2006 Tumamoc Hill Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CEMOZOIC DEPOSITS in the SOUTHERN FOOTHILLS of the SANTA CATALINA MOUNTAINS NEAR TUCSON, ARIZONA Ty Klaus Voelger a Thesis Submi

Cenozoic deposits in the southern foothills of the Santa Catalina Mountains near Tucson, Arizona Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Voelger, Klaus, 1926- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 10:53:10 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/551218 CEMOZOIC DEPOSITS IN THE SOUTHERN FOOTHILLS OF THE SANTA CATALINA MOUNTAINS NEAR TUCSON, ARIZONA ty Klaus Voelger A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of Geology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in the Graduate College, University of Arizona 1953 Approved; , / 9S~J Director of Thesis ^5ate Univ. of Arizona Library The research on which this thesis is based was com pleted by Mr. Klaus Voelger of Berlin, Germany, while he was studying at the University of Arizona under the program of the Institute of International Education. The final draft was written after Mr. Voelgerf s return to his home in the Russian-occupied zone of Berlin. Difficulties such as a shortage of typing paper of uniform grade and the impossibility of adequate supervision and advice on matters of terminology, punctuation, and English usage account for certain details in which this thesis may depart from stand ards of the Graduate College of the University of Arizona. These details are largely mechanical, and it is felt that they do not detract appreciably from the quality of the research nor the clarity of presentation of the results. -

Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Southwestern Region, 2008

United States Department of Forest Insect and Agriculture Forest Disease Conditions in Service Southwestern the Southwestern Region Forestry and Forest Health Region, 2008 July 2009 PR-R3-16-5 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720- 2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Cover photo: Pandora moth caterpillar collected on the North Kaibab Ranger District, Kaibab National Forest. Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Southwestern Region, 2008 Southwestern Region Forestry and Forest Health Regional Office Salomon Ramirez, Director Allen White, Pesticide Specialist Forest Health Zones Offices Arizona Zone John Anhold, Zone Leader Mary Lou Fairweather, Pathologist Roberta Fitzgibbon, Entomologist Joel McMillin, Entomologist -

Arizona Relocation Guide

ARIZONA RELOCATION GUIDE WELCOME TO THE VALLEY OF THE SUN Landmark Title is proud to present the greatest selection of golf courses. As the following relocation guide! If you are cultural hub of the Southwest, Phoenix is thinking of moving to the Valley of the also a leader in the business world. Sun, the following will help you kick The cost of living compared with high start your move to the wonderful quality of life is favorable com- greater Phoenix area. pared to other national cities. FUN FACT: Arizona is a popular destination and is We hope you experience and growing every year. There are plenty of enjoy everything this state that Arizona’s flag features a copper-colored activities to partake in, which is easy to we call home, has to offer. star, acknowledging the state’s leading do with 300+ days of sunshine! role in cooper when it produced 60% of the total for the United States. There is something for everyone; the outdoor enthusiast, recreational activities, hospitality, dining and shopping, not to mention the nation’s 3 HISTORY OF THE VALLEY Once known as the Arizona Territory, built homes in, what was known as, By the time the United States entered WW the Valley of the Sun contained one Pumkinville where Swilling had planted II, one of the 7 natural wonders of the of the main routes to the gold fields in the gourds along the canal banks. Duppa world, the Grand Canyon, had become California. Although gold and silver were presented the name of Phoenix as related a national park, Route 66 was competed discovered in some Arizona rivers and to the story of the rebirth of the mythical and Pluto had been discovered at the mountains during the 1860’s, copper bird born from the ashes. -

2010 General Management Plan

Montezuma Castle National Monument National Park Service Mo n t e z u M a Ca s t l e na t i o n a l Mo n u M e n t • tu z i g o o t na t i o n a l Mo n u M e n t Tuzigoot National Monument U.S. Department of the Interior ge n e r a l Ma n a g e M e n t Pl a n /en v i r o n M e n t a l as s e s s M e n t Arizona M o n t e z u MONTEZU M A CASTLE MONTEZU M A WELL TUZIGOOT M g a e n e r a l C a s t l e M n a n a g e a t i o n a l M e n t M P o n u l a n M / e n t e n v i r o n • t u z i g o o t M e n t a l n a a t i o n a l s s e s s M e n t M o n u M e n t na t i o n a l Pa r k se r v i C e • u.s. De P a r t M e n t o f t h e in t e r i o r GENERAL MANA G E M ENT PLAN /ENVIRON M ENTAL ASSESS M ENT General Management Plan / Environmental Assessment MONTEZUMA CASTLE NATIONAL MONUMENT AND TUZIGOOT NATIONAL MONUMENT Yavapai County, Arizona January 2010 As the responsible agency, the National Park Service prepared this general management plan to establish the direction of management of Montezuma Castle National Monument and Tu- zigoot National Monument for the next 15 to 20 years. -

Visibility at Saguaro National Park NPS/A

National Park Service Sonoran Desert Network U.S. Department of the Interior Air Quality Monitoring Brief Intermountain Region Inventory & Monitoring Program 2010 Visibility at Saguaro National Park NPS/A. WONDRAK BIEL Importance Both the Clean Air Act and the National Park Service (NPS) Organic Act protect air resources in national parks. Saguaro National Park is designated as a Class I area, receiving the highest protection under the Clean Air Act. Understanding changes in air quality can aid in interpreting changes in oth- er monitored vital signs and support evaluation of compli- ance with legislative and reporting requirements. At Sagua- ro NP, the Sonoran Desert Network has identifi ed ozone and visibility as high-priority vital signs for monitoring. Long-term Monitoring For Saguaro National Park, the Sonoran Desert Network (SODN) acquires, analyzes, and reports on air quality data from the web-based program archives of the National Park Airshed, Saguaro National Park. Service–Air Resources Division (NPS-ARD) Gaseous Pollut- ant Monitoring Program (ozone) and the Interagency Moni- are those resources that are potentially sensitive to air pollu- toring of Protected Visual Environments (IMPROVE) Pro- tion, and include vegetation, wildlife, water quality, soils, and gram (visibility). visibility. At present, visibility has been identifi ed as the most sensitive AQRV in the park; other AQRVs may also be sensi- Because the NPS-ARD has determined that particulate (vis- tive, but have not been suffi ciently studied. Although visibility ibility) monitors within 100 km (60 miles) may be reasonably in the park is still superior to that in many parts of the country, considered representative of a park’s air quality, the IMPROVE it is often impaired by light-scattering pollutants (haze). -

Guide to Parks & Facilities Swimming Pools

Marana & Oro Valley GUIDE TO PARKS & FACILITIES SWIMMING POOLS HIKING & TRAILS 1 San Lucas Community Park 16 Honey Bee Canyon Park Marana’s community pool is located at Ora Mae Harn District Park, 13251 OUTDOOR 14040 N. Adonis Rd. 13880 N. Rancho Vistoso Blvd. N. Lon Adams Road. It has long been a favorite way for area residents and Ramadas, ball fields, dog park, volleyball court, Hiking trails, ramadas, restrooms visitors to cool down during the hot summer months. In operation May playground, basketball court, restrooms, shared through September, the pool is open for any and all seeking a great way use path, fitness stations 17 Big Wash Linear Park to relax near the water in a beautiful park setting. A splash pad at Marana Accessible from Oro Valley Marketplace (Tangerine Recreation Heritage River Park, 12205 N. Tangerine Farms Road, features an agrarian WILD BURRO TRAIL Ora Mae Harn District Park 2 Rd. & Oracle Rd.) and from Steam Pump Village theme water features. There is also a splash pad at Crossroads at Silverbell 13250 N. Lon Adams Rd. (Oracle Rd., north of First Ave.) MARANA HERITAGE RIVER PARK brochure & map District Park, 7548 N. Silverbell Road. Hit the trails in Marana with year-round hiking. For stunning views of mountains, plants and wildlife, visit the Ball fields, ramadas, grills, tennis courts, Shared use path, great for walking, running and cycling vast trail network in the Tortolita Mountains, home to the Dove Mountain community and its Ritz-Carlton resort. pickleball courts, basketball courts, swimming The Oro Valley Aquatic Center is located within James D. -

A History of Saguaro Cactus Monitoring in Saguaro National Park, 1939–2007

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center A History of Saguaro Cactus Monitoring in Saguaro National Park, 1939–2007 Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR—2009/093 ON THE COVERS Front: Saguaro cacti, Tucson Mountain District, Saguaro National Park. NPS/E. Ahnmark. Inside Back: Saguaro cacti, Saguaro National Park. NPS photo. A History of Saguaro Cactus Monitoring in Saguaro National Park, 1939–2007 Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR—2009/093 Authors Eric B. Ahnmark Don E. Swann Saguaro National Park 3693 South Old Spanish Trail Tucson, Arizona 85730-5601 Editing and Design Alice Wondrak Biel Sonoran Desert Network 7660 E. Broadway Blvd., Suite 303 Tucson, Arizona 85710 February 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado ii National Park Service The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to oth- ers in the management of natural resources, including the scientifi c community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifi cally credible, technically accu- rate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. Natural Resource Reports are the designated medium for disseminating high priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. Examples of the diverse array of reports published in this series include vital signs monitoring plans; “how to” resource management papers; proceedings of resource management workshops or conferences; annual reports of resource programs or divisions of the Natural Resource Program Center; resource action plans; fact sheets; and regularly-published newsletters. -

Dark Sky Sanctuaries in Arizona

Dark Sky Sanctuaries in Arizona Eric Menasco NPS Terry Reiners Arizona is the astrotourism capital of the United States. Its diverse landscape—from the Grand Canyon and ponderosa forests in the north to the Sonoran Desert and “sky islands” in the south—is home to more certified Dark Sky Places than any other U.S. state. In fact, no country outside the U.S. can rival Arizona’s 16 dark-sky communities and parks. Arizona helped birth the dark-sky preservation movement when, in 2001, the International Dark Sky Association (IDA) designated Flagstaff as the world’s very first Dark Sky Place for the city’s commitment to protecting its stargazing- friendly night skies. Since then, six other Arizona communities—Sedona, Big Park, Camp Verde, Thunder Mountain Pootseev Nightsky and Fountain Hills—have earned Dark Sky status from the IDA. Arizona also boasts nine Dark Sky Parks, defined by the IDA as lands with “exceptional quality of starry nights and a nocturnal environment that is specifically protected for its scientific, natural, educational, cultural heritage, and/or public enjoyment.” The most famous of these is Grand Canyon National Park, where remarkably beautiful night skies lend draw-dropping credence to the Park Service’s reminder that “half the park is after dark Of the 16 Certified IDA International Dark Sky Communities in the US, 6 are in Arizona. These include: • Big Park/Village of Oak Creek, Arizona • Camp Verde, Arizona • Flagstaff, Arizona • Fountain Hills, Arizona • Sedona, Arizona • Thunder Mountain Pootsee Nightsky- Kaibab Paiute Reservation, Arizona Arizona Office of Tourism—Dark Skies Page 1 Facebook: @arizonatravel Instagram: @visit_arizona Twitter: @ArizonaTourism #VisitArizona Arizona is also home to 10 Certified IDA Dark Sky Parks, including: Northern Arizona: Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument Offering multiple hiking trails around this former volcanic cinder cone, visitors can join rangers on tours to learn about geology, wildlife, and lava flows. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for the USA (W7A

Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7A - Arizona) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S53.1 Issue number 5.0 Date of issue 31-October 2020 Participation start date 01-Aug 2010 Authorized Date: 31-October 2020 Association Manager Pete Scola, WA7JTM Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Document S53.1 Page 1 of 15 Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGE CONTROL....................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Program Derivation ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 General Information ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Final Ascent -

Tumamoc Hill 2

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK, Theme XX: Arts and Science, Science and Invention NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) 0MB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory—Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ali entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Desert Laboratory of the Carnegie Institution and or common Tumamoc Hill 2. Location street & number Intersection of W. Anklam Road and W. St. Mary's Road not for publication city, town Tucson vicinity of state Arizona code 04 county code 019 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district xx public xx occupied agriculture museum yx building(s) private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress xx educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious Object in process xx yes: restricted government xx scientific being considered _ yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military __ other: 4. Owner of Property name University of Arizona and Arizona State Lands Department (owns 340 acres) (owns 520 acres, leased to Univ. of AZ) street & number 1624 West Adams city, town Tucson, AZ 85721 vicinity of Phoenix state AZ 85007 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Pima County Courthouse street & number city, town Tucson state Arizona 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Historic American Buildings Surve^as tnis property been determined eligible? ——yes no date 1981 __ __________________—X- federal __ state __ county _ local depository for survey records Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. -

Floristic Surveys of Saguaro National Park Protected Natural Areas

Floristic Surveys of Saguaro National Park Protected Natural Areas William L. Halvorson and Brooke S. Gebow, editors Technical Report No. 68 United States Geological Survey Sonoran Desert Field Station The University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona USGS Sonoran Desert Field Station The University of Arizona, Tucson The Sonoran Desert Field Station (SDFS) at The University of Arizona is a unit of the USGS Western Ecological Research Center (WERC). It was originally established as a National Park Service Cooperative Park Studies Unit (CPSU) in 1973 with a research staff and ties to The University of Arizona. Transferred to the USGS Biological Resources Division in 1996, the SDFS continues the CPSU mission of providing scientific data (1) to assist U.S. Department of Interior land management agencies within Arizona and (2) to foster cooperation among all parties overseeing sensitive natural and cultural resources in the region. It also is charged with making its data resources and researchers available to the interested public. Seventeen such field stations in California, Arizona, and Nevada carry out WERC’s work. The SDFS provides a multi-disciplinary approach to studies in natural and cultural sciences. Principal cooperators include the School of Renewable Natural Resources and the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at The University of Arizona. Unit scientists also hold faculty or research associate appointments at the university. The Technical Report series distributes information relevant to high priority regional resource management needs. The series presents detailed accounts of study design, methods, results, and applications possibly not accommodated in the formal scientific literature. Technical Reports follow SDFS guidelines and are subject to peer review and editing. -

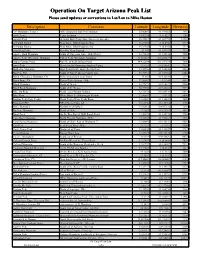

Peak List Please Send Updates Or Corrections to Lat/Lon to Mike Heaton

Operation On Target Arizona Peak List Please send updates or corrections to Lat/Lon to Mike Heaton Description Comment Latitude Longitude Elevation "A" Mountain (Tempe) ASU campus by Sun Devil Stadium 33.42801 -111.93565 1495 AAA Temp Temp Location 33.42234 -111.8227 1244 Agassiz Peak @ Snow Bowl Tram Stop (No access to peak) 35.32587 -111.67795 12353 Al Fulton Point 1 Near where SR260 tops the Rim 34.29558 -110.8956 7513 Al Fulton Point 2 Near where SR260 tops the rim 34.29558 -110.8956 7513 Alta Mesa Peak For Alta Mesa Sign-up 33.905 -111.40933 7128 Apache Maid Mountain South of Stoneman Lake - Hike/Drive? 34.72588 -111.55128 7305 Apache Peak, Whetstone Mountain Tallest Peak, Whetstone Mountain 31.824583 -110.429517 7711 Aspen Canyon Point Rim W. of Kehl Springs Point 34.422204 -111.337874 7600 Aztec Peak Sierra Ancha Mountains South of Young 33.8123 -110.90541 7692 Battleship Mountain High Point visible above the Flat Iron 33.43936 -111.44836 5024 Big Pine Flat South of Four Peaks on County Line 33.74931 -111.37304 6040 Black (Chocolate) Mountain, CA Drive up and park, near Yuma 33.055 -114.82833 2119 Black Butte, CA East of Palm Springs - Hike 33.56167 -115.345 4458 Black Mountain North of Oracle 32.77899 -110.96319 5586 Black Rock Mountain South of St. George 36.77305 -113.80802 7373 Blue Jay Ridge North end of Mount Graham 32.75872 -110.03344 8033 Blue Vista White Mtns. S. of Hannagan Medow 33.56667 -109.35 8000 Browns Peak (Four Peaks) North Peak of Four Peaks Range 33.68567 -111.32633 7650 Brunckow Hill NE of Sierra Vista, AZ 31.61736 -110.15788 4470 Bryce Mountain Northwest of Safford 33.02012 -109.67232 7298 Buckeye Mountain North of Globe 33.4262 -110.75763 4693 Burnt Point On the Rim East of Milk Ranch Point 34.40895 -111.20478 7758 Camelback Mountain North Phoenix Mountain - Hike 33.51463 -111.96164 2703 Carol Spring Mountain North of Globe East of Highway 77 33.66064 -110.56151 6629 Carr Peak S.