Postgraduate Voices in Punk Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TCUJ Elections Held Today Bylaurenheist of Students Who Have Run in the for Us to Run Back and Forth to the Daily Editorial Board Past

THE DAILY Thursday, Februarys 20,1997 Volume XXXIV, Number 22 -b )WhereYou Read It First IC Reitman First merchant set to discusses accept points Monday disciplinary College Pizza wiring ends four-month wait by JOHN O’KEEFE wait. I think it’s a great boost for everyone verdicts Daily Editorial Board concerned, especially the students. They’ve The first of four restaurants to join the been waiting for this for a long time,” Sacca byTARASHINGLE off-campuspoints program will begin using said. Daily Staff Writer the debit-card system next week, nearly The program will allow students to use The Tufts Community Union Judiciary four months after the original kickoff date, their Tufts IDSmuch like a debit card when Panel has closed two disciplinary cases the director of dining services said yester- ordering food from any ofthe participating pending from last semester, said Associate day. merchants. Dean of Students Bruce Reitmzn. Patti Lee, who has coordinatedthe long- Themoneywillbededucted immediately One white student, whom the TCUJ awaited Merchants On Points program for from the student’s points account. Money found guilty of “racial harassment without the University, said she expects to install can be added to this account anytime dur- clear intent,” will spend this semester on the necessary equipment at College Pizza ing the year in $25 increments. Probation Level 11. In addition, the student on Friday and to have the system operating Unlike cash or credit-card payments, must complete 75 hours of community ser- there on Monday. bills paid with points are exempt from the vice and undergo alcohol abuse counsel- The other three restaurants in the pro- state’s five percent meal tax because the ing. -

Smash Hits Volume 34

\ ^^9^^ 30p FORTNlGHTiy March 20-Aprii 2 1980 Words t0^ TOPr includi Ator-* Hap House €oir Underground to GAR! SKias in coioui GfiRR/£V£f/ mjlt< H/Kim TEEIM THAT TU/W imv UGCfMONSTERS/ J /f yO(/ WOULD LIKE A FREE COLOUR POSTER COPY OF THIS ADVERTISEMENT, FILL IN THE COUPON AND RETURN IT TO: HULK POSTER, PO BOXt, SUDBURY, SUFFOLK C010 6SL. I AGE (PLEASE TICK THE APPROPRIATE SOX) UNDER 13[JI3-f7\JlS AND OVER U OFFER CLOSES ON APRIL 30TH 1980 ALLOW 28 DAYS FOR DELIVERY (swcKCAmisMASi) I I I iNAME ADDRESS.. SHt ' -*^' L.-**^ ¥• Mar 20-April 2 1980 Vol 2 No. 6 ECHO BEACH Martha Muffins 4 First of all, a big hi to all new &The readers of Smash Hits, and ANOTHER NAIL IN MY HEART welcome to the magazine that Squeeze 4 brings your vinyl alive! A warm welcome back too to all our much GOING UNDERGROUND loved regular readers. In addition The Jam 5 to all your usual news, features and chart songwords, we've got ATOMIC some extras for you — your free Blondie 6 record, a mini-P/ as crossword prize — as well as an extra song HELLO I AM YOUR HEART and revamping our Bette Bright 13 reviews/opinion section. We've also got a brand new regular ROSIE feature starting this issue — Joan Armatrading 13 regular coverage of the independent label scene (on page Managing Editor KOOL IN THE KAFTAN Nick Logan 26) plus the results of the Smash B. A. Robertson 16 Hits Readers Poll which are on Editor pages 1 4 and 1 5. -

Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1St Edition)

R O C K i n t h e R E S E R V A T I O N Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1st edition). (text, 2004) Yngvar B. Steinholt. New York and Bergen, Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. viii + 230 pages + 14 photo pages. Delivered in pdf format for printing in March 2005. ISBN 0-9701684-3-8 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt (b. 1969) currently teaches Russian Cultural History at the Department of Russian Studies, Bergen University (http://www.hf.uib.no/i/russisk/steinholt). The text is a revised and corrected version of the identically entitled doctoral thesis, publicly defended on 12. November 2004 at the Humanistics Faculty, Bergen University, in partial fulfilment of the Doctor Artium degree. Opponents were Associate Professor Finn Sivert Nielsen, Institute of Anthropology, Copenhagen University, and Professor Stan Hawkins, Institute of Musicology, Oslo University. The pagination, numbering, format, size, and page layout of the original thesis do not correspond to the present edition. Photographs by Andrei ‘Villi’ Usov ( A. Usov) are used with kind permission. Cover illustrations by Nikolai Kopeikin were made exclusively for RiR. Published by Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. 401 West End Avenue # 3B New York, NY 10024 USA Preface i Acknowledgements This study has been completed with the generous financial support of The Research Council of Norway (Norges Forskningsråd). It was conducted at the Department of Russian Studies in the friendly atmosphere of the Institute of Classical Philology, Religion and Russian Studies (IKRR), Bergen University. -

Mythopoesis, Scenes and Performance Fictions: Two Case Studies (Crass and Thee Temple Ov Psychick Youth)

This is an un-peer reviewed and un-copy edited draft of an article submitted to Parasol. Mythopoesis, Scenes and Performance Fictions: Two Case Studies (Crass and Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth) Simon O’Sullivan, Goldsmiths College, London Days were spent in fumes from the copying machine, from the aerosols and inks of the ‘banner production department’ – bed sheets vanished – banners appeared, from the soldering of audio, video, and lighting leads. The place stank. The garden was strewn with the custom made cabinets of the group’s equipment, the black silk- emulsion paint drying on the hessian surfaces. Everything matched. The band logo shone silver from the bullet-proof Crimpeline of the speaker front. Very neat. Very fetching. Peter Wright (quoted in George Berger, The Story of Crass) One thing was central to TOPY, apart from all the tactics and vivid aspects, and that was that beyond all else we desperately wanted to discover and develop a system of practices that would finally enable us and like minded individuals to consciously change our behaviours, erase our negative loops and become focussed and unencumbered with psychological baggage. Genesis P-Orridge, Thee Psychick Bible In this brief article I want to explore two scenes from the late 1970s/1980s: the groups Crass (1977-84) and Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth (1981-). Both of these ‘performance fictions’ (as I will call them) had a mythopoetic character (they produced – or fictioned – their own world), perhaps most evident in the emphasis on performance and collective participation. They also involved a focus on self- determination, and, with that, presented a challenge to more dominant fictions and consensual reality more generally.1 1. -

Girls Like Us: Linder

Linder Sterling is a British These include her 13-hour artist and performer whose NICOLE EMMENEGGER improvised dance perfor- career spans the 1970s WORDS mance piece Darktown Cake- B Manchester punk scene to Y walk and her most recent her current collaborations work, The Ultimate Form, a with Tate St. Ives and The 'performance ballet' inspired Hepworth Centre in north- at the photographed by Barbara Hepworth, fea- west England. turing dancers from North- PORTRAITS PORTRAITS ern Ballet and costumes by She has worked in a variety B arbara Pam Hogg. of mediums – from music H B Y DEVIN (as singer/songwriter/gui- Ives St. Tate Museum in epworth We met at the The Barbican B tarist for post-punk band LAIR Centre in London on a crisp Ludus) and collage (using March morning, just days a steady scalpel to splice after the opening of her first pornographic images into big retrospective at Le Musée feminist statements), to her d’Art Moderne in Paris. current durational works. Linder 18 19 Nicole Emmenegger: First off, thank you for send- Yes, I used to have this fascination for the mid-fifties. People ing through the preparatory text about you and your I know at every age seem to have this fascination about the work. It ended up being ten pages in 10-point font! culture that you were born into, climbed into. It’s your own personal etymology and you have to go back and work it Linder: How strange, I don’t even enjoy writing! out. It’s good detective work. It makes sense and how lucky for you that 1976 was such a great year. -

Manic Street Preachers Tornano Con Un Nuovo Disco, Intitolato Futurology, in Uscita L'8 Manic Street Preachers Luglio 2014

LUNEDì 28 APRILE 2014 A soli nove mesi di distanza dall'acclamato Rewind The Film (top 5 nel Regno Unito), undicesimo album da studio della band, i Manic Street Preachers tornano con un nuovo disco, intitolato Futurology, in uscita l'8 Manic Street Preachers luglio 2014. Futurology, il nuovo album, in uscita l'8 luglio. Registrati ai leggendari Hansa Studios di Berlino e al Faster, lo studio dei In concerto in Italia il 2 giugno 2014 al RocK In Manics a Cardiff, i tredici brani che compongono l'album vedono la band Idro di Bologna gallese in forma smagliante, addirittura esplosiva. Uno stacco netto rispetto al disco precedente, ma sempre all'insegna di uno stile inconfondibile. LA REDAZIONE Il primo singolo estratto è "Walk Me To The Bridge", dalle chiare influenze europee. In una recente conversazione con John Doran di Quietus, Nicky Wire ha parlato del testo del brano, che ha cominciato a prendere forma qualche anno fa. "Qualcuno penserà che la canzone contenga tanti riferimenti a Richey Edwards, ma in realtà parla del ponte di Øresund che collega la Svezia alla Danimarca. Tanto tempo fa, quando [email protected] attraversavamo quel ponte, stavo perdendo entusiasmo per le cose e SPETTACOLINEWS.IT pensavo di lasciare la band (il "fatal friend"). 'Walk Me To The Bridge' parla dei ponti che ti consentono di vivere un'esperienza extracorporea quando lasci un luogo per raggiungerne un altro". Secondo James Dean Bradfield, il brano è "una canzone ideale per i viaggi in auto, dal sapore squisitamente europeo e carica di tensione emotiva, con sintetizzatori in stile primi Simple Minds e un assolo di chitarra Ebow alla 'Heroes'". -

American Foreign Policy, the Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Spring 5-10-2017 Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War Mindy Clegg Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Recommended Citation Clegg, Mindy, "Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/58 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MUSIC FOR THE INTERNATIONAL MASSES: AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY, THE RECORDING INDUSTRY, AND PUNK ROCK IN THE COLD WAR by MINDY CLEGG Under the Direction of ALEX SAYF CUMMINGS, PhD ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the connections between US foreign policy initiatives, the global expansion of the American recording industry, and the rise of punk in the 1970s and 1980s. The material support of the US government contributed to the globalization of the recording industry and functioned as a facet American-style consumerism. As American culture spread, so did questions about the Cold War and consumerism. As young people began to question the Cold War order they still consumed American mass culture as a way of rebelling against the establishment. But corporations complicit in the Cold War produced this mass culture. Punks embraced cultural rebellion like hippies. -

Punk Preludes

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Summer 8-1996 Punk Preludes Travis Gerarde Buck University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Buck, Travis Gerarde, "Punk Preludes" (1996). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/160 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Punk Preludes Travis Buck Senior Honors Project University of Tennessee, Knoxville Abstract This paper is an analysis of some of the lyrics of two early punk rock bands, The Sex Pistols and The Dead Kennedys. Focus is made on the background of the lyrics and the sub-text as well as text of the lyrics. There is also some analysis of punk's impact on mondern music During the mid to late 1970's a new genre of music crept into the popular culture on both sides of the Atlantic; this genre became known as punk rock. Divorcing themselves from the mainstream of music and estranging nlany on their way, punk musicians challenged both nlusical and cultural conventions. The music, for the most part, was written by the performers and performed without worrying about what other people thought of it. -

Progressive Poetics

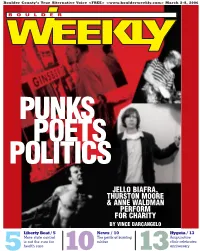

Boulder County’s True Alternative Voice <FREE> <www.boulderweekly.com> March 2-8, 2006 PUNKS POETS POLITICS JELLO BIAFRA, THURSTON MOORE & ANNE WALDMAN PERFORM FOR CHARITY BY VINCE DARCANGELO Liberty Beat / 5 News / 10 Hygeia / 13 More state control The perils of burning Acupuncture is not the cure for rubber clinic celebrates 5 health care 10 13 anniversary inside Page 21 / Overtones: Hip-hop eye exam buzzhttp://www.boulderweekly.com/buzzlead.html Page 26 / High Decibel: Sex convention blues Page 29 / Getting it on!: Sex holiday in Cambodia ProgressiveProgressive Page 35 / Screen: poeticspoetics Delapa handicaps the Oscars cutsbuzz Can’t-miss events for [ the upcoming week ] buzz Flogging Molly Thursday Greyboy Allstars—Sax legend Karl Denson delivers the funk, jazz and good-time boogaloo with the Greyboy Allstars. Fox Theatre, 1135 13th St., Boulder, 303-443-3399. was no holiday in Cambodia for Khyentse James when on Dec. Friday Art and activism 21, 2005, she drove her motorcycle into a 10-foot ditch at 90 Napalm Death—More than two decades mph, shattering her right leg into nine pieces. Though an experi- since defining the grindcore genre, Napalm enced biker, she was traversing a dangerous, barely accessible Death continues to assault America with its come together to Cambodian jungle in search of rarely seen temples. So remote was brash brand of heavy metal. Bluebird It Theatre, 3317 E. Colfax Ave., Denver, 303- the location that it took eight hours for help to arrive and another eight hours to benefit migrant deliver James to the nearest medical facility—a facility that was unable to treat 322-2308. -

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document cannot be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. 1 Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in established music trade publications. Please provide DotMusic with evidence that such criteria is met at [email protected] if you would like your artist name of brand name to be included in the DotMusic GPML. GLOBALLY PROTECTED MARKS LIST (GPML) - MUSIC ARTISTS DOTMUSIC (.MUSIC) ? and the Mysterians 10 Years 10,000 Maniacs © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document 10cc can not be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part 12 Stones without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. Visit 13th Floor Elevators www.music.us 1910 Fruitgum Co. 2 Unlimited Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. 3 Doors Down Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in 30 Seconds to Mars established music trade publications. Please -

Smash Hits Volume 36

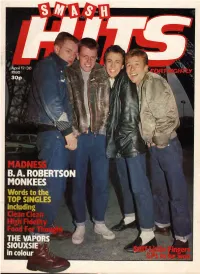

4pril 17-30 ^ 1980 m 30p 1 4. \ t, i% \ '."^.iiam 1 \ # »^» r ,:?^ ) ^ MARNF B. A. ROBERTSON NONKEES THE originals/ The Atlantic Masters — original soul music from the Atlantic label. Ten seven inch E.P.s, each with four tracks and at least two different artists. Taken direct from the original master tapes. Re-cut, Re-issued, Re-packaged. £1.60^ 11168 2 SMASH HITS April 17-30 1980 Vol 2 No. 8 WILL I HOLD IT right there! Now before WHAT DO WITHOUT YOU? you all write in saying how come Lene Lovich 4 there's only four of Madness on CLEAN CLEAN the cover, we'll tell ya. That heap of metalwork in the background The Buggies 5 IS none other than the Eiffel DAYDREAM BELIEVER Tower and the other trois {that's i'our actual French) scarpered off The Monkees 7 up it instead of having their photo MODERN GIRL taken. Now you know why Sheena Easton 8 they're called Madness! More nuttiness can be found on pages SILVER DREAM RACER 12 and 13, and other goodies in David Essex 14 this issue include another chance to win a mini-TV on the I'VE NEVER BEEN IN LOVE crossword, a binder offer for all Suzi Quatro 15 your back issues of Smash Hits CHECK OUT THE GROOVE (page 36), another token towards Mandging Editor your free set of badges (page 35) Nick Logan Bobby Thurston 19 and our great Joe Jackson SEXY EYES competition featuring a chance to Editor himself! (That's Dr. Hook 22 meet the man on Ian Cranna page 28). -

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel B.S. Physics Hobart and William Smith Colleges, 2004 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2008 © 2008 Evan Landon Wendel. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _______________________________________________________ Program in Comparative Media Studies May 9, 2008 Certified By: _____________________________________________________________ William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Accepted By: _____________________________________________________________ Henry Jenkins Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies 2 3 New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on May 9, 2008 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract This thesis explores the evolving nature of independent music practices in the context of offline and online social networks. The pivotal role of social networks in the cultural production of music is first examined by treating an independent record label of the post- punk era as an offline social network.