The Various Strands of Dalit Assertion in Punjab Karthik Venkatesh Jan 25, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3.029 Peer Reviewed & Indexed Journal IJMSRR E- ISSN

Research Paper IJMSRR Impact Factor: 3.029 E- ISSN - 2349-6746 Peer Reviewed & Indexed Journal ISSN -2349-6738 DALITS IN TRADITIONAL TAMIL SOCIETY K. Manikandan Sadakathullah Appa College, Tirunelveli. Introduction ‘Dalits in Traditional Tamil Society’, highlights the classification of dalits, their numerical strength, the different names of the dalits in various regions, explanation of the concept of the dalit, origin of the dalits and the practice of untouchabilty, the application of distinguished criteria for the dalits and caste-Hindus, identification of sub-divisions amongst the dalits, namely, Chakkiliyas, Kuravas, Nayadis, Pallars, Paraiahs and Valluvas, and the major dalit communities in the Tamil Country, namely, Paraiahs, Pallas, Valluvas, Chakkilias or Arundathiyars, the usage of the word ‘depressed classes’ by the British officials to denote all the dalits, the usage of the word ‘Scheduled Castes’ to denote 86 low caste communities as per the Indian Council Act of 1935, Gandhi’s usage of the word ‘Harijan’ to denote the dalits, M.C. Rajah’s opposition of the usage of the word ‘Harijan’, the usage of the term ‘Adi-Darvida’ to denote the dalits of the Tamil Country, the distribution of the four major dalit communities in the Tamil Country, the strength of the dalits in the 1921 Census, a brief sketch about the condition of the dalits in the past, the touch of the Christian missionaries on the dalits of the Tamil Country, the agrestic slavery of the dalits in the modern Tamil Country, the patterns of land control, the issue of agrestic servitude of dalits, the link of economic and social developments with the changing agrarian structure and the subsequent profound impact on the lives of the Dalits and the constructed ideas of native super-ordination and subordination which placed the dalits at the mercy of the dominant communities in Tamil Society’. -

Any Person May Make a Complaint About The

HIGH COURT OF CHHATTISGARH AT BILASPUR WRIT PETITION (C) No. 4944 of 2009 PETITIONER : Rajendra Singh (Arora). V E R S U S RESPONDENTS : State of Chhattisgarh & Others. PETITION UNDER ARTICLE 226/227 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA SB: Hon’ble Shri Satish K. Agnihotri, J. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Present: Shri Kishore Shrivastava, Senior Advocate with Shri Sanjay Tamrakar, Shri Ashish Shirvastava and Shri Anshuman Shrivastava, Advocates for the petitioner. Shri V.V.S.Moorthy, Deputy Advocate General for the State/ respondent No. 1, 2, 4 and 5. Dr. N.K.Shukla, Senior Advocate with Shri Aditya Khare, Advocates for the respondent No. 7 and 8. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- O R D E R (Delivered on 10th day of July, 2013) 1. The petitioner mainly challenges the order dated 23.07.2007 (Annexure P/14) passed by the High Power State Level Caste Scrutiny Committee i.e. respondent No. 3 (for short ‘the Committee’) wherein the petitioner has been found that he does not belong to “Lohar” i.e. Other Backward Class category, and also the subsequent order dated 28.08.2009 (Annexure P/2) wherein on the basis of the order dated 22.09.2008 (Annexure P/1) the petitioner was disqualified for a further period of five years in view of the provisions of section 19(2) of the Chhattisgarh Municipal Corporation Act, 1956 (for short 'the Act, 1956'). 2. The facts, in brief, are that the petitioner, in the year 2000, contested the election as Councillor from Ward No. 22, Municipal 2 Corporation, Bhilai, declaring himself as a member of “Lohar” community that comes within OBC category on the basis of social status certificate dated 10.04.2000 (Annexure P/3). -

Paper Teplate

Volume-04 ISSN: 2455-3085 (Online) Issue-04 RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary April -2019 www.rrjournals.com [UGC Listed Journal] Socio-political impacts of Dera Politics in Punjab 1Kuljit & *2Dawinder Kaur 1Student, Department of political science, Lovely Professional University, Phagwara (India) 2Assistant Professor, Department of political science, Lovely Professional University, Phagwara (India) ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT Article History This research is based upon the concept of Dera politics as a world-wide phenomenon with Published Online: 15 April 2019 special context to Punjab. Dera politics is most prevalent in the two states of Punjab and Haryana. The real root cause of Dera politics is the caste system which has not only divided Keywords one or two more states but the whole of India. Caste based communities have faced such Dera‟s, untouchability, superstitious, inequality, poverty. problems before independence and yet facing it till today. The Dera is divided between the upper caste and the lower caste. It is highly affecting the lives of the people in Punjab. *Corresponding Author Instead of solving the problems, the community it has created more of communal clashes. They must have started the Dera with a different motive. Like the upliftment of the lower Email: dawinder.22040[at]lpu.co.in caste people and their basic rights of entering the religion places was denied to them. Dera was made to fight for the rights of the minorities but later on, was used for the corrupt motives of baba Ram Rahim. But Punjab government has taken some essential steps in quelling the Dera politics, which was being run by baba Ram Rahim. -

E-Digest on Ambedkar's Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology

Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology An E-Digest Compiled by Ram Puniyani (For Private Circulation) Center for Study of Society and Secularism & All India Secular Forum 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Behind BEST Bus Depot, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 055. E-mail: [email protected], www.csss-isla.com Page | 1 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Preface Many a debates are raging in various circles related to Ambedkar’s ideology. On one hand the RSS combine has been very active to prove that RSS ideology is close to Ambedkar’s ideology. In this direction RSS mouth pieces Organizer (English) and Panchjanya (Hindi) brought out special supplements on the occasion of anniversary of Ambedkar, praising him. This is very surprising as RSS is for Hindu nation while Ambedkar has pointed out that Hindu Raj will be the biggest calamity for dalits. The second debate is about Ambedkar-Gandhi. This came to forefront with Arundhati Roy’s introduction to Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ published by Navayana. In her introduction ‘Doctor and the Saint’ Roy is critical of Gandhi’s various ideas. This digest brings together some of the essays and articles by various scholars-activists on the theme. Hope this will help us clarify the underlying issues. Ram Puniyani (All India Secular Forum) Mumbai June 2015 Page | 2 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Contents Page No. Section A Ambedkar’s Legacy and RSS Combine 1. Idolatry versus Ideology 05 By Divya Trivedi 2. Top RSS leader misquotes Ambedkar on Untouchability 09 By Vikas Pathak 3. -

Religion, Freedom and Escape of Women in African American and Indian

Koshy 1 Spice Sisters: Religion, Freedom and Escape of Women in African American and Indian Literatures A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the School Of Communication In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English By Lovely Koshy 3 May 2013 Koshy 2 Liberty University School of Communication Master of Arts in English _______________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chair Date Yaw Adu-Gyamfi, Ph.D. ______________________________________________________________________ First Reader Date Mark Schmidt, Ph.D. _______________________________________________________________________ Second Reader Date Clive McClelland, Ph. D. Koshy 3 Special Thanks to . My husband, Denny Koshy, for putting up with my strange schedules, stressful days, and cheering me on My children, Jonathan, David, Ruth and Jerusalem-Rose, for providing comic relief daily My parents, who coincidentally also celebrated fifty years in the ministry, for their legacy Dr. Yaw, for hours devoted to helping me present a holistic argument Family and friends, for prayers, support, and encouragement Koshy 4 Table of Contents Introduction: Spice Sisters: Religion, Freedom and Escape of Women in African American and Indian Literatures …………………………. ………………………………………….……...5 Chapter One: Amen, Sister! Religious Matriarch in Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun ………..............25 Chapter Two: Spicy Women in Tagore’s Short Stories……………………………………….…....…..38 Chapter Three: Hansberry and Tagore: Spice in Social Activism………………………………………..52 Chapter Four: Savoring the Spice through Hansberry and Tagore…………………. ……………….....67 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………….…..81 Koshy 5 Introduction Spice Sisters: Religion, Freedom, and Escape of Women in African American and Indian Literatures “When the world gets ugly enough – a woman will do anything for her family.” – Mama in A Raisin in the Sun . Lorraine Hansberry and Rabindranath Tagore are two authors whose contribution to literature goes beyond their giftedness as writers. -

Population Genetics for Autosomal STR Loci in Sikh Population Of

tics: Cu ne rr e en G t y R r e a t s i e d a e r r c e h Dogra, et al., Hereditary Genet 2015, 4:1 H Hereditary Genetics ISSN: 2161-1041 DOI: 10.4172/2161-1041.1000142 Research Article Open Access Population Genetics for Autosomal STR Loci in Sikh Population of Central India Dogra D1, Shrivastava P2*, Chaudhary R3, Gupta U2 and Jain T2 1Department of Biotechnology, Barkatullah University, Bhopal 462023, Madhya Pradesh, India 2DNA Fingerprinting Unit, State Forensic Science Laboratory, Sagar 470001, Madhya Pradesh, India 3Biotechnology Division, Department of Zoology, Government Motilal Vigyan Mahavidyalaya, Bhopal 462023, Madhya Pradesh, India *Corresponding author: Pankaj Shrivastava, DNA Fingerprinting Unit, State Forensic Science Laboratory, Sagar-470001, Madhya Pradesh, India, Tel: 94243 71946, E- mail: [email protected] Rec date: February 4, 2015, Acc date: February 23, 2015, Pub date: February 26, 2015 Copyright: © 2015 Dogra D, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract This study is an attempt to generate genetic database for three endogamous populations of Sikh population (Arora, Jat and Ramgariha) of Central India. The analysis of eight autosomal STR loci (D16S539, D7S820, D13S317, FGA, CSF1PO, D21S11, D18S51, and D2S1338) was done in 140 unrelated Sikh individuals. In all the three studied populations, all loci were in Hardy -Weinberg equilibrium except at locus FGA in Ramgariha Sikh and locus D16S539 in Arora Sikh. -

IJSA December 2008

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SIKH AFFAIRS NOVEMBER 2008 Volume 18 No. 2 Published By: The Sikh Educational Trust Box 60246 University of Alberta Postal Outlet EDMONTON, Alberta CANADA ISSN 1481-5435 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.yahoogroups.com/group/IntJSA INTERNATIONAL JOURNA L OF SIKH AFFAIRS Editorial Board Founded by: Dr Harjinder Singh Dilgeer Editorial Advisors Dr S S Dhami, MD Dr B S Samagh Dr Surjit Singh Prof Gurtej Singh, IAS Dr R S Dhadli New York, USA Ottawa, CANADA Williamsville, NY Chandigarh Troy, USA J S Dhillon “Arshi” M S Randhawa Usman Khalid Dr Sukhjit Kaur Gill Gurmit Singh Khalsa MALAYSIA Ft. Lauderdale, FL Editor, LISA Journal Chandigarh AUSTRALIA Dr Sukhpreet Singh Udhoke PUNJAB Managing Editor and Acting Editor in Chief: Dr Awatar Singh Sekhon The Sikh Educational Trust Box 60246, University of Alberta Postal Outlet EDMONTON, AB T6G 2S5 CANADA E-mail:<[email protected]> NOTE: Views presented by the authors in their contributions in the journal are their own and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Editor in Chief, the Editorial Advisors, or the publisher. SUBCRIPTION: US$75.00 per anum plus 6% GST plus postage and handling (by surface mail) for institutions and multiple users. Personal copies: US$25.00 plus &% GST plus postage and handling (surface mail). Orders for the current and forthcoming issues may be placed with the Sikh Educational Trust, Box 60246, Univ of AB Postal Outlet, EDMONTON, AB T6G 2S5 CANADA. E-mail: [email protected] The Sikh Leaders, Freedom Fighters and Intellectuals To bring an end to tyranny it is a must to punish the terrorist -Baba (General) Banda Singh Bahadar Sikhs have only two options: slavery of the Hindus or struggle for their lost sovereignty and freedom -Sirdar Kapur Singh, ICS, MP, MLA and National Professor of Sikhism I am not afraid of physical death; moral death is death in reality Saint-soldier Jarnail Singh Khalsa Martyrdom is our orn a m e n t -Bhai Awtar Singh Brahma (General) We do not fear the terrorist Hindu regime. -

Htts-Newsletter-Fina

WINTER 2012 Bhakti patra First Hindu Temple in White Plains coming soon! A group of dedicated and determined Hindu citizens of our community have come together with a vision and a dream of building a unifying monument to our traditions – right here in the heart of Westchester! This dream Hindu Temple of Tristates has grown to reality and has culminated in the purchase of a Bhoomi Pooja pristine parcel of land to construct Westchester dignitaries applaud and welcome the Hindu Temple of Tristates. The property, located at our temple in Westchester! rd 390 North Street in White Plains is Saturday, October 23 was a very momentous day for all Hindus 1.75 acres of flat landscaped land in Westchester! The Trustees of the Hindu Temple of Tristates that is already zoned for religious along with more than 70 dedicated volunteers organized the buildings. Bhoomi Pooja for land, which will be the home of our Temple. The occasion was graced by more than 500 people! Dignitaries that included Hon. Mayor Amicone of Yonkers, County Executive Robert Astorino, Hon. Mayor Tom M. Roach of White Plains, Mayor Joseph Delfino, and many others attended the Pooja and applauded and welcomed the addition of this monument in the heart of Westchester. Mayor Amicone and County Exec. Robert Astorino also presented the Trustees with Proclamations commemorating the occasion! Visit our Facebook page at: http://www.facebook.com/pages/Hindu-Temple-of- Tristates/207947092572092 to view the proclamations and photographs from this day. WINTER 2012 BHAKTIBhakti PATRApatra WINTER 2012 LEAVE A LEGACY FOR YOUR LOVED ONES! Please complete the above form along with a check made out to “Hindu Temple of Tristates” and mail to 77 Knollwood Rd., White Plains, NY 10607. -

Economic and Political Change and Caste Relations in Tamil Nadu Early in the 21St Century

Privilege in Dispute: Economic and Political Change and Caste Relations in Tamil Nadu Early in the 21st Century John Harriss Simons Papers in Security and Development No. 44/2014 | September 2015 Simons Papers in Security and Development No. 44/2015 2 The Simons Papers in Security and Development are edited and published at the School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University. The papers serve to disseminate research work in progress by the School’s faculty and associated and visiting scholars. Our aim is to encourage the exchange of ideas and academic debate. Inclusion of a paper in the series should not limit subsequent publication in any other venue. All papers can be downloaded free of charge from our website, www.sfu.ca/internationalstudies. The series is supported by the Simons Foundation. Series editor: Jeffrey T. Checkel Managing editor: Martha Snodgrass Harriss, John, Privilege in Dispute: Economic and Political Change and Caste Relations in Tamil Nadu Early in the 21st Century, Simons Papers in Security and Development, No. 44/2015, School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, September 2015. ISSN 1922-5725 Copyright remains with the author. Reproduction for other purposes than personal research, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), the title, the working paper number and year, and the publisher. Copyright for this issue: John Harriss, jharriss(at)sfu.ca. School for International Studies Simon Fraser University Suite 7200 - 515 West Hastings Street Vancouver, BC Canada V6B 5K3 Privilege in Dispute: Caste Relations in Tamil Nadu 3 Privilege in Dispute: Economic and Political Change and Caste Relations in Tamil Nadu Early in the 21st Century Simons Papers in Security and Development No. -

Autobiography As a Social Critique: a Study of Madhopuri's Changiya Rukh and Valmiki's Joothan

AUTOBIOGRAPHY AS A SOCIAL CRITIQUE: A STUDY OF MADHOPURI’S CHANGIYA RUKH AND VALMIKI’S JOOTHAN A Dissertation submitted to the Central University of Punjab For the Award of Master of Philosophy in Comparative Literature BY Kamaljeet kaur Administrative Guide: Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana Dissertation Coordinator: Dr. Amandeep Singh Centre for Comparative Literature School of Languages, Literature and Culture Central University of Punjab, Bathinda March, 2012 CERTIFICATE I declare that the dissertation entitled ‘‘AUTOBIOGRAPHY AS A SOCIAL CRITIQUE: A STUDY OF MADHOPURI’S CHANGIYA RUKH AND VALMIKI’S JOOTHAN’’ has been prepared by me under the guidance of Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana, Administrative Guide, Acting Dean, School of Languages, Literature and Culture and Dr. Amandeep Singh, Assistant Professor, Centre for Comparative Literature, Central University of Punjab. No part of this dissertation has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. (Kamaljeet Kaur) Centre for Comparative Literature School of Languages, Literature and Culture Central University of Punjab Bathinda-151001 Punjab, India Date: i CERTIFICATE I certify that KAMALJEET KAUR has prepared her dissertation entitled “AUTOBIOGRAPHY AS A SOCIAL CRITIQUE: A STUDY OF MADHOPURI’S CHANGIYA RUKH AND VALMIKI’S JOOTHAN”, for the award of M.Phil. degree of the Central University of Punjab, under my guidance. She has carried out this work at the Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab. (Dr. Amandeep Singh) Assistant Professor Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. Date: (Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana) Acting Dean Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. -

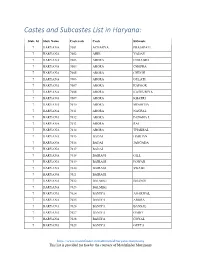

Castes and Subcastes List in Haryana

Castes and Subcastes List in Haryana: State Id State Name Castecode Caste Subcaste 7 HARYANA 7001 ACHARYA PRAJAPATI 7 HARYANA 7002 AHIR YADAV 7 HARYANA 7003 ARORA CHHABRA 7 HARYANA 7004 ARORA CHOPRA 7 HARYANA 7005 ARORA CHUGH 7 HARYANA 7006 ARORA GULATI 7 HARYANA 7007 ARORA KAPOOR 7 HARYANA 7008 ARORA KATHURIYA 7 HARYANA 7009 ARORA KHATRI 7 HARYANA 7010 ARORA MINOCHA 7 HARYANA 7011 ARORA NAGPAL 7 HARYANA 7012 ARORA PANGHA L 7 HARYANA 7013 ARORA RAI 7 HARYANA 7014 ARORA THAKRAL 7 HARYANA 7015 BADAI HARIJAN 7 HARYANA 7016 BADAI JANGADA 7 HARYANA 7017 BADAI 7 HARYANA 7018 BAIRAGI GILL 7 HARYANA 7019 BAIRAGI POWAR 7 HARYANA 7020 BAIRAGI SWAMI 7 HARYANA 7021 BAIRAGI 7 HARYANA 7022 BALMIKI BHANGI 7 HARYANA 7023 BALMIKI 7 HARYANA 7024 BANIYA AGARWAL 7 HARYANA 7025 BANIYA ARORA 7 HARYANA 7026 BANIYA BANSAL 7 HARYANA 7027 BANIYA GARG 7 HARYANA 7028 BANIYA GOYAL 7 HARYANA 7029 BANIYA GUPTA https://www.matchfinder.in/matrimonial/haryana-matrimony This list is provided for free by the courtesy of Matchfinder Matrimony 7 HARYANA 7030 BANIYA JAIN 7 HARYANA 7031 BANIYA JINDAL 7 HARYANA 7032 BANIYA KANSAL 7 HARYANA 7033 BANIYA MAHAJAN 7 HARYANA 7034 BANIYA RANA 7 HARYANA 7035 BANIYA SHAHU 7 HARYANA 7036 BANIYA SINGLA 7 HARYANA 7037 BANIYA 7 HARYANA 7038 BANNSA GARG 7 HARYANA 7039 BAORI 7 HARYANA 7040 BARHAI DHIMAN 7 HARYANA 7041 BARHAI GARG 7 HARYANA 7042 BARHAI KHATI 7 HARYANA 7043 BARHAI SHARMA 7 HARYANA 7044 BARHAI VISHWAKARMA 7 HARYANA 7045 BAWARIA DABLA 7 HARYANA 7046 BAZIGAR BADHAI 7 HARYANA 7047 BHAT ACHARYA 7 HARYANA 7048 BHAT SHARMA 7 HARYANA -

Punjab Public Works Department (B&R)

Punjab Public Works Department (B&R) Establishment Chart ( Dated : 17.09.2021 ) Chief Engineer (Civil) S. Name of Officer/ Email Qualification Present Place of Posting Date of Home Date of No address/ Mobile No. Posting District Birth 1. Er. Arun Kumar M.E. Chief Engineer (North) 12.11.2018 Ludhiana 28.11.1964 [email protected] Incharge of:- [email protected] Construction Circle, Amritsar 9872253744 and Hoshiarpur from 08.03.2019 And Additional Charge Chief Engineer (Headquarter-1), and Chief Engineer (Headquarter-2) and Nodal Officer (Punjab Vidhan Sabha Matters)(Plan Roads) 2. Er. Amardeep Singh Brar, B.E.(Civil) Chief Engineer (West) 03.11.2020 Faridkot 25.03.1965 Chief Engineer, Incharge of: [email protected] Construction Circle Bathinda, and 9915400934 Ferozepur 3. Er.N.R.Goyal, Chief Engineer (South) 03.11.2020 Fazilka 15.05.1964 Chief Engineer Incharge of: [email protected] Construction Circle Patiala - 1 and [email protected] Sangrur, Nodal Officer –Link [email protected] Roads,PMGSY & NABARD 9356717117 Additional Charge Chief Engineer (Quality Assurance) from 19.04.2021 & Chief Vigilance Officer of PWD (B&R) Chief Engineer (NH) from 20.08.2021 Incharge of: National Highway Circle Amritsar, 4. Er.B.S.Tuli, M.E.(Irrigation) ChiefChandigarh, Engineer Fe (Centrozepurral) and Ludhiana 03.11.2020 Ludhiana 15.09.1964 Chief Engineer and Hydraulic Incha rge of: [email protected] Structure) Construction Circle No. 1 & 2 Jalandhar., 9814183304 Construction Circle Pathankot. Nodal Officer (Railways) from 03.11.2020 , Jang-e-Azadi Memorial, Kartarpur and Works under 3054 & 5054 Head 5.