Water Resource Management: Local Control & Local Solutions a Quick Guide to Groundwater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

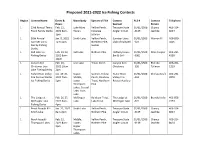

Proposed 2021-2022 Ice Fishing Contests

Proposed 2021-2022 Ice Fishing Contests Region Contest Name Dates & Waterbody Species of Fish Contest ALS # Contact Telephone Hours Sponsor Person 1 23rd Annual Teena Feb. 12, Lake Mary Yellow Perch, Treasure State 01/01/1500 Chancy 406-314- Frank Family Derby 2022 6am- Ronan Kokanee Angler Circuit -3139 Jeschke 8024 1pm Salmon 1 50th Annual Jan. 8, 2022 Smith Lake Yellow Perch, Sunriser Lions 01/01/1500 Warren Illi 406-890- Sunriser Lions 7am-1pm Northern Pike, Club of Kalispell -323 0205 Family Fishing Sucker Derby 1 Bull Lake Ice Feb. 19-20, Bull Lake Nothern Pike Halfway House 01/01/1500 Dave Cooper 406-295- Fishing Derby 2022 6am- Bar & Grill -3061 4358 10pm 1 Canyon Kid Feb. 26, Lion Lake Trout, Perch Canyon Kids 01/01/1500 Rhonda 406-261- Christmas Lion 2022 10am- Christmas -326 Tallman 1219 Lake Fishing Derby 2pm 1 Fisher River Valley Jan. 29-30, Upper, Salmon, Yellow Fisher River 01/01/1500 Chelsea Kraft 406-291- Fire Rescue Winter 2022 7am- Middle, Perch, Rainbow Valley Fire -324 2870 Ice Fishing Derby 5pm Lower Trout, Northern Rescue Auxilary Thompson Pike Lakes, Crystal Lake, Loon Lake 1 The Lodge at Feb. 26-27, McGregor Rainbow Trout, The Lodge at 01/01/1500 Brandy Kiefer 406-858- McGregor Lake 2022 6am- Lake Lake Trout McGregor Lake -322 2253 Fishing Derby 4pm 1 Perch Assault #2- Jan. 22, 2022 Smith Lake Yellow Perch, Treasure State 01/01/1500 Chancy 406-314- Smith Lake 8am-2pm Nothern Pike Angler Circuit -3139 Jeschke 8024 1 Perch Assault- Feb. -

Effects of Ice Formation on Hydrology and Water Quality in the Lower Bradley River, Alaska Implications for Salmon Incubation Habitat

ruses science for a changing world Prepared in cooperation with the Alaska Energy Authority u Effects of Ice Formation on Hydrology and Water Quality in the Lower Bradley River, Alaska Implications for Salmon Incubation Habitat Water-Resources Investigations Report 98-4191 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover photograph: Ice pedestals at Bradley River near Tidewater transect, February 28, 1995. Effects of Ice Formation on Hydrology and Water Quality in the Lower Bradley River, Alaska Implications for Salmon Incubation Habitat by Ronald L. Rickman U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 98-4191 Prepared in cooperation with the ALASKA ENERGY AUTHORITY Anchorage, Alaska 1998 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas J. Casadevall, Acting Director Use of trade names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information: Copies of this report may be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services 4230 University Drive, Suite 201 Box 25286 Anchorage, AK 99508-4664 Denver, CO 80225-0286 http://www-water-ak.usgs.gov CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................... 1 Location of Study Area.................................................. 1 Bradley Lake Hydroelectric Project ....................................... -

Chautauqua County Envirothon Wildlife Review

Chautauqua County Envirothon Wildlife Review • William Printup, Civil Engineering • Wendy Andersen, Permitting Allegheny National Forest Slide 1 Wildlife Learning Objectives For successful completion of the wildlife section, contestants should be able to: 1. Assess suitability of habitat for given wildlife species 2. Identify signs of wildlife 3. Cite examples of food chains based on specific site conditions 4. Analyze/Interpret site factors that limit or enhance population growth, both in the field and with aerial photos 5. Interpret significance of habitat alteration due to human impacts on site 6. Evaluate factors that might upset ecological balance of a specific site 7. Identify wildlife by their tracks, skulls, pelts, etc. 8. Interpret how presence of wildlife serves as an indicator of environmental quality 9. Identify common wildlife food Slide 2 WILDLIFE OUTLINE I. Identification of NYS Species (http://www.dec.ny.gov/23.html) • A. Identify NYS wildlife species by specimens, skins/pelts, pictures, skulls, silhouettes, decoys, wings, feathers, scats, tracks, animal sounds, or other common signs • B. Identify general food habits, habitats, and habits from teeth and/or skull morphology • C. Specific habitats of the above • II. Wildlife Ecology • A. Basic ecological concepts and terminology • B. Wildlife population dynamics • 1) Carrying capacity • 2) Limiting factors • C. Adaptations of wildlife • 1) Anatomical, physiological and/or behavioral • D. Biodiversity • 1) Genetic, species, ecosystem or community Slide 3 Outline Continued.. • III. Wildlife Conservation and Management • A. Common management practices and methods • 1) Conservation • 2) Protection • 3) Enhancement • B. Hunting regulations • C. Land conflicts with wildlife habitat needs • D. Factors influencing management decisions • 1) Ecological • 2) Financial •3) Social • E. -

The Federal Role in Groundwater Supply

The Federal Role in Groundwater Supply Updated May 22, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45259 The Federal Role in Groundwater Supply Summary Groundwater, the water in aquifers accessible by wells, is a critical component of the U.S. water supply. It is important for both domestic and agricultural water needs, among other uses. Nearly half of the nation’s population uses groundwater to meet daily needs; in 2015, about 149 million people (46% of the nation’s population) relied on groundwater for their domestic indoor and outdoor water supply. The greatest volume of groundwater used every day is for agriculture, specifically for irrigation. In 2015, irrigation accounted for 69% of the total fresh groundwater withdrawals in the United States. For that year, California pumped the most groundwater for irrigation, followed by Arkansas, Nebraska, Idaho, Texas, and Kansas, in that order. Groundwater also is used as a supply for mining, oil and gas development, industrial processes, livestock, and thermoelectric power, among other uses. Congress generally has deferred management of U.S. groundwater resources to the states, and there is little indication that this practice will change. Congress, various states, and other stakeholders recently have focused on the potential for using surface water to recharge aquifers and the ability to recover stored groundwater when needed. Some see aquifer recharge, storage, and recovery as a replacement or complement to surface water reservoirs, and there is interest in how federal agencies can support these efforts. In the congressional context, there is interest in the potential for federal policies to facilitate state, local, and private groundwater management efforts (e.g., management of federal reservoir releases to allow for groundwater recharge by local utilities). -

Paani Foundation Is a Not-For-Profit Organization Which Has Been the Brainchild of Aamir Khan and Kiran Rao

ANNUAL REPORT PAANI FOUNDATION’S ACTIVITIES IN 2016 Background: Paani Foundation is a not-for-profit organization which has been the brainchild of Aamir Khan and Kiran Rao. The organization was registered in early 2016 in order to work towards creating a drought-free Maharashtra. The idea originated from the television show Satyameva Jayate which was being anchored by Aamir Khan , addressing various social issues . One of the crucial issues that strongly came up was the water scarcity in Maharashtra which was mainly due to the topographical pattern of large areas in existence which are drought prone and face serious lack of rain every year. India is classified globally as a water-adequate nation. It has neither abundance nor scarcity. It has enough for its needs. Yet, increasingly, more and more people do not have water to drink, more and more farmers face drought and starvation, and more and more industries shut down or cannot grow because of a shortage of water. The reason for the Water Crisis: The crisis is largely man-made and has four key causes: 1. Pollution: We have polluted our lakes and rivers. 2. Over-Exploitation: We have recklessly pumped out ground water without bothering to recharge the groundwater table resulting in a catastrophic fall in its level. 3. Irrational Water Management: Can be described well with the example of highly water-intensive sugarcane cultivation in drought-prone areas. 4. Climate Change: Rainfall is getting compressed in both space and time. The number of rain days is decreasing. Rainfall is concentrated in small areas with vast land masses subject to drought. -

Using the Water Quality Index (WQI), and the Synthetic Pollution Index

Sains Malaysiana 49(10)(2020): 2383-2401 http://dx.doi.org/10.17576/jsm-2020-4910-05 Using the Water Quality Index (WQI), and the Synthetic Pollution Index (SPI) to Evaluate the Groundwater Quality for Drinking Purpose in Hailun, China (Penggunaan Indeks Kualiti Air (WQI) dan Indeks Pencemaran Sintetik (SPI) untuk Menilai Kualiti Air Bawah Tanah untuk Tujuan Minuman di Hailun, China) TIAN HUI*, DU JIZHONG, SUN QIFA, LIU QIANG, KANG ZHUANG & JIN HONGTAO ABSTRACT Due to the impact of human agricultural production, climate and environmental changes. The applicability of groundwater for drinking purposes has attracted widespread attention. In order to quantify the hydrochemical characteristics of groundwater in Hailun and evaluate its suitability for assessing water for drinking purposes, 77 shallow groundwater samples and 57 deep groundwater samples were collected and analyzed. The results show that deep groundwater in - aquifers in the study area is weakly alkaline, while that in shallow is acidic. The abundance is in the order HCO3 > - 2- 2+ + 2+ Cl > SO4 for anions, and Ca > Na > Mg for cations. Groundwater chemical type were dominated by HCO3-Ca, HCO3-Ca• Mg, and HCO3-Ca• Na. Correlation analysis (CA) and Durov diagram showed that rock weathering and dissolution, human activities, and the hydraulic connection between shallow and deep water are the main reasons affecting the chemical composition of water in Helen. The analysis of water samples based on the WQI model showed that about 23.37, 23.37, 32.46, 12.98, and 7.79% of the shallow groundwater samples were excellent, good, poor, very poor, and unsuitable for drinking purposes, respectively, and that 61.40, 30.90, 5.26, 1.75, and 1.75% of the deep groundwater samples were excellent, good, poor, very poor, and unsuitable for drinking purposes, respectively. -

“Mining” Water Ice on Mars an Assessment of ISRU Options in Support of Future Human Missions

National Aeronautics and Space Administration “Mining” Water Ice on Mars An Assessment of ISRU Options in Support of Future Human Missions Stephen Hoffman, Alida Andrews, Kevin Watts July 2016 Agenda • Introduction • What kind of water ice are we talking about • Options for accessing the water ice • Drilling Options • “Mining” Options • EMC scenario and requirements • Recommendations and future work Acknowledgement • The authors of this report learned much during the process of researching the technologies and operations associated with drilling into icy deposits and extract water from those deposits. We would like to acknowledge the support and advice provided by the following individuals and their organizations: – Brian Glass, PhD, NASA Ames Research Center – Robert Haehnel, PhD, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers/Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory – Patrick Haggerty, National Science Foundation/Geosciences/Polar Programs – Jennifer Mercer, PhD, National Science Foundation/Geosciences/Polar Programs – Frank Rack, PhD, University of Nebraska-Lincoln – Jason Weale, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers/Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory Mining Water Ice on Mars INTRODUCTION Background • Addendum to M-WIP study, addressing one of the areas not fully covered in this report: accessing and mining water ice if it is present in certain glacier-like forms – The M-WIP report is available at http://mepag.nasa.gov/reports.cfm • The First Landing Site/Exploration Zone Workshop for Human Missions to Mars (October 2015) set the target -

Controlling Groundwater Pollution from Petroleum Products Leaks

Environmental Toxicology III 91 Controlling groundwater pollution from petroleum products leaks M. S. Al-Suwaiyan Civil Engineering Department, King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, Saudi Arabia Abstract Groundwater is the main source of potable water in many communities. This source is susceptible to pollution by toxic organic compounds resulting from the accidental release of petroleum products. A petroleum product like gasoline is a mixture of many organic compounds that are toxic at different degrees to humans. These various compounds have different characteristics that influence the spread and distribution of plumes of the various dissolved toxins. A compositional model utilizing properties of organics and soil was developed and used to study the concentration of benzene, toluene and xylene (BTX) in leachate from a hypothetical site contaminated by BTX. Modeling indicated the high and variable concentration of contaminants in leachate and its action as a continuous source of groundwater pollution. In a recent study, the status of underground fuel storage tanks in eastern Saudi Arabia and the potential for petroleum leaks was evaluated indicating the high potential for aquifer pollution. As a result of such discussion, it is concluded that more effort should be directed to promote leak prevention through developing proper design regulations and installation guidelines for new and existing service stations. Keywords: groundwater pollution, petroleum products, dissolved contaminants, modelling contaminant transport. 1 Introduction Water covers about 73% of our planet with a huge volume of 1.4 billion cubic kilometers most of which is saline. According to the water encyclopedia [1], only about 3-4% of the total water is fresh. -

GOALS for CANON ENVIROTHON CURRICULUM to Develop A

GOALS FOR CANON ENVIROTHON CURRICULUM To develop a teacher friendly, hands on natural resources curriculum. To provide activities and lessons for teams new to the Envirothon, while challenging experienced teams. Use of these curriculum materials will result in: . •Increased Envirothon participation at the local, regional, and State/Provincial levels. •Increased team scores at the Canon Envirothon Contest in the four natural resource categories: soils and land use, aquatic ecology, forestry, and wildlife. Canon Envirothon SOILS/LAND USE CORE ACTIVITY OUTLINE The key points for each Envirothon topic are “fleshed out” into core activities. • Each of the key points is included in one or more of the core activities. • Each core activity contains extended activities, as well as the top resources and professional contacts. Key vocabulary words are also included. • The National Science Standards suggest evaluations for each activity should encourage the students to process the data they collect during the activity, and provide solutions based on the data. This ties each activity into the issues portion of the contest. • Evaluation is based on the information provided for each core activity and from the data students collect. This allows students to make educated decisions and create solutions for the key issues. • Core activities will be evaluated using a performance based assessment. Soils/Land Use Curriculum Soils/Land Use Envirothon Key Points 1S Recognize soil as an important and dynamic resource. 2S Recognize and understand the features of a soil profile. 3S Describe basic soil properties and soil formation factors. 4S Understand the origin of soil parent materials. 5S Identify soil constituents (clay, organic matter, sand and silt). -

Reference: Groundwater Quality and Groundwater Pollution

PUBLICATION 8084 FWQP REFERENCE SHEET 11.2 Reference: Groundwater Quality and Groundwater Pollution THOMAS HARTER is UC Cooperative Extension Hydrogeology Specialist, University of California, Davis, and Kearney Agricultural Center. roundwater quality comprises the physical, chemical, and biological qualities of UNIVERSITY OF G ground water. Temperature, turbidity, color, taste, and odor make up the list of physi- CALIFORNIA cal water quality parameters. Since most ground water is colorless, odorless, and Division of Agriculture without specific taste, we are typically most concerned with its chemical and biologi- and Natural Resources cal qualities. Although spring water or groundwater products are often sold as “pure,” http://anrcatalog.ucdavis.edu their water quality is different from that of pure water. In partnership with Naturally, ground water contains mineral ions. These ions slowly dissolve from soil particles, sediments, and rocks as the water travels along mineral surfaces in the pores or fractures of the unsaturated zone and the aquifer. They are referred to as dis- solved solids. Some dissolved solids may have originated in the precipitation water or river water that recharges the aquifer. A list of the dissolved solids in any water is long, but it can be divided into three groups: major constituents, minor constituents, and trace elements (Table 1). The http://www.nrcs.usda.gov total mass of dissolved constituents is referred to as the total dissolved solids (TDS) concentration. In water, all of the dissolved solids are either positively charged ions Farm Water (cations) or negatively charged ions (anions). The total negative charge of the anions always equals the total positive charge of the cations. -

The Conservation and Sustainable Use of Freshwater Resources in West Asia, Central Asia and North Africa

IUCN-WESCANA Water Publication The Conservation and Sustainable Use of Freshwater Resources in West Asia, Central Asia and North Africa The 3rd IUCN World Conservation Congress Bangkok, Kingdom of Thailand, November 17-25, 2004 IUCN Regional Office for West/Central Asia and North Africa Kuwait Foundation For The Advancement of Sciences The World Conservation Union 1 2 3 The Conservation and Sustainable Use of Freshwater Resources in West Asia, Central Asia and North Africa The 3rd IUCN World Conservation Congress Bangkok, Kingdom of Thailand, November 17-25, 2004 IUCN Regional Office for West/Central Asia and North Africa Kuwait Foundation 2 For The Advancement of Sciences The World Conservation Union 3 4 5 Table of Contents The demand for freshwater resources and the role of indigenous people in the conservation of wetland biodiversity Mehran Niazi.................................................................................. 8 Managing water ecosystems for sustainability and productivity in North Africa Chedly Rais................................................................................... 17 Market role in the conservation of freshwater biodiversity in West Asia Abdul Majeed..................................................................... 20 Water-ecological problems of the Syrdarya river delta V.A. Dukhovny, N.K. Kipshakbaev,I.B. Ruziev, T.I. Budnikova, and V.G. Prikhodko............................................... 26 Fresh water biodiversity conservation: The case of the Aral Sea E. Kreuzberg-Mukhina, N. Gorelkin, A. Kreuzberg V. Talskykh, E. Bykova, V. Aparin, I. Mirabdullaev, and R. Toryannikova............................................. 32 Water scarcity in the WESCANA Region: Threat or prospect for peace? Odeh Al-Jayyousi ......................................................................... 48 4 5 6 7 Summary The IUCN-WESCANA Water Publication – The Conservation and Sustainable Use Of Freshwater Resources in West Asia, Central Asia and North Africa - is the first publication of the IUCN-WESCANA Office, Amman-Jordan. -

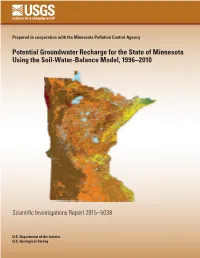

Potential Groundwater Recharge for the State of Minnesota Using the Soil-Water-Balance Model, 1996–2010

Prepared in cooperation with the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Potential Groundwater Recharge for the State of Minnesota Using the Soil-Water-Balance Model, 1996–2010 Scientific Investigations Report 2015–5038 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Map showing mean annual potential recharge rates from 1996−2010 based on results from the Soil-Water-Balance model for Minnesota. Potential Groundwater Recharge for the State of Minnesota Using the Soil-Water- Balance Model, 1996–2010 By Erik A. Smith and Stephen M. Westenbroek Prepared in cooperation with the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Scientific Investigations Report 2015–5038 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2015 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod/. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Smith, E.A., and Westenbroek, S.M., 2015, Potential groundwater recharge for the State of Minnesota using the Soil-Water-Balance model, 1996–2010: U.S.