Jordi Savall Talks About Grief, Memory and Building Bridges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jordi Savall, Viol Frank Mcguire, Bodhrán

Friday, February 26, 2016, 8pm First Congregational Church Berkeley RADICAL: The Natural World Jordi Savall , viol Frank McGuire , bodhrán MAN & NATURE MUSICAL HUMORS & LANDSCAPES In the English, Irish, Scottish and American traditions PROGRAM The Caledonia Set The Humours of Scariff Traditional Irish Archibald MacDonald of Keppoch Traditional Irish The Musical Priest / Scotch Mary Captain Simon Fraser (1816 Collection) Caledonia’s Wail for Niel Gow Traditional Irish Sackow’s Jig (Treble Viol) The Musicall Humors Tobias Hume, 1605 A Souldiers March Captaine Hume’s Pavin A Souldiers Galliard Harke, harke Good againe A Souldiers Resolution (Bass Viol, the Lute Tunning) Flowers of Edinburg Traditional Scottish Lady Mary Hay’s Scots Measure Shetland Tune Da Slockit Light Reel The Flowers of Edinburg Niel Gow (1727–1807) Lament for the Death of his Second Wife Fisher’s Hornpipe Tomas Anderson Peter’s Peerie Boat (Treble Viol) INTERMISSION The Bells Alfonso Ferrabosco II Coranto Thomas Ford Why not here John Playford La Cloche & Saraband (Bass Viol, Lyra way, the First tuning) The Donegal Set Traditional Irish The Tuttle’s Reel Turlough O’Carolan Planxty Irwin O’Neill, Chicago 1903 Alexander’s Hornpipe Jimmy Holme’s Favorite Donegal tradition Gusty’s Frolics (Treble Viol) THE LORD MOIRA’S SET Ryan’s Collection (Boston, 1883) Regents Rant Crabs in the Skillet—Slow jig The Sword dance Lord Moira Lord Moira’s Hornpipe (Bass Viol Lyra-way: the Bagpipes tuning) IRISH LANDSCAPES The Morning Dew The Hills of Ireland Apples in the Winter The Rocky Road to Dublin The Kid on the Mountain Morrison’s Jig (Treble Viol) This performance is made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsors Will and Linda Schieber. -

Artistes Per La Pau” Dins Del Coro Barroco De Andalucia (Sevilla), Històrica

Jordi Savall, violes de gamba & direcció Jordi Savall és una de les personali- tats musicals més polivalents de la seva generació. Fa més de cinquanta anys que dóna a conèixer al món meravelles musicals abandonades en la foscor de la indiferència i de l’oblit. Dedicat a la recerca d’aquestes músiques antigues, les llegeix i les interpreta amb la seva viola de gamba, o com a director. Les seves activitats com a concertista, pe- dagog, investigador i creador de nous projectes, tant musicals com culturals, Lluís Vilamajó, tenor & direcció de ponsable de la direcció artística, amb el situen entre els principals artífexs del amb Montserrat Figueras, varen ser la Jove Capella Reial de Catalunya Lambert Climent i Carlos Mena del fenomen de revalorització de la música investits “Artistes per la Pau” dins del Coro Barroco de Andalucia (Sevilla), històrica. És fundador, juntament amb programa “Ambaixadors de bona volun- Nascut a Barcelona, inicià els seus y del Coro Vozes de “Al Ayre Español” Montserrat Figueras, dels grups musi- tat” de la UNESCO. estudis musicals a l’Escolania de Mont- (Zaragoza). Paral·lelament ha començat cals Hespèrion XXI (1974), La Capella serrat, i després els continuà al Conser- el projecte FONICS per a joves can- Reial de Catalunya (1987) i Le Concert La seva fecunda carrera musical ha vatori Municipal Superior de Música de tants, i és director artístic del Coro de la des Nations (1989) amb els que explora estat mereixedora de les més altes dis- Barcelona. Actualment és membre de la Orquesta Ciudad de Granada i del Joven i crea un univers d’emocions i de be- tincions nacionals i internacionals, d’en- Capella Reial de Catalunya dirigida per Coro de Andalucía. -

Download Booklet

THE GUERRA MANUSCRIPT Volume 4 17th Century Secular Spanish Vocal Music Hernández • Fernández-Rueda • Arias Fernández Ars Atlántica • Manuel Vilas, Harp and Director The Guerra Manuscript, Vol. 4 The Guerra Manuscript, Volume 4 17th Century Secular Spanish Vocal Music 1 Anon: Qué dulcemente canta 3:19 2 Juan Hidalgo (1614-1685): ¿Qué quiere Amor? 2:43 This fourth volume in the complete recording of the Orléans (first wife of the Spanish king Charles II) to 3 Anon: Hermosa tortolilla 3:40 vocal works found in the Guerra Manuscript contains a Madrid. He then visited Italy in 1680-81, probably as 4 Anon: Poco sabe de Filis 3:04 further twenty pieces of music. This manuscript is, in part of his duties as a member of the queen’s staff. On 5 Juan Hidalgo: Con la pasión amorosa 2:59 my opinion, the leading source of tonos humanos to his death, Guerra bequeathed his library to his son, Juan 6 José Marín (c.1619-1699): Filis, el miedo ha de ser 5:09 have survived to the present day and a document of Alfonso de Guerra, who also inherited many of his titles fundamental importance in the history of Spanish music. and privileges. An inventory of this library, dated 1738, 7 Juan Hidalgo: ¡Ay que sí, ay que no! 4:50 Broadly speaking, tonos humanos are secular songs, has survived and includes the books that Juan Alfonso 8 Anon: Si descubro mi dolor 4:00 some of which are drawn from seventeenth- and was left by his father. The collection was sold to the 9 Anon: Culpas son Nise hermosa 3:44 eighteenth-century Spanish theatrical works. -

Radio 3 Listings for 1 – 7 February 2020 Page 1

Radio 3 Listings for 1 – 7 February 2020 Page 1 of 12 SATURDAY 01 FEBRUARY 2020 05:21 AM Meta4 Francesco Cavalli (1602-1676) Khatia Buniatishvili (piano) SAT 01:00 Through the Night (m000ds6c) Lauda Jerusalem (psalm 147, 'How good it is to sing praises to Bach from Barcelona our God') Concerto Palatino SAT 12:30 New Generation Artists (m000dz9y) Lutenist Thomas Dunford plays Bach in the Palau de la Música NGA 20th anniversary celebrations Catalana, Barcelona. Catriona Young presents. 05:31 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) Fiona Talkington continues the 20th anniversary celebrations of 01:01 AM Ballade for piano No.1 (Op.23) in G minor the Radio 3 New Generation Artists scheme with further Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Hinko Haas (piano) performances by some of the scheme's alumni, including bass- Cello Suite No. 5 in C minor, BWV 1011 baritone Jonathan Lemalu, the Apollon Musagète Quartet, Thomas Dunford (lute) 05:41 AM pianist Louis Schwizgebel and percussionist Colin Currie. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) 01:25 AM Violin Sonata in C major, K303 Music includes: Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Tai Murray (violin), Shai Wosner (piano) c.12.50pm Cello Suite No. 3 in C, BWV 1009 Tchaikovsky: String Quartet No 1 (1st movement) Thomas Dunford (lute) 05:51 AM Apollon Musagète Quartet Claude Debussy (1862-1918), Pierre Louys (author) 01:47 AM Chansons de Bilitis - 3 melodies for voice & piano (1897) c.1.05pm John Dowland (1563-1626) Paula Hoffman (mezzo soprano), Lars David Nilsson (piano) Saint-Saëns: Piano Concerto No 5 (Egyptian) Come Again, Sweet Love Doth Now Invite Louis Schwizgebel (piano) Thomas Dunford (vocalist), Thomas Dunford (lute) 06:00 AM BBC Symphony Orchestra Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Martyn Brabbins (conductor) 01:51 AM Sextet for piano and strings in D major, Op 110 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Wu Han (piano), Philip Setzer (violin), Nokuthula Ngwenyama c.1.35pm Prelude, from Cello Suite No. -

Jordi Savall and Carlos Núñez and Friends Thursday, May 10, 2018 at 8:00Pm This Is the 834Thconcert in Koerner Hall

Jordi Savall and Carlos Núñez and Friends Thursday, May 10, 2018 at 8:00pm This is the 834thconcert in Koerner Hall Carlos Núñez, Galician bagpipes, pastoral pipes (Baroque ancestor of the Irish Uilleann pipes) & whistles Pancho Álvarez, Viola Caipira (Brazilian guitar of Baroque origin) Xurxo Núñez, percussions, tambourins & Galician pandeiros Andrew Lawrence-King, Irish harp & psalterium Frank McGuire, bodhran Jordi Savall, treble viol (by Nicholas Chapuis, Paris c. 1750) lyra-viol (bass viol by Pelegrino Zanetti, Venice 1553) & direction PROGRAM – CELTIC UNIVERSE Introduction: Air for the Bagpipes The Caledonia Set Traditional Irish: Archibald MacDonald of Keppoch Traditional Irish: The Musical Priest / Scotch Mary Captain Simon Fraser (1816 Collection): Caledonia's Wail for Niel Gow Traditional Irish: Sackow's Jig Celtic Universe in Galicia Alalá En Querer Maruxiña Diferencias sobre la Gayta The Lord Moira Set Dan R. MacDonald: Abergeldie Castle Strathspey Traditional Scottish: Regents Rant - Lord Moira Ryan’s Mammoth Collection (Boston, 1883): Lord Moira's Hornpipe Flowers of Edinburg Charlie Hunter: The Hills of Lorne Reel: The Flowers of Edinburg Niel Gow: Lament for the Death of his Second Wife Fisher’s Hornpipe Tomas Anderson: Peter’s Peerie Boat INTERMISSION The Donegal Set Traditional Irish: The Tuttle’s Reel Traditional Scottish: Lady Mary Hay’s Scots Measure Turlough O’Carolan: Carolan’s Farewell Donegal tradition: Gusty’s Frolics Jimmy Holme’s Favorite Carolan’s Harp Anonymous Irish: Try if it is in Tune: Feeghan Geleash -

Jordi Savall Hespèrion XX-XXI, La Capella Reial De Catalunya, Le Concert Des Nations

DISCOGRAPHY Jordi Savall Hespèrion XX-XXI, La Capella Reial de Catalunya, Le Concert des Nations 1968 1. Songs of Andalusia (Andalusian Songs) Victoria de Los Angeles & Barcelona Ars Musicae - Dir. Enric Gispert HMV “Angel Series” SAN 194 [LP] 2. Del Romànic al Renaixement - Le Moyen-Age Catalan, de l’art roman à la renaissance Ars musicae de Barcelone - Gispert Edigsa AMC 10/051 [LP] 1970 3. Recercadas del “Tratado de Glosas” Jordi Savall, Genoveva Gálvez, Sergi Casademunt Hispavox HHS 7 [LP] 1971 4. De Guillaume Dufay à Josquin Des Prés - Chansons d’amour du 15e siècle Ensemble d’Instruments anciens “Ricercare” de Zurich - Dir. Michel Piguet Erato STU 70661 [LP] 1972 5. Music for guitar and harpsichord John Williams / Rafael Puyana / Jordi Savall Columbia “CBS Masterworks” M 31194 [LP] 6. Ludwig Senfl Deutsche Lieder Ricercare - Ensemble für Alte Musik, Zurich - Dir. Michel Piguet EMI/Electrola “Reflexe” 1C 063 30 104 [LP] 7. Telemann - Suite & Concerto J. Savall, M. Piguet, Orchestre de chambre Jean-François Paillard - Dir. J.-F. Paillard Erato STU 70711 [LP] 1973 8. Musik des Trecento um Jacopo da Bologna Ricercare-Ensemble für Alte Musik, Zurich - Dir. Michel Piguet EMI/Electrola “Reflexe” 1C 063 30 111 [LP] 1 9. Die Instrumentalvariation in der Spanischen Renaissancemusik Ricercare-Ensemble für Alte Musik, Zurich - Dir. Michel Piguet / Jordi Savall EMI/Electrola “Reflexe” 1C 063 30 116 [LP] 10. Praetorius - Auswalh aus Terpsichore Ricercare- Ensemble für Alte Musik, Zürich - Dir. Michel Piguet EMI/Electrola “Reflexe” 1C 063 30 117 [LP] 11. Jean-Baptiste Lully: Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, Comédie-Ballet (1670) LWV 43 Various singers & La Petite Bande – Dir. -

Download Program Notes

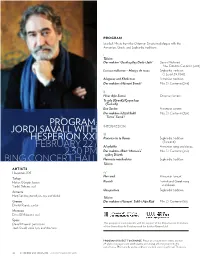

PROGRAM Istanbul: Music from the Ottoman Empire in dialogue with the Armenian, Greek, and Sephardic traditions I Taksim Der makām “Uzzäl uşūleş Darb-i feth” Dervis Mehmed, Mss. Dimitrie Cantemir (209) La rosa enflorece – Maciço de rosas Sephardic tradition (I. Levy I.59, III.41) Alagyeaz and Khnki tsar Armenian tradition Der makām-ı Hüseynī Semâ’î Mss. D. Cantemir (268) II Hisar Ağir Semai Ottoman lament Ta xyla (Greek)/Çeçen kızı (Turkish) Ene Sarére Armenian lament Der makām-ı Uzzäl Sakîl Mss. D. Cantemir (324) “Turna” Semâ’î PROGRAM: INTERMISSION JORDI SAVALL WITH III Paxarico tu te llamas Sephardic tradition HESPÈRION XXI (Sarajevo) FEBRUARY 22 / Al aylukhs Armenian song and dance Der makām-ı Räst “Murass’a” Mss. D. Cantemir (214) 2:30 PM uşūleş Düyek BING CONCERT HALL Hermoza muchachica Sephardic tradition Taksim ARTISTS Hespèrion XXI IV Hov arek Armenian lament Turkey Hakan Güngör, kanun Koniali Turkish and Greek song Yurdal Tokcan, oud and dance Sephardic tradition Armenia Una pastora Haïg Sarikouyoumdjian, ney and duduk Taksim Greece Der makām-ı Hüseynī Sakīl-i Ağa Riżā Mss. D. Cantemir (89) Dimitri Psonis, santur Morocco Driss El Maloumi, oud Spain David Mayoral, percussion This program is made possible with the support of the Departament de Cultura Jordi Savall, vielle, lyra, and direction of the Generalitat de Catalunya and the Institut Ramon Llull. PROGRAM SUBJECT TO CHANGE. Please be considerate of others and turn off all phones, pagers, and watch alarms, and unwrap all lozenges prior to the performance. Photography and recording of any kind are not permitted. Thank you. 42 STANFORD LIVE MAGAZINE JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2015 JORDI SAVALL Savall and Ms. -

18 SEMANA DE MÚSICA ANTIGUA DE ESTELLA 1987 Iglesia De Santa Clara

18 SEMANA DE MÚSICA ANTIGUA DE ESTELLA 1987 Iglesia de Santa Clara José Miguel Moreno, vihuela, laúd Renacimiento español, francés e inglés Trío La Stravaganza, flautas, clave, viola de gamba Frescobaldi, Cima, Marcello, Telemann, Marais, Hotteterre, Morel (ss. XVI-XVIII) Claudi Arimany, flauta Jordi Reguant, clave Música virtuosística para flauta de J. S. Bach y sus alumnos Quinteto “Música Humana”, canto, violín, viola de gamba, tiorba, arpa, guitarra barroca Música inglesa, italiana y española del s. XVII Quinteto “La Folía”, flauta, violines, bajo continuo Mancini, Loeillet, J. S. Bach, Telemann, Corelli, Naudot (ss. XVII-XVIII) Quinteto vocal “Gregor” Polifonía del Siglo de Oro española. Música colonial de las catedrales de América. 19 SEMANA DE MÚSICA ANTIGUA DE ESTELLA 1988 Iglesia de Santa Clara Romá Escalas, flauta de pico Josep Borrás, fagot Albert Romaní, clave Génesis y proyección del lenguaje barroco instrumental Iñaki Fresán, barítono Albert Romaní, clave Arias italianas del XVI al XVIII Couperin, Rameau, Padre Soler, B. de Astorga (ss. XVII-XVIII) Quinteto “Turba Musici”, voz, viento, cuerda, percusión, teclado Los trovadores y los monasterios (ss. XII-XIV) Cuarteto “Diatessaron”, flautas, oboe, viola de gamba, clave Música italiana e inglesa del s. XVII Jordi Savall, viola de gamba Tobias Hume y J. S. Bach Sebastián Durón, grupo vocal e instrumental Música española de los siglos XVI y XVII Coro Samaniego Gregoriano, polifonía de los siglos XIII-XVIII 20 SEMANA DE MÚSICA ANTIGUA DE ESTELLA 1989 Iglesia de Santa Clara Antiqua -

Jordi Savall and Hespèrion XXI with Carlos Núñez in Seattle

MUSIC Jordi Savall and Hespèrion SEATTLE XXI with Carlos Núñez in Sat, May 05, 2018 Seattle 7:30 pm Venue Seattle First Baptist Church, 1111 Harvard Ave, Seattle, WA 98122 View map Phone: 206-325-7066 Admission This event is currently sold out. Please fill out this form to be placed on the wait list More information Early Music Seattle Credits Presented by Early Music Seattle Gamba virtuoso Jordi Savall and musicians from Hespèrion XXI are joined by Galician bagpiper Carlos Núñez to celebrate the lively music of Celtic culture. Jordi Savall celebrates the Celtic musical traditions by playing with the great galician bagpiper Carlos Núñez, who will be accompanied by musicians Pancho Álvarez and Xurxo Núñez, and with Savall’s usual accomplices: the famous harpist Andrew Lawrence-King with the Irish harp or the psaltery, and Frank McGuire, one of today best players of bodhran. Together they trace the route of Celtic migration, from Ireland to Iberia, through music. JORDI SAVALL For more than 50 years, Jordi Savall, one of the most versatile musical personalities of his generation, has rescued musical gems from the obscurity of neglect and oblivion and given them back for all to enjoy. A tireless researcher into early music, he interprets and performs the repertory both as a gambist and a conductor. His activities as a concert performer, teacher, researcher and creator of new musical and cultural projects have made him a leading figure in the reappraisal of historical music. Together with Montserrat Figueras, he founded the ensembles Hespèrion XXI (1974), La Capella Reial de Catalunya (1987) and Le Concert des Nations (1989), with whom he explores and creates a world of emotion and beauty shared with millions of early music enthusiasts around Embassy of Spain – Cultural Office | 2801 16th Street, NW, Washington, D.C. -

THE CONCERT of NATIONS: MUSIC, POLITICAL THOUGHT and DIPLOMACY in EUROPE, 1600S-1800S

THE CONCERT OF NATIONS: MUSIC, POLITICAL THOUGHT AND DIPLOMACY IN EUROPE, 1600s-1800s A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Damien Gérard Mahiet August 2011 © 2011 Damien Gérard Mahiet THE CONCERT OF NATIONS: MUSIC, POLITICAL THOUGHT AND DIPLOMACY IN EUROPE, 1600s-1800s Damien Gérard Mahiet, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 Musical category, political concept, and political myth, the Concert of nations emerged within 16th- and 17th-century court culture. While the phrase may not have entered the political vocabulary before the end of the 18th century, the representation of nations in sonorous and visual ensembles is contemporary to the institution of the modern state and the first developments of the international system. As a musical category, the Concert of nations encompasses various genres— ballet, dance suite, opera, and symphony. It engages musicians in making commonplaces, converting ad hoc representations into shared realities, and uses multivalent forms that imply, rather than articulate political meaning. The Nutcracker, the ballet by Tchaikovsky, Vsevolozhsky, Petipa and Ivanov, illustrates the playful re- composition of semiotic systems and political thought within a work; the music of the battle scene (Act I) sets into question the equating of harmony with peace, even while the ballet des nations (Act II) culminates in a conventional choreography of international concord (Chapter I). Chapter II similarly demonstrates how composers and librettists directly contributed to the conceptual elaboration of the Concert of nations. Two works, composed near the close of the War of Polish Succession (1733-38), illustrate opposite constructions of national character and conflict resolution: Schleicht, spielende Wellen, und murmelt gelinde (BWV 206) by Johann Sebastian Bach (librettist unknown), and Les Sauvages by Jean-Philippe Rameau and Louis Fuzelier. -

L'arte Salva L'arte

Cover 2011 20-10-2011 13:33 Pagina 1 L’Arte salva L’Arte Festival Internazionale di Musica e Arte Sacra ROMA E VATICANO Via Paolo VI, 29 (piazza San Pietro) 00193 Roma www.festivalmusicaeartesacra.net www.fondazionepromusicaeartesacra.net L’Arte salva L’Arte FESTIVAL INTERNAZIONALE DI MUSICA E ARTE SACRA DECIMA EDIZIONE ROMA E VATICANO, 26-30 OTTOBRE E 5-6 NOVEMBRE 2011 Redazione Ruth Prucker Fotografie Riccardo Musacchio, Flavio Ianniello Grafica Digitalialab, Roma Stampa Grafica Giorgetti, Roma I contenuti letterari e le fotografie sono di proprietà della Fondazione Pro Musica e Arte Sacra. Tutti i diritti sono riservati. © Fondazione Pro Musica e Arte Sacra 2011 ISBN 978-88-89505-33-5 2011 Camera di Commercio Industria Artigianato e Agricoltura di Roma Via de’ Burrò 147 – 00186 Roma www.camcom.it Finito di stampare nel mese di ottobre 2011 per l’Editore CCIAA di Roma presso la Tipografia Grafica Giorgetti via di Cervara- 00155 Roma GLI ENTI PATROCINANTI CON L'ADESIONE DEL PRESIDENTE DELLA REPUBBLICA ARTE, MECENATISMO E TURISMO CULTURALE PER L’URBE ECONILPATROCINIO È sufficiente scorrere, anche velocemente, ciò che in meno di dieci anni la Fondazione pro Musica e Arte Sacra ha messo in atto, per rendersi conto che è possibile fare cose che nel mondo dell’arte sacra, del suo restauro e della sua conservazione si davano per impossibili o per improbabili solo pochi anni fa. Il segreto è semplice: basta che ci siano uomini e donne, che, sicuri e forti di un valore importante come del Senato della Repubblica quello dell’arte sacra, convincano altri uomini e donne a collaborare e a salvare questa tradizione con at- della Camera dei Deputati ti importanti di mecenatismo. -

![Arianna Savall/Petter Udland Johansen Hirundo Maris Chants Du Sud Et Du Nord [Cantos Del Sur Y Del Norte]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2203/arianna-savall-petter-udland-johansen-hirundo-maris-chants-du-sud-et-du-nord-cantos-del-sur-y-del-norte-3052203.webp)

Arianna Savall/Petter Udland Johansen Hirundo Maris Chants Du Sud Et Du Nord [Cantos Del Sur Y Del Norte]

Arianna Savall/Petter Udland Johansen Hirundo Maris Chants du Sud et du Nord [Cantos del Sur y del Norte] Arianna Savall: voz, arpa gótica, triple arpa italiana; Petter Udland Johansen: voz, violin Hardanger, mandolina; Sveinung Lilleheier: guitarra, Dobro, voz; Miquel Àngel Cordero: contrabajo, voz; David Mayoral: percusión, voz. ECM New Series 2227 CD 6025 278 4395 (7) Salida: Junio 2012 El debut de Arianna Savall como líder en las New Series sigue a su distinguidas contribuciones a “Nuove musiche” de Rolf Lislevand’s y a “Lijnen” de Helena Tulve, sensual música antigua la primera obra, tonificante composición contemporánea la segunda. En ambos géneros Arianna ha demostrado ser una cantante carismática. Ahora llega “Hirundo Maris”, que con sus frescas texturas instrumentales inicia una nueva senda. Savall y el co-líder del grupo, Petter Udland Johansen describen su proyecto como un viaje que enlaza al Mediterráneo con el Mar del Norte. Hirundo Maris significa “golondrina” en latín y, como el vuelo de esa ave, el quinteto –en parte un ensamble de música antigua, en parte un grupo de música folclórica, recoge elementos de corrientes musicales desde Noruega hasta Cataluña, añade sus propias canciones, creadas al vuelo, y se zambulle para bucear bajo la superficie de las cosas. Más o menos en el centro de todo eso están el sonido de las brillantes arpas de Arianna y el arrullo del violín Hardanger de Johansen. Cuando se suman los colores de la mandolina y los más inesperados del Dobro (que no se escucha muy a menudo fuera del bluegrass), se envía un mensaje sobre la universalidad de la canción, así como sobre los viajes transatlánticos de las antiguas baladas… Savall y Johansen han dado forma a su banda con un brillante y variado conjunto de timbres, moderados por la cristalina voz de Savall, bien dotada para interpretar tanto canciones del norte como del sur.