Stitching a River Culture: Trade, Communication and Transportation to 1960

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

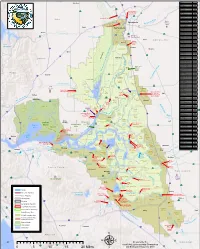

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-Creation of the Tribal Identity On

From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-creation of the Tribal Identity on the Tule River Indian Reservation in California from Euroamerican Contact to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 By Kumiko Noguchi B.A. (University of the Sacred Heart) 2000 M.A. (Rikkyo University) 2003 Dissertation Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Native American Studies in the Office of Graduate Studies of the University of California Davis Approved Steven J. Crum Edward Valandra Jack D. Forbes Committee in Charge 2009 i UMI Number: 3385709 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3385709 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Kumiko Noguchi September, 2009 Native American Studies From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-creation of the Tribal Identity on the Tule River Indian Reservation in California from Euroamerican contact to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 Abstract The main purpose of this study is to show the path of tribal development on the Tule River Reservation from 1776 to 1936. It ends with the year of 1936 when the Tule River Reservation reorganized its tribal government pursuant to the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. -

Sacramento Historic Trails

Sacramento Historic Trail Hike And Sacramento Historic R. R. Trail Hike 1 Sacramento Historic Hike How to take the hike 1) Railroad Museum (requires admission fee, save ticket stubs) 2) Sacramento History Museum 3) Big Four Building. From the RR Museum, exit to the right. Big Four Building is located and the RR Library and the Hardware store is located within. 4) The earliest Sacramento, a tent city. 5) Central Pacific RR Passenger Station 6) Eagle Theatre. Across the street from the CPRP Station 7) Cobblestone Streets 8) The Globe and the Delta King. 9) Pony Express Rider statue. NE Corner of 2nd and J 10) Sacramento Southern RR. From Front Street, go up K. St. to see the Lady Adams Building. Return to Front St. and you can go to the Visitor’s Center. Continue on Front St. to the Old Schoolhouse Museum on the SW corner of Front and L Streets. 11) Hike down K Street past the Convention Center to the State Indian Museum. Go to L Street to Sutter’s Fort. 12) From Sutter’s Fort, hike down L Street over to the State Capitol and take a self-guided tour. 13) From the State Capitol, hike down Capitol Avenue to 9th Street and head south to N Street. Visit Stanford House (Currently closed for renovations) 14) From Stanford House, head west on N Street and turn left on 3rd Street to Crocker Art Gallery. 2 15) From the Crocker Art Gallery, hike to SVRR Station and then back to Old Town. 16) Head back up Front Street and under Capitol to Old Town. -

BORDENTOWN to ROEBLING VIA the RIVERLINE the Tracks for The

BORDENTOWN TO ROEBLING VIA THE RIVERLINE The tracks for the light rail train you are riding on were laid upon the right of way of the Camden & Amboy Railway Company, chartered in 1830 along with the Delaware & Raritan Canal Company (known as the “Joint Companies”) and laid in the1830s between Camden and Amboy. Both railroad and canal officially opened in 1834, but sections of the railroad were in service for freight in1833 with horse-drawn cars. Tied together and pulled by steam tugs, canalboats carrying coal from the Lehigh and Schuylkill Valleys would cross the river from Pennsylvania’s Delaware Canal. A cable ferry (1848-1912) and outlet locks at Lam- bertville and New Hope made the trip from the Lehigh Valley to Trenton much shorter, via the Feeder of the D & R. Schuylkill Valley coal continued to cross the river from Philadelphia and Bristol, entering the D&R at the Bor- dentown Lock (#1) at the mouth of Crosswicks Creek. What to look for Crosswicks Creek where it flows into the Delaware River Bluffs on the left on which Bordentown was built and the narrow strip of land under the bluffs where this train is traveling. Bordentown City is bordered on the south by Black’s Creek. Slips in the river shoreline on the lee side of Newbold Island where canalboats from Pennsylvania transferred their cargo (coal) to waiting trains or waited for entrance into Lock #1. Abandoned canalboats in the channel between Newbold Island and the shore, preserved because they are always wet. We have planned this trip for low tide so they can be seen. -

BC Ferry Services Inc. Accessibility Advisory Committee Meeting Minutes

BC Ferry Services Inc. Accessibility Advisory Committee Meeting Minutes Meeting Details Date July 23, 2014 Time 1:00 pm – 4:00 pm Location: BC Ferries Head Office – Suite 500-1621 Blanshard Street Attendance Public Interest Representatives Pat Danforth, Board Member, BC Coalition of People with Disabilities Susan Gallagher, Alliance for Equality of Blind Canadians Hugh Mitchell, Canadian Hard of Hearing Association Scott Heron, Co-Chair, Spinal Cord Injury BC Jane Sheaff, Seniors Serving Seniors Ernie Stignant, Disability Resource Centre/MSI Mary K. Kennedy, CNIB Marnie Essery, Inter-municipal Advisory Committee on Disability Issues Les Chan, Disability Resource Centre Barbara Schuster, CNIB BC Ferries Representatives Karen Tindall, Director of Customer Care, Customer Care Department Garnet Renning, Customer Service & Sales Representative Stephen Nussbaum, Regional Manager, Swartz Bay David Carroll, Director, Terminal Construction, Engineering Darin Guenette, Manager, Public Affairs Bruce Paterson, Fleet Technical Director, Engineering Sheila O’Neill, Catering Superintendent, Central Coast Captain Chris Frappell, Marine Superintendent, South and Central Coast Guests Jeffrey Li, Project Manager Joanne Doyle, Manager, Master Planning Elisabeth Broadley, Customer Relations Advisor, Customer Care Regrets Valerie Thoem, Independent Steve Shardlow, Training Manager, Terminals Jeff Davidson, Director, Retail Services, Food and Retail Operations 1 | P a g e Introductions Co-Chairs Scott Heron and Karen Tindall welcomed the members of the committee Review of Minutes – February 4, 2014 Karen Tindall reported on Action Items from last meeting Note: July 23 was Ernie Stignant’s last meeting – Les Chan will be representing the Disability Resource Centre Standing Items Loading Practices Stephen Nussbaum went through six months’ worth of customer comments looking for trends in comments from persons with disabilities. -

Suisun Marsh Protection Plan Map (PDF)

Proposed County Parks (Hill Slough, Fairfield Beldon’s Landing) Develop passive recreation facilities compatible with Marsh protection (e.g. fishing, picnicking, hiking, nature study.) Boat launching ramp may be constructed Suis nu at Beldon’s Landing. City Suisun Marsh 8 0 etaterstnI 80 a Protection Plan Map flHighway 12 San Francisco Bay Conservation (6) b .J ' and Development Commission I Denverton (7) I December 1976 ) I ~4 Slough Thomasson Shiloh Primary Management Area danyor, Potrero Hills ':__. .---) ... .. ... ~ . _,,. - (8) Secondary Management Area ~ ,. .,,,, Denverton ,,a !\.:r ~ Water-Related Industry Reserve Area c Beldon’s BRADMOOR ISLAND Slough (5) Landing t +{larl!✓' Road Boundary of Wildlife Areas and (9) Ecological Reserves Little I Honker (1) Grizzly Island Unit (9) Bay (2) Crescent Unit (4) Montezuma Slough (3) Island Slough Unit JOICE ISLAND (3) r (4) Joice Island Unit (5) Rush Ranch National Estuarine (10) Ecological Reserve Kirby Hill (6) Hill Slough Wildlife Area Suisun (7) Peytonia Slough Ecological Reserve (8) Grey Goose Unit GRIZZLY ISLAND (2) GRIZZLY ISLAND (9) Gold Hills Unit (10) Garibaldi Unit (11) West Family Unit (12) Goodyear Slough Unit Benicia Area Recommended for Aquisition a. Lawler Property I (11) Hills b. Bryan Property . ~-/--,~ c. Smith Property ,,-:. ...__.. ,, \ 1 Collinsville: Reserve seasonal marshes and Benicia Hills lowland grasslands for their Amended 2011 Grizzly Bay intrinsic value to marsh wildlife and Steep slopes with high landslide and soil to act as the buffer between the erosion potentials. Active fault location. Land (1) Marsh and any future water-related Collinsville Road use practices should be controlled to prevent uses to the east. -

Sierra Nevada Framework FEIS Chapter 3

table of contrents Sierra Nevada Forest Plan Amendment – Part 4.6 4.6. Vascular Plants, Bryophytes, and Fungi4.6. Fungi Introduction Part 3.1 of this chapter describes landscape-scale vegetation patterns. Part 3.2 describes the vegetative structure, function, and composition of old forest ecosystems, while Part 3.3 describes hardwood ecosystems and Part 3.4 describes aquatic, riparian, and meadow ecosystems. This part focuses on botanical diversity in the Sierra Nevada, beginning with an overview of botanical resources and then presenting a more detailed analysis of the rarest elements of the flora, the threatened, endangered, and sensitive (TES) plants. The bryophytes (mosses and liverworts), lichens, and fungi of the Sierra have been little studied in comparison to the vascular flora. In the Pacific Northwest, studies of these groups have received increased attention due to the President’s Northwest Forest Plan. New and valuable scientific data is being revealed, some of which may apply to species in the Sierra Nevada. This section presents an overview of the vascular plant flora, followed by summaries of what is generally known about bryophytes, lichens, and fungi in the Sierra Nevada. Environmental Consequences of the alternatives are only analyzed for the Threatened, Endangered, and Sensitive plants, which include vascular plants, several bryophytes, and one species of lichen. 4.6.1. Vascular plants4.6.1. plants The diversity of topography, geology, and elevation in the Sierra Nevada combine to create a remarkably diverse flora (see Section 3.1 for an overview of landscape patterns and vegetation dynamics in the Sierra Nevada). More than half of the approximately 5,000 native vascular plant species in California occur in the Sierra Nevada, despite the fact that the range contains less than 20 percent of the state’s land base (Shevock 1996). -

A Strategic Plan for Improving Water-Based

A STRATEGIC PLAN FOR IMPROVING WATER-BASED TOURISM IN OREGON’S MT HOOD TERRITORY submitted to The Destination Marketing Organization for Clackamas County 150 Beavercreek Rd, Oregon City, OR www.mthoodterritory.com submitted by TH MARCH 20 2018 STRATEGIC PLAN FOR WATER-BASED TOURISM IN OREGON’S MT HOOD TERRITORY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1-1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Water is fun. Nearly everyone has experienced the pleasure of a refreshing dip on a hot summer day, the mist of a waterfall, or the thrill of a cliff jump. Some seek solitude by the edge of a lonely stream, others find excitement in extreme whitewater. Youth splash, teens jump, adults wade, but we all look to water for reprieve from our daily routine. Water recreation gives us a chance to see life differently. We test our skills with a fishing rod or a paddle, we relax on a float, and we use water as a medium to gather family and friends. Oregon’s recreational waters are visited 80 million times annually by people looking to swim, fish, surf, sail, paddle or simply sit by the beach. It seems that water is not only essential to life, but to our happiness. People migrate towards water for fun and Clackamas County has a lot of it. Mt Hood Territory, Clackamas County’s tourism marketing organization, initiated this comprehensive study to determine if its water recreation assets are being used to their greatest economic potential. Are the county’s rivers and lakes attracting visitors and maximizing their enjoyment? Are they being managed and marketed in a sustainable manner to increase water-based recreation? Do they generate overnight stays without degrading the environment or the experience? To answer these questions, the county hired Crane Associates of Burlington Vermont, a consulting firm with 20 years of international and domestic experience in environmental economics and sustainable economic development with a specialty in water-based recreation. -

Genealogical Sketch Of

Genealogy and Historical Notes of Spamer and Smith Families of Maryland Appendix 2. SSeelleecctteedd CCoollllaatteerraall GGeenneeaallooggiieess ffoorr SSttrroonnggllyy CCrroossss--ccoonnnneecctteedd aanndd HHiissttoorriiccaall FFaammiillyy GGrroouuppss WWiitthhiinn tthhee EExxtteennddeedd SSmmiitthh FFaammiillyy Bayard Bache Cadwalader Carroll Chew Coursey Dallas Darnall Emory Foulke Franklin Hodge Hollyday Lloyd McCall Patrick Powel Tilghman Wright NEW EDITION Containing Additions & Corrections to June 2011 and with Illustrations Earle E. Spamer 2008 / 2011 Selected Strongly Cross-connected Collateral Genealogies of the Smith Family Note The “New Edition” includes hyperlinks embedded in boxes throughout the main genealogy. They will, when clicked in the computer’s web-browser environment, automatically redirect the user to the pertinent additions, emendations and corrections that are compiled in the separate “Additions and Corrections” section. Boxed alerts look like this: Also see Additions & Corrections [In the event that the PDF hyperlink has become inoperative or misdirects, refer to the appropriate page number as listed in the Additions and Corrections section.] The “Additions and Corrections” document is appended to the end of the main text herein and is separately paginated using Roman numerals. With a web browser on the user’s computer the hyperlinks are “live”; the user may switch back and forth between the main text and pertinent additions, corrections, or emendations. Each part of the genealogy (Parts I and II, and Appendices 1 and 2) has its own “Additions and Corrections” section. The main text of the New Edition is exactly identical to the original edition of 2008; content and pagination are not changed. The difference is the presence of the boxed “Additions and Corrections” alerts, which are superimposed on the page and do not affect text layout or pagination. -

ARCTIC Exploration the SEARCH for FRANKLIN

CATALOGUE THREE HUNDRED TWENTY-EIGHT ARCTIC EXPLORATION & THE SeaRCH FOR FRANKLIN WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is devoted to Arctic exploration, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the later search for Sir John Franklin. It features many volumes from a distinguished private collection recently purchased by us, and only a few of the items here have appeared in previous catalogues. Notable works are the famous Drage account of 1749, many of the works of naturalist/explorer Sir John Richardson, many of the accounts of Franklin search expeditions from the 1850s, a lovely set of Parry’s voyages, a large number of the Admiralty “Blue Books” related to the search for Franklin, and many other classic narratives. This is one of 75 copies of this catalogue specially printed in color. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues: 320 Manuscripts & Archives, 322 Forty Years a Bookseller, 323 For Readers of All Ages: Recent Acquisitions in Americana, 324 American Military History, 326 Travellers & the American Scene, and 327 World Travel & Voyages; Bulletins 36 American Views & Cartography, 37 Flat: Single Sig- nificant Sheets, 38 Images of the American West, and 39 Manuscripts; e-lists (only available on our website) The Annex Flat Files: An Illustrated Americana Miscellany, Here a Map, There a Map, Everywhere a Map..., and Original Works of Art, and many more topical lists. Some of our catalogues, as well as some recent topical lists, are now posted on the internet at www.reeseco.com. -

UC Davis San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science

UC Davis San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science Title Implications for Greenhouse Gas Emission Reductions and Economics of a Changing Agricultural Mosaic in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/99z2z7hb Journal San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science, 15(3) ISSN 1546-2366 Authors Deverel, Steven Jacobs, Paul Lucero, Christina et al. Publication Date 2017 DOI 10.15447/sfews.2017v15iss3art2 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California SEPTEMBER 2017 RESEARCH Implications for Greenhouse Gas Emission Reductions and Economics of a Changing Agricultural Mosaic in the Sacramento – San Joaquin Delta Steven Deverel1, Paul Jacobs2, Christina Lucero1, Sabina Dore1, and T. Rodd Kelsey3 profit changes relative to the status quo. We spatially Volume 15, Issue 3 | Article 2 https://doi.org/10.15447/sfews.2017v15iss3art2 assigned areas for rice and wetlands, and then allowed the Delta Agricultural Production (DAP) * Corresponding author: [email protected] model to optimize the allocation of other crops to 1 HydroFocus, Inc. maximize profit. The scenario that included wetlands 2827 Spafford Street, Davis, CA 95618 USA decreased profits 79% relative to the status quo but 2 University of California, Davis -1 One Shields Ave, Davis, CA 95616 USA reduced GHG emissions by 43,000 t CO2-e yr (57% 3 The Nature Conservancy reduction). When mixtures of rice and wetlands were 555 Capitol Mall Suite 1290, Sacramento, CA 95814 USA introduced, farm profits decreased 16%, and the GHG -1 emission reduction was 33,000 t CO2-e yr (44% reduction).