A New Look at the Golden Spike Ceremony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herefordshire Green Infrastructure Strategy

Green Infrastructure Strategy Herefordshire Local Development Framework February 2010 This page is deliberately left blank CONTENTS Preface PART 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background 1 1.2 What is Green Infrastructure? 3 1.3 Aims & Objectives of the Strategy 3 1.4 Report Structure 5 2.0 GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE IN CONTEXT 2.1 Origins & Demand for the Strategy 7 2.2 Policy Background & Relationship to Other Plans 7 2.2.1 National Policy 8 2.2.6 Regional Policy 10 2.2.7 Local Policy 10 2.2.8 Biodiversity Action Plan 11 2.2.9 Sustainable Community Strategy 11 2.3 Methodology 11 2.3.1 Identification of Assets 11 2.3.5 Assessment of Deficiencies & Needs 12 2.3.7 Strategic Geographic Tiers – Definition & Distribution 13 2.3.11 Sensitivity & Opportunity 16 2.3.13 Guiding Policies 16 2.3.14 Realising Green Infrastructure – the Delivery Mechanism 17 3.0 GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE ASSETS – ISSUES & OPPORTUNITIES 3.1 General 19 3.2 Strategic Geographic Tiers 21 3.3 Natural Systems - Geology 23 - Hydrology 29 - Topography 35 -Biodiversity 41 3.4 Human Influences - Land Use 49 -Access & Movement 55 - Archaeology, Historical & Cultural 63 - Landscape Character 71 - Designated & Accessible Open Space 81 3.5 Natural Resources Summary 91 3.6 Human Influences Summary 91 PART 2 4.0 THE GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE FRAMEWORK 4.1 General 93 4.2 A Vision for Green Infrastructure in Herefordshire 94 4.3 The Green Infrastructure Framework 95 4.3.1 Deficiencies & Needs 95 4.3.6 Strategic Tiers 98 4.3.7 County Vision 100 4.3.8 County Strategic Corridors 100 4.3.9 County Strategic Areas -

A Dccconcepts “Modelling Advice” Publication

A DCCconcepts “Modelling advice” publication DCC Advice #11 Page 1 Wiring Point-work & Special track conditions for DC or DCC Wiring the track… In plain English, with diagrams! If we had a $ or £ or € for every time we’ve been asked how to wire track and point-work, we’d be writing this on a beach somewhere while sipping a cold beer! A great layout needs good trackwork, so first - a word about trackwork and getting good performance. Choose carefully! DO think about making your own turnouts if you have even moderate skills. It is not as hard as you think, needs only basic skills and tools... and we do our best to make it easy with our top quality gauges, trackwork frets and templates. PLUS we will soon provide a detailed “How to make track” tutorial too. Interested? Then call or email us and we will do our best to help you. No matter what scale you will model in, DO NOT even consider using insulated frogs! Yes, lazy retailers who do not understand what they sell - and modellers who have never done a proper job of laying track so it runs well may well recommend it to you… but do NOT be tempted. No matter which brand makes the turnouts, if you use insulated frogs, you WILL have small locos stalling or also suffer from wider wheels bridging the frog tip and creating momentary shorts that are hard to fix and really are a source of constant frustration. Use more realistic rail sizes please: Usually this will be code 55 in N, or Code 75 and 83 in OO or HO Scale. -

Missoula County the WYE Targeted Economic Development District (TEDD) Comprehensive Development Plan

Missoula County The WYE Targeted Economic Development District (TEDD) Comprehensive Development Plan (Mapcarta, n.d.) Figure 1. Wye Area Adopted by the Missoula Board of County Commissioners 2020 Figure 2. Summit Drive Acknowledgements Missoula County Board of Commissioners, Josh Slotnick, Chair Missoula Development Authority, Dori Brownlow Community and Planning Services, Karen Hughes, Lindsey Romaniello, and Andrew Stickney Project Consultants – Community Development Services of Montana, Janet Cornish and Lanette Windemaker The WYE TEDD – Comprehensive Development Plan – 2020 Table of Contents Chapter Page 1. Introduction and Overview ........................................................................................ 1 2. Portrait of the WYE TEDD ........................................................................................... 6 3. Infrastructure Analysis - Statement of Infrastructure Deficiencies and Area Eligibility 13 4. Planning Consistency & Zoning Accordance with the Missoula County Growth Policy 17 5. Goals of the WYE TEDD ............................................................................................ 27 6. Targeted Economic Development Activities .............................................................. 31 7. Program Administration ........................................................................................... 38 8. Plan Amendments .................................................................................................... 41 References .................................................................................................................. -

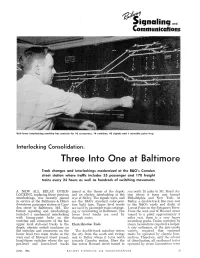

Interlocking Consolidation: Three Into One at Baltimore

~~ Siqnalinq and Communications Unit lever interlocking machine has controls for 10 crossovers, 14 switches, 45 signals and 1 movable point frog Interlocking Consolidation: Three Into One at Baltimore Track changes and interlockings modernized at the B&O's Camden ·street station where traffic includes 55 passenger and 170 freight trains every 24 hours as well as hundreds of switching movements A NEvV ALL RELAY INTER joined at the throat of the depot; run north H~ miles to Nit. Royal sta LOCKING, replacing three previous and an electric interlocking at the tion where it turns east toward interlockings, was recently placed wye at Bailey. The signals were, and Philadelphia and New York. At in service at the Baltimore & Ohio's are the B&O's standard color-posi Bailey, a double-track line runs east downtown passenger station at Cam tion light type. Upper level tracks to the B&O's yards and docks at den street in Baltimore, 11d. The are used by passenger trains originat Locust Point on the Patapasco River. former signaling and interlockings ing or terminating at Baltimore. The From the west end of Howard street included a mechanical· interlocking lower level tracks are used by tunnel to a point approximately 3 with facing-point locks on the through trains. miles east, there is a very heavy switches and crossovers of the five ascending grade. Trains operated by upper level stub-end tracks in the Electrification Ends steam locomotives required a helper. depot; electric switch machines on A city ordinance, of the anti-smoke the switches and crossovers on the The double-track mainline enters variety, required that eastward lower level two main tracks at the the city from the south and swings trains be operated by electric loco west end of Howard street tunnel; east to Bailey where it turns north motives. -

Scalefour Southwest Guide 2012 V2 Package

Scalefour SouthWest Guide 2012 SCALEFOUR SOUTHWEST 2012 a part of RAILWELLS The Town Hall, Market Place, Wells, Somerset BA5 2RB Saturday 11 August - 10.30 to 17.30 Sunday 12 August - 10.30 to 17.00 Adult - £5.00 Seniors - £4.00 Unaccompanied Children - £4.00 Accompanied children under 15 - free Website: www.railwells.com Photo: Wells Tourist Office Touris............................. Society members can use their Saturday tickets on Sunday also, but must show their membership card and have their ticket endorsed on Saturday. As we say every year, because we believe it: Railwells has become a very special show in the railway modelling calendar. Once again it is being held in the delightful setting of Wells Town Hall. Railwells includes Scalefour Southwest as an integral part of this annual event. Scalefour Southwest is an annual part of the exhibition, and this year is joined by a special section for EM Gauge, complemented by demonstrators showing how to convert to and model in EM. The exhibition has two layouts under construction to show you how, Black Lion Crossing by Geoff Kent and Bristol Barrow Road by Robin Whittle. There will be at least 50 exhibits this year including 14 layouts, 17 traders, as well as how-to demonstrations and other displays with emphasis on layout and stock construction. Whether you are considering constructing a layout or not it is always interesting to see what someone else has done. All this will make the show well worth a visit. Refreshments Available all day, starting with breakfast baguettes and going on to ploughman's lunches and afternoon tea and cake. -

Yhich Occurred on the Great Northern Railway at St

1392 INTERSTATE COMMERCE COMMISSION REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR OF THE BUREAU OF SAFETY IN RE INVESTIGATION OF AN ACCIDENT 'YHICH OCCURRED ON THE GREAT NORTHERN RAILWAY AT ST. PAUL, MINN , ON JAN UARY 9, 1928. March 20, 1928 To the Commission- On January 9, 1928, there was a side collision between a Chicago, St Paul, Minneapolis & Omaha Railway express tram and a Chicago Great Western F.ailroad passenger tram on the tracks of the Great Northern Railway at St. Paul, Mmn , resulting in the death of one employee and the in jury of three employees. Location and method of operation This accident occurred on the First Subdivision of the St Cloud Division, extending between Sc Paul and Clear water Junction, Mmn , a distance of 13.] 8 miles, m the im mediate vicinity of tne point of accident the Great Northern Railway is a four-track line over which trams are operated by time-table, tram orders and an automatic block-signal system Tne tracks ore designated from north to couth, as the westbound passenger track, the eastbound passenger track, the westbound freight -crack and the eastbound freight track The accident occurred Vwithm yard limits at a cross over located about 1-jL miles west of St. Paul Union Station or approximately 587 feet east of "Westminster interlocking tower; this crossover connects the westbound passenger track with the eastbound passenger track At a point 53.6 feet west of the west switch of the crossover, this sv/itch being located on the westbound track, there is a wye switch, facing-point for westbound movements, which connects the westbound track with the east leg of a wye, this wye track curving for westbound movements to the right, toward East St. -

The Ten Commandments of Model Railroad Yard Design

The Ten Commandments of Model Railroad Yard Design By Craig Bisgeier Sample Yard Layout You may find it helpful to print out this diagram before reading the article. Having a hard copy of the diagram to refer to as you are reading will probably be a big help for some of the more difficult concepts. This is definitely a case of a picture being worth a thousand words... One of the most often modeled -- and misunderstood -- layout design elements is the yard. Nearly everyone has one on their layout, whether it's used simply for car storage or as an actual operating tool. Unfortunately, many of them don't work very well. Common design mistakes are made over and over again by beginner and intermediate modelers. They can't be faulted, though, because the info on how to design a good yard is very hard to find. Even when the hobby press gets it right, it's short-lived, because if you missed the issue you didn't see it. Most of the time you see poor examples (like the hated Timesaver) which are often published by the hobby press without comment, and therefore accepted by those who do not know better as good design. So the "secrets" of good yard design are difficult to for most to uncover, because the good nuggets of information appear in wildly different places like out of print magazines or books, special interest publications, or even word of mouth among advanced modelers. not many modelers have that kind of library or access. What is needed is a repository where all the good ideas can be collected, stored, edited and presented as one all-encompassing primer on the subject. -

Corpus Christi and Yoakum Districts

Corpus Christi – Yoakum Regional Freight Mobility Study, Phase II Report TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ES-1 SECTION 7 - ANALYSIS OF RAIL/ROADWAY INTERFACE ISSUES .....................................7-1 7.1 METHODOLOGY.......................................................................................................7-1 7.1.1 Crossing Selection Criteria.............................................................................7-1 7.1.2 Rail Occupancy ..............................................................................................7-4 7.1.3 Analysis of Results .........................................................................................7-8 7.2 GRADE CROSSING COST/BENEFIT ANALYSIS...................................................7-10 7.2.1 Construction Cost Estimates ........................................................................7-10 7.2.2 Benefit-Cost Analysis ...................................................................................7-26 7.3 RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................7-31 SECTION 8 - BOTTLENECK IMPROVEMENTS EVALUATION AND MODELING ..................8-1 8.1 PROJECTED TRAFFIC GROWTH ............................................................................8-1 8.1.1 2035 Train Forecasts......................................................................................8-1 8.1.2 Results............................................................................................................8-2 -

South Dakota's Railroads

South Dakota’s Railroads South Dakota State Historic Preservation Office South Dakota’s Railroads: An Historic Context Prepared for: South Dakota State Historic Preservation Office 900 Governors Drive Pierre, South Dakota 57501 Prepared by: Mark Hufstetler and Michael Bedeau Renewable Technologies, Inc. 511 Metals Bank Bldg. Butte, Montana 59701 July 1998 Revised, December 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.................................................................................................................................2 A. Purpose of this Document..............................................................................................2 B. Methodology ..................................................................................................................3 2. The Importance of Railroads to South Dakota ...........................................................................4 3. The History of Railroading in South Dakota..............................................................................5 A. Geographical Background .............................................................................................5 B. Establishment and Expansion: South Dakota Railroads in the Nineteenth Century......6 1. Beginnings (1851-1868) .....................................................................................6 2. The Little Dakota Boom and the First Railroads (1868-1873)...........................8 3. Railway Expansion During the Great Dakota Boom (1878-1887).....................9 4. The Impact and -

RAIL RELOCATION PROJECTS in the U.S.: CASE STUDIES : and LESSONS for TEXAS RAIL PLANNING November 2006 Published: March 2007 6

Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA/TX-07/0-5322-1 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date : RAIL RELOCATION PROJECTS IN THE U.S.: CASE STUDIES : AND LESSONS FOR TEXAS RAIL PLANNING November 2006 Published: March 2007 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Curtis A. Morgan, Jeffery E. Warner, Craig E. Roco, Glenn C. Report 0-5322-1 Anderson, Leslie E. Olson, and Stephen S. Roop 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Texas Transportation Institute The Texas A&M University System 11. Contract or Grant No. College Station, Texas 77843-3135 Project 0-5322 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Texas Department of Transportation Technical Report: Research and Technology Implementation Office September 2005 – August 2006 P. O. Box 5080 Austin Texas 78763-5080 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes Project performed in cooperation with the Texas Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration. Project Title: Investigation of Rail Facilities Relocation in the U.S. and Potential Lessons for Texas Rail Planning Initiatives URL: http://tti.tamu.edu/documents/0-5322-1.pdf 16. Abstract Freight transportation is a major component of the transportation activity in metropolitan areas of Texas where both highway and rail routes converge. Traffic conflicts in urban areas are especially acute in areas surrounding urban rail facilities. Rail operations are also greatly hindered in urban rail facilities, which are often surrounded by incompatible land-use activities. -

Alabama Rail Directory

Photo by WILLIAM MARTIN Alabama Rail Directory Bureau of Transportation Planning and Modal Programs June 2014 2013 Alabama Rail Directory Prepared for Alabama Department of Transportation Bureau of Transportation Planning and Modal Programs Prepared by J. R. Wilburn and Associates, Inc. June 2014 2013 Alabama Rail Directory Alabama Department of Transportation TABLE OF CONTENTS THE RAILROADS IN ALABAMA Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 Map of the Railroads in Alabama .................................................................................. 2 CLASS I RAILROADS IN ALABAMA Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway Co. (BNSF) .......................................................... 4 Canadian National Illinois Central (CN/IC) ................................................................... 11 CSX Transportation, Inc. (CSXT) ................................................................................ 14 Norfolk Southern Corporation (NS) ............................................................................. 18 CLASS II (REGIONAL) RAILROADS IN ALABAMA Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway, LLC (AGR)^................................................................. 25 CLASS III (SHORTLINE/LOCAL) RAILROADS IN ALABAMA Alabama & Tennessee River Railway, LLC (ATN) ........................................................... 29 Alabama Railroad Co. (ALAB) ..................................................................................... 31 Alabama -

Evaluation of Alternative Detection Technologies for Trains and Highway Vehicles at Highway Rail Intersections 6

U.S. Department Evaluation of Alternative Detection of Transportation Federal Railroad Technologies for Trains and Highway Administration Vehicles at Highway Rail Intersections Office of Research and Development Washington, DC 20590 Safety of Highway-Railroad Grade Crossings DOT/FRA/ORD-03/04 February 2003 This document is available to the Final Report public through the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA 22161 and FRA web site at www.fra.dot.gov RAIL ROAD always e pect a train CROSSING Disclaimer: This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers' names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the object of this report. 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. DOT/FRA/ORD-03/04 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date February 2003 Evaluation of Alternative Detection Technologies for Trains and Highway Vehicles at Highway Rail Intersections 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Authors 8. Performing Organization Report No. Richard P. Reiff and Scott E. Gage, TTCI Anya A. Carroll and Jeffrey E. Gordon, Volpe Center DOT-VNTSC-FRA-03-02 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Transportation Technology Center, Inc. John A. Volpe National P.O. Box 11130 Transportation Systems Center 11. Contract or Grant No. Pueblo, CO 81001 55 Broadway DTFR53-93-C-00001 Task Order 123 Cambridge, MA 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13.