A Vafa Thesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

İNAN SİNEMASINDA KAİHN Fci1/'» Fimufrtv U J* Fatin Kanat

İNAN SİNEMASINDA KAİHN fci1/'» fimufrtv U j* Fatin Kanat İRAN SİNEMASINDA KADIN Kadın Temsili ve Kadın Yönetmenler IRAN SİNEMASINDA KADIN Kadın Temsili ve Kadın Yönetmenler © Dipnot Yayınlan Editör: Ahmet Gürata Kapak Tasarımı: İdil Tuncalı Dizgi ve Baskı Öncesi Hazırlık: Dipnot Bas. Yay. Ltd.Şti Dipnot Yayınları 38 Sinema Dizisi 2 1. Baskı 2007 / Ankara ISBN:978- 975-9051-44-0 Baskı: Mattek Matbaacılık Bas. Yay. Tan. Tic. San. Ldt Şti GMK Bulvan No 83 / 32 Maltepe/ Ankara Dipnot Yayınlan Selanik Cad. No: 82/32 Kızılay/ ANKARA Tel: (0 312) 4192932 ■ Faks: (0 312)4192532 E-posta: [email protected] Anneme, babama ve boyun eğmeyen tüm kadınlara İÇİNDEKİLER ÖNSÖZ- Nejat Ulusay............................................................................. 7 GİRİŞ........................................................................................................15 I.Böliim İRAN VE İSLAM: DEVRİM’İN GÖLGESİNDEKİ SİNEMA VE KADIN............................................................................21 1. Binbir Gece Masalları’nın Son Versiyonu............................... 21 2. İslam Devrimi............................................................................ 23 3. Devrim Öncesi İran Sineması................................................... 29 4. Devrim Sonrası Sinema............................................................ 33 5. Kurallarla Örülü ve Sınırlı bir Sinema: Sansür ve otosansür....35 6. Sistemin ve İran Sinemasının Başağnsı: Kadın.......................36 7. Maym Tarlasından Geçen Kadınlar......................................... -

Download File (Pdf; 3Mb)

Volume 15 - Number 2 February – March 2019 £4 TTHISHIS ISSUEISSUE: IIRANIANRANIAN CINEMACINEMA ● IIndianndian camera,camera, IranianIranian heartheart ● TThehe lliteraryiterary aandnd dramaticdramatic rootsroots ofof thethe IranianIranian NewNew WaveWave ● DDystopicystopic TTehranehran inin ‘Film‘Film Farsi’Farsi’ popularpopular ccinemainema ● PParvizarviz SSayyad:ayyad: socio-politicalsocio-political commentatorcommentator dresseddressed asas villagevillage foolfool ● TThehe nnoiroir worldworld ooff MMasudasud KKimiaiimiai ● TThehe rresurgenceesurgence ofof IranianIranian ‘Sacred‘Sacred Defence’Defence’ CinemaCinema ● AAsgharsghar Farhadi’sFarhadi’s ccinemainema ● NNewew diasporicdiasporic visionsvisions ofof IranIran ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews andand eventsevents inin LondonLondon Volume 15 - Number 2 February – March 2019 £4 TTHISHIS IISSUESSUE: IIRANIANRANIAN CCINEMAINEMA ● IIndianndian ccamera,amera, IIranianranian heartheart ● TThehe lliteraryiterary aandnd ddramaticramatic rootsroots ooff thethe IIranianranian NNewew WWaveave ● DDystopicystopic TTehranehran iinn ‘Film-Farsi’‘Film-Farsi’ ppopularopular ccinemainema ● PParvizarviz SSayyad:ayyad: ssocio-politicalocio-political commentatorcommentator dresseddressed aass vvillageillage ffoolool ● TThehe nnoiroir wworldorld ooff MMasudasud KKimiaiimiai ● TThehe rresurgenceesurgence ooff IIranianranian ‘Sacred‘Sacred DDefence’efence’ CinemaCinema ● AAsgharsghar FFarhadi’sarhadi’s ccinemainema ● NNewew ddiasporiciasporic visionsvisions ooff IIranran ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews aandnd eeventsvents -

Triumphs and Tragedies of the Iranian Revolution

The Road to Isolation: Triumphs and Tragedies of the Iranian Revolution Salma Schwartzman Senior Division Historical Paper Word Count: 2, 499 !1 Born of conflicting interests and influences — those ancient tensions deeply rooted in its own society — the Iranian revolution generated numerous and alternating cycles of triumph and tragedy, the one always inextricably resulting from and offsetting the other. This series of vast political shifts saw the nation shudder from a near feudal monarchy to a democratized state, before finally relapsing into an oppressive, religiously based conservatism. The Prelude: The White Revolution Dating from 1960 to 1963, the White Revolution was a period of time in Iran in which modernization, westernization, and industrialization were ambitiously promoted by the the country’s governing royalty: the Pahlavi regime. Yet although many of these changes brought material and social benefit, the country was not ready to embrace such a rapid transition from its traditional structure; thus the White Revolution sowed the seeds that would later blossom into the Iranian Revolution1. Under the reign of Reza Shah Pahlavi, the State of Iran underwent serious industrial expansion. After seizing almost complete political power for himself, the Shah set in motion the land reform law of 1962.2 This law forced landed minorities to surrender vast tracts of lands to the government so that it could be redistributed to small scale agriculturalists. The landowners who experienced losses were compensated through shares of state owned Iranian industries. Cultivators and laborers also received share holdings of Iranian industries and agricultural profits.3 This reform not only helped the agrarian community, but encouraged and supported 1 Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. -

Film & Event Calendar

1 SAT 17 MON 21 FRI 25 TUE 29 SAT Events & Programs Film & Event Calendar 12:00 Event 4:00 Film 1:30 Film 11:00 Event 10:20 Family Gallery Sessions Tours for Fours: Art-Making Warm Up. MoMA PS1 Sympathy for The Keys of the #ArtSpeaks. Tours for Fours. Daily, 11:30 a.m. & 1:30 p.m. Materials the Devil. T1 Kingdom. T2 Museum galleries Education & 4:00 Film Museum galleries Saturdays & Sundays, Sep 15–30, Research Building See How They Fall. 7:00 Film 7:00 Film 4:30 Film 10:20–11:15 a.m. Join us for conversations and T2 An Evening with Dragonfly Eyes. T2 Dragonfly Eyes. T2 10:20 Family Education & Research Building activities that offer insightful and Yvonne Rainer. T2 A Closer Look for 7:00 Film 7:30 Film 7:00 Film unusual ways to engage with art. Look, listen, and share ideas TUE FRI MON SAT Kids. Education & A Self-Made Hero. 7:00 Film The Wind Will Carry Pig. T2 while you explore art through Research Building Limited to 25 participants T2 4 7 10 15 A Moment of Us. T1 movement, drawing, and more. 7:00 Film 1:30 Film 4:00 Film 10:20 Family Innocence. T1 4:00 Film WED Art Lab: Nature For kids age four and adult companions. SUN Dheepan. T2 Brigham Young. T2 This Can’t Happen Tours for Fours. SAT The Pear Tree. T2 Free tickets are distributed on a 26 Daily. Education & Research first-come, first-served basis at Here/High Tension. -

Persian Heri Tage

Persian Heri tage Persian Heritage Vol. 24, No. 93 Spring 2019 www.persian-heritage.com Persian Heritage, Inc. FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK 6 110 Passaic Avenue The First Annual Iranian Film Festival New York 7 Passaic, NJ 07055 E-mail: [email protected] LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 8 Telephone: (973) 471-4283 Fax: 973 471 8534 NEWS Gold for Iran’s Para Shooter, Sareh Javanmardi 10 EDITOR Resket Tower in Sari, Iran 11 SHAHROKH AHKAMI EDITORIAL BOARD COMMENTARY Dr. Mehdi Abusaidi, Shirin Ahkami Raiszadeh, Dr. Mahvash Alavi Naini, Who Owns Iran’s Oil? 12 Mohammad Bagher Alavi, Dr. Talat Bassari, Mohammad H. Hakami, (Khosrow B. Semnani) Ardeshir Lotfalian, K. B. Navi, Dr. Kamshad Raiszadeh, Farhang A. Sadeghpour, Mohammad K. Sadigh, THE ARTS & CULTURE M. A. Dowlatshahi. REVIEWS 15 MANAGING EDITOR Professor Dariush Borbor’s Works 16 HALLEH NIA (Kaveh Farrokh) ADVERTISING Uncle’s Complaint: Tale of Rejuvenation 17 HALLEH NIA (Iraj Bashiri) * The contents of the articles and ad ver tisements in this journal, with the ex ception The Sakas (Michael McClain) 20 of the edi torial, are the sole works of each The Patriots Who Triggered Demise of the Empire 23 in di vidual writers and contributors. This maga zine does not have any confirmed knowledge (M. Reza Vaghefi) as to the truth and ve racity of these articles. all contributors agree to hold harmless and An Interview with J. Golestan-Parast and R. Blake 25 indemnify Persian Heri tage (Mirass-e Iran), Persian Heritage Inc., its editors, staff, board (Brian Appleton) of directors, and all those in di viduals di rectly Reza Abdoh 29 associated with the publishing of this maga zine. -

The Iranian Revolution in 1979

Demonstrations of the Iranian People’s Mujahideens (Warriors) during the Iranian Revolution in 1979. Dr. Ali Shariati, an Iranian leftist on the left. Ayatollah Khomeini on the right. The Iranian Revolution Gelvin, ch. 17 & 18 & other sources, notes by Denis Bašić The Pahlavi Dynasty • could hardly be called a “dynasty,” for it had only two rulers - Reza Shah Pahlavi (ruled 1926-1941) and his son Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi (ruled 1941-1979). • The son came to power after his father was deposed by the Allies (the Russian and British forces) due to his alliance with the Nazi Germany. • The Allies reestablished the majlis and allowed the organization of trade unions and political parties in order to limit the power of the new shah and to prevent him from following his father’s independence course. • Much to the chagrin of the British and Americans, the most popular party proved to be Tudeh - the communist party with more than 100,000 members. • The second Shah’s power was further eroded when in 1951 Muhammad Mossadegh was elected the prime minister on a platform that advocated nationalizing the oil industry and restricting the shah’s power. • Iranian Prime Minister 1951–3. A prominent parliamentarian. He was twice Muhammad appointed to that office by Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, after a Mossadegh positive vote of inclination by the 1882-1967 parliament. Mossadegh was a nationalist and passionately opposed foreign intervention in Iran. He was also the architect of the nationalization of the Iranian oil industry, which had been under British control through the Anglo- Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), today known as British Petroleum (BP). -

Full List of Book Discussion Kits – September 2016

Full List of Book Discussion Kits – September 2016 1776 by David McCullough -(Large Print) Esteemed historian David McCullough details the 12 months of 1776 and shows how outnumbered and supposedly inferior men managed to fight off the world's greatest army. Abraham: A Journey to the Heart of Three Faiths by Bruce Feiler - In this timely and uplifting journey, the bestselling author of Walking the Bible searches for the man at the heart of the world's three monotheistic religions -- and today's deadliest conflicts. Abundance: a novel of Marie Antoinette by Sena Jeter Naslund - Marie Antoinette lived a brief--but astounding--life. She rebelled against the formality and rigid protocol of the court; an outsider who became the target of a revolution that ultimately decided her fate. After This by Alice McDermott - This novel of a middle-class American family, in the middle decades of the twentieth century, captures the social, political, and spiritual upheavals of their changing world. Ahab's Wife, or the Star-Gazer by Sena Jeter Naslund - Inspired by a brief passage in Melville's Moby-Dick, this tale of 19th century America explores the strong-willed woman who loved Captain Ahab. Aindreas the Messenger: Louisville, Ky, 1855 by Gerald McDaniel - Aindreas is a young Irish-Catholic boy living in gaudy, grubby Louisville in 1855, a city where being Irish, Catholic, German or black usually means trouble. The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho - A fable about undauntingly following one's dreams, listening to one's heart, and reading life's omens features dialogue between a boy and an unnamed being. -

Fourth Plenary Meeting Quatrième Séance Plénière

A62/VR/4 page 75 FOURTH PLENARY MEETING Tuesday, 19 May 2009, at 14:35 President: Mr N.S. DE SILVA (Sri Lanka) later: Mr A.M. FOUDA (Cameroon) QUATRIÈME SÉANCE PLÉNIÈRE Mardi 19 mai 2009, 14 h 35 Président : M. N.S. DE SILVA (Sri Lanka) puis : M. A.M. FOUDA (Cameroun) 1. INVITED SPEAKERS INTERVENANTS INVITÉS The PRESIDENT: Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen. The Health Assembly will now take up consideration of item 4 of the Agenda; Invited speakers. It is an honour for me to welcome, on behalf of this Health Assembly, our first invited speaker, the Eighth Secretary-General of the United Nations, Mr Ban Ki-moon. I think he needs no introduction but it is my duty to introduce him. From his earliest days in office, the Secretary-General has identified global health as one of his top priorities. He has been working to strengthen the United Nations system and he has reached out to foundations, research centres, civil society and the private sector to help build partnerships to advance the cause of global public health. The Secretary-General has been a consistent voice for the health needs of the poorest and the most vulnerable – especially at a time of economic crisis. He has been a leading advocate for women’s health. In the face of the outbreak of influenza A (H1N1) 2009, he has been a strong voice of support for WHO’s leadership and coordination efforts. His presence here is another demonstration of his commitment to the cause that brings us together – the advancement of global public health for all. -

2011 Fargo Film Festival Program

1 AROUND THE WORLD IN 11 YEARS... COMING FULL CIRCLE... Dear Fargo Film Festival Audiences, On March 1, 2001 an intrepid band of film lovers held our collective breaths as we waited for the press to show up for the opening press conference of our very first Fargo Film Festival. The press arrived as did award winning filmmakers Rob Nilson and John Hanson to celebrate the screening of their North Dakota-produced and Cannes Film Festival award winner, Northern Lights. On opening night, March 1, 2011, the Fargo Film Festival again celebrates North Dakota culture, history, and film making with The Lutefisk Wars and Roll Out, Cowboy. Over the years, our festival journey has circled the globe from Fargo to Leningradsky to Rwanda to Antarctica, all without leaving the cushy seats of our very own hometown Fargo Theatre. Some of you have been my traveling companions from the very Margie Bailly Emily Beck FARGO THEATRE FARGO THEATRE beginning of this 11 year cinematic tour. Including Fargo Film Festival 2011 Volunteer Spirit Award Winner, Marty Jonason. Executive Director Film Programmer My heartfelt thanks! Whether you are a long-time film traveler or just beginning your festival journey, “welcome aboard”. In 2012, Fargo Theatre Film Programmer Emily Beck will take over as your festival tour guide. You will be in very good hands. You’ll find me in the front row of the balcony “tripping out” on massive amounts of popcorn and movies, movies, movies. Margie Bailly EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR • HISTORIC FARGO THEATRE DAN FRANCIS PHOTOGRAPHY FARGO THEATRE STAFF: -

Truce Agreement Victory for Yemeni Nation: Abdulsalam

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 16 Pages Price 20,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 39th year No.13278 Saturday DECEMBER 15, 2018 Azar 23, 1397 Rabi’ Al thani 6, 1440 We should make Iranian scientist Persepolis beat Pars “Dark Room” sanctions ineffective: Baharvand among winners Jonoubi, Tractor Sazi named best at general 2 of 2019 TWAS Prize 9 beaten by Foolad: IPL 15 Kerala film festival 16 Iran to deal with CNPC according Truce agreement victory for to contract rights: Zanganeh ECONOMY TEHRAN — Irani- contract, when Total left they were to take deskan Oil Minister Bijan over based on the terms of the contract Namdar Zanganeh said CNPC’s leaving otherwise it would be a breach of contract South Pars deal would be a violation of and we will deal with it according to our Yemeni nation: Abdulsalam the contract and Iran will act accordingly, contractual rights. IRNA reported. Earlier in November, Zanganeh had Iran welcomes preliminary deals between Yemeni warring sides 2 In an interview with the national said that China’s state-owned CNPC television on Wednesday, the official had officially replaced France’s Total noted that since the Chinese company in Iran’s multibillion-dollar South Pars is the second biggest shareholder in the gas project. 4 See page 13 Zarif says Iran gets its security from people POLITICS TEHRAN – Foreign he said in speech at annual gathering deskMinister Mohammad of pro-reform Neda-ye Iranian Party Javad Zarif said on Friday that it is (Voice of Iranians). -

It All Begins with Glass

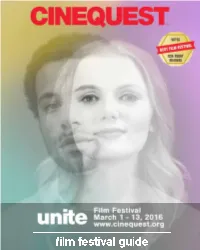

film festival guide IT ALL BEGINS WITH GLASS The selection of a lens is the moment that can defi ne a shoot. From Hollywood studios to exotic locations around the globe, amazing big screen content is dramatized every day through the selection of Canon cinema lenses. The technologies behind our PL and EF mount cinema lenses ensure clear, crisp motion capture to the most demanding shoots. Canon optics empower fi lmmakers to bring visions to life. Throughout the more than 75 years of Canon history, it’s why we’ve always placed Glass First. glassfi rst.com GLASS FIRST © 2015 Canon U.S.A., Inc. All rights reserved. Canon is a registered trademark of Canon Inc. in the United States and may also be a registered trademark or trademark in other countries. Canon_Glass First Ad_CINEQUEST 2016.indd 1 1/7/16 3:03 PM WELCOME unite at Film Festival! Join forces with eye in the sky artists, film lovers, and innova- pg 7 tors—from across the globe, from all walks of life. Experience the com- pelling power of ONE, through films, media innovations, events, and celebrations. Embrace old friend- james franco ships, create new pg 17 connections, band together. Radiate outward, forging original pathways into the future. Emerge as a close-knit community, bound by fresh and fortified fellowship, collaboration, inspiration, vision, rita moreno and creativity. Come together…Unite! pg 25 CINEQUEST FILM FESTIVAL 2016 MARCH 1 - 13 CINEQUEST FILM FESTIVAL PICTURE THE POSSIBILITIES CINEQUEST MAVERICKS STUDIO showcases premiere films, empowers global youth with the creates innovative and renowned and emerging artists, tools, confidence, and inspiration motion pictures, television, and and breakthrough technology— to form and create their dreams distribution paradigms. -

The Veiling Issue in 20Th Century Iran in Fashion and Society, Religion, and Government

Article The Veiling Issue in 20th Century Iran in Fashion and Society, Religion, and Government Faegheh Shirazi Department of Middle Eastern Studies, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA; [email protected] Received: 7 May 2019; Accepted: 30 July 2019; Published: 1 August 2019 Abstract: This essay focuses on the Iranian woman’s veil from various perspectives including cultural, social, religious, aesthetic, as well as political to better understand this object of clothing with multiple interpretive meanings. The veil and veiling are uniquely imbued with layers of meanings serving multiple agendas. Sometimes the function of veiling is contradictory in that it can serve equally opposing political agendas. Keywords: Iran; women’s right; veiling; veiling fashion; Iranian politics Iran has a long history of imposing rules about what women can and cannot wear, in addition to so many other forms of discriminatory laws against women that violate human rights. One of the most recent protests (at Tehran University) against the compulsory hijab1 was also meant to unite Iranians of diverse backgrounds to show their dissatisfaction with the government. For the most part, the demonstration was only a hopeful attempt for change. In one tweet from Iran [at Tehran University] we read in Persian: When Basijis [who receive their orders from the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Supreme Leader of Iran] did not give permission to the students to present a talk against compulsory hijab, the students started to sing together the iconic poem of yar e ,my school friend2. “Basij members became helpless and nervous/ﻳﺎﺭ ﺩﺑﺴﺘﺎﻧﯽ ﻣﻦ dabestani man but the students sang louder and louder.