Western Massachuses Emergency Communicaons Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

United States of America Before the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BEFORE THE FEDERAL ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION Iberdrola, S.A. ) Avangrid, Inc. ) Avangrid Networks, Inc. ) PNM Resources, Inc. ) Public Service Company of New ) Docket No. EC21-___-000 Mexico ) NMRD Data Center II, LLC ) NMRD Data Center III, LLC ) New Mexico PPA Corporation ) APPLICATION FOR AUTHORIZATION OF TRANSACTION UNDER SECTION 203 OF THE FEDERAL POWER ACT AND REQUESTS FOR SHORTENED COMMENT PERIOD, EXPEDITED ACTION, WAIVERS OF FILING REQUIREMENTS AND CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT OF WORKPAPERS Pursuant to Sections 203(a)(1) and (a)(2) of the Federal Power Act (“FPA”)1 and Part 33 of the Rules and Regulations of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (“FERC” or the “Commission”),2 Iberdrola, S.A. (“Iberdrola”), Avangrid, Inc. (“Avangrid”) and Avangrid Networks, Inc. (“Networks” and together with Iberdrola and Avangrid, the “Avangrid Applicants”) and PNM Resources, Inc. (“PNMR”), on behalf of its public utility subsidiaries, Public Service Company of New Mexico (“PNM”), NMRD Data Center II, LLC (“NMRD II”), NMRD Data Center III, LLC (“NMRD III”), and New Mexico PPA Corporation (“NMPC”) (and together with PNMR, the “PNMR Applicants”) (collectively, the Avangrid Applicants and the PNMR Applicants are referred to herein as, the “Applicants”), hereby submit this application (“Application”) requesting Commission authorization for the disposition of jurisdictional facilities resulting from a proposed transaction whereby NM Green Holdings, Inc. (“NM Green 1 16 U.S.C. § 824b(a)(1) and (a)(2). 2 18 C.F.R. pt. 33 (2020). Holdings”), a direct and wholly-owned subsidiary of Avangrid created solely for the purpose of effectuating the Proposed Transaction, will merge with and into PNMR, with PNMR as the surviving entity of the merger (as described further herein, the “Merger Transaction”) and the subsequent transfer of PNMR to Networks, a direct, wholly-owned subsidiary of Avangrid (collectively referred to herein as, the “Proposed Transaction”). -

Massachusetts Department of Early Education and Care

Massachusetts Department of Early Education and Care Annual Legislative Report FY2012 Submitted February 15, 2012 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Glossary of Acronyms Page 8 EEC: Purpose, Function and Goals Page 10 Introduction Page 11 Submission of Annual Report Page 14 2012 Context Page 15 Conclusion of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) Funding Work of the Board of Early Education and Care Massachusetts Wins Race to the Top - Early Learning Challenge Grant Board of Early Education and Care Page 20 EEC Board Votes 2011 EEC Board Retreat Organizational Framework Page 23 Budget Page 24 Strategic Direction: Quality Page 25 Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS) Supporting Quality in Infant and Toddler Settings Head Start Alignment of Standards Alignment of Preschool Curriculum Frameworks with the Common Core Standards Early Learning Guidelines for Infants and Toddlers Professional Development System Professional Development Programs FY2012 Educator and Provider Support Institutions of Higher Education Mapping Project State Supported Efforts Supporting Improvements in Physical Environments Resources for Military Families Screening and Assessment 2 Massachusetts Kindergarten Entry Assessment (MKEA) Kindergarten Readiness Assessment Model Design and Pilot Project FY2011/12 Assessment Supports State Supported Family Education Resources Coordinated Family and Community Engagement (CFCE) Grant - Refining Goals FY2012 Universal Pre-Kindergarten (UPK) Program FY2012 Universal Pre-Kindergarten (UPK) Program / FY2013 Planning Grantee -

FY 2004 AM and FM Radio Station Regulatory Fees

FY 2004 AM and FM Radio Station Regulatory Fees Call Sign Fac. ID. # Service Class Community State Fee Code Fee Population KA2XRA 91078 AM D ALBUQUERQUE NM 0435$ 425 up to 25,000 KAAA 55492 AM C KINGMAN AZ 0430$ 525 25,001 to 75,000 KAAB 39607 AM D BATESVILLE AR 0436$ 625 25,001 to 75,000 KAAK 63872 FM C1 GREAT FALLS MT 0449$ 2,200 75,001 to 150,000 KAAM 17303 AM B GARLAND TX 0480$ 5,400 above 3 million KAAN 31004 AM D BETHANY MO 0435$ 425 up to 25,000 KAAN-FM 31005 FM C2 BETHANY MO 0447$ 675 up to 25,000 KAAP 63882 FM A ROCK ISLAND WA 0442$ 1,050 25,001 to 75,000 KAAQ 18090 FM C1 ALLIANCE NE 0447$ 675 up to 25,000 KAAR 63877 FM C1 BUTTE MT 0448$ 1,175 25,001 to 75,000 KAAT 8341 FM B1 OAKHURST CA 0442$ 1,050 25,001 to 75,000 KAAY 33253 AM A LITTLE ROCK AR 0421$ 3,900 500,000 to 1.2 million KABC 33254 AM B LOS ANGELES CA 0480$ 5,400 above 3 million KABF 2772 FM C1 LITTLE ROCK AR 0451$ 4,225 500,000 to 1.2 million KABG 44000 FM C LOS ALAMOS NM 0450$ 2,875 150,001 to 500,000 KABI 18054 AM D ABILENE KS 0435$ 425 up to 25,000 KABK-FM 26390 FM C2 AUGUSTA AR 0448$ 1,175 25,001 to 75,000 KABL 59957 AM B OAKLAND CA 0480$ 5,400 above 3 million KABN 13550 AM B CONCORD CA 0427$ 2,925 500,000 to 1.2 million KABQ 65394 AM B ALBUQUERQUE NM 0427$ 2,925 500,000 to 1.2 million KABR 65389 AM D ALAMO COMMUNITY NM 0435$ 425 up to 25,000 KABU 15265 FM A FORT TOTTEN ND 0441$ 525 up to 25,000 KABX-FM 41173 FM B MERCED CA 0449$ 2,200 75,001 to 150,000 KABZ 60134 FM C LITTLE ROCK AR 0451$ 4,225 500,000 to 1.2 million KACC 1205 FM A ALVIN TX 0443$ 1,450 75,001 -

Broadcast Applications 12/4/2013

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 28128 Broadcast Applications 12/4/2013 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE TX BALH-20130701ADA DKTDK 26146 SUSQUEHANNA RADIO CORP. Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended E 104.1 MHZ TX , SANGER From: SUSQUEHANNA RADIO CORP. To: WHITLEY MEDIA LLC Form 314 Dismissed as inadvertently accepted for filing (DA 13-1938). Petition for Reconsideration Filed 09/24/2013 by SUSQUEHANNA RADIO CORP. Petition for Reconsideration Dismissed 10/18/2013 per applicant's request - no letter sent Supplement Filed 09/27/2013 by SUSQUEHANNA RADIO CORP. Motion to Withdraw Filed 10/17/2013 by SUSQUEHANNA RADIO CORP. Petition for Reconsideration Filed 10/21/2013 by Whitley Media, LLC and North Texas Radio Group, L.P. Motion to Dismiss Filed 10/31/2013 by First IV Media, Inc. Supplement Filed 11/12/2013 by Whitley Media, LLC and North Texas Radio Group, L.P. Opposition Filed 11/13/2013 by Whitley Media, LLC and North Texas Radio Group, L.P. Reply Filed 11/25/2013 by First IV Media, Inc. Page 1 of 56 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. -

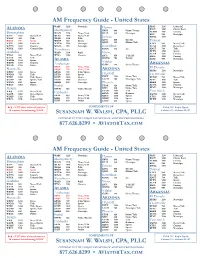

AM Radio Guide Version 1.4 For

AM Frequency Guide - United States LABAMA WABF 1220 Nostalgia Homer KISO 1230 Urban AC A KSLX 1440 Classic Rock Montgomery KBBI 890 News/Variety KCWW 1580 Country Birmingham WACV 1170 News/Talk KGTL 620 Nostalgia KOY 550 Nostalgia WAPI 1070 News/Talk WLWI 1440 News/Talk KMYL 1190 WERC 960 Talk WIQR 1410 Talk Juneau WJOX 690 Sports WMSP 740 Sports KINY 800 Hot AC Tucson WJLD 1400 Urban AC WTLM 1520 Nostalgia KJNO 630 Oldies/Talk KTKT 990 News/Talk WFHK 1430 Country WNZZ 950 Nostalgia Ketchikan KUAT 1550 News/Jazz WPYK 1010 Country Olds Tuscaloosa KTKN 930 AC KNST 790 Talk KFFN 1490 Sports Gadsden WAJO 1310 R&B Nome KCUB 1290 Country WNSI 810 News/Talk WVSA 1380 Country KICY 850 Talk/AC KHIL 1250 Country WAAX 570 Talk KNOM 780 Variety KSAZ 580 Nostalgia WHMA 1390 Sports ALASKA WZOB 1250 Country Valdez ARKANSAS WGAD 1350 Oldies Anchorage KCHU 770 News/Variety KENI 650 News/Talk El Dorado Huntsville KFQD 750 News/Talk ARIZONA KDMS 1290 Nostalgia WBHP 1230 News KBYR 700 Talk/Sports WVNN 770 Talk KTZN 550 Sports Flagstaff Fayetteville WTKI 1450 Talk/Sports KAXX 1020 Sports KYET 1180 News/Talk KURM 790 News/Talk WUMP 730 Sports/Talk KASH 1080 Classical KAZM 780 Nostalgia/Talk KFAY 1030 Talk WZNN 620 Sports KHAR 590 Nostalgia Phoenix KREB 1390 Sports WKAC 1080 Oldies Bethel KTAR 620 News/Talk KUOA 1290 Country KESE 1190 Nostalgia Mobile KYUK 640 News/Variety KFYI 910 News/Talk WKSJ 1270 News/Talk KXAM 1310 Talk Fort Smith WABB 1480 News/Sports Fairbanks KFNN 1510 Business KWHN 1320 News/Talk WHEP 1310 Talk KFAR 660 News/Talk KDUS 1060 Sports KTCS 1410 Country KIAK 970 News/Talk WBCA 1110 Country Olds KGME 1360 Sports KFPW 1230 Nostalgia KCBF 820 Oldies KMVP 860 Sports Red = FCC clear channel stations COMPLIMENTS OF AM & HF Radio Guide & stations broadcasting 50 KW SUSANNAH W. -

The Town of Ware Hazard Mitigation Plan

The Town of Ware Hazard Mitigation Plan Adopted by the Ware Select Board on __________ The Ware Hazard Mitigation Committee and Pioneer Valley Planning Commission 60 Congress Street Springfield, MA 01104 (413) 781‐6045 www.pvpc.org This project was funded by a grant received from the Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency (MEMA) and the Massachusetts Department of Conservation Services (formerly the Department of Environmental Management) Acknowledgements The Ware Select Board extends special thanks to the Ware Hazard Mitigation Planning Committee as follows: Ed Wloch, Deputy Fire Chief Thomas Coulombe, Fire Chief Karen Cullen, Director of Planning and Community Development Stuart Beckley, Town Manager The Ware Select Board offers thanks to the Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency (MEMA) for developing the Massachusetts Hazard Mitigation Plan which served as a model for this plan. In addition, special thanks are extended to the staff of the Pioneer Valley Planning Commission for professional services, process facilitation and preparation of this document. The Pioneer Valley Planning Commission Catherine Ratté, Principal Planner/Co‐Project Manager Josiah Neiderbach, Planner/Co‐Project Manager Todd Zukowski, Principal Planner/GIS‐Graphics Section Head Jake Dolinger, GIS Specialist Brian Conboy, Intern 1: Planning Process 1 Introduction 1 Hazard Mitigation Committee 2 Participation by Public and Neighboring Communities 3 Select Board Meeting 3 2: Local Profile 4 Community Setting 4 Development 4 Infrastructure 6 Natural Resources -

Franklin County Regional Shelter Plan

FRANKLIN COUNTY REGIONAL SHELTER PLAN June Concept of Operations 2013 Table of Contents Plan Purpose and Authority ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Definitions ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Assumptions .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Participating Municipality Endorsements ...................................................................................................................... 2 Plan Development and Maintenance ............................................................................................................................ 3 Plan Activation ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 Triggers .................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Authority to Request Opening a Regional Shelter: .................................................................................................. 3 Authority to Open the Shelter: ............................................................................................................................... -

Read Winter 2016 Newsletter Part 1

OLISH CENTER NEWSLETTER P OF DISCOVERY AND LEARNING NEW POLISH CENTER GALLERY OF REGIONAL COSTUMES he Polish Center is grateful to Farley’s life. Krystyna was born in 1925 Krystyna Slowikowska Farley, of in the village of Orlopol, Krzemieniec New Britain Connecticut, for the Poland. Her journey to America began with Tdonation of her personal collection of a brutal act of ethnic cleansing of Poles and Polish costumes. Visitors to the museum Jews in her home town of Orlopol, Poland can now see the display of thirty-two (now Ukraine) on February 10, 1940. The costumes on the third floor of the Polish Stachowicz family, Krystyna, her mother Center. and father and four siblings were deported For a country of modest size, traditional to a Soviet slave labor camp in the Ural regional dress of Poland is remarkably rich Mountains in the north of Russia. Packed in number and variety of designs, as well into a single freight car with 60 other as use of color and pattern. The origin of people, the family managed to survive the styles with which we are familiar today to reach its destination 30 days later. Her can be traced primarily to the second half mother did not survive the harsh realities of the 1800s, with just a few which can be of brutal exile while one of her sisters went traced to the end of the eighteenth or the missing, never to be found. mid-twentieth centuries. Siberian exile ended for the Stachow- With the abolishment of serfdom, icz family when Nazi Germany invaded traditional attire grew more expressive and the Soviet Union. -

DX News Serving Medium Wave Dxers Since 1933 Volume 87, No

DX News Serving Medium Wave DXers since 1933 Volume 87, No. 11 ● Feb. 18, 2020 ● (ISSN 0737-1639) Inside this issue . 2 … AM Switch 21 … GYDXA Update 6 … Domestic DX Digest West 22 … LBI 2019 DXPedition 14 … Domestic DX Digest East 31 … Convention Info 19 … International DX Digest 32 … DX Toolbox 21 … Geomagnetic Indices 33 … Musings of the Members Publications: Due to yet another increase in We have just one more biweekly issue coming postage costs, we must increase the rates for AM up and then we’ll switch to every three weeks for Radio Log and NRC Pattern Book when delivered to the next four issues through the spring. So keep Canadian and overseas addresses. The price for your DX reports coming! shipping to U.S. addresses is unchanged. New rates are reflected in this issue. Last Chance for Annual WRTH Raffle: How Volume 87 DXN Schedule would you like a new 2020 W RTH for $13? (I No D’dline Print 16 May 17 May 26 know it was $12 last year, but USPS raised the 12 Feb. 23 Mar. 3 17 June 14 June 23 rates again.) This is for USA members or members 13 Mar. 15 Mar. 24 18 July 12 July 21 that have availability of a U.S. mailing address. 14 Apr. 5 Apr. 14 19 Aug. 16 Aug. 25 Sorry, the cost of postage to Canada and 15 Apr. 26 May 5 20 Sept. 13 Sept. 22 elsewhere is more than the cost of the book! The NRC has 4 copies that will be available Membership Report through this raffle. -

2003-2004 Undergraduate Catalog

SPRINGFIELD COLLEGE 263 Alden Street, Springfield, MA 01109-3797 UNDERGRADUATE CATALOG 2003-2004 Richard B. Flynn (1999), B.S., M.Ed., Ed.D. Robert J. Willey, Jr. (2002), B.S., M.A., Ph.D. President of the College Dean, School of Human Services Jean A. Wyld (2001), B.A., M.S., Ph.D. Francine J. Vecchiolla (1990), B.S., M.S.W., Ph.D. Vice President for Academic Affairs Dean, School of Social Work M. Ben Hogan (2000), B.A., M.S., Ed.D. Mary N. DeAngelo (1984), B.A., M.Ed. Vice President for Student Affairs/Dean of Students Director of Undergraduate Admissions David J. Fraboni (2001), B.S. John W. Wilcox (1970), B.S., M.Ed. Vice President for Institutional Advancement Executive Director of Enrollment Management John L. Mailhot (1988), B.S., M.B.A. Vice President for Administration and Finance Gretchen A. Brockmeyer (1979), B.A., M.S., Ed.D. Associate Vice President for Academic Affairs William J. Considine (1976), B.S., M.S., P.E.D. Dean, School of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation Mary D. Healey (1981), B.S., M.Ed., M.S., Ph.D. Dean, School of Arts, Sciences and Professional Studies Betty L. Mann (1984), B.S., M.Ed., D.P.E. Dean, Graduate Studies INTRODUCTION Founded in 1885, Springfield College is a private, coeducational institution offering undergraduate and graduate programs that reflect its distinctive humanics philosophy—education of the whole person in spirit, mind, and body for leadership in service to humanity. It is world renowned as the Birthplace of Basketball™,a game created by alumnus and professor James Naismith in 1891; as the alma mater of William G. -

Sustaining Community: a New Social, Economic, and Environmental Path for Ware, MA

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses August 2014 Sustaining Community: A New Social, Economic, and Environmental Path for Ware, MA Aviva J. Galaski University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Recommended Citation Galaski, Aviva J., "Sustaining Community: A New Social, Economic, and Environmental Path for Ware, MA" (2014). Masters Theses. 17. https://doi.org/10.7275/5531462 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/17 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SUSTAINING COMMUNITY A NEW SOCIAL, ECONOMIC, AND ENVIRONMENTAL PATH FOR WARE, MA A Thesis Presented by AVIVA J. GALASKI Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE May 2014 Department of Art, Architecture, and Art History SUSTAINING COMMUNITY: A NEW SOCIAL, ECONOMIC, AND ENVIRONMENTAL PATH FOR WARE, MA A Thesis Presented by AVIVA J. GALASKI Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________________ Kathleen Lugosch, Chair _______________________________________ Joseph Krupczynski, Member ____________________________________ William T. Oedel, Department Chair Art, Architecture, and Art History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to the faculty in Architecture, LARP, and BCT for nurturing and challenging me. The knowledge that each of you have imparted to me is evident in this document. Thank you in particular to Joseph and Kathleen for your boundless encouragement.