Cultural Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 68, No. 65/Friday, April 4, 2003/Notices

16548 Federal Register / Vol. 68, No. 65 / Friday, April 4, 2003 / Notices The segregative effect associated with Statement, but was included and the National Park Service (NPS) the application terminated March 19, analyzed, along with 4 additional acquiring the land on which the lake 2000, in accordance with the notice alternatives, in the Final Supplemental sits. The lake was built by Sifford to published as FR Doc. 00–3267 in the Environmental Impact Statement. The provide scenic benefits and recreational Federal Register (65 FR 7057–8) dated full range of foreseeable environmental opportunities to guests at the nearby February 11, 2000. consequences was assessed, and Drakesbad Guest Ranch, which Sifford Dated: January 21, 2003. appropriate mitigating measures were owned. Drakesbad Guest Ranch is over Howard A. Lemm, identified. 100 years old and is still in operation to The Record of Decision includes a this day. It is owned by the National Acting Deputy State Director, Division of statement of the decision made, Resources. Park Service and is located within the synopses of other alternatives boundaries of Lassen Volcanic National [FR Doc. 03–8170 Filed 4–3–03; 8:45 am] considered, the basis for the decision, a Park. Drakesbad is operated by the BILLING CODE 4310–$$–P description of the environmentally Park’s concessioner, California Guest preferable alternative, a finding Services. Drakesbad, with nearby Dream DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR regarding impairment of park resources Lake, is a popular destination and has and values, a listing of measures to been visited by many generations of National Park Service minimize environmental harm, an families. -

Sierra Nevada Framework FEIS Chapter 3

table of contrents Sierra Nevada Forest Plan Amendment – Part 4.6 4.6. Vascular Plants, Bryophytes, and Fungi4.6. Fungi Introduction Part 3.1 of this chapter describes landscape-scale vegetation patterns. Part 3.2 describes the vegetative structure, function, and composition of old forest ecosystems, while Part 3.3 describes hardwood ecosystems and Part 3.4 describes aquatic, riparian, and meadow ecosystems. This part focuses on botanical diversity in the Sierra Nevada, beginning with an overview of botanical resources and then presenting a more detailed analysis of the rarest elements of the flora, the threatened, endangered, and sensitive (TES) plants. The bryophytes (mosses and liverworts), lichens, and fungi of the Sierra have been little studied in comparison to the vascular flora. In the Pacific Northwest, studies of these groups have received increased attention due to the President’s Northwest Forest Plan. New and valuable scientific data is being revealed, some of which may apply to species in the Sierra Nevada. This section presents an overview of the vascular plant flora, followed by summaries of what is generally known about bryophytes, lichens, and fungi in the Sierra Nevada. Environmental Consequences of the alternatives are only analyzed for the Threatened, Endangered, and Sensitive plants, which include vascular plants, several bryophytes, and one species of lichen. 4.6.1. Vascular plants4.6.1. plants The diversity of topography, geology, and elevation in the Sierra Nevada combine to create a remarkably diverse flora (see Section 3.1 for an overview of landscape patterns and vegetation dynamics in the Sierra Nevada). More than half of the approximately 5,000 native vascular plant species in California occur in the Sierra Nevada, despite the fact that the range contains less than 20 percent of the state’s land base (Shevock 1996). -

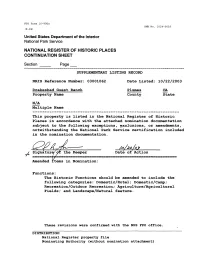

Drakesbad Guest Ranch Plumas CA Property Name County State

NFS Form 10-900a OMB No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES CONTINUATION SHEET Section Page SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 03001062 Date Listed: 10/22/2003 Drakesbad Guest Ranch Plumas CA Property Name County State N/A Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. / Signatur the Keeper Date of Action Amended Items in Nomination: Functions: The Historic Functions should be amended to include the following categories: Domestic/Hotel; Domestic/Camp; Recreation/Outdoor Recreation; Agriculture/Agricultural Fields; and Landscape/Natural feature. These revisions were confirmed with the NFS FPO office. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NPS Form 1 0-900 OMB No. 1 024-001 8 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior , National Park Service \(} v> NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Drakesbad Guest Ranch other name/site number: Drake's Baths; Drakesbad Resort; Hot Springs Valley 2. Location street & number: N/A not for publication: n/a vicinity: Head of Warner Creek Valley, Lassen Volcanic National Park city /town: Chester state: California code: CA county: Plumas code: 063 zip code: 96020 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professionjiiemiirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study

14 Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study The Visitor Services Project 14 OMB Approval 1024-0224 Expiration Date: 02/29/2000 United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Lassen Volcanic National Park P.O. Box 100 Mineral, CA 96020 Dear Visitor: Thank you for participating in this important study. Our goal is to learn about the expectations, opinions, and interests of visitors to Lassen Volcanic National Park. This will assist us in our efforts to better manage this site and to serve you, the visitor. This questionnaire is only being given to a select number of visitors, so your participation is very important! It should only take a few minutes during or after your visit. When your visit is over, please complete the questionnaire. Seal it with the sticker provided on the last page and drop it in any U.S. mailbox. If you have any questions, please contact Margaret Littlejohn, VSP Coordinator, Cooperative Park Studies Unit, College of Forestry, Wildlife and Range Sciences, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho 83844-1133. We appreciate your help. Sincerely, /s/ Marilyn H. Parris Superintendent 14 DIRECTIONS One adult in your group should complete the questionnaire. It should only take a few minutes. When you have completed the questionnaire, please seal it with the sticker provided and drop it in any U.S. mailbox. We appreciate your help. PRIVACY ACT and PAPERWORK REDUCTION ACT statement: 16 U.S.C. 1a-7 authorizes collection of this information. This information will be used by park managers to better serve the public. Response to this request is voluntary. -

Hallelujah Junction Wildlife Area Land Management Plan

Hallelujah Junction Wildlife Area Land Management Plan PREPARED BY SUSTAIN ENVIRONMENTAL INC FOR THE California Department of Fish and Game North Central Region December 2009 SUSTAINABLE FORESTRY INITIATIVE rptfic'iii Printed on sustainable paper products COVER: Appleton Utopia Forest Stewardship Council certified by Smartwood (a Rainforest Alliance program), ISO 14001 Registered Environmental Management System, EPA SmartWay Transport Partner Interior pages: Navigator Hybrid 85%-100% recycled post consumer waste blended with virgin fiber, Forest Stewarship Council certified chain of custody, ISO 14001 Registered Environmental Management System, 80% energy from renewable resources Divider pages (main body): Domtar Colors Sustainable Forest Initiative fiber sourcing certified, 30% post consumer waste Divider pages (appendices): Hammermill Fore MP 30% post consumer waste PDF VERSION DESIGNED FOR DUPLEX PRINTING State of California The Resources Agency DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME Hallelujah Junction Wildlife Area Land Management Plan Sierra and Lassen Counties, California UPDATED: DECEMBER 2009 PREPARED FOR: California Department of Fish and Game North Central Region Headquarters 1701 Nimbus Road, Suite A Rancho Cordova, California 95670 Attention: Terri Weist 530.644.5980 PREPARED BY: Sustain Environmental Inc. 3104 "O" Street #164 Sacramento, California 95816 916.457.1856 APPRnvFn RY- Hallelujah Junction Wildlife Area Land Management Plan Table of Contents................................................................................................................................................i -

Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study

U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Social Science Program Visitor Services Project Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study [Insert image here] OMB Control Number:1024-0224 Current Expiration Date: 8/31/2014 2 Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Lassen Volcanic National Park P.O. Box 100 Mineral, CA 96063 IN REPLY REFER TO: January/June 2012 Dear Visitor: Thank you for participating in this study. Our goal is to learn about the expectations, opinions, and interests of visitors to Lassen Volcanic National Park. This information will assist us in our efforts to better manage this park and to serve you. This questionnaire is only being given to a select number of visitors, so your participation is very important! It should only take about 20 minutes to complete. Please complete this questionnaire. Seal it in and return it to us in the postage paid envelope provided. If you have any questions, please contact Margaret Littlejohn, NPS VSP Director, Park Studies Unit, College of Natural Resources, P.O. Box 441139, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho 83844-1139, phone: 208-885-7863, email: [email protected]. We appreciate your help. Sincerely, Darlene M. Koontz Superintendent Lassen Volcanic National Park Visitor Study 3 DIRECTIONS At the end of your visit: 1. Please have the selected individual (at least 16 years old) complete this questionnaire. 2. Answer the questions carefully since each question is different. 3. For questions that use circles (O), please mark your answer by filling in the circle with black or blue ink. -

Cultural Resources Overview of the Heinz Ranch, South Parcel (Approximately 1378 Acres) for the Stone Gate Master Planned Community, Washoe County, Nevada

Cultural Resources Overview of the Heinz Ranch, South Parcel (approximately 1378 acres) for the Stone Gate Master Planned Community, Washoe County, Nevada Project Number: 2016-110-1 Submitted to: Heinz Ranch Company, LLCt 2999 Oak Road, Suite 400 Walnut Creek, CA 94597 Prepared by: Michael Drews Dayna Giambastiani, MA, RPA Great Basin Consulting Group, LLC. 200 Winters Drive Carson City, Nevada 89703 July7, 2016 G-1 Summary Heinz Ranch was established in 1855 by Frank Heinz, an emigrant from Germany, who together with his wife Wilhelmina, turned it into a profitable cow and calf operation (Nevada Department of Agriculture 2016). In 2004, Heinz Ranch received the Nevada Centennial Ranch and Farm award from the Nevada Department of Agriculture for being an active ranch for over 100 years. A Class II archaeological investigation of the property was conducted in May and June 2016. Several prehistoric archaeological sites have been recorded on the property. Habitation sites hold the potential for additional research and have previously been determined eligible to the National Register of Historic Places. Historic sites relating to mining and transportation along with the ranching landscape are also prominent. Architectural resources on the property consist of several barns, outbuildings and residences. The barns are notable for their method of construction. Many are constructed of hand hewn posts and beams, and assembled with pegged mortise and tenon joinery. They date to the earliest use of the ranch. Residences generally date to the 1930s. Historic sites and resources located on Heinz Ranch provide an opportunity for more scholarly research into the prehistory and history of Cold Springs Valley (also Laughton’s Valley) and the region in general. -

HISTORY of WASHOE COUNTY Introduction

HISTORY OF WASHOE COUNTY Introduction Lying in the northwest portion of the State of Nevada, named for a tribe of American Indians and containing a land area in excess of 6,000 square miles, Washoe County today consists of two of the nine original counties -- Washoe and Lake (later renamed Roop) Counties -- into which the Territory of Nevada was divided by the first territorial legislature in 1861. The country, "a land of contrasts, extremes, and apparent contradictions, of mingled barrenness and fertility, beauty and desolation, aridity and storm,"1 was claimed by the Spanish Empire until 1822 when it became a part of Mexican territory resulting from Mexico's successful war of independence from Spain. Mexico ceded the area to the United States in 1848 following the Mexican War, and the ceded lands remained part of the "unorganized territory" of the United States until 1850. Spanish and Mexican constructive possession probably had little effect on the life styles of the Northern Paiutes and the Washos -- the two American Indian tribes which inhabited the area. The Northern Paiutes ranged over most of Washoe County2 save the series of valleys lying along the eastern foothills of the Sierra Nevada. These valleys were the domain of the Washos, a small, nomadic tribe whose members spoke an alien tongue and from which the name of the county is derived3. The 1840's During the 1840's Washoe County was traversed by a number of trappers and explorers, as well as several well-defined emigrant trails leading to California and Oregon. In 1843 mountain man "Old Bill" Williams4 led his trappers from the Klamath Lake region of California to Pyramid Lake and the Truckee River. -

Chronology of Emplacement of Mesozoic Batholithic Complexes in California and Western Nevada by J

Chronology of Emplacement of Mesozoic Batholithic Complexes In California and Western Nevada By J. F. EVERNDEN and R. W. KISTLER GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 623 Prepared in cooperation with the University of California (Berkeley) Department of Geological Sciences UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1970 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WALTER J. HICKEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director Library of Con;gress CSJtalog-card No. 7s-.60.38'60 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $1.25 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract-------------------------------~---------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 Introduction--------------------------------------------------------------------------------~----------------- 1 Analyt:cal problems ____________________ -._______________________________________________________________________ 2 Analytical procedures______________________________________________________________________________________ 2 Precision and accuracy ___________________ -.- __ _ _ _ _ __ _ _ _ __ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 2 Potassium determinations_______________________________________________________________________________ · 2 Argon determinations--------~------------------~------------------------------------------------------ 5 Chemical and crystallographic effects on potassium-argon ages----------.----------------------------------------- -

The Beckwourth Emigrant Trail: Using Historical Accounts to Guide Archaeological Fieldwork in the Plumas National Forest

THE BECKWOURTH EMIGRANT TRAIL: USING HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS TO GUIDE ARCHAEOLOGICAL FIELDWORK IN THE PLUMAS NATIONAL FOREST ANGEL MORGAN LASSEN NATIONAL FOREST, ALMANOR RANGER DISTRICT KAREN MITCHELL PLUMAS NATIONAL FOREST, FEATHER RIVER RANGER DISTRICT The Beckwourth Emigrant Trail Project was created by the Forest Service for the purpose of composing a detailed and comprehensive site record that was done by archaeologists. In 1851, James Beckwourth built the wagon road to accommodate travelers in search of gold. It ran from Sparks, Nevada to Bidwell’s Bar, California. Historical General Land Office (GLO) maps and survey notes were used in conjunction with Andrew Hammond’s field maps to identify trail segments. The segments were located and compared with historialc documentation of the trail’s route. This paper will juxtapose the approximate location of the trail according to the historical documentation with the segments located in the field, categorized according to Oregon-California Trails Association (OCTA) standards for trail classification. From 1851 to 1855 the Beckwourth Emigrant Trail was the favored route for those seeking their fortune in the California gold rush. The wagon trail proved effective in getting these travelers over the Sierra Nevada mountain pass and into gold country, despite its extremely difficult route. When the railroad displaced the wagon routes into California, the trail fell into disuse. In 2009, Forest Service archaeologists from the Feather River Ranger District, in partnership with Mt. Hough Ranger District in Plumas National Forest planned to use historical accounts and maps to locate and record existing segments of the trail, beginning the first formal recordation of the Beckwourth Emigrant Trail. -

USGS Topographic Maps of California

USGS Topographic Maps of California: 7.5' (1:24,000) Planimetric Planimetric Map Name Reference Regular Replace Ref Replace Reg County Orthophotoquad DRG Digital Stock No Paper Overlay Aberdeen 1985, 1994 1985 (3), 1994 (3) Fresno, Inyo 1994 TCA3252 Academy 1947, 1964 (pp), 1964, 1947, 1964 (3) 1964 1964 c.1, 2, 3 Fresno 1964 TCA0002 1978 Ackerson Mountain 1990, 1992 1992 (2) Mariposa, Tuolumne 1992 TCA3473 Acolita 1953, 1992, 1998 1953 (3), 1992 (2) Imperial 1992 TCA0004 Acorn Hollow 1985 Tehama 1985 TCA3327 Acton 1959, 1974 (pp), 1974 1959 (3), 1974 (2), 1994 1974 1994 c.2 Los Angeles 1994 TCA0006 (2), 1994, 1995 (2) Adelaida 1948 (pp), 1948, 1978 1948 (3), 1978 1948, 1978 1948 (pp) c.1 San Luis Obispo 1978 TCA0009 (pp), 1978 Adelanto 1956, 1968 (pp), 1968, 1956 (3), 1968 (3), 1980 1968, 1980 San Bernardino 1993 TCA0010 1980 (pp), 1980 (2), (2) 1993 Adin 1990 Lassen, Modoc 1990 TCA3474 Adin Pass 1990, 1993 1993 (2) Modoc 1993 TCA3475 Adobe Mountain 1955, 1968 (pp), 1968 1955 (3), 1968 (2), 1992 1968 Los Angeles, San 1968 TCA0012 Bernardino Aetna Springs 1958 (pp), 1958, 1981 1958 (3), 1981 (2) 1958, 1981 1981 (pp) c.1 Lake, Napa 1992 TCA0013 (pp), 1981, 1992, 1998 Agua Caliente Springs 1959 (pp), 1959, 1997 1959 (2) 1959 San Diego 1959 TCA0014 Agua Dulce 1960 (pp), 1960, 1974, 1960 (3), 1974 (3), 1994 1960 Los Angeles 1994 TCA0015 1988, 1994, 1995 (3) Aguanga 1954, 1971 (pp), 1971, 1954 (2), 1971 (3), 1982 1971 1954 c.2 Riverside, San Diego 1988 TCA0016 1982, 1988, 1997 (3), 1988 Ah Pah Ridge 1983, 1997 1983 Del Norte, Humboldt 1983 -

P Cell N Walkerlane

FRIENDS OF THE PLEISTOCENE PACIFIC CELL FIELD TRIP NORTHERN WALKER LANE AND NORTHEAST SIERRA NEVADA October 12-14, 2001. Contributors: Ken Adams1, Rich Briggs2, Bill Bull3, Jim Brune4, Darryl Granger5, Alan Ramelli6, Clifford Riebe7, Tom Sawyer8, John Wakabayashi9, Chris Wills10 1Desert Research Institute, Reno, Nevada, [email protected] 2Center for Neotectonic Studies, University of Nevada, Reno, NV 89557, [email protected] 3Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, [email protected] 4Seismology Laboratory 714, University of Nevada, Reno NV 89557, [email protected] 5Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences & PRIME Lab, Purdue University, West Lafeyette, IN 47907, [email protected] 6Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, MS 178, University of Nevada, Reno, NV 89557, [email protected] 7Department of Earth and Planetary Science, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, [email protected] 8Piedmont Geosciences, Inc., 10235 Blackhawk Dr., Reno, NV 89506, [email protected] 91329 Sheridan Lane, Hayward, CA 94544, [email protected], http://www.tdl.com/~wako/ 10California Division of Mines and Geology,185 Berry St Suite 210, San Francisco CA 94107, [email protected] SPECIAL THANKS TO: Friends of the Pleistocene Pacific Cell website manager, Doug La Farge ([email protected]), for managing the Pacific Cell website (http://pacific.pleistocene.org/), including facilitating production of online field trip guides, and coordination of group emails. Special thanks also to the Ramelli family, for allowing our trip to use their property as the meeting place. INTRODUCTION John Wakabayashi, 1329 Sheridan Lane, Hayward, CA 94544; [email protected] This field trip examines stops related to the neotectonics, paleoseismology, and evolution of the northern Walker Lane, as well as general controls on erosion rates, and topographic evolution of the Sierra Nevada.