Exercise 6.1 I. 1. Inappropriate Appeal to Authority (Irrelevant Authority) 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center Ad hominem (Argument to the person): Attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. We would take her position on child abuse more seriously if she weren’t so rude to the press. Ad populum appeal (appeal to the public): Draws on whatever people value such as nationality, religion, family. A vote for Joe Smith is a vote for the flag. Alleged certainty: Presents something as certain that is open to debate. Everyone knows that… Obviously, It is obvious that… Clearly, It is common knowledge that… Certainly, Ambiguity and equivocation: Statements that can be interpreted in more than one way. Q: Is she doing a good job? A: She is performing as expected. Appeal to fear: Uses scare tactics instead of legitimate evidence. Anyone who stages a protest against the government must be a terrorist; therefore, we must outlaw protests. Appeal to ignorance: Tries to make an incorrect argument based on the claim never having been proven false. Because no one has proven that food X does not cause cancer, we can assume that it is safe. Appeal to pity: Attempts to arouse sympathy rather than persuade with substantial evidence. He embezzled a million dollars, but his wife had just died and his child needed surgery. Begging the question/Circular Logic: Proof simply offers another version of the question itself. Wrestling is dangerous because it is unsafe. Card stacking: Ignores evidence from the one side while mounting evidence in favor of the other side. Users of hearty glue say that it works great! (What is missing: How many users? Great compared to what?) I should be allowed to go to the party because I did my math homework, I have a ride there and back, and it’s at my friend Jim’s house. -

35 Fallacies

THIRTY-TWO COMMON FALLACIES EXPLAINED L. VAN WARREN Introduction If you watch TV, engage in debate, logic, or politics you have encountered the fallacies of: Bandwagon – "Everybody is doing it". Ad Hominum – "Attack the person instead of the argument". Celebrity – "The person is famous, it must be true". If you have studied how magicians ply their trade, you may be familiar with: Sleight - The use of dexterity or cunning, esp. to deceive. Feint - Make a deceptive or distracting movement. Misdirection - To direct wrongly. Deception - To cause to believe what is not true; mislead. Fallacious systems of reasoning pervade marketing, advertising and sales. "Get Rich Quick", phone card & real estate scams, pyramid schemes, chain letters, the list goes on. Because fallacy is common, you might want to recognize them. There is no world as vulnerable to fallacy as the religious world. Because there is no direct measure of whether a statement is factual, best practices of reasoning are replaced be replaced by "logical drift". Those who are political or religious should be aware of their vulnerability to, and exportation of, fallacy. The film, "Roshomon", by the Japanese director Akira Kurisawa, is an excellent study in fallacy. List of Fallacies BLACK-AND-WHITE Classifying a middle point between extremes as one of the extremes. Example: "You are either a conservative or a liberal" AD BACULUM Using force to gain acceptance of the argument. Example: "Convert or Perish" AD HOMINEM Attacking the person instead of their argument. Example: "John is inferior, he has blue eyes" AD IGNORANTIAM Arguing something is true because it hasn't been proven false. -

The Acquisition of Scientific Knowledge Via Critical Thinking: a Philosophical Approach to Science Education

Forum on Public Policy The Acquisition of Scientific Knowledge via Critical Thinking: A Philosophical Approach to Science Education Dr. Isidoro Talavera, Philosophy Professor and Lead Faculty, Department of Humanities & Communication Arts, Franklin University, Ohio, USA. Abstract There is a gap between the facts learned in a science course and the higher-cognitive skills of analysis and evaluation necessary for students to secure scientific knowledge and scientific habits of mind. Teaching science is not just about how we do science (i.e., focusing on just accumulating undigested facts and scientific definitions and procedures), but why (i.e., focusing on helping students learn to think scientifically). So although select subject matter is important, the largest single contributor to understanding the nature and practice of science is not the factual content of the scientific discipline, but rather the ability of students to think, reason, and communicate critically about that content. This is achieved by a science education that helps students directly by encouraging them to analyze and evaluate all kinds of phenomena, scientific, pseudoscientific, and other. Accordingly, the focus of this treatise is on critical thinking as it may be applied to scientific claims to introduce the major themes, processes, and methods common to all scientific disciplines so that the student may develop an understanding about the nature and practice of science and develop an appreciation for the process by which we gain scientific knowledge. Furthermore, this philosophical approach to science education highlights the acquisition of scientific knowledge via critical thinking to foment a skeptical attitude in our students so that they do not relinquish their mental capacity to engage the world critically and ethically as informed and responsibly involved citizens.1 I. -

Informal Logic Examples and Exercises

Contents Section 1 Quotation Marks: Direct Quotes, Scare Quotes, Use/Mention Quotes 1 Introduction 1 Instructions 5 Exercises 7 Section 2 Meaning and Definition 13 Introduction 13 Instructions 17 Exercises 19 Section 3 Ambiguity, Homophony, Vagueness, Generality 23 Introduction 23 Instructions 27 Exercises 29 Section 4 Connotation and Assertive Content 35 Introduction 35 Instructions 37 Exercises 39 Section 5 Simple and Compound Sentences 45 Introduction 45 Instructions 49 Exercises 51 vi Contents Section 6 Arguments; Simple and Serial Argument Forms 61 Introduction 61 Instructions 65 Exercises 67 Section 7 Convergent, Divergent, and Linked Argument Forms 81 Introduction 81 Instructions 85 Exercises 87 Section 8 Unstated Premises and Conclusions; Extraneous Material 95 Introduction 95 Instructions 99 Exercises 10 1 Section 9 Complex Arguments 115 Introduction 115 Instructions 121 Exercises 123 Section 10 Argument Strengths 145 Introduction 145 Instructions 149 Exercises 151 Section 11 Valid Deductive Arguments: Propositional Logic 159 Introduction 159 Instructions 165 Exercises 167 Section 12 Valid Deductive Arguments: Quantificational Logic 179 Introduction 179 Instructions 187 Exercises 189 Contents vii Section 13 Fallacies One 199 Argument from Authority Two Wrongs Make a Right Irrelevant Reason Argument from Ignorance Ambiguous Argument Slippery Slope Argument from Force Introduction 199 Instructions for Sections 13-16 203 Exercises 205 Section 14 Fallacies Two 213 Ad Hominem Argument Provincialism Tokenism Hasty Conclusion Questionable -

False Dilemma Wikipedia Contents

False dilemma Wikipedia Contents 1 False dilemma 1 1.1 Examples ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Morton's fork ......................................... 1 1.1.2 False choice .......................................... 2 1.1.3 Black-and-white thinking ................................... 2 1.2 See also ................................................ 2 1.3 References ............................................... 3 1.4 External links ............................................. 3 2 Affirmative action 4 2.1 Origins ................................................. 4 2.2 Women ................................................ 4 2.3 Quotas ................................................. 5 2.4 National approaches .......................................... 5 2.4.1 Africa ............................................ 5 2.4.2 Asia .............................................. 7 2.4.3 Europe ............................................ 8 2.4.4 North America ........................................ 10 2.4.5 Oceania ............................................ 11 2.4.6 South America ........................................ 11 2.5 International organizations ...................................... 11 2.5.1 United Nations ........................................ 12 2.6 Support ................................................ 12 2.6.1 Polls .............................................. 12 2.7 Criticism ............................................... 12 2.7.1 Mismatching ......................................... 13 2.8 See also -

Some Common Fallacies of Argument Evading the Issue: You Avoid the Central Point of an Argument, Instead Drawing Attention to a Minor (Or Side) Issue

Some Common Fallacies of Argument Evading the Issue: You avoid the central point of an argument, instead drawing attention to a minor (or side) issue. ex. You've put through a proposal that will cut overall loan benefits for students and drastically raise interest rates, but then you focus on how the system will be set up to process loan applications for students more quickly. Ad hominem: Here you attack a person's character, physical appearance, or personal habits instead of addressing the central issues of an argument. You focus on the person's personality, rather than on his/her ideas, evidence, or arguments. This type of attack sometimes comes in the form of character assassination (especially in politics). You must be sure that character is, in fact, a relevant issue. ex. How can we elect John Smith as the new CEO of our department store when he has been through 4 messy divorces due to his infidelity? Ad populum: This type of argument uses illegitimate emotional appeal, drawing on people's emotions, prejudices, and stereotypes. The emotion evoked here is not supported by sufficient, reliable, and trustworthy sources. Ex. We shouldn't develop our shopping mall here in East Vancouver because there is a rather large immigrant population in the area. There will be too much loitering, shoplifting, crime, and drug use. Complex or Loaded Question: Offers only two options to answer a question that may require a more complex answer. Such questions are worded so that any answer will implicate an opponent. Ex. At what point did you stop cheating on your wife? Setting up a Straw Person: Here you address the weakest point of an opponent's argument, instead of focusing on a main issue. -

Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I

Essential Logic Ronald C. Pine Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I All effective propaganda must be confined to a few bare necessities and then must be expressed in a few stereotyped formulas. Adolf Hitler Until the habit of thinking is well formed, facing the situation to discover the facts requires an effort. For the mind tends to dislike what is unpleasant and so to sheer off from an adequate notice of that which is especially annoying. John Dewey, How We Think Introduction In everyday speech you may have heard someone refer to a commonly accepted belief as a fallacy. What is usually meant is that the belief is false, although widely accepted. In logic, a fallacy refers to logically weak argument appeal (not a belief or statement) that is widely used and successful. Here is our definition: A logical fallacy is an argument that is usually psychologically persuasive but logically weak. By this definition we mean that fallacious arguments work in getting many people to accept conclusions, that they make bad arguments appear good even though a little commonsense reflection will reveal that people ought not to accept the conclusions of these arguments as strongly supported. Although logicians distinguish between formal and informal fallacies, our focus in this chapter and the next one will be on traditional informal fallacies.1 For our purposes, we can think of these fallacies as "informal" because they are most often found in the everyday exchanges of ideas, such as newspaper editorials, letters to the editor, political speeches, advertisements, conversational disagreements between people in social networking sites and Internet discussion boards, and so on. -

The Big Lie” Feedback Responses

2016 Two More Chains Fall Issue “The Big Lie” Feedback Responses Do you agree or disagree Please elaborate on why you What’s the next step? How do we bring opposing with “The Big Lie” agree or disagree. views together? concepts? Why? 1. (Respondent selected “Other” for job position.) [No Input] Learn how to read wildfires. Agree. Underestimating potential leads to Based on “Personal Experience.” accidents. 2. Firefighter I have over 33 years’ experience working We need to discuss revising the entry level training programs to Agree. for All Risk Fire Departments in California include this information and focus more on the intent of the Fire Based on “Personal Experience.” including CAL FIRE. Qualified as DIVS, Orders (not just memorizing) what they really mean—and how to SOFR, STCR, FAL1 to name a few. mitigate risk to acceptable levels before we engage. Through this experience and studies I What happened to S-133 and S-134? Have these course been have long ago formed the following eliminated and if so why? opinions: With the risk management process, we seek to mitigate risk, but cannot always remove risk. Therefore, manage the risk and decide if the mitigations are acceptable before we engage. I also agree that there is a culture to memorize and recognize the Standard Fire Orders, but in practice the culture does not fully support following the orders or complying with the intent of the orders. With this type of culture, we often set ourselves up for the opportunity to experience catastrophic results. 1 Do you agree or disagree Please elaborate on why you What’s the next step? How do we bring opposing with “The Big Lie” agree or disagree. -

Chapter 5: Informal Fallacies II

Essential Logic Ronald C. Pine Chapter 5: Informal Fallacies II Reasoning is the best guide we have to the truth....Those who offer alternatives to reason are either mere hucksters, mere claimants to the throne, or there's a case to be made for them; and of course, that is an appeal to reason. Michael Scriven, Reasoning Why don’t you ever see a headline, “Psychic wins lottery”? Internet Joke News Item, June 16, 2010: A six story statue of Jesus in Monroe city, Ohio was struck by lightning and destroyed. An adult book store across the street was untouched. Introduction In the last chapter we examined one of the major causes of poor reasoning, getting off track and not focusing on the issues related to a conclusion. In our general discussion of arguments (Chapters 1-3), however, we saw that arguments can be weak in two other ways: 1. In deductive reasoning, arguments can be valid, but have false or questionable premises, or in both deductive and inductive reasoning, arguments may involve language tricks that mislead us into presuming evidence is being offered in the premises when it is not. 2. In weak inductive arguments, arguments can have true and relevant premises but those premises can be insufficient to justify a conclusion as a reliable guide to the future. Fallacies that use deductive valid reasoning, but have premises that are questionable or are unfair in some sense in the truth claims they make, we will call fallacies of questionable premise. As a subset of fallacies of questionable premise, fallacies that use tricks in the way the premises are presented, such that there is a danger of presuming evidence has been offered when it has not, we will call fallacies of presumption. -

PHI 106 Critical Thinking and Problem Solving Literacy/Critical Inquiry (L)

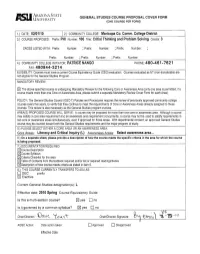

.'ARIZONA STATE IIrt GENERAL STUDIES COURSE PROPOSAL COVER FORM ~ UNIVERSITY (ONE COURSE PER FORM) 1.) DATE: 02101/10 I 2.) COMMUNITY COLLEGE: Maricopa Co. Comm. College District 3.) COURSE PROPOSED: Prefix: PHI Number: 106 Title: Critial Thinking and Problem Solving Credits: 3 CROSS LISTED WITH: Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: , Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: 4.) COMMUNITY COLLEGE INITIATOR: PATRICE NANGO PHONE: 480-461-7621 FAX: 480844-3214 ELIGIBILITY: Courses must have a current Course Equivalency Guide (CEG) evaluation. Courses evaluated as NT (non-transferable are not eligible for the General Studies Program. MANDATORY REVIEW: [gJ The above specified course is undergoing Mandatory Review for the following Core or Awareness Area (only one area is permitted; if a course meets more than one Core or Awareness Area, please submit a separate Mandatory Review Cover Form for each Area). POLICY: The General Studies Council (GSC-T) Policies and Procedures requires the review of previously approved community college courses every five years, to verify that they continue to meet the requirements of Core or Awareness Areas already assigned to these courses. This review is also necessary as the General Studies program evolves. AREA(S) PROPOSED COURSE WILL SERVE: A course may be proposed for more than one core or awareness area. Although a course may satisfy a core area requirement and an awareness area requirement concurrently, a course may not be used to satisfy requirements in two core or awareness areas simultaneously, even if approved for those areas. With departmental consent, an approved General Studies course may be counted toward both the General Studies requirements and the major program of study. -

I Correlative-Based Fallacies

Fallacies In Argument 本文内容均摘自 Wikipedia,由 ode@bdwm 编辑整理,请不要用于商业用途。 为方便阅读,删去了原文的 references,见谅 I Correlative-based fallacies False dilemma The informal fallacy of false dilemma (also called false dichotomy, the either-or fallacy, or bifurcation) involves a situation in which only two alternatives are considered, when in fact there are other options. Closely related are failing to consider a range of options and the tendency to think in extremes, called black-and-white thinking. Strictly speaking, the prefix "di" in "dilemma" means "two". When a list of more than two choices is offered, but there are other choices not mentioned, then the fallacy is called the fallacy of false choice. When a person really does have only two choices, as in the classic short story The Lady or the Tiger, then they are often said to be "on the horns of a dilemma". False dilemma can arise intentionally, when fallacy is used in an attempt to force a choice ("If you are not with us, you are against us.") But the fallacy can arise simply by accidental omission—possibly through a form of wishful thinking or ignorance—rather than by deliberate deception. When two alternatives are presented, they are often, though not always, two extreme points on some spectrum of possibilities. This can lend credence to the larger argument by giving the impression that the options are mutually exclusive, even though they need not be. Furthermore, the options are typically presented as being collectively exhaustive, in which case the fallacy can be overcome, or at least weakened, by considering other possibilities, or perhaps by considering a whole spectrum of possibilities, as in fuzzy logic. -

PHIL-1000: Critical Thinking 1

PHIL-1000: Critical Thinking 1 PHIL-1000: CRITICAL THINKING Cuyahoga Community College Viewing: PHIL-1000 : Critical Thinking Board of Trustees: 2018-05-24 Academic Term: Fall 2021 Subject Code PHIL - Philosophy Course Number: 1000 Title: Critical Thinking Catalog Description: This course serves as an introduction to principles of critical and creative thinking with an emphasis on real-world practical applications. Formal and informal tools of logical analysis will be applied to controversial topical issues. Credit Hour(s): 3 Lecture Hour(s): 3 Lab Hour(s): 0 Other Hour(s): 0 Requisites Prerequisite and Corequisite ENG-0995 Applied College Literacies, or appropriate score on English Placement Test. Note: ENG-0990 Language Fundamentals II taken prior to Fall 2021 will also meet prerequisite requirements. Outcomes Course Outcome(s): Acquire the tools of critical thinking for the deployment of skillful analysis, assessment and communication in the problem solving process. Essential Learning Outcome Mapping: Critical/Creative Thinking: Analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information in order to consider problems/ideas and transform them in innovative or imaginative ways. Objective(s): 1. Develop the paradigmatic characteristics of a critical thinker. 2. Recognize and discuss barriers to critical thinking caused by personal biases and by misuses of language. 3. List common types of meaning and definitions and apply them to rational arguments. 4. Determine the difference between reason and emotion and explain how that distinction impacts the ability to think critically. 5. Identify common errors that occur when evaluating knowledge and evidence. 6. Criticize arguments by applying the knowledge of various informal fallacies of ambiguity, relevance and unwarranted assumptions.