Florent Schmitt and the Lied Et Scherzo, Op

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DP Musée De La Libération UK.Indd

PRESS KIT LE MUSÉE DE LA LIBÉRATION DE PARIS MUSÉE DU GÉNÉRAL LECLERC MUSÉE JEAN MOULIN OPENING 25 AUGUST 2019 OPENING 25 AUGUST 2019 LE MUSÉE DE LA LIBÉRATION DE PARIS MUSÉE DU GÉNÉRAL LECLERC MUSÉE JEAN MOULIN The musée de la Libération de Paris – musée-Général Leclerc – musée Jean Moulin will be ofcially opened on 25 August 2019, marking the 75th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris. Entirely restored and newly laid out, the museum in the 14th arrondissement comprises the 18th-century Ledoux pavilions on Place Denfert-Rochereau and the adjacent 19th-century building. The aim is let the general public share three historic aspects of the Second World War: the heroic gures of Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque and Jean Moulin, and the liberation of the French capital. 2 Place Denfert-Rochereau, musée de la Libération de Paris – musée-Général Leclerc – musée Jean Moulin © Pierre Antoine CONTENTS INTRODUCTION page 04 EDITORIALS page 05 THE MUSEUM OF TOMORROW: THE CHALLENGES page 06 THE MUSEUM OF TOMORROW: THE CHALLENGES A NEW HISTORICAL PRESENTATION page 07 AN EXHIBITION IN STEPS page 08 JEAN MOULIN (¡¢¢¢£¤) page 11 PHILIPPE DE HAUTECLOCQUE (¢§¢£¨) page 12 SCENOGRAPHY: THE CHOICES page 13 ENHANCED COLLECTIONS page 15 3 DONATIONS page 16 A MUSEUM FOR ALL page 17 A HERITAGE SETTING FOR A NEW MUSEUM page 19 THE INFORMATION CENTRE page 22 THE EXPERT ADVISORY COMMITTEE page 23 PARTNER BODIES page 24 SCHEDULE AND FINANCING OF THE WORKS page 26 SPONSORS page 27 PROJECT PERSONNEL page 28 THE CITY OF PARIS MUSEUM NETWORK page 29 PRESS VISUALS page 30 LE MUSÉE DE LA LIBÉRATION DE PARIS MUSÉE DU GÉNÉRAL LECLERC MUSÉE JEAN MOULIN INTRODUCTION New presentation, new venue: the museums devoted to general Leclerc, the Liberation of Paris and Resistance leader Jean Moulin are leaving the Gare Montparnasse for the Ledoux pavilions on Place Denfert-Rochereau. -

Le Saxophone: La Voix De La Musique Moderne an Honors

Le Saxophone: La Voix de La Musique Moderne An Honors Thesis by Nathan Bancroft Bogert Dr. George Wolfe Ball State University Muncie, Indiana April 2008 May 3, 2008 Co Abstract This project was designed to display the versatility of the concert saxophone. In order to accomplish this lofty goal, a very diverse selection of repertoire was chosen to reflect the capability of the saxophone to adapt to music of all different styles and time periods. The compositions ranged from the Baroque period to even a new composition written specifically for this occasion (written by BSU School of Music professor Jody Nagel). The recital was given on February 21, 2008 in Sursa Hall on the Ball State University campus. This project includes a recording of the performance; both original and compiled program notes, and an in-depth look into the preparation that went into this project from start to finish. Acknowledgements, I would like to thank Dr. George Wolfe for his continued support of my studies and his expert guidance. Dr. Wolfe has been an incredible mentor and has continued his legacy as a teacher of the highest caliber. I owe a great deal of my success to Dr. Wolfe as he has truly made countless indelible impressions on my individual artistry. I would like to thank Dr. James Ruebel of the Ball State Honors College for his dedication to Ball State University. His knowledge and teaching are invaluable, and his dedication to his students are tings that make him the outstanding educator that he is. I would like to thank the Ball State School of Music faculty for providing me with so many musical opportunities during my time at Ball State University. -

Manuel De Falla's Homenajes for Orchestra Ken Murray

Manuel de Falla's Homenajes for orchestra Ken Murray Manuel de Falla's Homenajes suite for or- accepted the offer hoping that conditions in Ar- chestra was written in Granada in 1938 and given gentina would be more conducive to work than in its first performance in Buenos Aires in 1939 war-tom Spain. So that he could present a new conducted by the composer. It was Falla's first work at these concerts, Falla worked steadily on major work since the Soneto a Co'rdoba for voice the Homenajes suite before leaving for Argentina. and harp (1927) and his first for full orchestra On the arrival of Falla and his sister Maria del since El sombrero de tres picos, first performed in Carmen in Buenos Aires on 18 October 1939 the 1919. In the intervening years Falla worked on suite was still not ~omplete.~After a period of Atldntida (1926-46), the unfinished work which revision and rehearsal, the suite was premiered on he called a scenic cantata. Falla died in 1946 and 18 ~ovember1939 at the Teatro Col6n in Buenos the Homenajes suite remains his last major original Aires. Falla and Maria del Carmen subsequently work. The suite consists of four previously remained in Argentina where Falla died on 14 composed pieces: Fanfare sobre el nombre de November 1946. Arbds (1933); orchestrations of the Homenaje 'Le Three factors may have motivated Falla to tombeau de Claude Debussy' (1920) for solo combine these four Homenajes into an orchestral guitar; Le tombeau de Paul Dukas (1935) for pi- suite. He may have assembled the suite in order to ano; and Pedrelliana (1938) which-wasconceived give a premiere performance in Argentina. -

Alfred Desenclos

FRENCH SAXOPHONE QUARTETS Dubois Pierné Françaix Desenclos Bozza Schmitt Kenari Quartet French Saxophone Quartets Dubois • Pierné • Françaix • Desenclos • Bozza • Schmitt Invented in Paris in 1846 by Belgian-born Adolphe Sax, conductor of the Concerts Colonne series in 1910, Alfred Desenclos (1912-71) had a comparatively late The Andante et Scherzo, composed in 1943, is the saxophone was readily embraced by French conducting the world première of Stravinsky’s ballet The start in music. During his teenage years he had to work to dedicated to the Paris Quartet. This enjoyable piece is composers who were first to champion the instrument Firebird on 25th June 1910 in Paris. support his family, but in his early twenties he studied the divided into two parts. A tenor solo starts the Andante through ensemble and solo compositions. The French Pierné’s style is very French, moving with ease piano at the Conservatory in Roubaix and won the Prix de section and is followed by a gentle chorus with the other tradition, expertly demonstrated on this recording, pays between the light and playful to the more contemplative. Rome in 1942. He composed a large number of works, saxophones. The lyrical quality of the melodic solos homage to the élan, esprit and elegance delivered by this The Introduction et variations sur une ronde populaire which being mostly melodic and harmonic were often continues as the accompaniment becomes busier. The unique and versatile instrument. was composed in 1936 and dedicated to the Marcel Mule overlooked in the more experimental post-war period. second section is fast and lively, with staccato playing and Pierre Max Dubois (1930-95) was a French Quartet. -

Andre Malraux's Devotion to Caesarism Erik Meddles Regis University

Regis University ePublications at Regis University All Regis University Theses Spring 2010 Partisan of Greatness: Andre Malraux's Devotion to Caesarism Erik Meddles Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Meddles, Erik, "Partisan of Greatness: Andre Malraux's Devotion to Caesarism" (2010). All Regis University Theses. 544. https://epublications.regis.edu/theses/544 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Regis University Theses by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regis University Regis College Honors Theses Disclaimer Use of the materials available in the Regis University Thesis Collection (“Collection”) is limited and restricted to those users who agree to comply with the following terms of use. Regis University reserves the right to deny access to the Collection to any person who violates these terms of use or who seeks to or does alter, avoid or supersede the functional conditions, restrictions and limitations of the Collection. The site may be used only for lawful purposes. The user is solely responsible for knowing and adhering to any and all applicable laws, rules, and regulations relating or pertaining to use of the Collection. All content in this Collection is owned by and subject to the exclusive control of Regis University and the authors of the materials. It is available only for research purposes and may not be used in violation of copyright laws or for unlawful purposes. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science the New

The London School of Economics and Political Science The New Industrial Order: Vichy, Steel, and the Origins of the Monnet Plan, 1940-1946 Luc-André Brunet A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, July 2014 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 87,402 words. 2 Abstract Following the Fall of France in 1940, the nation’s industry was fundamentally reorganised under the Vichy regime. This thesis traces the history of the keystones of this New Industrial Order, the Organisation Committees, by focusing on the organisation of the French steel industry between the end of the Third Republic in 1940 and the establishment of the Fourth Republic in 1946. It challenges traditional views by showing that the Committees were created largely to facilitate economic collaboration with Nazi Germany. -

The Demarcation Line

No.7 “Remembrance and Citizenship” series THE DEMARCATION LINE MINISTRY OF DEFENCE General Secretariat for Administration DIRECTORATE OF MEMORY, HERITAGE AND ARCHIVES Musée de la Résistance Nationale - Champigny The demarcation line in Chalon. The line was marked out in a variety of ways, from sentry boxes… In compliance with the terms of the Franco-German Armistice Convention signed in Rethondes on 22 June 1940, Metropolitan France was divided up on 25 June to create two main zones on either side of an arbitrary abstract line that cut across départements, municipalities, fields and woods. The line was to undergo various modifications over time, dictated by the occupying power’s whims and requirements. Starting from the Spanish border near the municipality of Arnéguy in the département of Basses-Pyrénées (present-day Pyrénées-Atlantiques), the demarcation line continued via Mont-de-Marsan, Libourne, Confolens and Loches, making its way to the north of the département of Indre before turning east and crossing Vierzon, Saint-Amand- Montrond, Moulins, Charolles and Dole to end at the Swiss border near the municipality of Gex. The division created a German-occupied northern zone covering just over half the territory and a free zone to the south, commonly referred to as “zone nono” (for “non- occupied”), with Vichy as its “capital”. The Germans kept the entire Atlantic coast for themselves along with the main industrial regions. In addition, by enacting a whole series of measures designed to restrict movement of people, goods and postal traffic between the two zones, they provided themselves with a means of pressure they could exert at will. -

1 the Liberation : Myths and History Perhaps More Than Any Other

L2: WW2 France & the Historians: Libération 1 The Liberation : myths and history Perhaps more than any other aspect of the Second World War, the Libération was the subject of myth-making, at the time and subsequently. This should not surprise us. Contemoraries were conscious of living an historic moment, one that seemed like the reversal of the verdict of 1940. For those in the Resistance or the Free French, it was an apotheosis. For their antagonists, collaborating directly with the Germans (the French fascists) or supporters of Vichy, it was a nemesis. For everyone, it raised the alternatives of whether this was the end of a bitterly divisive parenthesis and a return to normality or the start of a radically new phase in French history, perhaps even a revolution of sorts. Wherever one stood, the stakes could not have been higher. So it is no wonder that historical meaning was imparted to the Libération at the time and afterwards by politicians and others. The question for us is what sense have historians made of the Libération, whether as part of this broader ascription of meaning to the end of the Occupation or independently of it. The more or less instantaneous myth-making is evidenced by de Gaulle’s speech with which we began course, suggesting central idea of ‘self-liberation’, and also the PCF emerging from clandestinity with image of the FFI as a kind of popular unrising, incarnating justice against the collaborators. Chronologically, the Libération was spread over ten months, from June 1944 to May 1945. But the epicentre was July-August 1944, once the Allies broke out of the Normandy beacheads and also landed in Provence. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Quality of This Reproduction Is

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMZ films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter &ce, while others nuy be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the qualityof the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the origina!, b^inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell ft Howdl Infbnnatioa Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Aitor MI 4SI06-I346 USA 313/761-4700 «00/321-0600 THE PRICE OF DREAMS: A HISTORY OF ADVERTISING IN FRANCE. 1927-1968 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Clark Eric H ultquist, B.A., M.A. -

Rome Vaut Bien Un Prix. Une Élite Artistique Au Service De L'état : Les

Artl@s Bulletin Volume 8 Article 8 Issue 2 The Challenge of Caliban 2019 Rome vaut bien un prix. Une élite artistique au service de l’État : Les pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome de 1666 à 1968 Annie Verger Artl@s, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Verger, Annie. "Rome vaut bien un prix. Une élite artistique au service de l’État : Les pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome de 1666 à 1968." Artl@s Bulletin 8, no. 2 (2019): Article 8. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. This is an Open Access journal. This means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. This journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license. Artl@s At Work Paris vaut bien un prix. Une élite artistique au service de l’État : Les pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome de 1666 à 1968 Annie Verger* Résumé Le Dictionnaire biographique des pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome a essentiellement pour objet le recensement du groupe des praticiens envoyés en Italie par l’État, depuis Louis XIV en 1666 jusqu’à la suppression du concours du Prix de Rome en 1968. -

000000018 1.Pdf

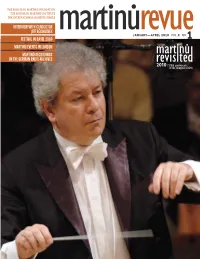

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE THE INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE INTERVIEW WITH CONDUCTOR JIŘÍ BĚLOHLÁVEK martinůJANUARY—APRILrevue 2010 VOL.X NO. FESTIVAL IN BASEL 2009 1 MARTINŮ EVENTS IN LONDON MARTINŮ RECORDINGS ķ IN THE GERMAN RADIO ARCHIVES contents 3 Martinů Revisited Highlights 4 news —Anna Fárová Dies —Zdeněk Mácal’s Gift 5 International Martinů Circle 6 festivals —The Fruit of Diligent and Relentless Activity CHRISTINE FIVIAN 8 interview …with Jiří Bělohlávek ALEŠ BŘEZINA 9 Liturgical Mass in Prague MILAN ČERNÝ 10 News from Polička LUCIE JIRGLOVÁ UP 0121-2 11 special series —List of Martinů’s Works VIII 12 research —Martinů Treasures in the German Radio Archives GREGORY TERIAN 13 review —Martinů in Scotland GREGORY TERIAN 14 review —Czech Festival in London UP 0123-2 UP 0126-2 PATRICK LAMBERT 16 festivals —Bohuslav Martinů Days 2009 PETR VEBER 17 news / conference 18 events 19 news UP 0106-2 UP 0122-2 UP 0116-2 —New CDs, Publications ARCODIVA Jaromírova 48, 128 00 Praha 2, Czech Republic tel.: +420 223 006 934, +420 777 687 797 • fax: +420 223 006 935 e-mail: [email protected] ķ highlights IN 2010 TOO WE ARE CELEBRATING a momentous anniversary – 120 years since the birth of Bohuslav Martinů (8 December 1890, Polička). Numerous ensembles and music organisations have included Martinů works in their 2010 repertoire. We will keep you up to date on this page with the most significant events. MORE INFORMATION > www.martinu.cz > www.czechmusic.org ‹vFESTIVALS—› The 65th Prague Spring The 65th PRAGUE SPRING INTERNATIONAL MUSIC FESTIVAL International Music Festival Prague, 12 May—4 June 2010 Prague / 12 May—4 June 2010 www.festival.cz 15 May 2010, 11.00 am > Martinů Hall, Lichtenštejn Palace Scherzo, H. -

The Geopolitics of Laïcité in a Multicultural Age: French Secularism, Educational Policy and the Spatial Management of Difference

The Geopolitics of Laïcité in a Multicultural Age: French Secularism, Educational Policy and the Spatial Management of Difference Christopher A. Lizotte A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Katharyne Mitchell, Chair Victoria Lawson Michael Brown Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Geography ©Copyright 2017 Christopher A. Lizotte University of Washington Abstract The Geopolitics of Laïcité in a Multicultural Age: French Secularism, Educational Policy and the Spatial Management of Difference Christopher A. Lizotte Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Katharyne Mitchell Geography I examine a package of educational reforms enacted following the January 2015 attacks in and around Paris, most notably directed at the offices of the satirical publication Charlie Hebdo. These interventions, known collectively as the “Great Mobilization for the Republic’s Values”, represent the latest in a string of educational attempts meant to reinvigorate a sense of national pride among immigrant-descended youth – especially Muslim – in France’s unique form of state secularism, laïcité. While ostensibly meant to apply equally across the nationalized French school system, in practice La Grande Mobilisation has been largely enacted in schools located in urban spaces of racialized difference thought to be “at risk” of anti-republican behavior. Through my work, I show that practitioners exercise their own power by subverting and adapting geopolitical discourses running through educational laïcité – notably global security, women’s rights, and communalism – are nuanced by school-based practitioners, who interpret state directives in the light of their institutional knowledge and responsiveness to the social and economic profiles of their student populations.