Forest Tenure Reform Implementation in Uganda CURRENT CHALLENGES and FUTURE OPPORTUNITIES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unlocking Future Investments in Uganda's Commercial Forest Sector

Uganda Unlocking future investments in Uganda’s commercial forest sector UNDERSTANDING THE IMPACTS OF TIMBER TRADE RESTRICTIONS ON THE PROFITABILITY OF PINE PLANTATION AND SAWMILL INVESTMENTS KEY MESSAGES EPIC } Supplies of pine produced by commercial plantations will increase rapidly over the next 5 years. y Pine plantations planted in the early 2000’s will soon mature, leading to an increase from roughly 200 000 m3 of pine production currently, to 800 000 m3 in 2023, and stabilizing at 1.2 million m3 after that. } Exporting timber from Uganda is impeded by restrictive policies. Numerous approval requirements and a lack of approved grading standards substantially hinder access to export licenses for timber. These restrictions are suppressing domestic prices relative to neighboring countries. } Trade restrictions hinder the profitability of commercial pine production. Based on average production costs and current domestic prices the Net Present Value of investment in commercial pine production ranges between negative USD 368 and negative USD 657 per hectare. } Removing export restrictions is critical to attract and sustain future investments in pine plantations and sawmilling. Access to higher prices offered in regional export markets contributes to a positive Net Present Value of pine plantation investments, in most scenarios, and a positive Net Present Value for investment in sawmilling. ECONOMIC AND POLICY ANALYSIS OF CLIMATE CHANGE OF CLIMATE ANALYSIS AND POLICY ECONOMIC The supply of pine from commercial plantations will rapidly increase over the next five years, but trade policy is lagging behind In 1990, 24 percent of Uganda was covered in natural forest. As a result of settlement and agricultural expansion, illegal logging, and charcoal production, natural forests in Uganda rapidly declined, reaching as low as nine percent of the country’s area in 2015. -

Land Reform and Sustainable Livelihoods

! M4 -vJ / / / o rtr £,/- -n AO ^ l> /4- e^^/of^'i e i & ' cy6; s 6 cy6; S 6 s- ' c fwsrnun Of WVELOPMENT STUDIES LIBRARY Acknowledgements The researchers would like to thank Ireland Aid and APSO for funding the research; the Ministers for Agriculture and Lands, Dr. Kisamba Mugerwa and Hon. Baguma Isoke for their support and contribution; and the Irish Embassy in Kampala for its support. Many thanks also to all who provided valuable insights into the research topic through interviews, focus group discussions and questionnaire surveys in Kampala and Kibaale District. Finally: a special word of thanks to supervisors and research fellows in MISR, particularly Mr Patrick Mulindwa who co-ordinated most of the field-based activities, and to Mr. Nick Chisholm in UCC for advice and direction particularly at design and analysis stages. BLDS (British Library for Development Studies) Institute of Development Studies Brighton BN1 9RE Tel: (01273) 915659 Email: [email protected] Website: www.blds.ids.ac.uk Please return by: Executive Summary Chapter One - Background and Introduction This report is one of the direct outputs of policy orientated research on land tenure / land reform conducted in specific areas of Uganda and South Africa. The main goal of the research is to document information and analysis on key issues relating to the land reform programme in Uganda. It is intended that that the following pages will provide those involved with the land reform process in Kibaale with information on: • how the land reform process is being carried out at a local level • who the various resource users are, how they are involved in the land reform, and how each is likely to benefit / loose • empirical evidence on gainers and losers (if any) from reform in other countries • the gender implications of tenure reform • how conflicts over resource rights are dealt with • essential supports to the reform process (e.g. -

Ghide Habtetsion Gebremichael the History and Discourse of Kachung

Ghide Habtetsion Gebremichael The History and Discourse of Kachung Forest View of Kachung plantation forest in 2016. Photo: Ghide Gebremichael Master’s thesis in Global Environmental History 1 “If we can really understand the problem, the answer will come out of it, because the answer is not separate from the problem.”(Jiddu Krishnamurti) 2 Abstract This study examined the history of the Kachung forest plantation in northern Uganda and associated environmental discourses. The forest, a project aimed at environmental protection and carbon offsetting, was designated a forest reserve in 1939 by the colonial government, as part of wider efforts to promote Ugandan timber for export and ensure their regeneration as a renewable resource. Since then, Kachung forest has been attributed different environmental significance by various actors, such as by the Uganda Forest Department, the Norwegian Agency for Development and Cooperation (NORAD), the Norwegian Afforestation Group (NAG) and presently by the Norwegian-based Green Resources company (GRAS). Between 1939 and 2006, the forest reserve underwent only limited changes in terms of management and composition. More radical change began in 2006, when GRAS started large- scale tree planting. In 2012, Kachung Forest was certified as a Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) project in accordance with the Kyoto Protocol. Since then, people living in and around the forest have been prevented from using forest resources for their livelihoods. They have expressed resistance to this by encroachment, setting fires in the forest and mounting angry protests against GRAS. One possible reason for this resistance is that afforestation took place with little prior knowledge of the forest’s history and value for local communities. -

Albertine Region Sustainable Development Project (Arsdp)

Republic of Uganda ALBERTINE REGION SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (ARSDP) RESETTLEMENT POLICY FRAMEWORK (RPF) VOLUME 1 FINAL DRAFT REPORT NOVEMBER 2013 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background The Government of Uganda (GoU) with support of the World Bank (IDA) is preparing the Albertine Region Sustainable Development Project. The Albertine Rift Valley is a center for rapid growth which is likely to accelerate with the oil development underway in the region. To ensure that the benefits of the oil development reach the residents of the area, GoU is keen to improve connectivity to and within the region and local economic infrastructure. The two Districts of Buliisa and Hoima are the focus of the project as well as the Town Council of Buliisa. Hoima Municipality is already included in the USMID project, which is shortly to commence, and is thus not included in the ARSDP. Project Components The Project has three components which are outlined below. Component 1. upgrading of 238km of Kyenjojo-Kabwoya-Hoima-Masindi-Kigumba is to be funded by both the AfDB (138km) and The World Bank (IDA) (100km). The RAP for this component has already been prepared, comments reviewed by the Bank and an update of PAPs and property is on going therefore this RPF does not cover component 1. The project coverage for component 2 and 3 will be as described below but in the event that additional districts are added under component 2 and any additioanl technical colleges are added under component 3 this RPF will apply. Component 1: Regional Connectivity: Improvement of the Kyenjojo-Kabwoya-Hoima- Kigumba National Road. -

Forests, Livelihoods and Poverty Alleviation: the Case of Uganda Forests, Livelihoods and Poverty Alleviation: the Case of Uganda

Forests, livelihoods and poverty alleviation: the case of Uganda Forests, livelihoods and poverty alleviation: the case of Uganda G. Shepherd and C. Kazoora with D. Mueller Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2013 The Forestry Policy and InstitutionsWorking Papers report on issues in the work programme of Fao. These working papers do not reflect any official position of FAO. Please refer to the FAO Web site (www.fao.org/forestry) for official information. The purpose of these papers is to provide early information on ongoing activities and programmes, to facilitate dialogue and to stimulate discussion. The Forest Economics, Policy and Products Division works in the broad areas of strenghthening national institutional capacities, including research, education and extension; forest policies and governance; support to national forest programmes; forests, poverty alleviation and food security; participatory forestry and sustainable livelihoods. For further information, please contact: Fred Kafeero Forestry Officer Forest Economics, Policy and Products Division Forestry Department, FAO Viale Delle terme di Caracalla 00153 Rome, Italy Email: [email protected] Website: www.fao.org/forestry Comments and feedback are welcome. For quotation: FAO.2013. Forests, Livelihoods and Poverty alleviation: the case of Uganda, by, G. Shepherd, C. Kazoora and D. Mueller. Forestry Policy and Institutions Working Paper No. 32. Rome. Cover photo: Ankole Cattle of Uganda The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression af any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Financial Inclusion for Refugees (FI4R) Results of Baseline Survey

Financial Inclusion for Refugees (FI4R) Results of baseline survey March 2020 Project Overview The Financial Inclusion for Refugees Project (FI4R) was launched by FSD Uganda and FSD Africa to support financial service providers (FSPs) to oer financial services to refugees and host communities. In addition, the project in collaboration with BFA Global will conduct refugee financial diaries in Uganda and provide insights into the financial strategies employed by refugees over time to build their livelihoods and manage their finances. The FSP partners in the project are Equity Bank Uganda Limited (EBUL), VisionFund Uganda (VFU) and Rural Finance Initiative (RUFI). They will oer bank accounts services for savings, remittances, transactions etc, loans to entrepreneurs, farmers and businesses as well as create jobs by recruiting agents and field sta. This is expected to build resilience, drive access to and use of basic financial services for refugees and host communities. Baseline Objectives • Provide the financial service providers in the FI4R project details of the relevant customer base they are targeting. • Provide other stakeholders one of the few in-depth surveys that covers financial tools, as well as income, expenditures and physical assets of a diverse set of refugees. Map of Settlements Covered Bidibidi SOUTH SUDAN Moyo Kaabong Lamwo *160,000 UGX Koboko Yumbe Obongi Kitgum Maracha Adjumani Arua Amuru Palorinya Kotido Gulu *90,417 UGXPader Agago Moroto Omoro Abim Nwoya Zombo Pakwach Otuke Nebbi Napak DEMOCRATIC Kole Oyam REPUBLIC Kapelebyong -

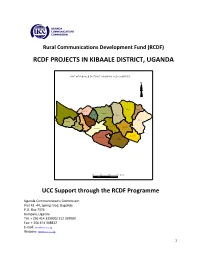

Rcdf Projects in Kibaale District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN KIBAALE DISTRICT, UGANDA MAP O F KIBAAL E DISTRIC T SHO WIN G SUB CO UNTIES N N alwe yo Kisiita R uga sha ri M pee fu Kiry a ng a M aba al e Kakin do Nko ok o Bw ika ra Ky an aiso ke Kag ad i M uho ro Kyeb an do Kasa m by a M uga ra m a Kib aa le TC Bwan s wa Bw am iram ira M atale 10 0 10 20 Kms UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..………....……3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….….…..……4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….….………..4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……...5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Kibaale district………….………..….5 2- Map of Uganda showing Kibaale district………..………………….………...……..….14 10- Map of Kibaale district showing sub counties………..…………………………..….15 11- Table showing the population of Kibaale district by sub counties…………..15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Kibaale district…………………………………….…….……..16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. -

University of Copenhagen

Drivers of forests and tree-based systems for food security and nutrition Kleinschmit, Daniela ; Sijapati Basnett, Bimbika ; Martin, Adrian; Rai, Nitin D.; Smith-Hall, Carsten; Dawson, Neil M.; Hickey, Gordon; Neufeldt, Henry; Ojha, Hemant R. ; Walelign, Solomon Zena Published in: Forests, trees and landscapes for food security and nutrition Publication date: 2015 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Kleinschmit, D., Sijapati Basnett, B., Martin, A., Rai, N. D., Smith-Hall, C., Dawson, N. M., Hickey, G., Neufeldt, H., Ojha, H. R., & Walelign, S. Z. (2015). Drivers of forests and tree-based systems for food security and nutrition. In B. Vira, C. Wildburger, & S. Mansourian (Eds.), Forests, trees and landscapes for food security and nutrition: a global assessment report (pp. 87-110). International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO). IUFRO world series Vol. 33 http://www.iufro.org/fileadmin/material/publications/iufro- series/ws33/ws33.pdf Download date: 27. sep.. 2021 IUFRO World Series Volume 33 Volume Series World IUFRO IUFRO World Series Volume 33 – Forests, Trees and Landscapes for Food Security and Nutrition Food for and Landscapes Trees 33 – Forests, Volume Series World IUFRO Forests, Trees and Landscapes for Food Security and Nutrition A Global Assessment Report Editors: Bhaskar Vira, Christoph Wildburger, Stephanie Mansourian 2015 IUFRO World Series Vol. 33 Forests, Trees and Landscapes for Food Security and Nutrition A Global Assessment Report Editors: Bhaskar Vira, Christoph Wildburger, Stephanie Mansourian Funding support for this publication was provided by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Finland, the United States Forest Service, and the Austrian Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, Environment and Water Management. -

Roads Sub-Sector Semi-Annual Budget Monitoring Report

Roads Sub-Sector Semi-Annual Budget Monitoring Report Financial Year 2018/19 April 2019 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O. Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... iii ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ...................................................................................... vi FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................................. iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................... v CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Background .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Roads Sub-sector Mandate ....................................................................................................... 1 1.2.1 Sub-sector Objectives and Priorities ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 Rationale/Purpose ..................................................................................................................... 2 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................. 3 2.1 Scope ........................................................................................................................................ -

Forestry and Macroeconomic Accounts of Uganda

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Ministry of Water and Environment. Forestry and Macroeconomic Accounts of Uganda: The Importance of Linking Ecosystem Services to Macroeconomics May 2018 Uganda Forest Technical Report Preamble and Acknowledgements This report summarises work conducted by the Uganda UN-REDD+ National programme during 2017 to guide the development of policy instruments for the Government of Uganda in order to evaluate the contribution of forests to the economy. The work conducted comprised economic modelling and analysis with the purpose of valuing the benefits of forest ecosystem services. The preliminary results presented here have not been verified by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and the National Forestry Authority (NFA), hence the ecosystem service valuations and policy Authors: recommendations are subject to change. Dr. Thierry De Oliveira UN Environment The work was highly reliant on data collection within Uganda. The UN-REDD+ National Programme, United Nations [email protected] Development Programme, UN Environment, the Uganda REDD+ secretariat and the authors wish to sincerely thank the Government departments and agencies as well as the Civil Society organizations which contributed to and supported Dr Jackie Crafford, Mr Nuveshen Naidoo, Mr Valmak Mathebula, Mr Joseph Mulders, this study. Special recognition goes to the team from the Uganda Bureau of Statistics, who provided valuable guidance Ms. Dineo Maila and Mr Kyle Harris and inputs during the study. Prime Africa, South Africa This study would not have been possible without the support of the staff from the IUCN Uganda country office, who [email protected] coordinated and steered this study on behalf of UN Environment. -

KIBAALE DISTRICT Hydrogeological Characteristics Map Inferred Static

KIBAALE DISTRICT THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Hydrogeological Characteristics Map EU Water Facility Ministry of Water and Environment # # # # # # # ## # # # # # ## ## # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # ## " # ## " # ## # # ## # # # " # # " # # # # # # # # # # DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC # # DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC # # # OF CONGO # OF CONGO # ## # # ## # " " Location of Kibaale District " # # " # # Inferred First Water Strike # Inferred Main Water Strike # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # South Sudan # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # " # " # # # # # # # # # # # #" #" " # # # # " # # # # # HOIMA # HOIMA " " # # " " # # # # Kyangwali # # Kyangwali # # # " # " # # # # Kikonda # Kikonda Kasungwa # # Kasungwa # Lake Alber # " Kitaganya # Central Forest Reserve Lake Alber " Kitaganya Central Forest Reserve # " # " # River Kafu # River Kafu # # # # # # # # # KYANKWANZI # # KYANKWANZI Ü # Ka#sambya # Ka#sambya " # " Ü # # # # # # # # # # # # ## Karama # # # # Karama # # " # " # # ## ## # # # # # # # Kasenyi # # Kasenyi # # Bugoma " # # # # # # Bugoma " # # # # # Democratic Republic of Congo # Central Forest Reserve # # Central Forest Reserve # # # # # # # # # # # # # # Buruko Buruko # # # # # # # # Kyamurangi #" # Kyamurangi #" # # # # # # # # Central Forest Reserve # # Nyarweyo Central Forest Reserve # # Nyarweyo # # ##" # Kyekadu Lake Albert # # ##" # Kyekadu # "# # "# Uganda Kasato # # # Kasato # # # NTOROKO Lake Albert # # # NTOROKO # # # Central Forest Reserve # # # # Central Forest Reserve # # # # Bira Rwengeye # # # Bira -

Effectiveness of Internship in Fostering Learning: the Case of African Rural University

Psychology Research, January 2016, Vol. 6, No. 1, 32-41 doi:10.17265/2159-5542/2016.01.004 D DAVID PUBLISHING Effectiveness of Internship in Fostering Learning: The Case of African Rural University Florence Ndibuuza African Rural University, Kagadi-Kibaale, Uganda Internship is deemed to be a prerequisite for a 21st Century graduate to survive in the world of work. It’s on the basis of this that this study sought to establish the effectiveness of internship in respect to learning in the field among undergraduates of African Rural University. The quantitative survey involved 23 students and 53 community members who filled a questionnaire and an interview guide respectively. Data analysis involved the use of percentages, means and multiple regression. The results of the study revealed that the three independent variables: cognitive, behavioral, and environmental learning experience (CLE, BLE and ELE) were not correlates of internship. It’s upon this background that it was recommended that the key players of the university ought to lay undue emphasis on enhancing CLE, BLE, and ELE, rather effort should be put on other elements to learning. Keywords: internship, learning, cognitive, behavioral and environmental experience Introduction Internship has been associated with several benefits to all key concerned stakeholders including the intern, academic institution and the employer. Accordingly studies (e.g., Steffen, 2010; Bukaliya, 2012; Papadimitriou, 2014) highlighted that internship provides authentic work experience to students. The institution is said to benefit through the increased cooperation and rapport with the internship organization, Bukaliya (2012) yet (Neugebauer, 2009; Steffen, 2010) mentioned that many employers use internship as the main tool for recruiting new talent.