Charles Fort

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WG Sebald and Outsider

Writing from the Periphery: W. G. Sebald and Outsider Art by Melissa Starr Etzler A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Winfried Kudszus, Chair Professor Anton Kaes Professor Anne Nesbet Spring 2014 Abstract Writing from the Periphery: W. G. Sebald and Outsider Art by Melissa Starr Etzler Doctor of Philosophy in German and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Winfried Kudszus, Chair This study focuses on a major aspect of literature and culture in the later twentieth century: the intersection of psychiatry, madness and art. As the antipsychiatry movement became an international intervention, W. G. Sebald’s fascination with psychopathology rapidly developed. While Sebald collected many materials on Outsider Artists and has several annotated books on psychiatry in his personal library, I examine how Sebald’s thought and writings, both academic and literary, were particularly influenced by Ernst Herbeck’s poems. Herbeck, a diagnosed schizophrenic, spent decades under the care of Dr. Leo Navratil at the psychiatric institute in Maria Gugging. Sebald became familiar with Herbeck via the book, Schizophrenie und Sprache (1966), in which Navratil analyzed his patients’ creative writings in order to illustrate commonalities between pathological artistic productions and canonical German literature, thereby blurring the lines between genius and madness. In 1980, Sebald travelled to Vienna to meet Ernst Herbeck and this experience inspired him to compose two academic essays on Herbeck and the semi-fictionalized account of their encounter in his novel Vertigo (1990). -

Franz A. Birgel Muhlenberg College

Werner Herzog's Debt to Georg Buchner Franz A. Birgel Muhlenberg College The filmmaker Wemcr Herzog has been labeled eve1)1hing from a romantic, visionary idealist and seeker of transcendence to a reactionary. regressive fatalist and t)Tannical megalomaniac. Regardless of where viewers may place him within these e:-..1reme positions of the spectrum, they will presumably all admit that Herzog personifies the true auteur, a director whose unmistakable style and wor1dvie\v are recognizable in every one of his films, not to mention his being a filmmaker whose art and projected self-image merge to become one and the same. He has often asserted that film is the art of i1literates and should not be a subject of scholarly analysis: "People should look straight at a film. That's the only \vay to see one. Film is not the art of scholars, but of illiterates. And film culture is not analvsis, it is agitation of the mind. Movies come from the count!)' fair and circus, not from art and academicism" (Greenberg 174). Herzog wants his ideal viewers to be both mesmerized by his visual images and seduced into seeing reality through his eyes. In spite of his reference to fairgrounds as the source of filmmaking and his repeated claims that his ·work has its source in images, it became immediately transparent already after the release of his first feature film that literature played an important role in the development of his films, a fact which he usually downplays or effaces. Given Herzog's fascination with the extremes and mysteries of the human condition as well as his penchant for depicting outsiders and eccentrics, it comes as no surprise that he found a kindred spirit in Georg Buchner whom he has called "probably the most ingenious writer for the stage that we ever had" (Walsh 11). -

DOUBT Was Described "By Scientists" As Siderable Poet and Fire-Spouting Rebel

THE No. 14 EDITED BY IFF 202 203 PHILLY TARGET? made many forget that he was once a con observing their reactions. Funny - he never DOUBT was described "by scientists" as siderable poet and fire-spouting rebel. Early did see the similarity between himself and brilliant (bolide) in many years'' in life, he had sublime self-confidence and those monkeys. It never occurred to him T;h�· Fortean Society Magazine in the sky to the east of Philadel a grand ·impatience with all Philistines. that they had objections to being stuck with Because publishers could make no money Edited by TIFFANY THAYER phia "a few minutes after 3 o'clock thi� needles full of infection - for the good (10-21-45 from his books they rejected them, but of their jailors. But a beneficent god pass Secretary of tile old style) morning." Which re calls a similar occurrence on the morning of De Casseres had the courage to print them ing that way was not so blind as Dugan, FORTEAN SOCIETY 5-4-45 old style at 3:38. The May meteor himself, in the face of widespread popular and when he saw what the Conscientious Box 192 Grand Central Annex got much more publicity than this one in scorn for that practice. He employed no Objector was doing to the helpless monkey, "vanity publi�her", nor was his motive vain. New York City October, although judging from the above �e let a scratch admit the virus into Dugan's data it was the smaller of the two. Also - Read anything he wrote before 1925 to system - and kill him. -

Newsletter 1

NEWSLETTER 1 Frühjahr / Spring 2018 Kaspar Hauser Forschungskreis Kaspar Hauser Research Circle www.kaspar-hauser.net Published by the Kaspar Hauser Forschungkreis at the Karl König Institute Berlin · Editors: Eckart Böhmer, Richard Steel, Winfried Altmann Eckart Böhmer Eckart Böhmer Willkommen Welcome zum ersten Newsletter to our first Newsletter! Nun kann der Kaspar Hauser For- (Stuttgart). Gut 20 Kisten konnten wir This first Newsletter of the Kaspar schungskreis auf das erste Jahr seiner bereits katalogisieren, wobei wir schon Hauser Research Circle already looks Tätigkeit zurückblicken. Und wir kön- einige Schätze finden konnten. back at one year of activity since the nen sagen, dass einige wichtige und gute Ein wichtiger Punkt darunter ist bei- founding at Michaelmas 2016. And we Dinge geschehen sind! So war es bei- spielsweise der Briefaustausch zwischen are happy to note that much has happe- spielsweise möglich, ein gutes Büro zu Jakob Wassermann und Hermann Pies. ned in that time! Since then a very good finden, das auch über genügend Stau- Ein schöner Artikel hierzu, mit den Ab- office has been found for the Karl König raum verfügt. Und da es sich um einen bildungen der Originale, findet sich auf Institute where there is enough space to Neubau handelt, ist auch für ausrei- unserer Webseite, verfasst von Dorothea begin with the archiving of the many chende Trockenheit gesorgt, was für die Sonstenes. Dieser Austausch belegt die books and documents for which we have vielen Kisten des Nachlasses von nicht Schlüsselposition, die Wassermann für taken responsibility. It is of great impor- zu unterschätzender Wichtigkeit ist. Im Hermann Pies inne hatte, sodass er als tance for archiving, that this building Haus, das sich im Besitz der Christenge- Impulsgeber gesehen werden kann für provides storage space with a climate meinschaft Kleinmachnow befindet, die dann folgende Lebensaufgabe des safe for the documents. -

Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction

Andrew May Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction Editorial Board Mark Alpert Philip Ball Gregory Benford Michael Brotherton Victor Callaghan Amnon H Eden Nick Kanas Geoffrey Landis Rudi Rucker Dirk Schulze-Makuch Ru€diger Vaas Ulrich Walter Stephen Webb Science and Fiction – A Springer Series This collection of entertaining and thought-provoking books will appeal equally to science buffs, scientists and science-fiction fans. It was born out of the recognition that scientific discovery and the creation of plausible fictional scenarios are often two sides of the same coin. Each relies on an understanding of the way the world works, coupled with the imaginative ability to invent new or alternative explanations—and even other worlds. Authored by practicing scientists as well as writers of hard science fiction, these books explore and exploit the borderlands between accepted science and its fictional counterpart. Uncovering mutual influences, promoting fruitful interaction, narrating and analyzing fictional scenarios, together they serve as a reaction vessel for inspired new ideas in science, technology, and beyond. Whether fiction, fact, or forever undecidable: the Springer Series “Science and Fiction” intends to go where no one has gone before! Its largely non-technical books take several different approaches. Journey with their authors as they • Indulge in science speculation—describing intriguing, plausible yet unproven ideas; • Exploit science fiction for educational purposes and as a means of promoting critical thinking; • Explore the interplay of science and science fiction—throughout the history of the genre and looking ahead; • Delve into related topics including, but not limited to: science as a creative process, the limits of science, interplay of literature and knowledge; • Tell fictional short stories built around well-defined scientific ideas, with a supplement summarizing the science underlying the plot. -

1931 Article Titles and Notes Vol. III, No. 1, January 10, 19311

1931 article titles and notes Vol. III, No. 1, January 10, 19311 "'The Youngest' Proves Entertaining Production of Players' Club. Robert W. Graham Featured in Laugh Provoking Comedy; Unemployed to Benefit" (1 & 8 - AC, CO, CW, GD, and LA) - "Long ago it was decided that the chief aim of the Players' Club should be to entertain its members rather than to educate them or enlighten them on social questions or use them as an element in developing new ideas and methods in the Little Theatre movement."2 Philip Barry's "The Youngest" fit the bill very well. "Antiques, Subject of Woman's Club. Chippendale Furniture Discussed by Instructor at School of Industrial Art. Art Comm. Program" (1 - AE and WO) - Edward Warwick, an instructor at the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art, spoke to the Woman's Club on "The Chippendale Style in America." "Legion Charity Ball Jan. 14. Tickets Almost Sold Out for Benefit Next Friday Evening. Auxiliary Assisting" (1 & 4 - CW, LA, MO, SN, VM, and WO) - "What was begun as a Benefit Dance for the Unemployed has grown into a Charity Ball sponsored by the local America Legion Post with every indication of becoming Swarthmore's foremost social event of the year." The article listed the "patrons and patronesses" of the dance. Illustration by Frank N. Smith: "Proposed Plans for New School Gymnasium" with caption "Drawings of schematic plans for development of gymnasium and College avenue school buildings" (1 & 4 - BB, CE, and SC) - showed "how the 1.035 acres of ground just west of the College avenue school which was purchased from Swarthmore College last spring might be utilized for the enlargement of the present building into a single school plant." "Fortnightly to Meet on Monday" (1 - AE and WO) - At Mrs. -

Ellery Queen Master Detective

Ellery Queen Master Detective Ellery Queen was one of two brainchildren of the team of cousins, Fred Dannay and Manfred B. Lee. Dannay and Lee entered a writing contest, envisioning a stuffed‐shirt author called Ellery Queen who solved mysteries and then wrote about them. Queen relied on his keen powers of observation and deduction, being a Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson rolled into one. But just as Holmes needed his Watson ‐‐ a character with whom the average reader could identify ‐‐ the character Ellery Queen had his father, Inspector Richard Queen, who not only served in that function but also gave Ellery the access he needed to poke his nose into police business. Dannay and Lee chose the pseudonym of Ellery Queen as their (first) writing moniker, for it was only natural ‐‐ since the character Ellery was writing mysteries ‐‐ that their mysteries should be the ones that Ellery Queen wrote. They placed first in the contest, and their first novel was accepted and published by Frederick Stokes. Stokes would go on to release over a dozen "Ellery Queen" publications. At the beginning, "Ellery Queen" the author was marketed as a secret identity. Ellery Queen (actually one of the cousins, usually Dannay) would appear in public masked, as though he were protecting his identity. The buying public ate it up, and so the cousins did it again. By 1932 they had created "Barnaby Ross," whose existence had been foreshadowed by two comments in Queen novels. Barnaby Ross composed four novels about aging actor Drury Lane. After it was revealed that "Barnaby Ross is really Ellery Queen," the novels were reissued bearing the Queen name. -

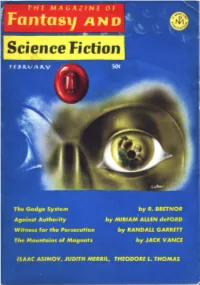

This Month's Issue

FEBRUARY Including Venture Science Fiction NOVELETS Against Authority MIRIAM ALLEN deFORD 20 Witness for the Persecution RANDALL GARRETT 55 The Mountains of Magnatz JACK VANCE 102 SHORT STORIES The Gadge System R. BRETNOR 5 An Afternoon In May RICHARD WINKLER 48 The New Men JOANNA RUSS 75 The Way Back D. K. FINDLAY 83 Girls Will Be Girls DORIS PITKIN BUCK 124 FEATURES Cartoon GAHAN WILSON 19 Books JUDITH MERRIL 41 Desynchronosis THEODORE L. THOMAS 73 Science: Up and Down the Earth ISAAC ASIMOV 91 Editorial 4 F&SF Marketplace 129 Cover by George Salter (illustrating "The Gadge System") Joseph W. Ferman, PUBLISHER Ed~mrd L. Fcrma11, EDITOR Ted White, ASSISTANT EDITOR Isaac Asimov, SCIENCE EDITOR Judith Merril, BOOK EDITOR Robert P. llfil/s, CONSULTING EDITOR The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Volnme 30, No. 2, Wlrolc No. 177, Feb. 1966. Plfblished monthly by Mercury Press, Inc., at 50¢ a copy. Aunual subscription $5.00; $5.50 in Canada and the Pan American Union, $6.00 in all other cormtries. Publication office, 10 Ferry Street, Concord, N.H. 03302. Editorial and ge11eral mail sholfld be sent to 3/7 East 53rd St., New York, N. Y. 10022. Second Class postage paid at Concord, N.H. Printed in U.S.A. © 1965 by Mercury Press, Inc. All riglrts inc/fl.ding translations iuto ot/rer la~>guages, resen•cd. Submissions must be accompanied by stamped, self-addressed ent•ciBPes; tire Publisher assumes no responsibility for retlfm of uusolicitcd ma1111scripts. BDITOBIAL The largest volume of mail which crosses our desk each day is that which is classified in the trade as "the slush pile." This blunt term is usually used in preference to the one y11u'll find at the very bottom of our contents page, where it says, ". -

Based on a True Story: a Critical Approach to Ambiguous Veracity in Literature

Based on a True Story: a Critical Approach to Ambiguous Veracity in Literature The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Selsby, Noah. 2019. Based on a True Story: a Critical Approach to Ambiguous Veracity in Literature. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42004083 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Based on a True Story: A Critical Approach to Ambiguous Veracity in Literature Noah Selsby A Thesis in the Field of English for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University March 2019 Copyright 2019 Noah Selsby Abstract The statement that a work is “based on a true story” is one which is inherently ambiguous as the degree to which the story is factual or invented can be unknown unless directly addressed by the author. As a result, there is a tension felt when this claim is made at the beginning of a text with which a reader is unfamiliar, leading to the risk of assuming which parts of the narrative are true and which were fabricated. This thesis will explore several texts and works of narrative art which bare the markings of being “based on a true story,” but which challenge the reader to think critically when comparing their contents to verifiable sources. -

Sixth- OVER 1,000 Attended the Ms

THE * W C H iY A L STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE WEDNESDAY, 6th FEBRUARY, 1980 No. 628. PRICE: 5p THREAT TO N.U.S.? RAG MAG THE Anti-National Union sible student challenges the by the governing authorities. would be saved by disaffiliation, N.U.S. movement we will res A proposed change in the of Students group As the actual contribution government allocation of the particularly as there has been pond accordingly. I do not ner student amounts to only a capitation fee, will mean that a cut of thirty per cent in the (A .N .U .S .) appears to be regard A.N.U.S. as an organis little over two pounds, it instead of this being .paid by grants to S.R.C. societies. In SALE gaining support amongst ation which legitimately rep appears that the membership oflocal authorities it will be addition to the cost of mem resents the views of a some Newcastle students. N.U.S. are getting exceedingly controlled from a central bership, approximately £2,000 significant number of good value for money. Tund. However, the actual is spent annually on sending The movement claims students” . Secretary Claire Sheehan amount which is paid on be delegates to N.U.S. Con that disaffiliation from Nigel Wild said that he felt has given a concise breakdown half of each student will ferences. the leaders of the “anti” move BANNED the national body will of the contribution of New probably be reduced. The student body as a ment had been significantly castle University students to In view of this there is a influenced by their own pre whole will have the opportunity save over £13,000 a year, its present organisation. -

Chapter 4 “What If I Never See You Again”

Chapter 4 “What If I Never See You Again” He barely got out the words, “Oh, my God. The Mary Celeste . Brad . It’s the Mary Celeste!” His friend slowly turned and faced him, then looked stupefied to where Sarantos was pointing. His jaw dropped and his eyebrows elevated causing his dark brown eyes to bulge out of their sockets. Brad’s shocked look conveyed what Sarantos wanted to say, but there were no words strong enough to properly explain what their current situation appeared to be. The two friends stood side-by-side glaring at the letters while trying to get their heads around the reality of what it was they were seeing. Finally, Brad cleared his throat and managed to stutter some words. “Thi-s isn’t our w--orld.” Sarantos looked at his friend to see if he was okay. He didn’t like the sound of his quivering voice. “What? Of course, it’s your world, Brad. What’s wrong with you?” The wizard blurted out hastily while looking very perplexed. “No, it’s not.” Sarantos said rather flatly. The wizard raised his staff and bellowed, “You’re both mad. Of course, it’s your world, because I said it is and I know these things. I’m a wizard for crying out loud!” “No, you don’t understand, Wallis. It’s earth, but not earth as we knew it. The time period is wrong. The 1 Mary Celeste was found abandoned in 1872, a ghost ship.” Brad paused and Sarantos lifted his eyes to stare at his friend who was still both shocked and amazed. -

Through Gendered Lenses 2017 Vol

Undergraduate Academic Journal of Gender Research and Scholarship Through Gendered Lenses 2017 Vol. 8 The Gender Studies Honor Society and The Gender Studies Program University of Notre Dame Cover Design: Gabriela Leskur About the Artist Gabriela Leskur is a 2017 Bachelor of Fine Arts candidate in Visual Communication Design. Her work focuses on how visuals may aid in the dissemination of meaningful messages while utilizing a variety of techniques and tools, from traditional graphic design to 3D modeling to performance art. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................... 4 The Gender Studies Program ............................................................................ 6 Triota: The Gender Studies Honor Society ................................................. 7 Triota Members ...................................................................................................... 8 Letter from the Editor .......................................................................................... 9 About the Editor ................................................................................................... 10 Essays “I am the Lord of the Dance,” Said He: Deconstructing Toxic Masculinity in Michael Flatley’s Lord of the Dance Moira Horn .............................................................................................................. 12 Compassionate Care for Victims of Sexual Assault Malavika Praseed ................................................................................................