The Case of Pewdiepie's Youtube Community As a Space for Right-Wing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

Practical Applications of Affinity Spaces for English

Running head: HARNESSING WRITING IN THE WILD 1 Harnessing Writing in the Wild: Practical Applications of Affinity Spaces for English Language Instruction Marta Dominika Halaczkiewicz Utah State University Abstract In this article I aim to explore ways in which affinity spaces (Gee, 2004) can be adapted for English language instruction. Affinity spaces attract participants who enthusiastically share their passions, such as popular culture, video games, or literature. Researchers have found that affinity spaces contribute to improvements in reading (Steinkuehler, Compton- Lilly, & King, 2010) and writing (Black, 2007) literacy of both native English speakers and ELLs. Previous research has explored applications of these spaces in language instruction including incorporating topics from popular culture in courses and engaging students in online writing (Sauro & Sundmark, 2016). Other adaptations used the online content of affinity spaces as materials for language analysis in the classroom (Thorne & Reinhardt, 2008). I break down the characteristics of affinity spaces (Gee & Hayes, 2012) and propose them as a framework aimed to harness the benefits of affinity spaces for English language classroom adaptation. These practical applications include student- selected course activity topics, sharing student writing online, and taking on leadership roles in an online environment. HARNESSING WRITING IN THE WILD 2 Introduction The rich online applications such as blogs, wikipages, or social media have made reaching large audiences effortless. These online platforms have encouraged many aspiring authors to share their ideas. In fact, writers have been so prolific online that research attempts commenced to study these literacy practices (Gee, 2004; Howard, 2014; Thorne & Reinhardt, 2008). The New Literacy Studies (Howard, 2014) look at how people connect online and how, through active participation, they become authors and consumers of content. -

Youtube 1 Youtube

YouTube 1 YouTube YouTube, LLC Type Subsidiary, limited liability company Founded February 2005 Founder Steve Chen Chad Hurley Jawed Karim Headquarters 901 Cherry Ave, San Bruno, California, United States Area served Worldwide Key people Salar Kamangar, CEO Chad Hurley, Advisor Owner Independent (2005–2006) Google Inc. (2006–present) Slogan Broadcast Yourself Website [youtube.com youtube.com] (see list of localized domain names) [1] Alexa rank 3 (February 2011) Type of site video hosting service Advertising Google AdSense Registration Optional (Only required for certain tasks such as viewing flagged videos, viewing flagged comments and uploading videos) [2] Available in 34 languages available through user interface Launched February 14, 2005 Current status Active YouTube is a video-sharing website on which users can upload, share, and view videos, created by three former PayPal employees in February 2005.[3] The company is based in San Bruno, California, and uses Adobe Flash Video and HTML5[4] technology to display a wide variety of user-generated video content, including movie clips, TV clips, and music videos, as well as amateur content such as video blogging and short original videos. Most of the content on YouTube has been uploaded by individuals, although media corporations including CBS, BBC, Vevo, Hulu and other organizations offer some of their material via the site, as part of the YouTube partnership program.[5] Unregistered users may watch videos, and registered users may upload an unlimited number of videos. Videos that are considered to contain potentially offensive content are available only to registered users 18 years old and older. In November 2006, YouTube, LLC was bought by Google Inc. -

Disturbed Youtube for Kids: Characterizing and Detecting Inappropriate Videos Targeting Young Children

Proceedings of the Fourteenth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2020) Disturbed YouTube for Kids: Characterizing and Detecting Inappropriate Videos Targeting Young Children Kostantinos Papadamou, Antonis Papasavva, Savvas Zannettou,∗ Jeremy Blackburn,† Nicolas Kourtellis,‡ Ilias Leontiadis,‡ Gianluca Stringhini, Michael Sirivianos Cyprus University of Technology, ∗Max-Planck-Institut fur¨ Informatik, †Binghamton University, ‡Telefonica Research, Boston University {ck.papadamou, as.papasavva}@edu.cut.ac.cy, [email protected], [email protected] {nicolas.kourtellis, ilias.leontiadis}@telefonica.com, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract A large number of the most-subscribed YouTube channels tar- get children of very young age. Hundreds of toddler-oriented channels on YouTube feature inoffensive, well produced, and educational videos. Unfortunately, inappropriate content that targets this demographic is also common. YouTube’s algo- rithmic recommendation system regrettably suggests inap- propriate content because some of it mimics or is derived Figure 1: Examples of disturbing videos, i.e. inappropriate from otherwise appropriate content. Considering the risk for early childhood development, and an increasing trend in tod- videos that target toddlers. dler’s consumption of YouTube media, this is a worrisome problem. In this work, we build a classifier able to discern inappropriate content that targets toddlers on YouTube with Frozen, Mickey Mouse, etc., combined with disturbing con- 84.3% accuracy, and leverage it to perform a large-scale, tent containing, for example, mild violence and sexual con- quantitative characterization that reveals some of the risks of notations. These disturbing videos usually include an inno- YouTube media consumption by young children. Our analy- cent thumbnail aiming at tricking the toddlers and their cus- sis reveals that YouTube is still plagued by such disturbing todians. -

C9268c Baylor.B

Driving North 1981 COLLEGIUM Let me have the grace to speak of this for I would mind what happens here. — Robert Duncan collegium The darkness was Protestant that year, but not A Publication of Baylor University • College of Arts & Sciences • 2001 with individual conscience, the hymn of the south, or the priesthood of the believer. Haunted, driving north, I watched the horizon gray over Oklahoma, the rim of fires drifting down from Manitoba. I stepped out hours later to the first cold of September, a season’s end. The magnolias were already old those last evenings, reflected in the watery light of summer rain. The air was dark with words. But this spring, a hymn heard through a distant window brought back the years before: The places where crepe myrtle blooms early and late, where old bells echo from a green Handel and Mendelssohn and all the music of Passover, where almost every lamppost has a name and shadows cross our days without erasing joy. Dr. Jane Hoogestraat (B.A., 1981) Poet and Associate Professor of English, Southwest Missouri State University College of Arts and Sciences PO Box 97344 Waco, TX 76798-7344 Change Service Requested A Letter from the Dean This issue of Collegium Studies sponsored a symposium on “Civil Society and the Search for focuses on the relationship Justice in Russia.” The symposium, held in February 2001, involved between professors and stu- research presentations from our faculty and students, as well as from dents. Every time I have heard prominent American and Russian scholars and journalists; the papers graduating seniors speak about currently are in press. -

Texas Review's Gordian Review

The Gordian Review Volume 2 2017 The Gordian Review Volume 2, 2017 Texas Review Press Huntsville, TX Copyright 2017 Texas Review Press, Sam Houston State University Department of English. ISSN 2474-6789. The Gordian Review volunteer staff: Editor in Chief: Julian Kindred Poetry Editor: Mike Hilbig Fiction Editor: Elizabeth Evans Nonfiction Editor: Timothy Bardin Cover Design: Julian Kindred All images were found, copyright-free, on Shutterstock.com. For those graduate students interesting in having their work published, please submit through The Gordian Review web- site (gordianreview.org) or via the Texas Review Press website (texasreviewpress.org). Only work by current or recently graduated graduate students (Masters or PhD level) will be considered for publication. If you have any questions, the staff can be contacted by email at [email protected]. Contents 15 “Nightsweats” Fiction by James Stewart III 1 “A Defiant Act” 16 “Counting Syllables” Poetry by Sherry Tippey Nonfiction by Cat Hubka 4 “Echocardiogram” 17 “Missed Connections” 5 “Ants Reappear Like Snowbirds” 6 “Bedtime Story” Poetry by Alex Wells Shapiro 6 “Simulacrum” 21 “Feralizing” 7 “Cat Nap” 21 “Plugging” 22 “Duratins” 23 “Opening” Nonfiction by Rebekah D. Jerabek 7 “Of Daughters” 23 “Desiccating” Poetry by Kirsten Shu-ying Chen Acknowledgements 14 “Astronimical dawn” 15 “Brainstem” Author Biographies A Defiant Act by James Stewart III father walks to the back of the family mini-van balancing four ice cream cones in his two hands. He’s holding them away from hisA body so they don’t drip onto his stained jeans in the midsummer heat. He somehow manages to open the back hatch of the van while balancing the treats. -

Pewdiepie, Popularity, and Profitability

Pepperdine Journal of Communication Research Volume 8 Article 4 2020 The 3 P's: Pewdiepie, Popularity, and Profitability Lea Medina Pepperdine University, [email protected] Eric Reed Pepperdine University, [email protected] Cameron Davis Pepperdine University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/pjcr Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Medina, Lea; Reed, Eric; and Davis, Cameron (2020) "The 3 P's: Pewdiepie, Popularity, and Profitability," Pepperdine Journal of Communication Research: Vol. 8 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/pjcr/vol8/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Journal of Communication Research by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 21 The 3 P’s: Pewdiepie, Popularity, & Popularity Lea Medina Written for COM 300: Media Research (Dr. Klive Oh) Introduction Channel is an online prole created on the Felix Arvid Ul Kjellberg—more website YouTube where users can upload their aectionately referred to as Pewdiepie—is original video content to the site. e factors statistically the most successful YouTuber, o his channel that will be explored are his with a net worth o over $15 million and over relationships with the viewers, his personality, 100 million subscribers. With a channel that relationship with his wife, and behavioral has uploaded over 4,000 videos, it becomes patterns. natural to uestion how one person can gain Horton and Wohl’s Parasocial such popularity and prot just by sitting in Interaction eory states that interacting front o a camera. -

February 26, 2013 - Uvm, Burlington, Vt Uvm.Edu/~Watertwr - Thewatertower.Tumblr.Com

volume 13 - issue 6 - tuesday, february 26, 2013 - uvm, burlington, vt uvm.edu/~watertwr - thewatertower.tumblr.com by benberrick UVM, we need to have a talk. I know things have been hard lately; with the transfer of presidential power, budget cuts, and communication breakdowns all over the place, it’s been nothing short of crazy out here. I understand that you need to relieve stress and chill out, but I just can’t condone the method that you have cho- sen. Just because everyone else is doing it, doesn’t make it okay, UVM, and no matter what kind of peer pressure is there, I expect better from you. So we need to talk about this. No, I’m not talking about all the mas- turbation—honestly, that’s healthy and in the future I’ll knock before I come in. We need to talk about the Harlem Shake. I know why you did it. Heck, there have been times when I’ve wanted to do it myself. Aft er exploding two weeks ago, the Harlem Shake went from something that only a few weirdo skateboarders did, to a by kerrymartin meme of epidemic proportions. Sure, the Keeping up with national politics, for as a tough contest between two intelli- Davis Center; it’s a point that seems obvi- fi rst couple times it was funny, clever even. all the work it takes, bears bitter fruit. I’m gent, qualifi ed, engaged, and open-minded ous, but is oft en overlooked. But within 48 hours, as with most memes, the kind of guy who attacks political apa- women. -

The 2Nd International Conference on Internet Pragmatics - Netpra2

THE 2ND INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON INTERNET PRAGMATICS - NETPRA2 INTERACTIONS, IDENTITIES, INTENTIONS 22–24 October 2020 BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Table of Contents Keynotes ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Anita Fetzer (University of Augsburg) ................................................................................................. 6 “It’s a very good thing to bring democracy erm directly to everybody at home”: Participation and discursive action in mediated political discourse ............................................................................ 6 Tuomo Hiippala (University of Helsinki) ............................................................................................ 7 Communicative situations on social media – a multimodal perspective ........................................ 7 Sirpa Leppänen (University of Jyväskylä) ........................................................................................... 8 Intentional identifications in digital interaction: how semiotization serves in fashioning selves and others ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Julien Longhi (University Cergy-Pontoise) ......................................................................................... 9 Building, exploring and analysing CMC corpora: a pragmatic tool-based approach to political discourse on the internet ................................................................................................................. -

You Ordered Your Crew to Attack Me!!!

1/31/2020 Machine Gun Kelly Sued for Bodyguards' Beatdown on Actor 'G-Rod' GOT A TIP? TMZ Live: Click Here to Watch! Kick O Super Bowl Weekend Dog The Bounty Hunter's Kids Get Ready For 'Taylor Swi: Jake Paul Destroys AnEsonGib With These Stars In Miami! Slam Proposal To Beth's Miss Americana' ... See Her In 1st Round KO, KSI Next?! | Friend Moon Through The Years! TMZ NEWSROOM Machine Gun Kelly Sued for Bodyguards' Beatdown on Actor 'G-Rod' MACHINE GUN KELLY Sued By Actor 'G-Rod' ... YOU ORDERED YOUR CREW TO ATTACK ME!!! 719 525 6/7/2019 3:04 PM PT https://www.tmz.com/2019/06/07/machine-gun-kelly-sued-bodyguards-battery-gabriel-rodriguez/ 1/8 1/31/2020 Machine Gun Kelly Sued for Bodyguards' Beatdown on Actor 'G-Rod' EXCLUSIVE Machine Gun Kelly's goons ganged up on a guy, and beat the hell outta him -- on video -- and now the victim's suing the rapper, claiming he ordered the attack. We broke the story ... Gabriel "G-Rod" Rodriguez confronted MGK back in September at an Atlanta restaurant and called him a "p***y" because he was pissed about Kelly's beef with Eminem. 9/15/18 0:00 / 1:02 BEATDOWN FOOTAGE ATL Police Department Later in the evening at a Hampton Inn, video footage shows G-Rod getting jumped and viciously body slammed, kicked and punched by a bunch of dudes allegedly in MGK's crew. At least 3 of the individuals were ID'd and charged with misdemeanor battery, but cops said MGK was in the clear because he wasn't a part of it. -

![Lhl]GH COURT of DELHI: NEW DELHI](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6878/lhl-gh-court-of-delhi-new-delhi-786878.webp)

Lhl]GH COURT of DELHI: NEW DELHI

lHl]GH COURT OF DELHI: NEW DELHI No.\) 2.../DHC/Gaz.lG-l/VLE.2(a)/2017 Dated, the 6/..st:- February, 2017. ORDER Hon'ble the Chief Justice and Judges of this COlu't have been pleased to make the following transfers/postings in the Delhi Higher Judicial Service with effect from 06.02.2017: S~ncofOfficcr T From I To District to Remarks No, I (MI'.! Ms.) I which allocated 0- 1 -I R.P.S. T~j; - PO, MACT-l, West, T~C ! ADJ-9, Central Vice Mr. Raj Kumar Central, THC 2 1Ramesh Kumar-! Special Judge (PC ASJ-5, North, North In a new cOllrt. Act)(CBI)-2, Saket Rohini 3 I Vinod Kuma: Special Judge (PC Act) Special Judge Central Vice Mr. Rajiv (CBI)-3, PHC (NDPS), Mehra appointed as Central, THC Principal Judge, Family Courts 4 Virender Kumar ADJ-I, East, KKD Special Judge (PC New Delhi Vice Mr. Vinod Goyal Act), (CBI)-03, Kumar PHC -----s Patamjit Singh ASJ-2, South-West, Special Judge (PC NOI'th Vice Mr. Sanjay Kr. Dwarka Act), West Aggarwal (CBI)-3, Rohini 6 Sukhvinder Kaur PO, MACT, North, ASJ-4, North Vice Mr. Vidya Rohini North, Rohini . Prakash T Salljay Kl'. Aggarwal Special Judge (PC Act), ASJ (Electricity), North- Vice Ms. Swaran (CBI)-03, Rohini North-West, Rohini West Kanta Sharma appointed as Principal Judge, Family Courts 8 Gulshan Kumar ASJ (Electricity), South ASJ-3, South-East Vice Mr. Sudesh West, Dwarka South-East, Saket Kumar-II 9 Dinesh Bhatt ASJ-4, Central, THC PO, MACT'-i; Central Vice Mr. -

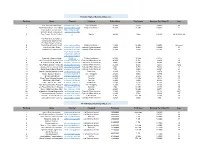

Sources & Data

YouTube Highest Earning Influencers Ranking Name Channel Category Subscribers Total views Earnings Per Video ($) Age 1 JoJo https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCeV2O_6QmFaaKBZHY3bJgsASiwa (Its JoJo Siwa) Life / Vlogging 10.6M 2.8Bn 569112 16 2 Anastasia Radzinskayahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJplp5SjeGSdVdwsfb9Q7lQ (Like Nastya Vlog) Children's channel 48.6M 26.9Bn 546549 6 Coby Cotton; Cory Cotton; https://www.youtube Garrett Hilbert; Cody Jones; .com/user/corycotto 3 Tyler Toney. (Dude Perfect) n Sports 49.4M 10Bn 186783 30,30,30,33,28 FunToys Collector Disney Toys ReviewToys Review ( FunToys Collector Disney 4 Toys ReviewToyshttps://www.youtube.com/user/DisneyCollectorBR Review) Children's channel 11.6M 14.9Bn 184506 Unknown 5 Jakehttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCcgVECVN4OKV6DH1jLkqmcA Paul (Jake Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 19.8M 6.4Bn 180090 23 6 Loganhttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCG8rbF3g2AMX70yOd8vqIZg Paul (Logan Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 20.5M 4.9Bn 171396 24 https://www.youtube .com/channel/UChG JGhZ9SOOHvBB0Y 7 Ryan Kaji (Ryan's World) 4DOO_w Children's channel 24.1M 36.7Bn 133377 8 8 Germán Alejandro Garmendiahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZJ7m7EnCNodqnu5SAtg8eQ Aranis (German Garmendia) Comedy / Entertainment 40.4M 4.2Bn 81489 29 9 Felix Kjellberg (PewDiePie)https://www.youtube.com/user/PewDiePieComedy / Entertainment 103M 24.7Bn 80178 30 10 Anthony Padilla and Ian Hecoxhttps://www.youtube.com/user/smosh (Smosh) Comedy / Entertainment 25.1M 9.3Bn 72243 32,32 11 Olajide William Olatunjihttps://www.youtube.com/user/KSIOlajidebt