 1850 the first Canterbury Association ships sailed into the new settlement of Lyttelton, New Zealand. From that fulcrum year I have examined the lives of the eighty-four members of the Canterbury Association. Backwards into their origins, and forwards in their subsequent careers. I looked for connections. The story of the Association’s plans and the settlement of colonial Canterbury has been told often enough. (For instance, see A History of Canterbury volume 1, pp135-233, edited James Hight and CR Straubel.) Names and titles of many of these men still feature in the Canterbury landscape as mountains, lakes, and rivers. But who were the people? What brought these eighty-four together between the initial meeting on 27 March 1848 and the close of their operations in September 1852? What were the connections between them? In November 1847 Edward Gibbon Wakefield had convinced an idealistic young Irishman John Robert Godley that in partnership they could put together the best of all emigration plans. Wakefield’s experience, and Godley’s contacts brought together an association to promote a special colony in New Zealand, an English society free of industrial slums and revolutionary spirit, an ideal English society sustained by an ideal church of England. Each member of these eighty-four members has his biographical entry. -

The Psychological Impact of Guerrilla Warfare on the Boer Forces During the Anglo-Boer War

University of Pretoria etd - McLeod AJ (2004) THE PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACT OF GUERRILLA WARFARE ON THE BOER FORCES DURING THE ANGLO-BOER WAR by ANDREW JOHN MCLEOD Submitted as partial requirement for the degree DOCTOR PHILOSOPHIAE (HISTORY) in the Faculty of Human Sciences University of Pretoria Pretoria 2004 Supervisor : Prof. F. Pretorius Co-supervisor : Prof. J.B. Schoeman University of Pretoria etd - McLeod AJ (2004) Abstract of: “The psychological impact of guerrilla warfare on the Boer forces during the Anglo- Boer War” The thesis is based on a multi disciplinary study involving both particulars regarding military history and certain psychological theories. In order to be able to discuss the psychological experiences of Boers during the guerrilla phase of the Anglo-Boer War, the first chapters of the thesis strive to provide the required background. Firstly an overview of the initial conventional phase of the war is furnished, followed by a discussion of certain psychological issues relevant to stress and methods of coping with stress. Subsequently, guerrilla warfare as a global concern is examined. A number of important events during the transitional stage, in other words, the period between conventional warfare and total guerrilla warfare, are considered followed by the regional details concerning the Boers’ plans for guerrilla warfare. These details include the ecological features, the socio-economic issues of that time and military information about the regions illustrating the dissimilarity and variety involved. In the chapters that follow the focus is concentrated on the psychological impact of the guerrilla war on the Boers. The wide range of stressors (factors inducing stress) are arranged according to certain topics: stress caused by military situations; stress caused by the loss of infrastructure in the republics; stress caused by environmental factors; stress arising from daily hardships; stress caused by anguish and finally stressors prompted by an individuals disposition. -

Black & White Illustrated Budget

angloboerwar.com MAJOR-GENERAL HENRY JOHN THORNTON HILDYARD, C.B.. Warren's successor in the command of the Fifth Division, which has done such splendid work under him in driving the Boers out of Natal, is in his fifty-fourth year, and, like French, tried the sea first ; for he was educated at the Royal Naval Academy at Gosport, entering' the Na\T in 1859. Eight years later, however, he joined the Army, and in 1876 he became a captain in the Highland Light Infantry. He served with distinction in the Egyptian Expedition of 1882, being present at Kassassin and Tel-el-Kebir, receiving several decorations and being made a Brevet-Lieut. -Colonel. Then he became D.A.A.G. , and A.A.G. at headquarters, A.A.G. at Aldershot, and, from 1893 to 1898, Commandant of the Staff College, a capacity in which his versatility enabled him to be no less successful than he was previously on the field of battle. In '98 he took up the command of the Third Brigade at Aldershot, going to the front last year with the Second Infantry Brigade, whose battalions were among the first troops to embark. 290 BLACK AND WHITE BUDGET Juke o, 1900 NOW READY. VOLUMES I. AND ir. BLACK AND WHITE BUDGET, Bound in handsome embossed cloth covers, with gilt letters, Price ds. Post free, 6s. 3d. CLOTH COVERS FOR BINDING BLACKangloboerwar.comAND WHITE BUDGET Price IS. 6d. Post free is. 8d. This Case is made to contain the extra Number THE QUEEN IN IRELAND. ALL BACK NUMBERS ARE NOW IN PRLNZ AND CAN BE OBTAINED FROM ' ALL NEWSAGENTS AND BOOKSTALLS.