Arguments of Mass Confusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ﺻﺪام ﺣﺴﻴﻦ :Saddam Hussein Abd al-Majid al-Tikriti (/hʊˈseɪn/;[5] Arabic Marshal Ṣaddām Ḥusayn ʿAbd al-Maǧīd al-Tikrītī;[a] 28 April ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻤﺠﻴﺪ اﻟﺘﻜﺮﻳﺘﻲ 1937[b] – 30 December 2006) was President of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 Saddam Hussein ﺻﺪام ﺣﺴﻴﻦ April 2003.[10] A leading member of the revolutionary Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party, and later, the Baghdad-based Ba'ath Party and its regional organization the Iraqi Ba'ath Party—which espoused Ba'athism, a mix of Arab nationalism and socialism—Saddam played a key role in the 1968 coup (later referred to as the 17 July Revolution) that brought the party to power inIraq . As vice president under the ailing General Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, and at a time when many groups were considered capable of overthrowing the government, Saddam created security forces through which he tightly controlled conflicts between the government and the armed forces. In the early 1970s, Saddam nationalized oil and foreign banks leaving the system eventually insolvent mostly due to the Iran–Iraq War, the Gulf War, and UN sanctions.[11] Through the 1970s, Saddam cemented his authority over the apparatus of government as oil money helped Iraq's economy to grow at a rapid pace. Positions of power in the country were mostly filled with Sunni Arabs, a minority that made up only a fifth of the population.[12] Official portrait of Saddam Hussein in Saddam formally rose to power in 1979, although he had already been the de 1979 facto head of Iraq for several years. -

Saddam Hussein, Saddam Hussein Was the President of Iraq

Animal Farm Research Chapter.3 By: Zion and Caeleb The world leader we picked was Saddam Hussein, Saddam Hussein was the president of Iraq. He was born on April 28, 1937, in Al-Awja Iraq. Hussein was raised by his mother, her second husband Ibrahim alHassan and her brother Khairallah Talfah.Hussein's first wife, Sajida, was his first cousin, the daughter of his maternal uncle Khairallah Talfah. Many of Hussein's family members were part of his regime. Brotherinlaw Brig. General Adnan Khairallah was Minister of Defense. Sonsinlaw General Hussein Kamel, husband to Raghad Hussein, led Iraq's nuclear, chemical and biological weapons program and his brother, Colonel Saddam Kamel, husband to Rana Hussein, was in charge of the presidential security forces. Eldest son Uday was head of the Iraqi Olympic Committee and younger son Qusay was head of the Internal Security Forces. And halfbrother Busho Ibrahim was the Deputy Minister of Justice. 1956 Takes part in an unsuccessful coup to overthrow King Faisal II and Prime Minister Nuri asSaid.1957 Hussein formally joins the Baath Socialist Party.July 14, 1958 King Faisal is killed in a coup led by Abdul Karim Kassem.October 1959 Hussein and others attack the motorcade of Abdul Karim Kassem. The assassination attempt fails and most of the attackers are killed. Hussein escapes and flees to Syria. Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser hears of Hussein's exploits and arranges for him to travel to Cairo.February 8, 1963 Kassem is overthrown and executed, and the Baath Party takes over. -

Dubya's Foreign Policy

Operation Iraqi Freedom President George W. Bush Stage I: The Conventional War General Tommy Franks Bombing Campaign: Shock and Awe March 19, 2003 1,700 air sorties The Air War World War II Persian Gulf War 3,000 sorties for 1 target 10 sorties for 1 target Iraqi Freedom 1 plane for 10 targets Trying to Fight a Cleaner War Goal: Limit Civil Destruction JDAMS (Joint Directed Attack Munitions) E-Bombs Bugsplat American Air Superiority No American soldier has been killed by an enemy aircraft since World War II Ground War –March 20 The Battle Plan Get to Baghdad and Take Out Saddam Rumsfeld Doctrine (light and fast) International Help Country Troop Amount United States 150,000 United Kingdom 46,000 Australia 2,000 Poland 200 Fear of Chem / Bio Weapons Attack Fear of getting “slimed” Iraqi Tanks in Iraqi Freedom • About 24 Iraqi tanks out of 800 left Only 9 Iraqi oil well fires No Easy Task Operation Iraqi Freedom Expected Length: 120 days Actual Length: 21 Days (Conventional War) Cost: $917,744,361.55 (46 minutes 10 ½ seconds) Learning Lessons from Vietnam Embedded reporters No Body Count “We don’t do body counts” –Tommy Franks Fall of Saddam’s Statue April 3, 2003 Saddam’s Statue Victory in Iraq (V-I Day) -May 1, 2003 Major Combatant Operations in Iraq Have Ended Saddam’s Sons: Uday and Qusay Uday and Qusay Mosul (July 22, 2003) The End of Uday and Qusay Mosul (July 22, 2003) The End of Uday and Qusay Mosul (July 22, 2003) How did US forces locate the Hussein Brothers? • Nawaf al-Zaydan – distant relative of Saddam – homeowner – Brother and 3 other relatives killed • Granted US citizenship and left Iraq • Probably $30 million richer Operation Red Dawn (Tikrit) Captured -December 13, 2003 Stage 1: So Far So Good . -

CEU Spring2004 Full

PERSON OF THE YEAR The American Soldier: Defender of Freedom They swept across Iraq and conquered it in 21 days. They caught Saddam Hussein. They are the face of America, its might and good will, in a region unused to democracy. The U.S. G.I. is Time’s Person of the Year By NANCY GIBBS winter wrapped in yellow ribbons and duct tape. But in a year when it felt at times as if we had odern history has a way of being nothing in common anymore, we were united in modest with its gifts and blunt with its this hope: that our men and women at arms might reckonings. Good news comes like a soon come safely home, because their job was breeze you feel but don’t notice; the done. They are the bright, sharp instrument of a markets are up, the air is cleaner, we’re blunt policy, and success or failure in a war unlike Mbeating heart disease. It is the bad news that any in history ultimately rests with them. comes with a blast or a crash, to For their uncommon skills stop us in mid-sentence to stare and service, for the choices at the TV, and shudder. each one of them has made and Maybe that’s why we are the ones still ahead, for the startled by gratitude in the sea- challenge of defending not only son of peace. To have pulled our freedoms but those barely Saddam Hussein from his hole stirring half a world away, the in the ground brings the possi- American soldier is Time’s Per- bility of pulling an entire coun- son of the Year. -

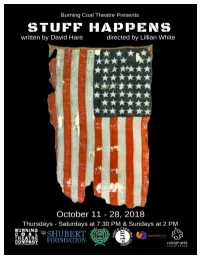

Study-Guide-For-STUFF-HAPPENS

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION AND THE RATIONALE FOR THE INVASION OF IRAQ One of the most weighty justifications for the United States' 2003 invasion of the Iraqi Republic was the pursuit of Weapons of Mass Destruction (hereafter referred to WMD) by the regime of President Saddam Hussein in violation of United Nations Security Council Resolutions 686 & 687. The potential for the Iraqi regime to develop nuclear capability, or that it already held chemical and biological weapons, sat at the forefront of President President George W. Bush Gives a Speech in Cincinatti George W. Bush's rhetoric. In his October 7, 2002 speech at the Cincinatti Museum Center, Bush noted: Tonight I want to take a few minutes to discuss a grave threat to peace, and America's determination to lead the world in confronting that threat. The threat comes from Iraq. It arises directly from the Iraqi regime's own actions -- its history of aggression, and its drive toward an arsenal of terror. Eleven years ago, as a condition for ending the Persian Gulf War, the Iraqi regime was required to destroy its weapons of mass destruction, to cease all development of such weapons, and to stop all support for terrorist groups. The Iraqi regime has violated all of those obligations. It possesses and produces chemical and biological weapons. It is seeking nuclear weapons. It has given shelter and support to terrorism, and practices terror against its own people.1 Or in his March 19, 2003 address to the nation from the Oval Office he began: My fellow citizens, at this hour, American and coalition forces are in the early stages of military operations to disarm Iraq, to free its people and to defend the world from grave danger. -

The Production and Circulation of Propaganda

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RMIT Research Repository The Only Language They Understand: The Production and Circulation of Propaganda A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Christian Tatman BA (Journalism) Hons RMIT University School of Media and Communication College of Design and Social Context RMIT University February 2013 Declaration I Christian Tatman certify that except where due acknowledgement has been made, the work is that of the author alone; the work has not been submitted previously, in whole or in part, to qualify for any other academic award; the content of the thesis is the result of work which has been carried out since the official commencement date of the approved research program; any editorial work, paid or unpaid, carried out by a third party is acknowledged; and, ethics procedures and guidelines have been followed. Christian Tatman February 2013 i Acknowledgements I would particularly like to thank my supervisors, Dr Peter Williams and Associate Professor Cathy Greenfield, who along with Dr Linda Daley, have provided invaluable feedback, support and advice during this research project. Dr Judy Maxwell and members of RMIT’s Research Writing Group helped sharpen my writing skills enormously. Dr Maxwell’s advice and the supportive nature of the group gave me the confidence to push on with the project. Professor Matthew Ricketson (University of Canberra), Dr Michael Kennedy (Mornington Peninsula Shire) and Dr Harriet Speed (Victoria University) deserve thanks for their encouragement. My wife, Karen, and children Bethany-Kate and Hugh, have been remarkably patient, understanding and supportive during the time it has taken me to complete the project and deserve my heartfelt thanks. -

Flyer News, Vol. 58, No. 02

UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON VOL. 58 NO. 2 FRIDAY SEPT. 3, 2010 An end in sight? ANNA BEYERLE News Editor President Barack Obama called for an end to the United States combat in Iraq in a live press confer- ence from the Oval Office Tuesday, Aug. 31. Obama’s announcement came a little over a week after the last combat troops pulled out of Iraq on Thurs., Aug. 19, according to a Washington Post ar- ticle. About 50,000 non-combat brigades will remain in the country, mainly to train Iraqi soldiers. Both the U.S. and Iraqi governments have agreed these forces will close their operations and leave Iraq be- fore Dec. 31, 2011. “We’ve done the best job we could do,” said Broth- er Raymond Fitz, former University of Dayton pres- ident and professor in the political science depart- ment. “Now we have to depend on Iraq to follow through.” See War on p. 5 FLYER NEWS PHOTO Mar. 19, 2003 Dec. 14, 2003 Jan. 12, 2005 Nov. 27, 2008 Aug. 19, 2010 President George W. Bush U.S. troops capture Saddam U.S. inspectors confirm that The Iraqi government The last group of combat calls for an invasion of Iraq Hussein in Ad-Dawr, Iraq, no WMDs were found in Iraq, passes a security agreement brigades leaves Iraq. to search for weapons of during Operation Red Dawn. and the search for them is to ask the U.S. to leave the mass destruction. called off. country by the end of 2011. Aug. 31, 2010 President Obama announces the official end of combat in Iraq. -

Games of Empire Electronic Mediations Katherine Hayles, Mark Poster, and Samuel Weber, Series Editors

Games of Empire Electronic Mediations Katherine Hayles, Mark Poster, and Samuel Weber, Series Editors 29 Games of Empire: Global Capitalism and Video Games Nick Dyer- Witheford and Greig de Peuter 28 Tactical Media Rita Raley 27 Reticulations: Jean-Luc Nancy and the Networks of the Political Philip Armstrong 26 Digital Baroque: New Media Art and Cinematic Folds Timothy Murray 25 Ex- foliations: Reading Machines and the Upgrade Path Terry Harpold 24 Digitize This Book! The Politics of New Media, or Why We Need Open Access Now Gary Hall 23 Digitizing Race: Visual Cultures of the Internet Lisa Nakamura 22 Small Tech: The Culture of Digital Tools Byron Hawk, David M. Rieder, and Ollie Oviedo, Editors 21 The Exploit: A Theory of Networks Alexander R. Galloway and Eugene Thacker 20 Database Aesthetics: Art in the Age of Information Overfl ow Victoria Vesna, Editor 19 Cyberspaces of Everyday Life Mark Nunes 18 Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture Alexander R. Galloway 17 Avatars of Story Marie-Laure Ryan 16 Wireless Writing in the Age of Marconi Timothy C. Campbell 15 Electronic Monuments Gregory L. Ulmer 14 Lara Croft: Cyber Heroine Astrid Deuber- Mankowsky 13 The Souls of Cyberfolk: Posthumanism as Vernacular Theory Thomas Foster 12 Déjà Vu: Aberrations of Cultural Memory Peter Krapp 11 Biomedia Eugene Thacker 10 Avatar Bodies: A Tantra for Posthumanism Ann Weinstone 9 Connected, or What It Means to Live in the Network Society Steven Shaviro 8 Cognitive Fictions Joseph Tabbi 7 Cybering Democracy: Public Space and the Internet Diana Saco 6 Writings Vilém Flusser 5 Bodies in Technology Don Ihde 4 Cyberculture Pierre Lévy 3 What’s the Matter with the Internet? Mark Poster 2 High Techne¯: Art and Technology from the Machine Aesthetic to the Posthuman R. -

Gregory Therel Esplin

Double or Nothing: The Uncanny State of Post-9.11 America Gregory Therel Esplin Talk about déjà vu all over again! If any word describes the contemporary situation of the United States after the attacks of September 11, 2001, it would be uncanny. The uncanny is reflected even in the details of the World Trade Center’s destruction: everything related to the incident seems come in doubles. It occurred on the date in which the number one is repeated twice: 11. The United States President in ‘01 was George Bush. Not the first one, but the second: Bush II. And then of course there is America’s involvement in another September 11: the one that occurred in 1973 when a U.S.-supported junta overthrew the democratically elected, left-wing President of Chile, Salvador Allende, ushering in years of right- wing terrorism which left thousands dead. A feeling of eerie repetition also surrounds September 11, since this was the second time Islamic fundamentalists attacked the WTC, the first being the 1993 truck bombing of the North Tower which left six dead but failed to bring down the structure. Finally, of course, there is the “double” nature of the Twin Towers themselves. Dominating the skyline of lower Manhattan, the Towers were an uncanny thing to behold. It was not so much their height that invoked a feeling of the sublime, but rather their repetition as imposing duplicates. They were officially referred to as One and Two World Trade Center, but popularly they were known as the Twin Towers. It was not enough to merely build the tallest building in existence. -

Preli Fe Vrier Preli 14 Mai 2011.Qxd

12 DEAUVILLE 1DEAUVILLE2 Vente mixte Lundi 13 février Février Vente mixte Vente en association avec Vendeurs_Liste_vendeurs_14_05.qxd 19/01/12 08:40 Page53 Vendeurs Index to vendors Ordre alphabétique - Alphabetical order Vendeur Lot S Nom Père Mère Box Pdt Baltromei....................0257 F. WILD TEMPTATION C 177 CAE Bary ..........................100 bis F. ALCHIMIA A 101 CAE Baudouin....................0004 M. VADASIN E 004 E Berlais........................0195 F. ALIZE DU BERLAIS B 129 Maiden .................................0265 F. AGATHE DU BERLAIS B 130 Maiden Bernesq......................0024 F. VERY BEST A 082 Maiden .................................0047 F. MISS VIC A 083 J. .................................0055 F. LE HAVRE FOLIE DANSE A 084 YLS .................................0069 F. GOLD WIND A 085 J. .................................0103 F. BLUE BAY DOLOISE A 086 J. .................................0109 F. MONDADOUN A 087 J. .................................0226 F. GOLD CLASSIC A 088 J. .................................0227 M. CREACHADOIR SPICY GIRL A 089 YLS .................................0252 F. ARTISTE ROYAL TUNE A 090 YLS .................................0261 F. BURGAUDINE A 091 J. Bidgood .....................0126 F. GOLDEN ROSE C 258 CAE .................................0276 F. BUGSY C 259 CAE Bois Carrouges ...........0044 F. TEMPETE TROPICALE C 250 J. Boschet ......................0264 F. SHARK BAY C 286 J. Boutin ........................0113 F. LADY ROCKET B 136 Maiden Cadran ......................0043 F. FLAGSHIP C 178 CAE .................................0127 F. LIZZY’S CAT C 179 J. .................................0186 F. KING’S BEST OMONIA C 180 YLS .................................0212 M. NAAQOOS ROSEANNA C 181 YLS .................................0245 F. TIPPERARY C 182 J. .................................0256 F. ISULA DI ISULA C 183 J. Camp Bénard .............0098 F. JOIE DE MAI A 040 J. .................................0119 F. COTTINGLEY FAIRY A 041 Maiden .................................0120 F. TUNGUSKA A 042 J. -

MND-B Soldiers, Sailor Turn Horror of 'Pile,'

VOL. 2, NO. 21 MULTI-NATIONAL DIVISION - BAGHDAD “STEADFAST AND LOYAL” September 29, 2008 MND-B Soldiers, Sailor turn horror of ‘Pile,’ MND-B Soldiers reinforce Baghdad stability during Sept. 11 into motivation to serve nation Ramadan By Staff Sgt. Brent Williams 1st BCT PAO, 4th Inf. Div. FORWARD OPERATING BASE FALCON, Iraq – The information flyer informs the Iraqi man that the suspect is wanted for crimes committed against the Iraqi people. The award for arresting this ter- rorist, $10,000, will be paid im- mediately if the information provided leads to the arrest of the reputed spe- cial groups cell leader known to operate in south- ern Baghdad. The Soldiers Photo by Staff Sgt. Brent Williams of the 1st Bri- Sgt. Julio Tirado, an infantry gade Combat team leader and 1st Brigade Team, 4th In- Combat Team, 4th Infantry Di- fantry Division, vision, MND-B, patrols outside working with of local shops and business Iraqi Security Sep. 6 in the Bayaa commu- Forces, continue nity of the Rashid district in to distribute in- southern Baghdad. formation flyers Photo by Staff Sgt. Brock Jones, MND-B PAO and posters that encourage Iraqi citizens to join in MND-B Soldiers raise flags during the 4th Infantry Division and Multi-National Division – Baghdad Patriot Day Obser- the fight against special groups criminals and ter- vance held in front of the division headquarters Sept. 11. rorists. The National Police of the 2nd Battalion, 5th By Staff Sgt. Brock Jones “During 9-11, I was a first responder,” said Juan Vega, a Bde., 2nd NP Div., attribute a large portion of their MND-B PAO native of Bronx, N.Y. -

© Osprey Publishing • IRAQ FULL CIRCLE from Shock and Awe to the Last Combat Patrol

© Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com IRAQ FULL CIRCLE From Shock and Awe to the Last Combat Patrol COL. DARRON L. WRIGHT © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com NOT FOR FAME OR REWARD, NOT FOR PLACE OR FOR RANK, NOT LURED BY AMBITION OR GOADED BY NECESSITY, BUT IN SIMPLE OBEDIENCE TO DUTY AS THEY UNDERSTOOD IT, THESE MEN SUFFERED ALL, SACRIFICED ALL, DARED ALL, AND DIED. —Confederate Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery I dedicate this book first and foremost to my loving wife Wendy and my amazing children Dillon, Chloe, and Kyle, for enduring all the months and years that I was forward deployed doing what I love to do. To my mom, stepfather, brother, sister, and their families, thanks for all your love and support over the years. To all the men and women who wear the uniform both past and present defending democracy abroad and serving as the beacon of freedom for America, you represent less than 1 percent of our nation’s population who have stepped forward to serve a cause greater than yourselves. You all are heroes and deserve the highest regard and praise that our nation can bestow upon you. You are America’s finest. To the brave and courageous soldiers of 1st Battalion –8th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Brigade Combat Team–4th Infantry Division, 4th Brigade Combat Team–4th Infantry Division, 1st Battalion Airborne–509th Infantry, and the 4th Stryker Brigade Combat Team–2nd Infantry Division, thanks for your service and most of all your sacrifice. You made your mark on this war at different stages and times over the past years, but, most noteworthy, you brought freedom and hope to a country that only knew tyranny and oppression.