The Improvised Violin Concerto - Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JS BACH (1685-1750): Violin and Oboe Concertos

BACH 703 - J. S. BACH (1685-1750) : Violin and Oboe Concertos Johann Sebastian Bach was born on March 21 st , l685, the son of Johann Ambrosius, Court Trumpeter for the Duke of Eisenach and Director of the Musicians of the town of Eisenach in Thuringia. For many years, members of the Bach family throughout Thuringia had held positions such as organists, town instrumentalists, or Cantors, and the family name enjoyed a wide reputation for musical talent. By the year 1703, 18-year-old Johann Sebastian had taken up his first professional position: that of Organist at the small town of Arnstadt. Then, in 1706 he heard that the Organist to the town of Mülhausen had died. He applied for the post and was accepted on very favorable terms. However, a religious controversy arose in Mülhausen between the Orthodox Lutherans, who were lovers of music, and the Pietists, who were strict puritans and distrusted art. So it was that Bach again looked around for more promising possibilities. The Duke of Weimar offered him a post among his Court chamber musicians, and on June 25, 1708, Bach sent in his letter of resignation to the authorities at Mülhausen. The Weimar years were a happy and creative time for Bach…. until in 1717 a feud broke out between the Duke of Weimar at the 'Wilhelmsburg' household and his nephew Ernst August at the 'Rote Schloss’. Added to this, the incumbent Capellmeister died, and Bach was passed over for the post in favor of the late Capellmeister's mediocre son. Bach was bitterly disappointed, for he had lately been doing most of the Capellmeister's work, and had confidently expected to be given the post. -

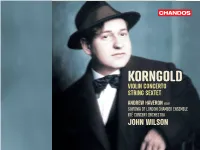

Korngold Violin Concerto String Sextet

KORNGOLD VIOLIN CONCERTO STRING SEXTET ANDREW HAVERON VIOLIN SINFONIA OF LONDON CHAMBER ENSEMBLE RTÉ CONCERT ORCHESTRA JOHN WILSON The Brendan G. Carroll Collection Erich Wolfgang Korngold, 1914, aged seventeen Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897 – 1957) Violin Concerto, Op. 35 (1937, revised 1945)* 24:48 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Dedicated to Alma Mahler-Werfel 1 I Moderato nobile – Poco più mosso – Meno – Meno mosso, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Poco meno – Tempo I – [Cadenza] – Pesante / Ritenuto – Poco più mosso – Tempo I – Meno, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Meno – Più mosso 9:00 2 II Romanze. Andante – Meno – Poco meno – Mosso – Poco meno (misterioso) – Avanti! – Tranquillo – Molto cantabile – Poco meno – Tranquillo (poco meno) – Più mosso – Adagio 8:29 3 III Finale. Allegro assai vivace – [ ] – Tempo I – [ ] – Tempo I – Poco meno (maestoso) – Fließend – Più tranquillo – Più mosso. Allegro – Più mosso – Poco meno 7:13 String Sextet, Op. 10 (1914 – 16)† 31:31 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Herrn Präsidenten Dr. Carl Ritter von Wiener gewidmet 3 4 I Tempo I. Moderato (mäßige ) – Tempo II (ruhig fließende – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III. Allegro – Tempo II – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Tempo II – Allmählich fließender – Tempo III – Wieder Tempo II – Tempo III – Drängend – Tempo I – Tempo III – Subito Tempo I (Doppelt so langsam) – Allmählich fließender werdend – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo I – Tempo II (fließend) – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III – Ruhigere (Tempo II) – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Sehr breit – Tempo II – Subito Tempo III 9:50 5 II Adagio. Langsam – Etwas bewegter – Steigernd – Steigernd – Wieder nachlassend – Drängend – Steigernd – Sehr langsam – Noch ruhiger – Langsam steigernd – Etwas bewegter – Langsam – Sehr breit 8:27 6 III Intermezzo. -

Danny Elfman's Violin Concerto

Danny Elfman’s Violin Concerto Friday, October 18 Today’s concert focuses not only on the renowned 10:30am concert music of Danny Elfman, but on a style of music that doesn’t tell a complete narrative. Rather, today’s selections paint a picture of a feeling, or an emotion, or a mysterious land- scape, by only using the power of music. Read on to find out more! Danny Elfman, American Composer (1953- ) Danny Elfman is an American composer most well known for his film music. He has composed music for film and TV such as The Simpsons, Men in Black, and Avengers: Age of Ultron. and has worked with pioneer- ing directors such as Tim Burton, Sam Raimi, Guillermo del Toro and Ang REPERTOIRE Lee. In 2004, Elfman began writing for the concert hall, such as Serenada Schizophrana (2005), Rabbit and Rogue (2008), and Eleven Eleven (2017). ELFMAN Concerto: “Eleven Eleven” Danny Elfman work- STRAUSS ing with longtime creative collaborator Death and and director, Tim Bur- Transfiguration, ton, on Alice in Wonderland (2010). Dance of the Seven Veils from Salome Concerto for Violin & Orchestra: “Eleven Eleven” composed in 2017, duration is 15 minutes This concerto, or larger-scale piece for an orchestra and a solo instrument, is approximately 40 minutes in duration and is divided into four movements. It features lyrical melodies inspired by early 20th century music, as well as more modern rhythms and har- monies. The title comes from the measure count, which hap- pens to be exactly 1,111 meas- ures long. The piece was written in collaboration with violinist Sandy Cameron. -

PROGRAM NOTES: “Violin Concerto”

PROGRAM NOTES: “Violin Concerto” I believe that one of the most rewarding aspects of life is exploring and discovering the magic and mysteries held within our universe. For a composer this thrill often takes place in the writing of a concerto…it is the exploration of an instrument’s world, a journey of the imagination, confronting and stretching an instrument’s limits, and discovering a particular performer’s gifts. The first movement of this concerto, written for the violinist, Hilary Hahn, carries a somewhat enigmatic title of “1726”. This number represents an important aspect of such a journey of discovery, for both the composer and the soloist. 1726 happens to be the street address of The Curtis Institute of Music, where I first met Hilary as a student in my 20th Century Music Class. An exceptional student, Hilary devoured the information in the class and was always open to exploring and discovering new musical languages and styles. As Curtis was also a primary training ground for me as a young composer, it seemed an appropriate tribute. To tie into this title, I make extensive use the intervals of unisons, 7ths, and 2nds, throughout this movement. The excitement of the first movement’s intensity certainly deserves the calm and pensive relaxation of the 2nd movement. This title, “Chaconni”, comes from the word “chaconne”. A chaconne is a chord progression that repeats throughout a section of music. In this particular case, there are several chaconnes, which create the stage for a dialog between the soloist and various members of the orchestra. The beauty of the violin’s tone and the artist’s gifts are on display here. -

June 29 to July 5.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES June 29 - July 5, 2020 PLAY DATE : Mon, 06/29/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto 6:11 AM Johann Nepomuk Hummel Serenade for Winds 6:31 AM Johan Helmich Roman Concerto for Violin and Strings 6:46 AM Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Symphony 7:02 AM Johann Georg Pisendel Concerto forViolin,Oboes,Horns & Strings 7:16 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Sonata No. 32 7:30 AM Jean-Marie Leclair Violin Concerto 7:48 AM Antonio Salieri La Veneziana (Chamber Symphony) 8:02 AM Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber Mensa sonora, Part III 8:12 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 34 8:36 AM Johannes Brahms Violin Sonata No. 3 9:05 AM Leroy Anderson Concerto for piano and orchestra 9:25 AM Arthur Foote Piano Quartet 9:54 AM Leroy Anderson Syncopated Clock 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem: Communio: Lux aeterna 10:06 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Violin Sonata No. 21, K 304/300c 10:23 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart DON GIOVANNI Selections 10:37 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Sonata for 2 pianos 10:59 AM Felix Mendelssohn String Quartet No. 3 11:36 AM Mauro Giuliani Guitar Concerto No. 1 12:00 PM Danny Elfman A Brass Thing 12:10 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Schwärmereien Concert Waltz 12:23 PM Franz Liszt Un Sospiro (A Sigh) 12:32 PM George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue 12:48 PM John Philip Sousa Our Flirtations 1:00 PM Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony No. 6 1:43 PM Michael Kurek Sonata for Viola and Harp 2:01 PM Paul Dukas La plainte, au loin, du faune...(The 2:07 PM Leos Janacek Sinfonietta 2:33 PM Johannes Brahms Violin Sonata No. -

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto Friday, January 12, 2018 at 11 am Jayce Ogren, Guest conductor Sibelius Symphony No. 7 in C Major Tchaikovsky Concerto for Violin and Orchestra Gabriel Lefkowitz, violin Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto For Tchaikovsky and The Composers Sibelius, these works were departures from their previ- ous compositions. Both Jean Sibelius were composed in later pe- (1865—1957) riods in these composers’ lives and both were pushing Johan Christian Julius (Jean) Sibelius their comfort levels. was born on December 8, 1865 in Hämeenlinna, Finland. His father (a doctor) died when Jean For Tchaikovsky, the was three. After his father’s death, the family Violin Concerto came on had to live with a variety of relatives and it was Jean’s aunt who taught him to read music and the heels of his “year of play the piano. In his teen years, Jean learned the hell” that included his disas- violin and was a quick study. He formed a trio trous marriage. It was also with his sister older Linda (piano) and his younger brother Christian (cello) and also start- the only concerto he would ed composing, primarily for family. When Jean write for the violin. was ready to attend university, most of his fami- Jean Sibelius ly (Christian stayed behind) moved to Helsinki For Sibelius, his final where Jean enrolled in law symphony became a chal- school but also took classes at the Helsinksi Music In- stitute. Sibelius quickly became known as a skilled vio- lenge to synthesize the tra- linist as well as composer. He then spent the next few ditional symphonic form years in Berlin and Vienna gaining more experience as a composer and upon his return to Helsinki in 1892, he with a tone poem. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

Houston Grand Opera Orchestra & Houston Ballet Orchestra

Houston Grand Opera Orchestra & Houston Ballet Orchestra 2019 Substitute and Extra Musicians Audition Material March 4th, 2019: Oboe & Bassoon March 6th, 2019: Horn, Trombone, Bass Trombone, Tuba, & Percussion March 7th, 2019: Violin, Viola, Cello, & Bass March 4th, 2019: Oboe & Bassoon Section Oboe Solo Repertoire Mozart, W. A. Oboe Concerto, Mvt. I, exposition Excerpts Brahms, J. Violin Concerto, Mvt. II, mm. 3–32 (Oboe 1) Strauss, R. Don Juan, beginning to four before B (Oboe 1) Strauss, R. Don Juan, four after L to seventeen after M (Oboe 1) Tchaikovsky, P. Casse-Noisette, Act I, No. 1, E to one before F (Oboe 2) Section Bassoon (optional Contrabassoon) Solo Repertoire Mozart, W. A. Bassoon Concerto, Mvt. I, exposition Excerpts Mozart, W. A. Le nozze di Figaro, Overture, mm. 1–58 Mozart, W. A. Le nozze di Figaro, Overture, mm. 139–171 Tchaikovsky, P. Casse-Noisette, Act I, No. 1, mm. 84–117 (Bassoon 1) Tchaikovsky, P. Casse-Noisette, Act II, No. 12b, mm. 33–End [skip long rests] (Bassoon 1) Wagner, R. Tannhäuser (Paris version), Overture, mm. 1–37 (Bassoon 2) Optional Contrabassoon Excerpt Strauss, R. Salome (full orchestration), six after 151 to four after 154 March 6th, 2019: Horn, Trombone, Bass Trombone, Tuba, & Percussion Section Horn Solo Repertoire Mozart, W. A. Concerto No. 2, Mvt. I, exposition or Mozart, W. A. Concerto No. 4, Mvt. I, exposition Excerpts Beethoven, L. Fidelio, Overture, mm. 5–16 (Horn 2 in E) Beethoven, L. Fidelio, Overture, mm. 45–55 (Horn 2 in E) Beethoven, L. Piano Concerto No. 5, mm. 14–107 (Horn 2 in E♭) Tchaikovsky, P. -

20 June 2021

20 June 2021 12:01 AM Claude Debussy (1862-1918), Maurice Ravel (orchestrator) Tarantelle styrienne Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra, Kazuhiro Koizumi (conductor) CACBC 12:07 AM Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) Keyboard Sonata in B flat major, Hob.16.41 Marc-Andre Hamelin (piano) PLPR 12:18 AM Grazyna Bacewicz (1909-1969) Suite for chamber orchestra (1946) Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Jan Krenz (conductor) PLPR 12:26 AM Giovanni Valentini (1582/3-1649) Fra bianchi giglie, a 7 La Capella Ducale, Musica Fiata Koln DEWDR 12:35 AM Armas Jarnefelt (1869-1968) Korsholma - Symphonic Poem Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Ulf Soderblom (conductor) FIYLE 12:52 AM Marin Marais (1656-1728) Caprice ou Sonate (from Pieces de Viole, 4e Livre, Paris 1717) Pierre Pitzl (viola da gamba), Marcy Jean Brenner (viola da gamba), Augusta Campagne (harpsichord) ATORF 12:58 AM John Ireland (1879-1962) A Downland Suite Hannaford Street Silver Band, Bramwell Tovey (conductor) CACBC 01:15 AM Charles Avison (1709-1770) Concerto Grosso No.2 in G major for strings and continuo Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra, Jeanne Lamon (director) CACBC 01:29 AM Johan Halvorsen (1864-1935) Symphony No 2 in D minor, Op 67 Norwegian Radio Orchestra, Thomas Sondergard (conductor) NONRK 02:01 AM Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) Concerto in D major for 3 trumpets and timpani, TWV.54:D4 Stefan Schultz (trumpet), Alexander Mayr (trumpet), Jorn Schulze (trumpet), NDR Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, Riccardo Minasi (conductor) DENDR 02:09 AM Giles Farnaby (c. 1563 - 1640), Elgar Howarth (arranger) Fancies, -

Concerts from the Library of Congress 2017-2018

Concerts OF FROM THE LIBRARY CONGRESS OPEN SOURCE PROGRAMMING ConcertsOF FROM THE FROM LIBRARY CONGRESSOPEN SOURCE PROGRAMMING Creativity can be messy. A glance at a handwritten manuscript, a trial-and-error filled attempt at song lyrics, or an early draft that bears little resemblance to the final work confirms it. Yet the fruits of the creative process gain clarity as we delve deeper. Our 2017-2018 season features performances of over fifty pieces drawing on handwritten sources, with the support of Primary countless other revealing documents from the Library’s sources special collections. Behind each performance are artists revealed! committed to sharing their insights and discoveries. TABLE OF CONTENTS Join us this season as we uncover new layers of PAGE 04 - FALL CONCERTS If you see a meaning, illuminating what lies beneath the surface. composition highlighted PAGE 20 - COUNTERPOINTS you’ll know that a PAGE 28 - SPRING CONCERTS primary source for that Concerts from the Library of Congress: piece is held in the PAGE 60- FRIENDS OF MUSIC Library’s collection. Go your open source for great music. PAGE 62 - TICKETING on the hunt for these national treasures and PAGE 63 - SEASON AT A GLANCE decode the music before special EVENT TICKETS AVAILABLE SEPTEMBER 6, 2017 the concert. fall 2017 EVENT TICKETS AVAILABLE SEPTEMBER 20, 2017 loc.gov spring 2018 EVENT TICKETS AVAILABLE DECEMBER 13, 2017 2 loc.gov/concerts 3 fall CONCERTS , holograph in ink, Library of Congress, Source: Johannes Brahms, Piano Trio no. 2 in C major, op.87 Gertrude Clarke Whittall Foundation Collection 4 5 WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 18 - 8PM WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 18 - 8PM EnsembleMUSIC OF STEVE REICH Signal Our season opens with an extraordinary evening of chamber works by a pioneering composer whose music has profoundly influenced composers and musicians worldwide. -

Programnotes Sheherezade B

PROGRAM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FIFTH SEASON Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Wednesday, March 30, 2016, at 6:30 Afterwork Masterworks Susanna Mälkki Conductor Gil Shaham Violin Bartók Violin Concerto No. 2 Allegro non troppo Theme and Variations: Andante tranquillo Rondo: Allegro molto GIL SHAHAM Rimsky-Korsakov Sheherazade, Op. 35 The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship The Tale of the Dervish Prince The Young Prince and the Young Princess Festival in Baghdad, and the Sea Robert Chen, violin There will be no intermission. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is grateful to WBBM Newsradio 780 and 105.9 FM for its generous support of the Afterwork Masterworks series. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. PROGRAM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FIFTH SEASON Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, March 31, 2016, at 8:00 Friday, April 1, 2016, at 1:30 Saturday, April 2, 2016, at 8:00 Susanna Mälkki Conductor Gil Shaham Violin Debussy Gigues, Images for Orchestra No. 1 Bartók Violin Concerto No. 2 Allegro non troppo Theme and Variations: Andante tranquillo Rondo: Allegro molto GIL SHAHAM INTERMISSION Rimsky-Korsakov Sheherazade, Op. 35 The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship The Tale of the Dervish Prince The Young Prince and the Young Princess Festival in Baghdad, and the Sea Robert Chen, violin Thursday’s performance has been made possible by a generous gift from Robert J. -

Concertos for Oboe and Oboe D'amore

J.S. Bach Concertos for Oboe and Oboe d’amore Gonzalo X. Ruiz Portland Baroque Orchestra Monica Huggett J.S. Bach (1685-1750) Concertos for Oboe and Oboe d’amore Gonzalo X. Ruiz, baroque oboes Portland Baroque Orchestra Concerto for oboe in G minor, BWV 1056R Concerto for oboe d’amore in A major, BWV 1055R Reconstruction of BWV 1056, Concerto in F minor for Harpsichord Reconstruction of BWV 1055, Concerto in A major for Harpsichord 1 I. [Moderato] 3:10 10 I. [Allegro] 3:56 2 II. Largo 2:25 11 II. Larghetto 4:39 3 III. Presto 3:13 12 III. Allegro ma non tanto 4:08 Concerto for oboe in F major, BWV 1053R Concerto for violin and oboe in C minor, BWV 1060R Reconstruction of BWV 1053, Concerto in E major for Harpsichord Reconstruction of BWV 1060, Concerto in C minor for Two Harpsichords 4 I. [Allegro] 7:05 Monica Huggett, violin soloist 5 II. Siciliano 4:56 13 I. Allegro 4:30 6 III. Allegro 5:46 14 II. Adagio 4:30 15 III. Allegro 3:27 Concerto for oboe in D minor, BWV 1059R Reconstruction based on a concerto fragment and Cantatas 35 and 156 16 Aria from Cantata 51: “Höchster, mache deine Güte” 4:56 7 I. Allegro 5:12 Transcribed by Gonzalo X. Ruiz 8 II. Adagio 2:26 9 III. Presto 3:02 Total Time 67:21 Performed on Period Instruments 2 Gonzalo X. Ruiz, baroque oboes Born in La Plata, Argentina, Gonzalo X. Ruiz is one of the world’s most critically acclaimed baroque oboists.