The Art of NC Wyeth Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H. Con. Res. 215

III 103D CONGRESS 2D SESSION H. CON. RES. 215 IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES JUNE 21 (legislative day, JUNE 7), 1994 Received and referred to the Committee on Foreign Relations CONCURRENT RESOLUTION Honoring James Norman Hall and recognizing his outstand- ing contributions to the United States and the South Pacific. Whereas James Norman Hall, a native son of the State of Iowa born in Colfax in 1887, and a graduate of Grinnell College, was a decorated war hero, noted adventurer, and acclaimed author, who was revered and loved in France and Tahiti, and throughout the South Pacific; Whereas James Norman Hall exhibited an unwavering com- mitment to freedom and democracy by volunteering for military service early in World War I and by fighting alongside British forces in the worst of trench warfare, including the Battle of Loos, where he was one of few survivors; Whereas James Norman Hall continued his fight for liberty by becoming a pilot in the Lafayette Escadrille, an Amer- ican pursuit squadron of the French Air Service, and his courageous and daring feats in air battles earned him France's highest medals, including the Legion 1 2 d'Honneur, Medaille Militaire, and Croix de Guerre with 5 Palms; Whereas James Norman Hall was commissioned as a Captain in the United States Army Air Service when the United States entered World War I, continued his legendary ex- ploits as an ace pilot, acted as wing commander and mentor for then-Lieutenant Eddie Rickenbacker, and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross Medal, for gal- lantry and bravery -

Mutiny on the Bounty: a Piece of Colonial Historical Fiction Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega University of French Polynesia

4 Nordhoff and Hall’s Mutiny on the Bounty: A Piece of Colonial Historical Fiction Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega University of French Polynesia Introduction Various Bounty narratives emerged as early as 1790. Today, prominent among them are one 20th-century novel and three Hollywood movies. The novel,Mutiny on the Bounty (1932), was written by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall, two American writers who had ‘crossed the beach’1 and settled in Tahiti. Mutiny on the Bounty2 is the first volume of their Bounty Trilogy (1936) – which also includes Men against the Sea (1934), the narrative of Bligh’s open-boat voyage, and Pitcairn’s Island (1934), the tale of the mutineers’ final Pacific settlement. The novel was first serialised in the Saturday Evening Post before going on to sell 25 million copies3 and being translated into 35 languages. It was so successful that it inspired the scripts of three Hollywood hits; Nordhoff and Hall’s Mutiny strongly contributed to substantiating the enduring 1 Greg Dening, ‘Writing, Rewriting the Beach: An Essay’, in Alun Munslow & Robert A Rosenstone (eds), Experiments in Rethinking History, New York & London, Routledge, 2004, p 54. 2 Henceforth referred to in this chapter as Mutiny. 3 The number of copies sold during the Depression suggests something about the appeal of the story. My thanks to Nancy St Clair for allowing me to publish this personal observation. 125 THE BOUNTY FROM THE BEACH myth that Bligh was a tyrant and Christian a romantic soul – a myth that the movies either corroborated (1935), qualified -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

James Norman Hall

James Norman Hall James Norman Hall (* 22. April 1887 in Colfax, Iowa; † 5. Juli 1951 in Vaipoopoo, Tahiti) war ein US-amerikanischer Autor, der vor allem durch seinen Roman Mutiny on the Bounty (Meuterei auf der Bounty) bekannt ist. Leben Hall wurde in Colfax (Iowa) geboren, wo er die örtliche Schule besuchte. Nach Abschluss seiner Studien 1910 am Grinnell College war er zunächst in der Sozialarbeit in Boston (Massachusetts) tätig, gleichzeitig versuchte er sich als Schriftsteller zu etablieren und studierte für das Master's degree an der Harvard University. Im Sommer 1914 war Hall im Vereinigten Königreich in Urlaub, als der Erste Weltkrieg ausbrach. Er gab sich als Kanadier aus, meldete sich freiwillig für die British Army und diente bei den Royal Fusiliers als Maschinengewehrschütze während der Schlacht von Loos. Er wurde entlassen, nachdem seine wahre Nationalität festgestellt wurde, kehrte in die Vereinigten Staaten zurück und schrieb sein erstes Buch, Kitchener's Mob (1916), das von seinen Kriegserfahrungen in der Freiwilligenarmee von Lord Kitchener erzählte. Er kehrte nach Frankreich zurück und trat der Escadrille La Fayette bei, einem französisch-amerikanischen Fliegerkorps, bevor die Vereinigten Staaten offiziell in den Krieg eintraten. Hall wurde mit dem Croix de Guerre mit fünf Palmen und der Médaille Militaire ausgezeichnet. Als die Vereinigten Staaten in den Krieg eintraten, wurde Hall zum Captain im Army Air Service. Dort begegnete er einem anderen amerikanischen Piloten, Charles Nordhoff. Nachdem er abgeschossen wurde, verbrachte Hall die letzten Monate des Konfliktes als ein deutscher Kriegsgefangener. Er wurde in die französische Ehrenlegion aufgenommen und es wurde ihm das amerikanische Distinguished Service Cross verliehen. -

Fine Books in All Fields

Sale 480 Thursday, May 24, 2012 11:00 AM Fine Literature – Fine Books in All Fields Auction Preview Tuesday May 22, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, May 23, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, May 24, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. CONSIGN TO PBA GALLERIES PBA is always happy to discuss consignments of books, maps, photographs, graphics, autographs and related material. -

The South Pacific in the Works of Robert Dean Frisbie

UDK 821.111(73).09 Frisbie R. D. THE SOUTH PACIFIC IN THE WORKS OF ROBERT DEAN FRISBIE Natasa Potocnik Abstract Robert Dean Frisbie (1896-1948) was one of the American writers who came to live in the South Pacific and wrote about his life among the natives. He published six books between 1929 and his death in 1948. Frisbie was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on 16 April1896. He attended the Raja Yoga Academy at Point Loma in California. Later he enlisted in the U. S. army and was medically discharged from the army in 1918 with a monthly pension. After his work as a newspaper columnist and reporter for an army newspaper in Texas, and later for the Fresno Morning Republican, he left for Tahiti in 1920. In Tahiti he had ambitious writing plans but after four years of living in Tahiti, he left his plantation and sailed to the Cook Islands. He spent the rest of his life in the Cook Islands and married a local girl Ngatokorua. His new happiness gave him the inspiration to write. 29 sketches appeared in the United States in 1929, collected by The Century Company under the title of The Book of Puka-Puka. His second book My Tahiti, a book of memories, was published in 1937. After the death of Ropati 's beloved wife his goals were to bring up his children. But by this time Frisbie was seriously ill. The family left Puka-Puka and settled down on the uninhabited atoll of Suwarrow. Later on they lived on Rarotonga and Samoa where Frisbie was medically treated. -

" Mutiny on the Bounty": a Case Study for Leadership Courses

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 360 669 CS 508 256 AUTHOR Leeper, Roy V. TITLE "Mutiny on the Bounty": A Case Study for Leadership Courses. PUB DATE Apr 93 NOTE 13p.; Paper presented at the Joint Meeting of the Southern States Communication Association and the Central States Communication Association (Lexington, KY, April 14-18, 1993). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Behavioral Objectives; Case Studies; Class Activities; Classification; *Films; Higher Education; *Leadership; Thinking Skills IDENTIFIERS Gagnes Taxonomy; *Mutiny on the Bounty (Film) ABSTRACT Although there are drawbacks to the case study method, using films presents opportunities for instructors to teach to the "higher" levels presented in learning objective taxonomies. A number of classifications of learning outcomes or objectives are well served by a teaching style employing the case approach. There seem to be as many different types of case study methods as there are writers on the subject. Perhaps the most useful typology of case methods, in part because of its simplicity, is that de-eloped by Gay Wakefield for the public relations field. Because of the clarity of character and issue development, the 1935 film version of "Mutiny on the Bounty" was chosen for use in a sophomore level course titled "Principles of Leadership." Using Wakefield's typology, the film is a case history which becomes a case analysis during class discussion. Almost all lf the topics that would be covered in a course in leadership are present in the film. The film meets the requirements of a good case as set out by other typologies of case studies. -

James Norman Hall House

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-OO18 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory—Nomination Form ««»«.»,«,date entered jyL ( 2 [g84 See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_____________________________________ 1. Name ^BUM(-MI-^«~ — -— <• »••>•—--•--•-•- s,^ 1 historic James Normaii^Hally House 2. Location street & number 416 E. Howard not for publication city, town Colfax vicinity of state IA code 019 county Jasper code 099 3. Classification Category Ownership Status•y-y Present Use district public " occupied __ agriculture museum xx building(s) xx private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational xx private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process xx yes: restricted government scientific being considered _ yes: unrestricted industrial transportation N/A no military other: 4. Owner of Property name John W. and Nancy A. McKinstry street & number 81 High Street city, town Cclfax __ vicinity of state IA 50054 5. Location of Legal Description JasPer Ccunt y clerk ' s office courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Jasper County Courthouse street & number Newton IA city, town state 6. Representation in Existing Surveys tme CIRALG HISTORIC SITES SURVEY has this property been determined eligible? yes XX no date 1978 federal _ xx state county local depository for survey records i owa city, town Des Koines state IA 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered xx original site xx good ruins xx altered moved date fair unexposed /-. -

The Experience of War

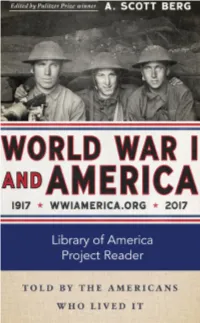

Introductions, headnotes, and back matter copyright © 2016 by Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y. Cover photograph: American soldiers in France, 1918. Courtesy of the National Archives. Woodrow Wilson: Copyright © 1983, 1989 by Princeton University Press. Vernon E. Kniptash: Copyright © 2009 by the University of Oklahoma Press. Mary Borden: Copyright © Patrick Aylmer 1929, 2008. Shirley Millard: Copyright © 1936 by Shirley Millard. Ernest Hemingway: Copyright © 1925, 1930 by Charles Scribner’s Sons, renewed 1953, 1958 by Ernest Hemingway. * * * The readings presented here are drawn from World War I and America: Told by the Americans Who Lived It. Published to mark the centenary of the Amer- ican entry into the conflict, World War I and America brings together 128 diverse texts—speeches, messages, letters, diaries, poems, songs, newspaper and magazine articles, excerpts from memoirs and journalistic narratives— written by scores of American participants and observers that illuminate and vivify events from the outbreak of war in 1914 through the Armistice, the Paris Peace Conference, and the League of Nations debate. The writers col- lected in the volume—soldiers, airmen, nurses, diplomats, statesmen, political activists, journalists—provide unique insight into how Americans perceived the war and how the conflict transformed American life. It is being published by The Library of America, a nonprofit institution dedicated to preserving America’s best and most significant writing in handsome, enduring volumes, featuring authoritative texts. You can learn more about World War I and America, and about The Library of America, at www.loa.org. For materials to support your use of this reader, and for multimedia content related to World War I, visit: www.WWIAmerica.org World War I and America is made possible by the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities. -

108 Stat. 5110 Concurrent Resolutions—Aug

108 STAT. 5110 CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS—AUG. 10, 1994 Aug. 10,1994 "THE CORNERSTONES OF THE UNITED STATES [s. Con. Res. 41] CAPITOL"—SENATE PRINT Resolved by the Senate (the House of Representatives concur ring). That there shall be printed as a Senate document, the book entitled 'The Cornerstones of the United States Capitol", prepared by the Office of the Architect of the Capitol. SEC. 2. Such document shall include illustrations, and shall be in such style, form, manner, and binding as directed by the Joint Committee on Printing sifter consultation with the Secretary of the Senate. SEC. 3. In addition to the usual number, there shall be printed, for the use of the Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Capitol, the lesser of— (1) 50,000 copies of the document; or (2) such number of copies of the document as does not exceed a total production and printing cost of $59,697. Agreed to August 10,1994. Aug. 23, 1994 [H. Con. Res. 215] HONORING JAMES NORMAN HALL Whereas James Norman Hall, a native son of the State of Iowa born in Colfax in 1887, and a graduate of Grinnell College, was a decorated war hero, noted adventurer, and acclaimed author, who was revered and loved in Frsince and Tahiti, and throughout the South Pacific; Whereas James Norman Hall exhibited an unwavering commitment to freedom and democracy by volunteering for military service early in World War I and by fighting alongside British forces in the worst of trench warfare, including the Battle of Loos, where he was one of few survivors; Whereas James Norman Hall -

Download the Project Reader

Introductions, headnotes, and back matter copyright © 2017 by Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y. Cover photograph: American soldiers in France, 1918. Courtesy of the National Archives. Woodrow Wilson: Copyright © 1983, 1989 by Princeton University Press. Vernon E. Kniptash: Copyright © 2009 by the University of Oklahoma Press. Mary Borden: Copyright © Patrick Aylmer 1929, 2008. Shirley Millard: Copyright © 1936 by Shirley Millard. Ernest Hemingway: Copyright © 1925, 1930 by Charles Scribner’s Sons, renewed 1953, 1958 by Ernest Hemingway. * * * The readings presented here are drawn from World War I and America: Told by the Americans Who Lived It. Published to mark the centenary of the American entry into the conflict, World War I and America brings together 128 diverse texts—speeches, messages, letters, diaries, poems, songs, newspaper and magazine articles, excerpts from memoirs and journalistic narratives—written by scores of American participants and observers that illuminate and vivify events from the outbreak of war in 1914 through the Armistice, the Paris Peace Conference, and the League of Nations debate. The writers collected in the volume—soldiers, airmen, nurses, diplomats, statesmen, political activists, journalists—provide unique insight into how Americans perceived the war and how the conflict transformed American life. It is being published by The Library of America, a nonprofit institution dedicated to preserving America’s best and most significant writing in handsome, enduring volumes, featuring authoritative texts. You can learn more about World War I and America, and about The Library of America, at www.loa.org. For materials to support your use of this reader, and for multimedia content related to World War I, visit: www.WWIAmerica.org World War I and America is made possible by the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities. -

85 Mutiny on the Bounty, By

93(2):102-103 Myers, Gloria E., A Municipal Mother: 95(4):212-13 Muth, Richard F., Regions, Resources, and Portland’s Lola Greene Baldwin, Myth and Memory: Stories of Indigenous- Economic Growth, review, 57(2):85 America’s First Policewoman, review, European Contact, ed. John Sutton Mutiny on the Bounty, by Charles Nordhoff 88(2):100-101 Lutz, review, 101(1):38 and James Norman Hall, review, Myers, Henry (politician), 64(1):18-20 The Mythic West in Twentieth-Century 25(1):65-67 Myers, Henry C. (professor), 20(3):174-75 America, by Robert G. Athearn, review, Mutschler, Charles V., “Great Spirits: Ruby Myers, John Myers, Print in a Wild Land, 79(1):37 and Brown, Pioneering Historians of review, 59(2):109; San Francisco’s Reign Mythology of Puget Sound, by Hermann the Indians of the Pacific Northwest,” of Terror, review, 58(4):217 Haeberlin, ed. Erna Gunther Spier, 95(3):126-29; ed., A Doctor among Myers, Polly Reed, “Boeing Aircraft 18(2):149 the Oglala Sioux Tribe: The Letters of Company’s Manpower Campaign Myths and Legends of Alaska, by Katharine Robert H. Ruby, 1953-1954, by Robert during World War II,” 98(4):183-95; Berry Judson, review, 3(2):158 H. Ruby, review, 102(2):91-92; rev. of Capitalist Family Values: Gender, Myths and Legends of British North America, Get Mears! Frederick Mears, Builder Work, and Corporate Culture at by Katharine B. Judson, 8(3):233-34 of the Alaska Railroad, 95(3):157- Boeing, review, 106(3):154; rev. of Take Myths and Legends of the Great Plains, ed.