(Almost) Everything

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Half Fanatics August 2014 Newsletter

HALF FANATICS AUGUST 2014 NEWSLETTER Angela #8730 NEWSLETTER CONTENTS Race Photos ...…………….. 1 Featured Fanatic…………... 2 Expo Schedule………………3 Fanatic Poll…………………..3 Sporty Diva Half Marathon Upcoming Races…………… 5 HF Membership Criteria…... 7 Jamila #3959, Loan #4026, Alicia, and BustA Groove #3935 Half Fanatic Pace Team…. ..7 Meghan #7202 New HF Gear……………….. .8 New Moons………………….. 8 Welcome to the Asylum…... 9 Shaun #7485 & Cathy #1756 Meliessa #8722 1 http://www.halffanatics.com 1 HALF FANATICS AUGUST 2014 NEWSLETTER Featured Fanatic Yvette Todd, Half Fanatic #5517 “50 in 50” and Embracing the Sun The idea of my challenge was borne in June 2011. I met a fellow camper/runner at the Colworth Marathon Challenge running event - 3 races, 3 days, 26.2 miles. The runner was extremely pleased to be there as he was able to bag 3 races in one weekend for what he called his “50 in 50 challenge” - 50 running events in his 50th year. Inspired, I decided to cele- brate this landmark age by doing 50 half marathons as a 50 year old - my own version of the “50 in 50” and planned to start the challenge right after I ran a mara- thon on my 50th birthday! Two challenges? Well the last one, I have been dreaming about for a few years, in fact, ever since I did the New York Marathon back in 2006 where I met a fellow lady runner staying in the same hotel as me. She was ecstatic the whole weekend as she was running the New York marathon on her actual 50th birthday. -

Implementing Screens Within Screens to Create Telepresence in Reality TV

Implementing screens within screens to create telepresence in reality TV Daniel Klug ∗ 1, Axel Schmidt ∗y 2 1 Institute for Media Studies, University of Basel – Suisse 2 Institute for the German Language – Allemagne Following Gumbrecht’s (2004) draft of a theory of presence the notion of presence aims at spatial relations: Something is present if it is tangible or ‘in actual range’ (Sch´’utz/Luckmann 1979). Concerning the social world, Goffman (1971) understands co-presence in a similar way, as the chance to get in direct contact with each other. For this, the possibility of mutually perceiving each other is a precondition and is in turn made possible by a shared location. Goffman’s concept of co-presence is bound to a shared here and now and thus is based on a notion of situation with place as its central dimension. Interaction as a basic mode of human exchange builds on situations and the possibility of mutual perception allowing so called perceived perceptions in particular (Hausendorf 2003) as the main mechanism of focused encounters. Media studies, however, proved that both the notion of situation as place and interaction as co-presence need to be extended as mediated contact creates new forms of situations and interactions. Especially Meyrowitz (1990) shows that the notion of situation has to be detached from the dimension of place and instead be redefined in terms of mediated contact. Therefore, the question ”who can hear me, who can see me?” is the basis for individual orientation and should guide the analysis of (inter)action. Although media enlarges the scope of perception in this way, it is not just a simple extension, but a trans- formation process in which the mediation itself plays a crucial role. -

The Not-So-Reality Television Show: Consumerism in MTV’S Sorority Life

The Not-So-Reality Television Show: Consumerism in MTV’s Sorority Life Kyle Dunst Writer’s comment: I originally wrote this piece for an American Studies seminar. The class was about consumption, and it focused on how Americans define themselves through the products they purchase. My professor, Carolyn de la Pena, really encouraged me to pursue my interest in advertising. If it were not for her, UC Davis would have very little in regards to studying marketing. —Kyle Dunst Instructor’s comment:Kyle wrote this paper for my American Studies senior seminar on consumer culture. I encouraged him to combine his interests in marketing with his personal fearlessness in order to put together a somewhat covert final project: to infiltrate the UC Davis- based Sorority Life reality show and discover the role that consumer objects played in creating its “reality.” His findings help us de-code the role of product placement in the genre by revealing the dual nature of branded objects on reality shows. On the one hand, they offset costs through advertising revenues. On the other, they create a materially based drama within the show that ensures conflict and piques viewer interest. The ideas and legwork here were all Kyle; the motivational speeches and background reading were mine. —Carolyn de la Pena, American Studies PRIZED WRITING - 61 KYLE DUNST HAT DO THE OSBOURNES, Road Rules, WWF Making It!, Jack Ass, Cribs, and 12 seasons of Real World have in common? They Ware all examples of reality-MTV. This study analyzes prod- uct placement and advertising in an MTV reality show familiar to many of the students at the University of California, Davis, Sorority Life. -

Ryan Dempsey SAG AFTRA Eligible (203)-233-0758

Ryan Dempsey SAG AFTRA Eligible (203)-233-0758 Height: 5’10 Weight: 190 Hair: Red Eyes: Hazel FILM: Party Boat Supporting SONY Pictures Studios/Mesquite Prod. /Dir: Dylan Kidd Summer Madness Supporting FIFTEEN Studios/Dir: Justin Poage Atomic Brain Invasion Supporting Scorpio Film Releasing/Dir: Richard Griffin TELEVISION / WEB SERIES: Homicide Hunter Guest-Star Jupiter Entertainment / Dir: Greg Francis Killer Couples Guest-Star Jupiter Entertainment / Dir: Brian Peery Office Secrets Co-Star Taylormade Film Company/ Dir: Tony F. Charles Mixed Emotions Co-Star E-Tre Productions/ Dir: Ernestine Johnson Room Raiders 2.0 Guest-Star MTV/Dir: Trip Swanhaus COMMERCIAL: Yard Force Principal Yard Force 3200 PSI Pressure Washer/ Dir: Nathan Shinholt Jay Morrison Academy Principal EZ Funding / Dir: Ernestine Johnson Marriott Featured Through The Madness TRAINING: Bill Walton Acting for the Camera Connecticut Eric E. Tonner Acting 1: Character Study Connecticut Eric E. Tonner Voice and Diction Connecticut Sal S. Trapani Acting 3: Period styles Connecticut Pamela D. McDaniel Acting 2: Scene Study Connecticut Pamela D. McDaniel Performance Technique Connecticut Louisa C. Burns Bisogno Screenwriting Workshop Connecticut Alessandro Folchitto/Gary Watson Tactical weapons training for film Georgia Gary Monroe Tactical Parkour for film Georgia Capt. Dale Dye Military Training for film Louisiana College Classes Western Connecticut State University, Connecticut SPECIAL SKILLS: Dialects (Irish, British, Southern, Boston), Tactical weapons training for film, Parkour with weapons, Stunt driving, Stand-Up Comedy, Improv, Bartending, Cooking, Good with Kids, Good with animals, Hand Gun experience, Assualt Rifle Experience, Shotgun Experience, Football, Baseball, Volleyball, Long-distance Runner, Belch on command, Wiggle Ears, Vibrate Eyeballs, Drivers License, Passport . -

MARISSA JOY DAVIS Sage Height: 5’5” Weight: 115 Hair: Blonde Eyes: Blue

MARISSA JOY DAVIS SAGe Height: 5’5” Weight: 115 Hair: Blonde Eyes: Blue Film Bigfoot Wars Amy Taylor Dir: Brian Jaynes Slaughter Creek Lead, Alyssa My Own Worst Enemy, Dir: Brian Skiba Temple Grandin Day Player HBO, Dir: Mick Jackson Patient Zero Day Player Dir: Brian Jaynes Television Betty Crocker Cooking Show Co-Host Betty Crocker The Jewelry Channel Host The Jewelry Channel Channel 7 News, Tyler Cooking Host NBC Room Raiders Co-Star MTV Commercial List available upon request Print Inside cover of national magazines (ask for more detail) Theater Strip Cult Samantha Hyde Out, Perish, Dir: Michael Z. Guys and Dolls Adelaide Mineola Theater, Dir: Shannon Seaton Last Night of Ballyhoo Sunny Mineola Theater, Dir: Shannon Seaton Over the River and Through the Woods Alice Mineola Theater, Dir: Shannon Seaton Assassins Emma Goldman Mineola Theater, Dir: Larry Wisdom Annie Orphan Mineola Theater, Dir: Larry Wisdom Radio 90.5 The Kat Classic Rock Disc Jockey 90.5 The Kat Sports Broadcasting Training Austin Acting Workshop Dan Fauci Austin Actors Studio, Austin, TX Abyss Dan Fauci Austin Actors Studio, Austin, TX Leadership Dan Fauci Austin Actors Studio, Austin, TX Mastery Van Brooks 2 Chairs Studio, Austin, TX Advanced Film Acting Van Brooks Austin Actors Studio, Austin, TX Private Voice Michael McKelvey St. Edwards University KD Studios Dallas, TX Musical Summer Theater Workshop University of North Texas Radio and Television Studies Sam Houston State University BA Theater/ Music Minor St. Edwards University Special Skills Voice: E below mid C to high C, Belt up to a C Athletics: Skydiving, Yoga, Swimming, Volleyball, Rollerblading, Basketball, Cheerleading, Golfing, Horseback Riding (Western and English), Softball, Firearms, Hip Hop, Ballet, Tap Dialects: Southern U.S., English, New York Instruments: Piano, Guitar Pageants: Miss Mineola, Most Photogenic Other: Valid Passport, Great with children and animals . -

Reality TV and Interpersonal Relationship Perceptions

REALITY TV AND INTERPERSONAL RELATIONSHIP PERCEPTIONS ___________________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of MissouriColumbia ______________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________________________________________ by KRISTIN L. CHERRY Dr. Jennifer Stevens Aubrey, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2008 © Copyright by Kristin Cherry 2008 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled REALITY TV AND INTERPERSONAL RELATIONSHIP PERCEPTIONS presented by Kristin L. Cherry, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Jennifer Stevens Aubrey Professor Michael Porter Professor Jon Hess Professor Mary Jeanette Smythe Professor Joan Hermsen ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge all of my committee members for their helpful suggestions and comments. First, I would like to thank Jennifer Stevens Aubrey for her direction on this dissertation. She spent many hours providing comments on earlier drafts of this research. She always made time for me, and spent countless hours with me in her office discussing my project. I would also like to thank Michael Porter, Jon Hess, Joan Hermsen, and MJ Smythe. These committee members were very encouraging and helpful along the process. I would especially like to thank them for their helpful suggestions during defense meetings. Also, a special thanks to my fiancé Brad for his understanding and support. Finally, I would like to thank my parents who have been very supportive every step of the way. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………..ii LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………..…….…iv LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………….……v ABSTRACT………………………………………………………….…………………vii Chapter 1. -

06 11:22 (TV Guide).Pdf

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, November 22, 2005 Monday Evening November 28, 2005 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Wife Swap Monday Night Football Jimmy K KBSH/CBS King/Que How I Met 2 1/2 Men Out of Pra CSI Miami Local Late Show Late Late KSNK/NBC Surface Las Vegas Medium Local Tonight Show Conan FOX Prison Break Prison Break Local Local Local Local Local Local Cable Channels A&E The Child Sex Trade Growing Up Gotti Airline Airline Crossing Jordan The Child Sex Trade AMC The Ref Tommy Boy The Ref ANIM Miami Animal Police Animal Precinct Miami Animal Police Miami Animal Police Animal Precinct CNN Paula Zahn Now Larry King Live Anderson Cooper Larry King Norton TV DISC Roush Racing Monster Garage American Chopper American Chopper Roush Racing DISN Disney Movie Raven Sis Bug Juice Lizzie Boy Meets Even E! THS Dr. 90210 E!ES Palms Soup ESPN Monday Night Countdown Figure Skating Sportscenter ESPN2 Big Ten Challenge Chopper Town Trucker St Hollywood Frankly FAM Blizzard Whose Lin Whose Lin 700 Club Funniest Home Video FX High Crimes Nip/Tuck That 70's That 70's HGTV Cash/Attic Dream Ho I Did! Designed Buy Me Rezoned Dime DoubleTa Cash/Attic Dream Ho HIST UFO Files Decoding The Past Battlefield Detectives Digging for the Truth UFO Files LIFE Christmas in My Hometown Crazy For Christmas Will/Grace Will/Grace Golden Girls MTV Real World Punk'd Miss Seve Room Raiders Wanted Room Rai Listings: NICK SpongeBo Drake Full Hous Full Hous Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes SCI Stargate SG-1 Stargate SG-1 Stargate -

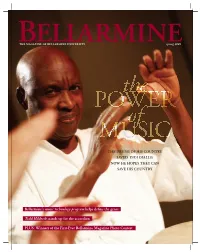

Bellarmine's Music Technology Program Helps Define the Genre Todd Hildreth Stands up for the Accordion PLUS

THE MAGAZINE OF BELLARMINE UNIVERSITY spring 2009 the POWER of MUSIC THE DRUMS OF HIS COUNTRY SAVED YAYA DIALLO; NOW HE HOPES THEY CAN SAVE HIS COUNTRY Bellarmine’s music technology program helps define the genre Todd Hildreth stands up for the accordion PLUS: Winners of the First-Ever Bellarmine Magazine Photo Contest 2 BELLARMINE MAGAZINE TABLE of CEONT NTS 5 FROM THE PRESIDENT Helping Bellarmine navigate tough times 6 THE READERS WRITE Letters to the editor 7 ‘SUITE FOR RED RIVER GORGE, PART ONE’ A poem by Lynnell Edwards 7 WHAT’S ON… The mind of Dr. Kathryn West 8 News on the Hill 14 FIRST-EVER BELLARMINE MAGAZINE PHOTO CONTEST The winners! 20 QUESTION & ANSWER Todd Hildreth has a squeezebox – and he’s not afraid to use it 22 DRUM CIRCLE Yaya Diallo’s music has taken him on an amazing journey 27 CONCORD CLASSIC This crazy thing called the Internet 28 BELLARMINE RADIO MAKES SOME NOISE Shaking up the lineup with more original programming 32 NEW HARMONY Fast-growing music technology program operates between composition and computers 34 CLASS NOTES 36 Alumni Corner 38 THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION COVER: DRUMMER YAYA DIALLO BRINGS THE HEALING ENERGY. —page 22 LEFT: FANS CHEER THE KNIGHTS TO ANOTHER VICTORY. COVER PHOTO BY GEOFF OLIVER BUGBEE PHOTO AT LEFT BY BRIAN TIRPAK spring 2009 3 from THE EDITOR Harmonic convergence OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY DR. JOSEPH J. MCGOWAN President WHB EN ELLARMINE MAGAZINE CONTRIBUTOR KATIE KELTY WENT TO The Concord archives in search of a flashback story for this issue’s “Concord Classic,” she DR. -

Olson Medical Clinic Services Que Locura Noticiero Univ

TVetc_35 9/2/09 1:46 PM Page 6 SATURDAY ** PRIME TIME ** SEPTEMBER 5 TUESDAY ** AFTERNOON ** SEPTEMBER 8 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> The Lawrence Welk Show ‘‘When Guy Lombardo As Time Goes Keeping Up May to Last of the The Red Green Soundstage ‘‘Billy Idol’’ Rocker Austin City Limits ‘‘Foo Fighters’’ Globe Trekker Classic furniture in KUSD d V (11:30) Sesame Barney & Friends The Berenstain Between the Lions Wishbone ‘‘Mixed Dragon Tales (S) Arthur (S) (EI) WordGirl ‘‘Mr. Big; The Electric Fetch! With Ruff Cyberchase Nightly Business KUSD d V the Carnival Comes’’; ‘‘Baby and His Royal By Appearances December Summer Wine Show ‘‘Comrade Billy Idol performs his hits to a Grammy Award-winning group Foo Hong Kong; tribal handicrafts of the Street (S) (EI) (N) (S) (EI) Bears (S) (S) (EI) Breeds’’ (S) (EI) Book Ends’’ (S) (EI) Company (S) (EI) Ruffman (S) (EI) ‘‘Codename: Icky’’ Report (N) (S) Elephant Walk’’; ‘‘Tiger Rag.’’ Canadians (S) Harold’’ (S) packed house. (S) Fighters perform. (S) Makonde tribes. (S) KTIV f X News (N) (S) Days of our Lives (N) (S) Little House on the Prairie ‘‘The Faith Little House on the Prairie ‘‘The King Is Extra (N) (S) The Ellen DeGeneres Show (Season News (N) (S) NBC Nightly News News (N) (S) The Insider (N) Law & Order: Criminal Intent A Law & Order A firefighter and his Law & Order: Special Victims News (N) (S) Saturday Night Live Anne Hathaway; the Killers. -

A 040909 Breeze Thursday

Post Comments, share Views, read Blogs on CaPe-Coral-daily-Breeze.Com Ballgame Local teams go head to head in CAPE CORAL Bud Roth tourney DAILY BREEZE — SPORTS WEATHER: Mostly Sunny • Tonight: Mostly Clear • Saturday: Partly Cloudy — 2A cape-coral-daily-breeze.com Vol. 48, No. 89 Friday, April 17, 2009 50 cents Cape man guilty on all counts in ’05 shooting death “I’m very pleased with the verdict. This is a tough case. Jurors deliberate for nearly 4 hours It was very emotional for the jurors, but I think it was the right decision given the evidence and the facts of the By CONNOR HOLMES tery with a deadly weapon. in the arm by co-defendant Anibal case.” [email protected] Gaphoor has been convicted as Morales; Jose Reyes-Garcia, who Dave Gaphoor embraced his a principle in the 2005 shooting was shot in the arm by Morales; — Assistant State Attorney Andrew Marcus mother, removed his coat and let death of Jose Gomez, 25, which and Salatiel Vasquez, who was the bailiff take his fingerprints after occurred during an armed robbery beaten with a tire iron. At the tail end of a three-day made the right decision. a 12-person Lee County jury found in which Gaphoor took part. The jury returned from approxi- trial and years of preparation by “I’m very pleased with the ver- him guilty Thursday of first-degree Several others were injured, mately three hours and 45 minutes state and defense attorneys, dict,” he said Thursday. “This is a felony murder, two counts of including Rigoberto Vasquez, who of deliberations at 8 p.m. -

06 SM 3/1 (TV Guide)

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, March 1, 2005 Monday Evening March 7, 2005 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Extreme Makeover Ho Boss Swap SuperNanny Local Local Jimmy K KBSH/CBS Still Stand Listen Up Raymond 2 1/2 Men CSI Miami Local Late Show Late Late KSNK/NBC Fear Factor The Contender Local Tonight Show Conan FOX American Idol 24 Local Local Local Local Local Local Cable Channels A&E Airline Gotti Gotti Caesars 24/7 Crossing Jordan Airline AMC Rocky 2 Rocky 2 ANIM Pet Star Who Get's The Dog Animal Cops - San Fr Pet Star Who Get's The Dog CNN Paula Zahn Now Larry King Live Newsnight Lou Dobbs Larry King Norton TV DISC Monster House Monster Garage American Chopper Monster House Monster Garage DISN Disney Movie: TBA Raven Sis Bug Juice Lizzie Boy Meets Even E! THS Love is in the Heir Howard Stern SNL ESPN Championship Week Championship Week ESPN2 Championship Week Fastbreak Streetball FAM Whose Lin Whose Lin Whose Lin Whose Lin Whose Lin Whose Lin The 700 Club Funniest Funniest FX Sleeping With The Enemy Fear Factor Sleeping With The Enemy HGTV Homes Ac Dec Cents Kit Trends To Sell Desg Fina Dsgnr Fin Dime D Travis Homes Ac Dec Cents HIST UFO Files Digging For The Truth Deep Sea Detectives Investigating History UFO Files LIFE Determination of Death Lies My Mother Told How Clea How Clea Nanny Golden MTV RW/RR Room Raiders Wanna? Listings: NICK SpongeBo Drake Full Hous Full Hous Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes SCI Stargate SG-1 Stargate SG-1 Battlestar Galactica Inferno SPIKE CSI WWE Raw WWE Raw -

2004 Crossroads in Cultural Studies FIFTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE

2004 Crossroads in Cultural Studies FIFTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE June 25-28, 2004 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign www.crossroads2004.org CONFERENCE ORGANIZERS The Fifth International Crossroads in Cultural Studies is organized by the College of Communications, the Institute of Communications Research and the Interdisciplinary Program in Cultural Studies and Interpretive Research at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in conjunction with the Association for Cultural Studies. CONFERENCE PROGRAM This conference program and abstract book was compiled and produced by the conference organizing committee. The program was printed by the Office of Printing Services at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. CONFERENCE SPONSORS Asian American Studies · Blackwell Publishers · Center for Advanced Study Center for Democracy in a Multiracial Society · Center for Global Studies College of Communications · Educational Policy Studies · Ford Foundation Gender & Women’s Studies · International Affairs Illinois Program for Research in the Humanities Institute of Communications Research · Kinesiology · Latin American Studies Latino/a Studies · Russian East European Center · Sociology South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies · Speech Communication Sage Publications · Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory ii General information Table of Contents Preface from the chair ...................................................... iv Preface from the ACS president ........................................ v Conference organizers.....................................................