Gender, Race, Class and Other Implications for Hard Rock and Metal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phases of Irish History

¥St& ;»T»-:.w XI B R.AFLY OF THE UNIVERSITY or ILLINOIS ROLAND M. SMITH IRISH LITERATURE 941.5 M23p 1920 ^M&ii. t^Ht (ff'Vj 65^-57" : i<-\ * .' <r The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. University of Illinois Library • r m \'m^'^ NOV 16 19 n mR2 51 Y3? MAR 0*1 1992 L161—O-1096 PHASES OF IRISH HISTORY ^.-.i»*i:; PHASES OF IRISH HISTORY BY EOIN MacNEILL Professor of Ancient Irish History in the National University of Ireland M. H. GILL & SON, LTD. so UPPER O'CONNELL STREET, DUBLIN 1920 Printed and Bound in Ireland by :: :: M. H. Gill &> Son, • • « • T 4fl • • • JO Upper O'Connell Street :: :: Dttblin First Edition 1919 Second Impression 1920 CONTENTS PACE Foreword vi i II. The Ancient Irish a Celtic People. II. The Celtic Colonisation of Ireland and Britain . • • • 3^ . 6i III. The Pre-Celtic Inhabitants of Ireland IV. The Five Fifths of Ireland . 98 V. Greek and Latin Writers on Pre-Christian Ireland . • '33 VI. Introduction of Christianity and Letters 161 VII. The Irish Kingdom in Scotland . 194 VIII. Ireland's Golden Age . 222 IX. The Struggle with the Norsemen . 249 X. Medieval Irish Institutions. • 274 XI. The Norman Conquest * . 300 XII. The Irish Rally • 323 . Index . 357 m- FOREWORD The twelve chapters in this volume, delivered as lectures before public audiences in Dublin, make no pretence to form a full course of Irish history for any period. -

Nightshiftmag.Co.Uk @Nightshiftmag Nightshiftmag Nightshiftmag.Co.Uk Free Every Month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 299 September Oxford’S Music Magazine 2021

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 299 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2021 Gig, Interrupted Meet the the artists born in lockdown finally coming to a venue near you! Also in this comeback issue: Gigs are back - what now for Oxford music? THE AUGUST LIST return Introducing JODY & THE JERMS What’s my line? - jobs in local music NEWS HELLO EVERYONE, Festival, The O2 Academy, The and welcome to back to the world Bullingdon, Truck Store and Fyrefly of Nightshift. photography. The amount raised You all know what’s been from thousands of people means the happening in the world, so there’s magazine is back and secure for at not much point going over it all least the next couple of years. again but fair to say live music, and So we can get to what we love grassroots live music in particular, most: championing new Oxford has been hit particularly hard by the artists, challenging them to be the Covid pandemic. Gigs were among best they can be, encouraging more the first things to be shut down people to support live music in the back in March 2020 and they’ve city and beyond and making sure been among the very last things to you know exactly what’s going be allowed back, while the festival on where and when with the most WHILE THE COVID PANDEMIC had a widespread impact on circuit has been decimated over the comprehensive local gig guide Oxford’s live music scene, it’s biggest casualty is The Wheatsheaf, last two summers. -

Download PDF 8.01 MB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Imagining Scotland in Music: Place, Audience, and Attraction Paul F. Moulton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC IMAGINING SCOTLAND IN MUSIC: PLACE, AUDIENCE, AND ATTRACTION By Paul F. Moulton A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Paul F. Moulton defended on 15 September, 2008. _____________________________ Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Eric C. Walker Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Alison iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In working on this project I have greatly benefitted from the valuable criticisms, suggestions, and encouragement of my dissertation committee. Douglass Seaton has served as an amazing advisor, spending many hours thoroughly reading and editing in a way that has shown his genuine desire to improve my skills as a scholar and to improve the final document. Denise Von Glahn, Michael Bakan, and Eric Walker have also asked pointed questions and made comments that have helped shape my thoughts and writing. Less visible in this document has been the constant support of my wife Alison. She has patiently supported me in my work that has taken us across the country. She has also been my best motivator, encouraging me to finish this work in a timely manner, and has been my devoted editor, whose sound judgement I have come to rely on. -

DARKWOODS MAILORDER CATALOGUE October 2016

DARKWOODS MAILORDER CATALOGUE October 2016 DARKWOODS PAGAN BLACK METAL DI STRO / LABEL [email protected] www.darkwoods.eu Next you will find a full list with all available items in our mailorder catalogue alphabetically ordered... With the exception of the respective cover, we have included all relevant information about each item, even the format, the releasing label and the reference comment... This catalogue is updated every month, so it could not reflect the latest received products or the most recent sold-out items... please use it more as a reference than an updated list of our products... CDS / MCDS / SGCDS 1349 - Beyond the Apocalypse [CD] 11.95 EUR Second smash hit of the Norwegians 1349, nine outstanding tracks of intense, very fast and absolutely brutal black metal is what they offer us with “Beyond the Apocalypse”, with Frost even more a beast behind the drum set here than in Satyricon, excellent! [Released by Candlelight] 1349 - Demonoir [CD] 11.95 EUR Fifth full-length album of this Norwegian legion, recovering in one hand the intensity and brutality of the fantastic “Hellfire” but, at the same time, continuing with the experimental and sinister side of their music introduced in their previous work, “Revelations of the Black Flame”... [Released by Indie Recordings] 1349 - Hellfire [CD] 11.95 EUR Brutal third full-length album of the Norwegians, an immense ode to the most furious, powerful and violent black metal that the deepest and flaming hell could vomit... [Released by Candlelight] 1349 - Liberation [CD] 11.95 EUR Fantastic -

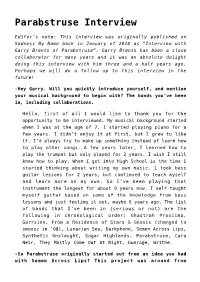

Parabstruse Interview

Parabstruse Interview Editor’s note: This interview was originally published on Sadness By Name back in January of 2010 as “Interview with Garry Brents of Parabstruse”. Garry Brents has been a close collaborator for many years and it was an absolute delight doing this interview with him three and a half years ago. Perhaps we will do a follow up to this interview in the future! -Hey Garry. Will you quickly introduce yourself, and mention your musical background to begin with? The bands you’ve been in, including collaborations. Hello, first of all I would like to thank you for the opportunity to be interviewed. My musical background started when I was at the age of 7. I started playing piano for a few years. I didn’t enjoy it at first, but I grew to like it. I’d always try to make up something instead of learn how to play other songs. A few years later, I learned how to play the trumpet but only played for 2 years. I wish I still knew how to play. When I got into High School is the time I started thinking about writing my own music. I took bass guitar lessons for 2 years, but continued to teach myself and learn more on my own. So I’ve been playing that instrument the longest for about 9 years now. I self-taught myself guitar based on some of the knowledge from bass lessons and just feeling it out, maybe 6 years ago. The list of bands that I’ve been in (serious or not) are the following in chronological order: Ghastrah Proxiima, Garrsinn, From a Residence of Stars & Gnosis (changed to smoosz in ’08), Lunarian Sea, Darkphone, Semen Across Lips, Synthetic Onslaught, Sugar Highlands, Parabstruse, Cara Neir, They Mostly Come Out At Night, bunrage, Writhe. -

Old Germanic Heritage in Metal Music

Lorin Renodeyn Historical Linguistics and Literature Studies Old Germanic Heritage In Metal Music A Comparative Study Of Present-day Metal Lyrics And Their Old Germanic Sources Promotor: Prof. Dr. Luc de Grauwe Vakgroep Duitse Taalkunde Preface In recent years, heathen past of Europe has been experiencing a small renaissance. Especially the Old Norse / Old Germanic neo-heathen (Ásatrú) movement has gained popularity in some circles and has even been officially accepted as a religion in Iceland and Norway among others1. In the world of music, this renaissance has led to the development of several sub-genres of metal music, the so-called ‘folk metal’, ‘Viking Metal’ and ‘Pagan Metal’ genres. Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my promoter, prof. dr. Luc de Grauwe, for allowing me to choose the subject for this dissertation and for his guidance in the researching process. Secondly I would like to thank Sofie Vanherpen for volunteering to help me with practical advice on the writing process, proof reading parts of this dissertation, and finding much needed academic sources. Furthermore, my gratitude goes out to Athelstan from Forefather and Sebas from Heidevolk for their co- operation in clarifying the subjects of songs and providing information on the sources used in the song writing of their respective bands. I also want to thank Cris of Svartsot for providing lyrics, translations, track commentaries and information on how Svartsot’s lyrics are written. Last but not least I want to offer my thanks to my family and friends who have pointed out interesting facts and supported me in more than one way during the writing of this dissertation. -

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

Running Head: NATIONAL IMAGERY in FINNISH FOLK METAL 1

Running head: NATIONAL IMAGERY IN FINNISH FOLK METAL 1 NATIONAL IMAGERY IN FINNISH FOLK METAL: Lyrics, Facebook and Beyond Renée Barbosa Moura Master‟s thesis Digital Culture University of Jyväskylä Department of Art and Culture Studies Jyväskylä 2014 NATIONAL IMAGERY IN FINNISH FOLK METAL 2 UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ Faculty Department Humanities Art and Culture Studies Author Renée Barbosa Moura Title National Imagery in FFM: Lyrics, Facebook and Beyond Subject Level Digital Culture MA Thesis Month and year Number of pages June 2014 90 pages Abstract Folk metal is a music genre originated from heavy metal music. For many artists and fans, folk metal is more than just music: it is a way of revitalising tradition. Folk metal is then a genre which is closely related to individual‟s cultural identities. As part of popular culture, heavy metal has been investigated for instance in the fields of cultural studies and psychology. Andrew Brown investigates how heavy metal emerged as subject for academic research. Deena Weinstein approaches heavy metal as culture and behaviour that is shared by individuals from different cultural backgrounds. However, subgenres like folk metal have not yet been explored in depth by academics. Analysing folk metal‟s nuances in specific national contexts would provide further knowledge on national cultures and identities. One example of folk metal reflecting elements of national culture is Finnish folk metal. The bands whose works belong to this genre usually draw from Finnish culture to compose their works, which usually feature stories from a variety of traditional sources such as the epic book Kalevala. Such stories are then transposed into new media, disseminating the artists‟ concept of Finnishness. -

Thematic Patterns in Millennial Heavy Metal: a Lyrical Analysis

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 Thematic Patterns In Millennial Heavy Metal: A Lyrical Analysis Evan Chabot University of Central Florida Part of the Sociology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Chabot, Evan, "Thematic Patterns In Millennial Heavy Metal: A Lyrical Analysis" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2277. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2277 THEMATIC PATTERNS IN MILLENNIAL HEAVY METAL: A LYRICAL ANALYSIS by EVAN CHABOT B.A. University of Florida, 2011 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Sociology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2012 ABSTRACT Research on heavy metal music has traditionally been framed by deviant characterizations, effects on audiences, and the validity of criticism. More recently, studies have neglected content analysis due to perceived homogeneity in themes, despite evidence that the modern genre is distinct from its past. As lyrical patterns are strong markers of genre, this study attempts to characterize heavy metal in the 21st century by analyzing lyrics for specific themes and perspectives. Citing evidence that the “Millennial” generation confers significant developments to popular culture, the contemporary genre is termed “Millennial heavy metal” throughout, and the study is framed accordingly. -

AGALLOCH and ANAAL NATHRAKH at the INFERNO FESTIVAL 2012!

AGALLOCH and ANAAL NATHRAKH at the INFERNO FESTIVAL 2012! The american avant garde folk metal band AGALLOCH and Britains most necro black metal band ANAAL NATHRAKH are the next band on the bill for the INFERNO festival 2012. Together with the legendary BORKANAGAR, ARCTURUS and WITCHERY the 2012 edition of the INFERNO METAL FESTIVAL will be extreme. The countdown to the true black easter has begun - Get ready for four unholy days - and a hell of lot of bands! THE INFERNO METAL FESTIVAL has become a true black Easter tradition for metal fans, bands and music industry from all over the world with nearly 50 concerts every year since the start back in 2001. The festival offers exclusive concerts in unique surroundings with some of the best extreme metal bands and experimental artists in the world, from the new and underground to the legendary giants. At INFERNO you meet up with fellow metalheads for four days of head banging, party, black- metal sightseeing and expos, horror films, art exhibitions and all the unholy treats your dark heart desires. THE INFERNO METAL FESTIVAL invites you all to the annual black Easter gathering of metal, gore and extreme in Oslo, Norway from April 4. -7.april 2011. - Four days and a hell of a lot of bands! AGALLOCH: Agalloch is an American metal band formed in 1995 in Portland, Oregon. The band is led by vocalist and guitarist John Haughm and so far have released four limited EPs, four full-length albums. Inspired from bandS like ULVER and KATATONIA, Agalloch performs a progressive and avant-garde style of folk metal that encompasses an eclectic range of tendencies including neofolk, post-rock, black metal and doom metal. -

Shrestha 1 Nityam Shrestha Dr. Ackerman CS 185C February 22

Shrestha 1 Nityam Shrestha Dr. Ackerman CS 185c February 22, 2017 Celtic Pagan Music saved by Technology, Creativity and Belief Technology is now an integral part of everyone’s day-to-day life. After the industrial revolution (mid 1700s) and the digital revolution (late 1950s) our lives have been significantly improved. People are healthier, communication is easier, transportation is safer and the world is improving and becoming a better place to live. But these improvements have also changed the way we view and enjoy arts. Advancing technology also brought us many new forms of arts like graffiti (spray can), game arts (mobile/ web/ VR), 3D animations (games, movies, VR), sculptures (3D printing), etc. But technology has also shown us, both the better and the worst sides of it. With all these technological advancements people are forgetting old cultures and their art forms. Most people today are more familiar with native ancient traditions of the different cultures of the world, but barely of Europe. The Native American tradition, the tribal religions of Africa, the sophistication of Hindu belief and practice and the more recently revived Japanese tradition, Shinto, are widely acknowledge as the authentic native animistic tradition of their respective areas. In marked contrast, the European native tradition, from the massive civilizations of Greece and Rome to the barley documented tribal systems of the Picts, the Finns and other norther margins of the continent, has seen as having been obliterated totally. The Shrestha 2 people forgotten here, are the Celtic pagans. Their culture was superseded first by Christianity and Islam and, more recently, by post-Christian humanism. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: April 28, 2006 I, Kristín Jónína Taylor, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Musical Arts in: Piano Performance It is entitled: Northern Lights: Indigenous Icelandic Aspects of Jón Nordal´s Piano Concerto This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Steven J. Cahn Professor Frank Weinstock Professor Eugene Pridonoff Northern Lights: Indigenous Icelandic Aspects of Jón Nordal’s Piano Concerto A DMA Thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College–Conservatory of Music 28 December 2005 by Kristín Jónína Taylor 139 Indian Avenue Forest City, IA 50436 (641) 585-1017 [email protected] B.M., University of Missouri, Kansas City, 1997 M.M., University of Missouri, Kansas City, 1999 Committee Chair: ____________________________ Steven J. Cahn, Ph.D. Abstract This study investigates the influences, both domestic and foreign, on the composition of Jón Nordal´s Piano Concerto of 1956. The research question in this study is, “Are there elements that are identifiable from traditional Icelandic music in Nordal´s work?” By using set theory analysis, and by viewing the work from an extramusical vantage point, the research demonstrated a strong tendency towards an Icelandic voice. In addition, an argument for a symbiotic relationship between the domestic and foreign elements is demonstrable. i ii My appreciation to Dr. Steven J. Cahn at the University of Cincinnati College- Conservatory of Music for his kindness and patience in reading my thesis, and for his helpful comments and criticism.