A Double Edged Sword

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abbreviations

Abbreviations CPH Chinhoyi Provincial Hospital DMO District Medical officer GMO Government Medical Officer HMO Hospital Medical Officer HCH Harare Central Hospital HRH Human Resources for Health HSB Health Service Board HTF Health Transition Fund MoHCC Ministry of Health and Child Care OI Opportunistic Infections PCN Primary Care Nurse RGN Registered General Nurse SCN State Certified Nurse SHO Senior House Officer SRMO Senior Resident Medical Officer WHO World Health Organization WISN Workload Indicators of Staffing Needs UBH United Bulawayo Hospital ZIMASSET Zimbabwe Agenda for Sustainable Socio Economic Transformation Written and Compiled by: Bernard Nkala (Health Service Board) Bernard Gotora (Health Service Board) Funded by: GoZ i Acknowledgements The Health Service Board (HSB) and Ministry of Health and Child Care (MoHCC) would like to extend its gratitude and appreciation to all representatives of various organisations and individuals who made invaluable contributions before, during and after the implementation of WISN in Zimbabwe. We are grateful to the Health Development Fund and Treasury for funding the WISN Study in Zimbabwe. The study was successful owing to the technical expertise and guidance provided by WHO Country Office working with the Afro Regional Technical Team. The WISN in Zimbabwe would not have been a success without the guidance and direction of the Steering Committee for implementing the WISN study in Zimbabwe and the WISN Expert Work- ing Group who developed the data collection tools. The Technical Taskforce immensely contribut- ed in coming with the WISN results for the studied facilities. The contribution of Messrs Nkala Bernard and Gotora Bernard in writing this study report would not go unnoticed. -

Bulawayo City Mpilo Central Hospital

Province District Name of Site Bulawayo Bulawayo City E. F. Watson Clinic Bulawayo Bulawayo City Mpilo Central Hospital Bulawayo Bulawayo City Nkulumane Clinic Bulawayo Bulawayo City United Bulawayo Hospital Manicaland Buhera Birchenough Bridge Hospital Manicaland Buhera Murambinda Mission Hospital Manicaland Chipinge Chipinge District Hospital Manicaland Makoni Rusape District Hospital Manicaland Mutare Mutare Provincial Hospital Manicaland Mutasa Bonda Mission Hospital Manicaland Mutasa Hauna District Hospital Harare Chitungwiza Chitungwiza Central Hospital Harare Chitungwiza CITIMED Clinic Masvingo Chiredzi Chikombedzi Mission Hospital Masvingo Chiredzi Chiredzi District Hospital Masvingo Chivi Chivi District Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chimombe Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chinyika Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chitando Rural Health Centre Masvingo Gutu Gutu Mission Hospital Masvingo Gutu Gutu Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Mukaro Mission Hospital Masvingo Masvingo Masvingo Provincial Hospital Masvingo Masvingo Morgenster Mission Hospital Masvingo Mwenezi Matibi Mission Hospital Masvingo Mwenezi Neshuro District Hospital Masvingo Zaka Musiso Mission Hospital Masvingo Zaka Ndanga District Hospital Matabeleland South Beitbridge Beitbridge District Hospital Matabeleland South Gwanda Gwanda Provincial Hospital Matabeleland South Insiza Filabusi District Hospital Matabeleland South Mangwe Plumtree District Hospital Matabeleland South Mangwe St Annes Mission Hospital (Brunapeg) Matabeleland South Matobo Maphisa District Hospital Matabeleland South Umzingwane Esigodini District Hospital Midlands Gokwe South Gokwe South District Hospital Midlands Gweru Gweru Provincial Hospital Midlands Kwekwe Kwekwe General Hospital Midlands Kwekwe Silobela District Hospital Midlands Mberengwa Mberengwa District Hospital . -

Zimbabwean Government Gazette, 8Th February, 1985 103

GOVERNMENT?‘GAZETTE Published by Autry £ x | Vol. LX, No, 8 f 8th FEBRUARY,1985 Price 30c 3 General Notice 92 of 1985, The service to operate as follows— Route 1: , 262] > * ROAD MOTOR TRANSPORTATION ACT [CHAPTER (a) depart Bulawayo Monday 9 am., arrive Beitbridge 3.15 p.m.; Applications in Connexion with Road Service Permits (b) depart Bulawayo. Friday 5 pm., arrive Beitbridge as 11.15 p.m. _ IN terms of subsection(4) of section 7 of the- Road Moter ‘(c) depart BulawayoB Saturday 10 am., arrive Beitbridge Transportation Act [Chapter 262], notice is hereby given that 13 ‘p. the applications detailed in the Schedule, for the issue or | (d) depart eitbridge Tuesday 8.40 a.m., astive Bulawayo amendment of road service its, have been received for the 3.30 p. consideration of the Control}ér of Road Motor Transportation. (e) depart Beitbridge Saturday 3.40 am., arrive Bulawayo Any personwishing to Object to any such application must - a.m} ‘lodge with the Controlle? of Road Motor Transportation, (f) depart’ Beitbridge Sunday 9.40 am., arrive Bulawayo P.O. Box 8332, Causeway— 4.30 p.m, ~ . : eg. (a) a notice; in writing, of his intention fo object, so as to - Route 2: No change. _* teach the Controller'ss office not later than the Ist March, Cc. R. BHana. ’ 1985; 0/284/84. Permit: 23891."Motor-omnibus. Passenger-capacity: (b) his objection and the groiinds therefor, on form R.M.T, 24, tozether with two copies thereof, so as to reach the Route: Bulawayo - Zyishavane - _Mashava - Masvingo - Controller’s office not later than the 22nd March, 1985. -

Nyasa Clandestine Migration Through Southern Rhodesia Into the Union of South Africa: 1920S – 1950S

Settling in Motion: Nyasa Clandestine Migration through Southern Rhodesia into the Union of South Africa: 1920s – 1950s Anusa Daimon Centre for Africa Studies University of the Free State Bloemfontein, South Africa Abstract Illegal African migration into South Africa is not uniquely a post-apartheid phenomenon. It has its antecedents in the colonial/apartheid period. The South Africa colonial economy relied heavily on cheap African labour from both within and outside the Union. Most foreign migrant labourers came from the then Nyasaland (Malawi) and Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique) through official channels of the Witwatersrand Native Labour Association (WNLA). WNLA was active throughout the Southern Africa and competed for the same labour resource with other regional supranational ‘native’ labour recruitment agencies, providing various incentives to lure and transport potential employees to its bustling South African gold and diamond mining industry. However, not all migrant labourers found their way through formal WNLA channels. Using archival material from repositories in Harare (Zimbabwe), Zomba (Malawi), Grahamstown (South Africa), London and Oxford (UK), the article casts light on illicit migration mainly by Malawian labourers (Nyasas) through Southern Rhodesia into South Africa between the 1920s and 1950s. It argues that many transient Nyasas subverted the inhibitive WNLA contractual obligations by clandestinely migrating independently into the Union. They also exploited the labour recruitment infrastructure used by the state and labour bureaus to swiftly move across Southern Rhodesia. In essence, Nyasas settled in motion, using Southern Rhodesia as a stepping-stone or springboard en-route to the more lucrative Union of South Africa. An appreciation of such informal migration opens up space for creating a more comprehensive historiography of labour migration in Southern Africa. -

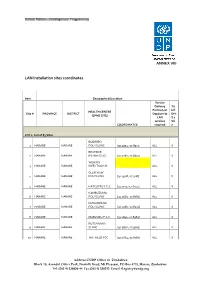

LAN Installation Sites Coordinates

ANNEX VIII LAN Installation sites coordinates Item Geographical/Location Service Delivery Tic Points (List k if HEALTH CENTRE Site # PROVINCE DISTRICT Dept/umits DHI (EPMS SITE) LAN S 2 services Sit COORDINATES required e LOT 1: List of 83 Sites BUDIRIRO 1 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9354,-17.8912] ALL X BEATRICE 2 HARARE HARARE RD.INFECTIO [31.0282,-17.8601] ALL X WILKINS 3 HARARE HARARE INFECTIOUS H ALL X GLEN VIEW 4 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9508,-17.908] ALL X 5 HARARE HARARE HATCLIFFE P.C.C. [31.1075,-17.6974] ALL X KAMBUZUMA 6 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9683,-17.8581] ALL X KUWADZANA 7 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9285,-17.8323] ALL X 8 HARARE HARARE MABVUKU P.C.C. [31.1841,-17.8389] ALL X RUTSANANA 9 HARARE HARARE CLINIC [30.9861,-17.9065] ALL X 10 HARARE HARARE HATFIELD PCC [31.0864,-17.8787] ALL X Address UNDP Office in Zimbabwe Block 10, Arundel Office Park, Norfolk Road, Mt Pleasant, PO Box 4775, Harare, Zimbabwe Tel: (263 4) 338836-44 Fax:(263 4) 338292 Email: [email protected] NEWLANDS 11 HARARE HARARE CLINIC ALL X SEKE SOUTH 12 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0763,-18.0314] ALL X SEKE NORTH 13 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0943,-18.0152] ALL X 14 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ST.MARYS CLINIC [31.0427,-17.9947] ALL X 15 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ZENGEZA CLINIC [31.0582,-18.0066] ALL X CHITUNGWIZA CENTRAL 16 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA HOSPITAL [31.0628,-18.0176] ALL X HARARE CENTRAL 17 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [31.0128,-17.8609] ALL X PARIRENYATWA CENTRAL 18 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [30.0433,-17.8122] ALL X MURAMBINDA [31.65555953980,- 19 MANICALAND -

Thesis for Sethi Sibanda (1019068).Pdf

School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies An assessment of the impacts of climate and land use/cover changes on wetland extent within Mzingwane catchment, Zimbabwe. BY SETHI SIBANDA (1019068) Submitted to the Faculty of Science, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Geography and Environmental Science) Supervisors: Prof. Fethi Ahmed Prof. Stefan Grab June 2018 i DECLARATION I declare that this work is my own original work and has not been previously submitted to obtain any academic qualification. Data and information obtained from published and unpublished work of others have been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is herein provided. Signature: ------------------------------------ Date: ----------------------------------------- i DEDICATION To my late father with love ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisors, Prof. Fethi Ahmed and Prof. Stefan Grab for their exceptional academic guidance, encouragement, and support throughout the study. Truly, the experience was academically rewarding. I also appreciate the financial support I received from Prof. Fethi Ahmed, without such support this study was not going to be possible. I also acknowledge various institutions that provided data for the study. I am greatly indebted to my husband and family who have been a pillar of strength throughout the study. Lastly, I would like to extend my gratitude to all my friends and colleagues from Lupane State University whose moral and academic support contributed to the success of this study. iii ABSTRACT Wetlands ecosystems are amongst the most diverse and valuable environments which provide a number of goods and services pertinent to human and natural systems functioning yet they are increasingly threatened by anthropogenic and climatic changes. -

TREATMENT SITES Southern Africa HIV and AIDS Information LISTED by PROVINCE and AREA Dissemination Service

ARV TREATMENT SITES Southern Africa HIV and AIDS Information LISTED BY PROVINCE AND AREA Dissemination Service MASVINGO · Bulilima: Plumtree District hospital: · Bikita: Silveira Mission Hospital: Tel: (038)324 Tel. (019) 2291; 2661-3 · Chiredzi: Hippo Valley Estates Clinic: · Gwanda: Gwanda OI Clinic: Tel: (084)22661-3: Tel: (031)2264 - Mangwe: St. Annes Brunapeg: · Chiredzi: Colin Saunders Hosp. Tel: (082) 361/466 AN HIV/AIDS Tel: (033)6387:6255 · Kezi-Matobo: Tshelanyemba Mission Hosp: · Chiredzi: Chiredzi District Hosp.: Tel: (033) Tel: (082) 254 · Gutu: Gutu Mission Hosp: · Maphisa District Hosp: Tel. (082) 244 Tel: (030)2323:2313:2631:3229 · Masvingo: Morgenster Mission Hosp: MIDLANDS Tel: (039)262123 · Chivhu General Hosp: Tel: (056):2644:2351 TREATMENT - Masvingo Provincial Hosp: · Chirumhanzu: Muvonde Hosp: Tel: (032)346 Tel: (039)263358/9; 263360 · Mvuma: St Theresas Mission Hosp: - Masvingo: Mukurira Memorial Private Hospital: Tel: (0308)208/373 Tel. (039) 264919 · Gweru: Gweru Provincial Hospital: ROADMAP FOR · Mwenezi: Matibi Mission Hospital: Tel. (0517) 323 Tel: (054) 221301:221108 · Zaka: Musiso Mission Hosp: · Gweru: Gweru City Hospital: Tel: (054) Tel: (034)2286:2322:2327/8 221301:221108 - Gweru: Mkoba 1 Polyclinic, Tel. MATEBELELAND NORTH - Gweru: Lower Gweru Rural Health Clinic: · Hwange: St Patricks Mission Hosp: Tel: (054) 227023 Tel: (081)34316-7 · Kwekwe: Kwekwe General Hospital: ZIMBABWE · Lupane: St Lukes Mission Hosp: Tel: (055)22333/7:24828/31 Tel: (0898)362:549:349 · Mberengwa: Mnene Mission Hospital: · Tsholotsho: Tsholotsho District Hosp: Tel. (0518) 352/3 Tel: (0878) 397/216/299 A guide for accessing anti- PRIVATE DOCTORS retroviral treatment in MATEBELELAND SOUTH For a list of private doctors who have special Zimbabwe: what it is, where · Beitbridge: Beitbridge District Hosp: training in ARV treatment and counselling, ask Tel.(086) 22496-8 your own doctor or contact SAfAIDS. -

Zimbabwe Situation Report - 30 April 2017

UNICEF Zimbabwe Situation Report - 30 April 2017 Zimbabwe Humanitarian Situation Report © UNICEF 2016/T.Mukwazhi Situation Report #13 – 30 April 2017 SITUATION IN NUMBERS TION IN NUMBERS Highlights 859 people Displaced by flooding in In response to the floods which hit parts of the country, UNICEF Tsholotsho Sipepa Camp provided teaching and learning materials, water, sanitation, and (DCP, February 2017) hygiene (WASH) and child protection services to over 3,000 people in the flood-affected districts. As of 31 March 2017, over 3,300 children aged 0-59 months had 3,312 been treated for severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in 20 drought Children aged 0-59 months with SAM affected districts. from 20 drought affected districts were Since the start of the year, more than 2,200 suspected typhoid admitted and treated in the IMAM cases have been reported in the country out of which 64 have been program as of 31 March 2017 laboratory confirmed and six typhoid related deaths reported. (DHIS, April 2017) UNICEF continues to support emergency preparedness and response through critical lifesaving health and WASH interventions 2,209 in flood affected areas and identified diarrheal disease hot spots. Cumulative typhoid cases comprising During the reporting period, UNICEF received US$ 2 million from 2,145 suspected, 64 laboratory confirmed the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and 6 reported deaths through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to (MOHCC, April 2017) expand its WASH programme interventions in 10 drought-affected -

The Political Ecology of Poverty Alleviation in Zimbabwe's Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources CAMPFIRE) B

Geoforum 33 2002) 1±14 www.elsevier.com/locate/geoforum The political ecology of poverty alleviation in Zimbabwe's Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources CAMPFIRE) B. Ikubolajeh Logan a, William G. Moseley b a Department of Geography, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602-2502, USA b Department of Geography, Northern Illinois University, Dekalb, IL 60115-2854, USA Received 13 November 2000; in revised form 25 June 2001 Abstract The CAMPFIRE program in Zimbabwe is one of a `new breed' of strategies designed to tackle environmental management at the grassroots level. CAMPFIRE aims to help rural communities to manage their resources, especially wildlife, for their own local development. The program's central objective is to alleviate rural poverty by giving rural communities autonomy over resource management and to demonstrate to them that wildlife is not necessarily a hindrance to arable agriculture, ``but a resource that could be managed and `cultivated' to provide income and food''. In this paper, we assess two important elements of CAMPFIRE: poverty alleviation and local empowerment and comment on the program's performance in achieving these highly interconnected objectives. We analyze the program's achievements in poverty alleviation by exploring tenurial patterns, resource ownership and the allocation of proceeds from resource exploitation; and its progress in local empowerment by examining its administrative and decision making structures. We conclude that the program cannot eectively achieve the goal of poverty alleviation without ®rst addressing the administrative and legal structures that underlie the country's political ecology. Ó 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Political ecology; Poverty alleviation; Community-empowerment; CAMPFIRE 1. -

Matebeleland South

HWANGE WEST Constituency Profile MATEBELELAND SOUTH Hwange West has been stripped of some areas scene, the area was flooded with tourists who Matebeleland South province is predominantly rural. The Ndebele, Venda and the Kalanga people that now constitute Hwange Central. Hwange contributed to national and individual revenue are found in this area. This province is one of the most under developed provinces in Zimbabwe. The West is comprised of Pandamatema, Matesti, generation. The income derived from tourists people feel they have been neglected by the government with regards to the provision of education Ndlovu, Bethesda and Kazungula. Hwange has not trickled down to improve the lives of and health as well as road infrastructure. Voting patterns in this province have been pro-opposition West is not suitable for human habitation due people in this constituency. People have and this can be possibly explained by the memories of Gukurahundi which may still be fresh in the to the wild life in the area. Hwange National devised ways to earn incomes through fishing minds of many. Game Park is found in this constituency. The and poaching. Tourist related trade such as place is arid, hot and crop farming is made making and selling crafts are some of the ways impossible by the presence of wild life that residents use to earn incomes. destroys crops. Recreational parks are situated in this constituency. Before Zimbabwe's REGISTERED VOTERS image was tarnished on the international 22965 Year Candidate Political Number Of Votes Party 2000 Jelous Sansole MDC 15132 Spiwe Mafuwa ZANU PF 2445 2005 Jelous Sansole MDC 10415 Spiwe Mafuwa ZANU PF 4899 SUPPORTING DEMOCRATIC ELECTIONS 218 219 SUPPORTING DEMOCRATIC ELECTIONS BULILIMA WEST Constituency Profile Constituency Profile BULILIMA EAST Bulilima West is made up of Dombodema, residents' incomes. -

Alluvial Aquifers in the Mzingwane Catchment: Their Distribution, Properties, Current Usage and Potential Expansion

Physics and Chemistry of the Earth 31 (2006) 988–994 www.elsevier.com/locate/pce Alluvial aquifers in the Mzingwane catchment: Their distribution, properties, current usage and potential expansion William Moyce a,*, Pride Mangeya a, Richard Owen a,d, David Love b,c a Department of Geology, University of Zimbabwe, P.O. Box MP167, Mt. Pleasant, Harare, Zimbabwe b WaterNet, P.O. Box MP600, Mt. Pleasant, Harare, Zimbabwe c ICRISAT Bulawayo, Matopos Research Station, P.O. Box 776, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe d Minerals Resources Centre, University of Zimbabwe, P.O. Box MP167, Mt. Pleasant, Harare, Zimbabwe Abstract The Mzingwane River is a sand filled channel, with extensive alluvial aquifers distributed along its banks and bed in the lower catch- ment. LandSat TM imagery was used to identify alluvial deposits for potential groundwater resources for irrigation development. On the false colour composite band 3, band 4 and band 5 (FCC 345) the alluvial deposits stand out as white and dense actively growing veg- etation stands out as green making it possible to mark out the lateral extent of the saturated alluvial plain deposits using the riverine fringe and vegetation . The alluvial aquifers form ribbon shaped aquifers extending along the channel and reaching over 20 km in length in some localities and are enhanced at lithological boundaries. These alluvial aquifers extend laterally outside the active channel, and individual alluvial aquifers have been measured with area ranging from 45 ha to 723 ha in the channels and 75 ha to 2196 ha on the plains. The alluvial aquifers are more pronounced in the Lower Mzingwane, where the slopes are gentler and allow for more sediment accumulation. -

Zimbabwe Livelihood Zone Profiles. December 2010

Zimbabwe Livelihoods Zone VAC ZIMBABWE Profiles Vulnerability Assessment Committee 15 February 2010 The Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVac) is Chaired by the Food and Nutrition Council (FNC) which is housed at the Scientific Industrial Research and Developing Council (SIRDC), Harare, Zimbabwe. Acknowledgements The Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVac) would like to express its appreciation for the financial, technical and logistical support that the following agencies provided towards the data collection, analysis and writing-up of the Revised Livelihoods profiles for Zimbabwe; Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation Development and Mechanizations’ Department of Agricultural Extension Services (AGRITEX) Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare’s Department of Social Welfare Ministry of Finance’s Central Statistical Office (CSO) Ministry of Education’s Curriculum Development Ministry of Transport’s Department of Meteorological Services United Nations’ World Food Programme (WFP) United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) United Nations’ Office of Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) World Vision (WV) OXFAM ACTIONAID Save the Children United Kingdom (SC-UK) Southern Africa Development Community Regional Vulnerability Assessment Committee (RVAC) United States of America International Development Agency (USAID) Department for International Development (DFID) The European Commission (EC) FEG (The Food Economy Group) The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWSNET) The revision