California State University, Northridge Conducting the Elgar Enigma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Andrew Davis the Grainger Collection / Topfoto / Arenapal

elgar FALSTAFF orchestral songs ‘grania and diarmid’ incidental music and funeral march roderick williams baritone sir andrew davis Sir Edward c. 1910 Elgar, The Grainger Collection / TopFoto / ArenaPAL Sir Edward Elgar (1857 – 1934) Falstaff, Op. 68 (1913) 35:57 Symphonic Study in C minor • in c-Moll • en ut mineur for Full Orchestra Dedicated to Sir Landon Ronald 1 I Falstaff and Prince Henry. Allegro – Con anima – Animato – Allegro molto – Più animato – 3:09 2 II Eastcheap. Allegro molto – Molto grandioso e largamente – Tempo I – Poco più tranquillo – 2:54 3 Gadshill. A Tempo I – The Boar’s Head. Revelry and sleep. Allegro molto – Con anima – Più lento – Giusto, con fuoco – Poco tranquillo – Allegro molto – Poco più lento – Allegro – Poco a poco più lento – 9:21 4 Molto tranquillo – Molto più lento – 1:14 5 Dream Interlude. Poco allegretto – 2:36 6 III Falstaff’s march. Allegro – Con anima – Poco meno mosso – Animato – A tempo [Poco meno mosso] – 2:58 7 The return through Gloucestershire. [ ] – Poco sostenuto – Poco a poco più lento – 1:27 8 Interlude. Gloucestershire, Shallow’s orchard. Allegretto – 1:34 3 9 The new king. Allegro molto – The hurried ride to London. [ ] – 1:06 10 IV King Henry V’s Progress. Più moderato – Giusto – Poco più allegro – Animato – Grandioso – Animato – 3:29 11 The repudiation of Falstaff, and his death. [ ] – Poco più lento – Poco più lento – Più lento – Poco animato – Poco più mosso – A tempo giusto al fine 6:00 Songs, Op. 59 (1909 – 10)* 6:31 12 3 Oh, soft was the song. Allegro molto 1:52 13 5 Was it some golden star? Allegretto – Meno mosso – Più mosso – Meno mosso – Tempo I 2:10 14 6 Twilight. -

The Hills of Dreamland

SIR EDWARD ELGAR (1857-1934) The Hills of Dreamland SOMMCD 271-2 The Hills of Dreamland Orchestral Songs The Society Complete incidental music to Grania and Diarmid Kathryn Rudge mezzo-soprano† • Henk Neven baritone* ELGAR BBC Concert Orchestra, Barry Wordsworth conductor ORCHESTRAL SONGS CD 1 Orchestral Songs 8 Pleading, Op.48 (1908)† 4:02 Song Cycle, Op.59 (1909) Complete incidental music to 9 Follow the Colours: Marching Song for Soldiers 6:38 1 Oh, soft was the song (No.3) 2:00 *♮ * (1908; rev. for orch. 1914) GRANIA AND DIARMID 2 Was it some golden star? (No.5) 2:44 * bl 3 Twilight (No.6)* 2:50 The King’s Way (1909)† 4:28 4 The Wind at Dawn (1888; orch.1912)† 3:43 Incidental Music to Grania and Diarmid (1901) 5 The Pipes of Pan (1900; orch.1901)* 3:46 bm Incidental Music 3:38 Two Songs, Op. 60 (1909/10; orch. 1912) bn Funeral March 7:13 6 The Torch (No.1)† 3:16 bo Song: There are seven that pull the thread† 3:33 7 The River (No.2)† 5:24 Total duration: 53:30 CD 2 Elgar Society Bonus CD Nathalie de Montmollin soprano, Barry Collett piano Kathryn Rudge • Henk Neven 1 Like to the Damask Rose 3:47 5 Muleteer’s Serenade♮ 2:18 9 The River 4:22 2 The Shepherd’s Song 3:08 6 As I laye a-thynkynge 6:57 bl In the Dawn 3:11 3 Dry those fair, those crystal eyes 2:04 7 Queen Mary’s Song 3:31 bm Speak, music 2:52 BBC Concert Orchestra 4 8 The Mill Wheel: Winter♮ 2:27 The Torch 2:18 Total duration: 37:00 Barry Wordsworth ♮First recordings CD 1: Recorded at Watford Colosseum on March 21-23, 2017 Producer: Neil Varley Engineer: Marvin Ware TURNER CD 2: Recorded at Turner Sims, Southampton on November 27, 2016 plus Elgar Society Bonus CD 11 SONGS WITH PIANO SIMS Southampton Producer: Siva Oke Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor Booklet Editor: Michael Quinn Front cover: A View of Langdale Pikes, F. -

Paul Lewis in Recital a Feast of Piano Masterpieces

PAUL LEWIS IN RECITAL A FEAST OF PIANO MASTERPIECES SAT 14 SEP 2019 QUEENSLAND SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA STUDIO PROGRAM | PAUL LEWIS IN RECITAL I WELCOME Welcome to this evening’s recital. I have been honoured to join Queensland Symphony Orchestra this year as their Artist-in- Residence, and am delighted to perform for you tonight. This intimate studio is a perfect setting for a recital, and I very much hope you will enjoy it. The first work on the program is Haydn’s Piano Sonata in E minor. Haydn is well known for his string quartets but he also wrote a great number of piano sonatas, and this one is a particular gem. It showcases the composer’s skill of creating interesting variations of simple musical material. The Three Intermezzi Op.117 are some of Brahms’s saddest and most heartfelt piano pieces. The first Intermezzo was influenced by a Scottish lullaby,Lady Anne Bothwell’s Lament, and was described by Brahms as a ‘lullaby to my sorrows’. This is Brahms in his most introspective mood, with quietly anguished harmonies and dynamic markings that rarely rise above mezzo piano. Finally, tonight’s recital concludes with one of the great peaks of the piano repertoire. The 33 Variations in C on a Waltz by Diabelli is one of Beethoven’s most extreme and all- encompassing works – an unforgettable journey for the listener as much as the performer. Thank you for your attendance this evening and I hope you enjoy the performance. Paul Lewis 2019 Artist-in-Residence IN THIS CONCERT PROGRAM Piano Paul Lewis Haydn Piano Sonata in E minor, Hob XVI:34 Brahms Three Intermezzi, Op.117 INTERVAL Approx. -

Two Letters by Anton Bruckner

Two Letters by Anton Bruckner Jürgen Thym Bruckner ALS, 13.XI.1883 Lieber Freund! Auf Gerathewohl schreibe ich; denn Ihr Brief ist versteckt. Weiß weder Ihre Adresse noch sonstigen Charakter von Ihnen. Danke sehr für Ihr liebes Schreiben. Omnes amici mei dereliquerunt me! In diesen Worten haben Sie die ganze Situation. Hans Richter nennt mich jetzt musik [alischen] Narren weil ich zu wenig kürzen wollte; (wie er sagt;) führt natürlich gar nichts auf; ich stehe gegenwärtig ganz allein da. Wünsche, daß es Ihnen besser ergehen möge, und Sie bald oben hinauf kommen mögen! Dann werden Sie gewiß meiner nicht vergessen. Glück auf! Ihr A. Bruckner Wien, 13. Nov. 1883 Dear Friend: I take the risk or writing to you, even though I cannot find your letter and know neither your address nor title. Thank you very much for your nice letter. All my friends have abandoned me! These words tell you the whole situation. Hans Richter calls me now a musical fool, because I did not want to make enough cuts (as he puts it). And, of course, he does not perform anything at all; I stand alone at the moment. I hope that things will be better for you and that you will soon succeed then you will surely not forget me. Good luck! Your A. Bruckner Vienna, November 13, 1883 Bruckner, ALS, 27.II.1885 Hochgeborener Herr Baron! Schon wieder muß ich zur Last fallen. Da die Sinfonie am 10. März aufgeführt wird, so komme ich schon Sonntag den 8. März früh nach München und werde wieder bei den vier Jahreszeiten Quartier nehmen. -

52183 FRMS Cover 142 17/08/2012 09:25 Page 1

4884 cover_52183 FRMS cover 142 17/08/2012 09:25 Page 1 Autumn 2012 No. 157 £1.75 Bulletin 4884 cover_52183 FRMS cover 142 17/08/2012 09:21 Page 2 NEW RELEASES THE ROMANTIC VIOLIN STEPHEN HOUGH’S CONCERTO – 13 French Album Robert Schumann A master pianist demonstrates his Hyperion’s Romantic Violin Concerto series manifold talents in this delicious continues its examination of the hidden gems selection of French music. Works by of the nineteenth century. Schumann’s late works Poulenc, Fauré, Debussy and Ravel rub for violin and orchestra had a difficult genesis shoulders with lesser-known gems by but are shown as entirely worthy of repertoire their contemporaries. status in these magnificent performances by STEPHEN HOUGH piano Anthony Marwood. ANTHONY MARWOOD violin CDA67890 BBC SCOTTISH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA CDA67847 DOUGLAS BOYD conductor MUSIC & POETRY FROM THIRTEENTH-CENTURY FRANCE Conductus – 1 LOUIS SPOHR & GEORGE ONSLOW Expressive and beautiful thirteenth-century vocal music which represents the first Piano Sonatas experiments towards polyphony, performed according to the latest research by acknowledged This recording contains all the major works for masters of the repertoire. the piano by two composers who were born within JOHN POTTER tenor months of each other and celebrated in their day CHRISTOPHER O’GORMAN tenor but heard very little now. The music is brought to ROGERS COVEY-CRUMP tenor modern ears by Howard Shelley, whose playing is the paradigm of the Classical-Romantic style. HOWARD SHELLEY piano CDA67947 CDA67949 JOHANNES BRAHMS The Complete Songs – 4 OTTORINO RESPIGHI Graham Johnson is both mastermind and Violin Sonatas pianist in this series of Brahms’s complete A popular orchestral composer is seen in a more songs. -

Programme Scores 180627Da

Symposium Richard Wagner and his successors in the Austro-German conducting tradition Friday/Saturday, 2/3 November 2018 Bern University of the Arts, Papiermühlestr. 13a/d A symposium of the Research Area Interpretation – Bern University of the Arts, in collaboration with the Royal Academy of Music, London www.hkb-interpretation.ch/annotated-scores Richard Wagner published the first major treatise on conducting and interpretation in 1869. His ideas on how to interpret the core Classical and early Romantic orchestral repertoire were declared the benchmark by subsequent generations of conductors, making him the originator of a conducting tradition by which those who came after him defined their art – starting with Wagner’s student Hans von Bülow and progressing from him to Arthur Nikisch, Felix Weingartner, Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Wilhelm Furtwängler and beyond. This conference will bring together leading experts in the research field in question. A workshop and concert with an orchestra with students of the Bern University of the Arts, the Hochschule Luzern – Music and the Royal Academy of Music London, directed by Prof. Ray Holden from the project partner, the Royal Academy of Music, will offer a practical perspective on the interpretation history of the Classical repertoire. A symposium of the Research Area Interpretation – Bern University of the Arts, in collaboration with the Royal Academy of Music, London Head Research Area Interpretation: Martin Skamletz Responsible for the conference: Chris Walton Scientific collaborator: Daniel Allenbach Administration: Sabine Jud www.hkb.bfh.ch/interpretation www.hkb-interpretation.ch Funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation SNSF Media partner Symposium Richard Wagner and his successors Friday, 2 November 2018 HKB, Kammermusiksaal, Papiermühlestr. -

Download American Friends Leaflet

≥ HANDS ACROSS THE WATER AMERICAN FRIENDS www.halle.co.uk @the_halle | thehalle | TheHalleOfficial | @the_halle Sir Charles Hallé The Hallé is the only major orchestra in the world named after its founder An Introduction to the Hallé There are three Hallé American Friend levels to choose from and in APPLICATION FORM recognition of your gift, the Hallé offers the following: The Hallé Orchestra (which is a registered charity) was founded in Name: Manchester in the North of England in 1858 in the middle of the industrial Barbirolli, from $1,500 per annum ($1,450 tax deductable) Address: revolution. As one of Europe’s oldest orchestras the Hallé was founded Exclusive access to Archive Newsletter and website pages • City & State: on the basis that the highest quality music should be accessible to all and • Opportunity to explore Hallé archive with personal support from the Archive this remains one of the organizations key principles to this day. Sir Mark Department for research and/or visits to the Archive in Manchester Zip Code: Elder became Music Director of the Halle in 2000 and has deepened and • Season Brochures (annually) and Member’s Newsletter mailing (3 annually) Telephone: extended the orchestra’s reputation as a world class ensemble with an • Acknowledgement of support in Hallé print including concert programmes and on enviable recording profile. The orchestra performs across the UK and the website Email: world and is resident at the internationally renowned Bridgewater Hall in • First press of each new Hallé CD release Company or Foundation (if applicable): • Advanced notice for any performance featuring Sir Mark taking place in US. -

Edward Elgar: Enigma Variations What Secret? Perusal Script Not for Performance Use Copyright © 2010 Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Edward Elgar: Enigma Variations What Secret? Perusal script Not for performance use Copyright © 2010 Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Duplication and distribution prohibited. In addition to the orchestra and conductor: Five performers Edward Elgar, an Englishman from Worcestershire, 41 years old Actor 2 (female) playing: Caroline Alice Elgar, the composer's wife Carice Elgar, the composer's daughter Dora Penny, a young woman in her early twenties Snobbish older woman Actor 3 (male) playing: William Langland, the mediaeval poet Arthur Troyte Griffith (Ninepin), an architect in Malvern Richard Baxter Townsend, a retired adventurer William Meath Baker, a wealthy landowner George Robertson Sinclair, a cathedral organist August Jaeger (Nimrod), a German music-editor William Baker, son of William Meath Baker Old-fashioned musical journalist Pianist Narrator Page 1 of 21 ME 1 Orchestra, theme, from opening to figure 1 48" VO 1 Embedded Audio 1: distant birdsong NARRATOR The Malvern Hills... A nine-mile ridge of rock in the far west of England standing about a thousand feet above the surrounding countryside... From up here on a clear day you can see far into the distance... on one side... across the patchwork fields of Herefordshire to Wales and the Black Mountains... on another... over the river Severn... Shakespeare's beloved river Avon... and the Vale of Evesham... to the Cotswolds... Page 2 of 21 and... if you're lucky... to the north, you can just make out the ancient city of Worcesteri... and the tall square tower of its cathedral... in the shadow of which... Edward Elgar spent his childhood and his youth.. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Mellon Grand Classics Season

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Mellon Grand Classics Season April 23, 2017 MANFRED MARIA HONECK, CONDUCTOR TILL FELLNER, PIANO FRANZ SCHUBERT Selections from the Incidental Music to Rosamunde, D. 644 I. Overture II. Ballet Music No. 2 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Concerto No. 3 for Piano and Orchestra in C minor, Opus 37 I. Allegro con brio II. Largo III. Rondo: Allegro Mr. Fellner Intermission WOLFGANG AMADEUS Symphony No. 41 in C major, K. 551, “Jupiter” MOZART I. Allegro vivace II. Andante cantabile III. Allegretto IV. Molto allegro PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA FRANZ SCHUBERT Overture and Ballet Music No. 2 from the Incidental Music to Rosamunde, D. 644 (1820 and 1823) Franz Schubert was born in Vienna on January 31, 1797, and died there on November 19, 1828. He composed the music for Rosamunde during the years 1820 and 1823. The ballet was premiered in Vienna on December 20, 1823 at the Theater-an-der-Wein, with the composer conducting. The Incidental Music to Rosamunde was first performed by the Pittsburgh Symphony on November 9, 1906, conducted by Emil Paur at Carnegie Music Hall. Most recently, Lorin Maazel conducted the Overture to Rosamunde on March 14, 1986. The score calls for pairs of woodwinds, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani and strings. Performance tine: approximately 17 minutes Schubert wrote more for the stage than is commonly realized. His output contains over a dozen works for the theater, including eight complete operas and operettas. Every one flopped. Still, he doggedly followed each new theatrical opportunity that came his way. -

Nikolaj Znaider in 2016/17

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Sunday 29 May 2016 7pm Barbican Hall BEETHOVEN VIOLIN CONCERTO Beethoven Violin Concerto London’s Symphony Orchestra INTERVAL Elgar Symphony No 2 Sir Antonio Pappano conductor Nikolaj Znaider violin Concert finishes approx 9.20pm 2 Welcome 29 May 2016 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief A very warm welcome to this evening’s LSO ELGAR UP CLOSE ON BBC iPLAYER concert at the Barbican. Tonight’s performance is the last in a number of programmes this season, During April and May, a series of four BBC Radio 3 both at the Barbican and LSO St Luke’s, which have Lunchtime Concerts at LSO St Luke’s was dedicated explored the music of Elgar, not only one of to Elgar’s moving chamber music for strings, with Britain’s greatest composers, but also a former performances by violinist Jennifer Pike, the LSO Principal Conductor of the Orchestra. String Ensemble directed by Roman Simovic, and the Elias String Quartet. All four concerts are now We are delighted to be joined once more by available to listen back to on BBC iPlayer Radio. Sir Antonio Pappano and Nikolaj Znaider, who toured with the LSO earlier this week to Eastern Europe. bbc.co.uk/radio3 Following his appearance as conductor back in lso.co.uk/lunchtimeconcerts November, it is a great pleasure to be joined by Nikolaj Znaider as soloist, playing the Beethoven Violin Concerto. We also greatly look forward to 2016/17 SEASON ON SALE NOW Sir Antonio Pappano’s reading of Elgar’s Second Symphony, following his memorable performance Next season Gianandrea Noseda gives his first concerts of Symphony No 1 with the LSO in 2012. -

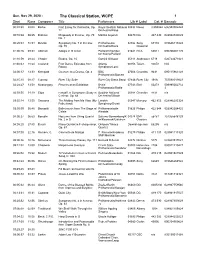

29, 2020 - the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Nov 29, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 08:08 Barber First Essay for Orchestra, Op. Royal Scottish National 08830 Naxos 8.559024 636943902424 12 Orchestra/Alsop 00:10:3808:25 Brahms Rhapsody in B minor, Op. 79 Martha Argerich 04470 DG 447 430 028944743029 No. 1 00:20:03 38:53 Dvorak Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Philharmonia 02982 Sony 67174 074646717424 Op. 70 Orchestra/Davis Classical 01:00:2609:33 Albinoni Adagio in G minor Paillard Chamber 01641 RCA 60011 090266001125 Orchestra/Paillard 01:10:59 28:44 Chopin Etudes, Op. 10 Garrick Ohlsson 05311 Arabesque 6718 026724671821 01:40:4318:24 Copland Four Dance Episodes from Atlanta 00356 Telarc 80078 N/A Rodeo Symphony/Lane 02:00:3713:33 Korngold Overture to a Drama, Op. 4 BBC 07006 Chandos 9631 095115963128 Philharmonic/Bamert 02:15:1008:17 Curnow River City Suite River City Brass Band 07846 River City 198A 753598019823 02:24:2733:58 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition Berlin 07743 EMI 00273 509995002732 Philharmonic/Rattle 3 02:59:55 34:19 Elgar Falstaff, A Symphonic Study in Scottish National 00988 Chandos 8431 n/a C minor, Op. 68 Orchestra/Gibson 03:35:1413:55 Smetana The Moldau from Ma Vlast (My London 05047 Mercury 462 953 028946295328 Fatherland) Symphony/Dorati 03:50:09 08:48 Donizetti Ballet music from The Siege of Philharmonia/de 01826 Philips 422 844 028942284425 Calais Almeida 04:00:2706:53 Borodin Nocturne from String Quartet Salerno-Sonnenberg/K 04974 EMI 56481 724355648129 No.