Natipnal Register of Historic Places DEC 141988 Multiple Property

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tonto National Forest Travel Management Plan

Comments on the DEIS for the Tonto National Forest Travel Management Plan Submitted September 15, 2014 via Electronic Mail and Certified Mail #7014-0150-0001-2587-0812 On Behalf of: Archaeology Southwest Center for Biological Diversity Sierra Club The Wilderness Society WildEarth Guardians Table of Contents II. Federal Regulation of Travel Management .................................................................................. 4 III. Impacts from Year Round Motorized Use Must be Analyzed .................................................. 5 IV. The Forest Service’s Preferred Alternative .............................................................................. 6 V. Desired Conditions for Travel Management ................................................................................. 6 VI. Purpose and Need Statements ................................................................................................... 7 VII. Baseline Determination .............................................................................................................. 8 A. The Forest Service cannot arbitrarily reclassify roads as “open to motor vehicle use” in the baseline. ............................................................................................................................................ 10 B. Classification of all closed or decommissioned routes as “open to motor vehicle use” leads to mischaracterization of the impacts of the considered alternatives. ...................................................... 11 C. Failure -

CEMOZOIC DEPOSITS in the SOUTHERN FOOTHILLS of the SANTA CATALINA MOUNTAINS NEAR TUCSON, ARIZONA Ty Klaus Voelger a Thesis Submi

Cenozoic deposits in the southern foothills of the Santa Catalina Mountains near Tucson, Arizona Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Voelger, Klaus, 1926- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 10:53:10 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/551218 CEMOZOIC DEPOSITS IN THE SOUTHERN FOOTHILLS OF THE SANTA CATALINA MOUNTAINS NEAR TUCSON, ARIZONA ty Klaus Voelger A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of Geology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in the Graduate College, University of Arizona 1953 Approved; , / 9S~J Director of Thesis ^5ate Univ. of Arizona Library The research on which this thesis is based was com pleted by Mr. Klaus Voelger of Berlin, Germany, while he was studying at the University of Arizona under the program of the Institute of International Education. The final draft was written after Mr. Voelgerf s return to his home in the Russian-occupied zone of Berlin. Difficulties such as a shortage of typing paper of uniform grade and the impossibility of adequate supervision and advice on matters of terminology, punctuation, and English usage account for certain details in which this thesis may depart from stand ards of the Graduate College of the University of Arizona. These details are largely mechanical, and it is felt that they do not detract appreciably from the quality of the research nor the clarity of presentation of the results. -

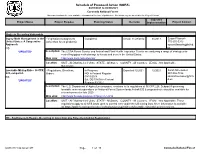

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Coronado National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Coronado National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Gypsy Moth Management in the - Vegetation management Completed Actual: 11/28/2012 01/2013 Susan Ellsworth United States: A Cooperative (other than forest products) 775-355-5313 Approach [email protected]. EIS us *UPDATED* Description: The USDA Forest Service and Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service are analyzing a range of strategies for controlling gypsy moth damage to forests and trees in the United States. Web Link: http://www.na.fs.fed.us/wv/eis/ Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Nationwide. Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Sarah Shoemaker 228, subpart A. Orders NOI in Federal Register 907-586-7886 EIS 09/13/2018 [email protected] d.us *UPDATED* Est. DEIS NOA in Federal Register 03/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. -

2006 Tumamoc Hill Management Plan

TUMAMOC HILL CUL T URAL RESOURCES POLICY AND MANAGEMEN T PLAN September 2008 This project was financed in part by a grant from the Historic Preservation Heritage Fund which is funded by the Arizona Lottery and administered by the Arizona State Parks Board UNIVERSI T Y OF ARIZONA TUMAMOC HILL CUL T URAL RESOURCES POLICY AND MANAGEMEN T PLAN Project Team Project University of Arizona Campus & Facilities Planning David Duffy, AICP, Director, retired Ed Galda, AICP, Campus Planner John T. Fey, Associate Director Susan Bartlett, retired Arizona State Museum John Madsen, Associate Curator of Archaeology Nancy Pearson, Research Specialist Nancy Odegaard, Chair, Historic Preservation Committee Paul Fish, Curator of Archaeology Suzanne Fish, Curator of Archaeology Todd Pitezel, Archaeologist College of Architecture and Landscape Architecture Brooks Jeffery, Associate Dean and Coordinator of Preservation Studies Tumamoc Hill Lynda C. Klasky, College of Science U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service Western Archaeological and Conservation Center Jeffery Burton, Archaeologist Consultant Team Cultural Affairs Office, Tohono O’odham Nation Peter Steere Joseph Joaquin September 2008 UNIVERSI T Y OF ARIZONA TUMAMOC HILL CUL T URAL RESOURCES POLICY AND MANAGEMEN T PLAN Cultural Resources Department, Gila River Indian Community Barnaby V. Lewis Pima County Cultural Resources and Historic Preservation Office Linda Mayro Project Team Project Loy C. Neff Tumamoc Hill Advisory Group, 1982 Gayle Hartmann Contributing Authors Jeffery Burton John Madsen Nancy Pearson R. Emerson Howell Henry Wallace Paul R. Fish Suzanne K. Fish Mathew Pailes Jan Bowers Julio Betancourt September 2008 UNIVERSI T Y OF ARIZONA TUMAMOC HILL CUL T URAL RESOURCES POLICY AND MANAGEMEN T PLAN This project was financed in part by a grant from the Historic Preservation Heritage Fund, which is funded by the Arizona Lottery and administered by the Arizona State Acknowledgments Parks Board. -

2010 General Management Plan

Montezuma Castle National Monument National Park Service Mo n t e z u M a Ca s t l e na t i o n a l Mo n u M e n t • tu z i g o o t na t i o n a l Mo n u M e n t Tuzigoot National Monument U.S. Department of the Interior ge n e r a l Ma n a g e M e n t Pl a n /en v i r o n M e n t a l as s e s s M e n t Arizona M o n t e z u MONTEZU M A CASTLE MONTEZU M A WELL TUZIGOOT M g a e n e r a l C a s t l e M n a n a g e a t i o n a l M e n t M P o n u l a n M / e n t e n v i r o n • t u z i g o o t M e n t a l n a a t i o n a l s s e s s M e n t M o n u M e n t na t i o n a l Pa r k se r v i C e • u.s. De P a r t M e n t o f t h e in t e r i o r GENERAL MANA G E M ENT PLAN /ENVIRON M ENTAL ASSESS M ENT General Management Plan / Environmental Assessment MONTEZUMA CASTLE NATIONAL MONUMENT AND TUZIGOOT NATIONAL MONUMENT Yavapai County, Arizona January 2010 As the responsible agency, the National Park Service prepared this general management plan to establish the direction of management of Montezuma Castle National Monument and Tu- zigoot National Monument for the next 15 to 20 years. -

Socioeconomic Assessment for the Tonto National Forest

4. Access and Travel Patterns This section examines historic and current factors affecting access patterns and transportation infrastructure within the four counties surrounding Tonto National Forest (TNF). The information gathered is intended to outline current and future trends in forest access as well as potential barriers to access encountered by various user groups. Primary sources of data on access and travel patterns for the state’s national forests include the Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT), the Arizona Department of Commerce (ADOC), and the circulation elements of individual county comprehensive plans. Indicators used to assess access and travel patterns include existing road networks and planned improvements, trends in vehicle miles traveled (VMT) on major roadways, seasonal traffic flows, and county transportation planning priorities. Additional input on internal access issues has been sought directly from forest planning staff. Various sources of information for the area surrounding TNF cite the difficulty of transportation planning in the region given its vast geographic scale, population growth, pace of development, and constrained transportation funding. In an effort to respond effectively to such challenges, local and regional planning authorities stress the importance of linking transportation planning with preferred land uses. Data show that the area surrounding Tonto National Forest saw relatively large increases in VMT between 1990 and 2000, mirroring the region’s relatively strong population growth over the same period. Information gathered from the Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT) and county comprehensive plans suggest that considerable improvements are currently scheduled for the region’s transportation network, particularly when compared to areas surrounding Arizona’s other national forests. -

Utah Historical Quarterly, Use of the Atomic Bomb

78 102 128 NO. 2 NO. I VOL. 86 VOL. I 148 179 UHQ 75 CONTENTS Departments 78 The Crimson Cowboys: 148 Remembering Topaz and Wendover The Remarkable Odyssey of the 1931 By Christian Heimburger, Jane Beckwith, Claflin-Emerson Expedition Donald K. Tamaki, and Edwin P. Hawkins, Jr. By Jerry D. Spangler and James M. Aton 165 Voices from Drug Court By Randy Williams 102 Small but Significant: The School of Nursing at Provo 77 In This Issue General Hospital, 1904–1924 By Polly Aird 172 Book Reviews & Notices 128 The Mountain Men, the 179 In Memoriam Cartographers, and the Lakes 182 Contributors By Sheri Wysong 183 Utah In Focus Book Reviews 172 Depredation and Deceit: The Making of the Jicarilla and Ute Wars in New Mexico By Gregory F. Michno Reviewed by Jennifer Macias 173 Juan Rivera’s Colorado, 1765: The First Spaniards among the Ute and Paiute Indians on the Trail to Teguayo By Steven G. Baker, Rick Hendricks, and Gail Carroll Sargent Reviewed by Robert McPherson 175 Isabel T. Kelly’s Southern Paiute Ethnographic Field Notes, 1932–1934, Las Vegas NO. 2 NO. Edited by Catherine S. Fowler and Darla Garey-Sage I Reviewed by Heidi Roberts 176 Mountain Meadows Massacre: Collected Legal Papers Edited by Richard E. Turley, Jr., Janiece L. Johnson, VOL. 86 VOL. and LaJean Purcell Carruth I Reviewed by Gene A. Sessions. UHQ Book Notices 177 Cowboying in Canyon Country: 76 The Life and Rhymes of Fin Bayles, Cowboy Poet By Robert S. McPherson and Fin Bayles 178 Dime Novel Mormons Edited by Michael Austin and Ardis E. -

The Use of Building Technology in Cultural Forensics: a Pre-Columbian Case Study

92 ARCHITECTURE: MATERIAL AND IMAGINED The Use of Building Technology in Cultural Forensics: A Pre-Columbian Case Study M. IVER WAHL, AIA University of Oklahoma INTRODUCTION Corners" area ofthe American Southwest is perhaps the most unique building form of the Anasazi culture, but it does not This paper poses the possibility that as early as 750 AD, seem to exist in Mesoamerica. In the world of architecture, technology transfer may have taken place between Pre- this argues significantly against significant Mesoamerican/ Columbian Peru and the Anasazi culture in UtaWColorado. Anasazi ''diffusion" theories. The possibility of such a cultural link became apparent to The prevailing theory for the "in-situ" evolution of the this researcher in 1976 while executing graduate field work kiva building type was proposed by John Otis Brew in 1946. in Central America; however, further study has awaited Brew dismissed outside cultural diffusion as necessary to adequate funding. If such transfer existed, the probable route kiva development based on his field studies at Alkali Ridge, would seem to have been from Peru north along the Pacific Utah. Briefly his theory traces the shift from the Basket I11 coast, then up the Colorado River to the San Juan area of pit house (used as a domestic residence), to the ceremonial UtaWColorado. kiva configuration common to Pueblo I1 period of the Anasazi culture. His study of this subject is thorough, and PURPOSE continues to largely accepted by archaeologists. However, The first objective of this study has been to determine if this this well-developed theory did not specifically address the tentative hypothesis is sufficiently plausible to warrant unique "corbeled-dome" or "cribbed roof structure used at further testing. -

Federal Register/Vol. 63, No. 242/Thursday, December 17, 1998

Federal Register / Vol. 63, No. 242 / Thursday, December 17, 1998 / Notices 69651 representatives of the Camp Verde remains at the time of death or later as professional staff in consultation with Yavapai-Apache Indian Community, the part of the death rite or ceremony. representatives of the Jamestown Havasupai Tribe, the Hopi Tribe, the Lastly, officials of the USDA Forest S'Klallam Tribe. Hualapai Tribe, the Navajo Nation, the Service have also determined that, During 1975- November 16, 1990, Pueblo of Zuni, and the Yavapai- pursuant to 43 CFR 10.2 (e), there is a human remains representing six Prescott Indian Tribe. relationship of shared group identity individuals were recovered from the Between 1965-1975, human remains which can be reasonably traced between Walan Point and Bugge Spit sites at Port representing 21 individuals were these Native American human remains Hadlock Detachment located on Indian recovered from four sites (AZ and associated funerary objects, the Island near Port Hadlock, WA during N:04:0002; AZ N:04:0005; AZ Hopi Tribe, and the Yavapai-Prescott archeological surveys and construction N:04:0012; and AZ N:04:0017) within Indian Tribe. projects by U.S. Navy personnel. No the Prescott National Forest during This notice has been sent to officials known individuals were identified. The legally authorized excavations of the Camp Verde Yavapai-Apache 42 associated funerary objects include conducted by Arizona State University. Indian Community, the Havasupai an antler tine, worked bone, an antler No known individuals were identified. Tribe, the Hopi Tribe, the Hualapai wedge, bone blanket pin, pendant, shell The 23 associated funerary objects Tribe, the Navajo Nation, the Pueblo of bead, dentalium, holed pectin shell, include ceramic fragments; bone and Zuni, and the Yavapai-Prescott Indian olivella shel bead, glass trade beads, and stone tools; burned animal bones; Tribe. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for the USA (W7A

Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7A - Arizona) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S53.1 Issue number 5.0 Date of issue 31-October 2020 Participation start date 01-Aug 2010 Authorized Date: 31-October 2020 Association Manager Pete Scola, WA7JTM Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Document S53.1 Page 1 of 15 Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGE CONTROL....................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Program Derivation ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 General Information ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Final Ascent -

Noel Morss, 1904-1981

344 AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 47, No. 2,1982] NOEL MORSS, 1904-1981 Noel Morss died on April 24, 1981, at the age of 77. An attorney, he was a practitioner of that uniquely Bostonian profession of "Trustee," which means he managed his own and other peo ple's money in effective and profitable ways. Because of the skill of these "trustees," Boston- ians, and New Englanders in general, have been able to accomplish so much during the last hun dred years or so. To archaeologists, however, he is the scholar who defined the Fremont Culture of eastern Utah. He began archaeological fieldwork in the mid-1920s in northern Arizona, on the Kaibito and Rainbow plateaus and in the Chinle Valley, under the inspiration of Samuel J. Guernsey and A. V. Kidder. While most of the young students of that time devoted themselves to the traditional "Southwest" of the San Juan River drainage and south ward into northern Arizona and New Mexico, Morss's curiosity led him northward into the can yons of the Colorado, Green, and Grand rivers and the mesas overlooking them. He was more and more impressed by the progressive variations on the Pueblo theme that were found as one moved northward in Utah and the continued underlying presence of the Basketmaker Culture. Barrier Canyon, the Fremont River, the Kaiparowitz Plateau, and, in northeastern Utah, Hill and Willow creeks on the East Tavaputs and the western tributaries of the Green; Range Creek, Nine Mile Can yon, and Minnie Maude—all these provided him with the materials from which the Fremont Culture was woven. -

Free PDF Download

ARCHAEOLOGY SOUTHWEST CONTINUE ON TO THE NEXT PAGE FOR YOUR magazineFREE PDF (formerly the Center for Desert Archaeology) is a private 501 (c) (3) nonprofit organization that explores and protects the places of our past across the American Southwest and Mexican Northwest. We have developed an integrated, conservation- based approach known as Preservation Archaeology. Although Preservation Archaeology begins with the active protection of archaeological sites, it doesn’t end there. We utilize holistic, low-impact investigation methods in order to pursue big-picture questions about what life was like long ago. As a part of our mission to help foster advocacy and appreciation for the special places of our past, we share our discoveries with the public. This free back issue of Archaeology Southwest Magazine is one of many ways we connect people with the Southwest’s rich past. Enjoy! Not yet a member? Join today! Membership to Archaeology Southwest includes: » A Subscription to our esteemed, quarterly Archaeology Southwest Magazine » Updates from This Month at Archaeology Southwest, our monthly e-newsletter » 25% off purchases of in-print, in-stock publications through our bookstore » Discounted registration fees for Hands-On Archaeology classes and workshops » Free pdf downloads of Archaeology Southwest Magazine, including our current and most recent issues » Access to our on-site research library » Invitations to our annual members’ meeting, as well as other special events and lectures Join us at archaeologysouthwest.org/how-to-help In the meantime, stay informed at our regularly updated Facebook page! 300 N Ash Alley, Tucson AZ, 85701 • (520) 882-6946 • [email protected] • www.archaeologysouthwest.org ARCHAEOLOGY SOUTHWEST SPRING 2014 A QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF ARCHAEOLOGYmagazine SOUTHWEST VOLUME 28 | NUMBER 2 A Good Place to Live for more than 12,000 Years Archaeology in Arizona's Verde Valley 3 A Good Place to Live for More Than 12,000 Years: Archaeology ISSUE EDITOR: in Arizona’s Verde Valley, Todd W.