Note to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dracula Film Adaptations

DRACULA IN THE DARK DRACULA IN THE DARK The Dracula Film Adaptations JAMES CRAIG HOLTE Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, Number 73 Donald Palumbo, Series Adviser GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Recent Titles in Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy Robbe-Grillet and the Fantastic: A Collection of Essays Virginia Harger-Grinling and Tony Chadwick, editors The Dystopian Impulse in Modern Literature: Fiction as Social Criticism M. Keith Booker The Company of Camelot: Arthurian Characters in Romance and Fantasy Charlotte Spivack and Roberta Lynne Staples Science Fiction Fandom Joe Sanders, editor Philip K. Dick: Contemporary Critical Interpretations Samuel J. Umland, editor Lord Dunsany: Master of the Anglo-Irish Imagination S. T. Joshi Modes of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Twelfth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Robert A. Latham and Robert A. Collins, editors Functions of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Thirteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Joe Sanders, editor Cosmic Engineers: A Study of Hard Science Fiction Gary Westfahl The Fantastic Sublime: Romanticism and Transcendence in Nineteenth-Century Children’s Fantasy Literature David Sandner Visions of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Fifteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Allienne R. Becker, editor The Dark Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Ninth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts C. W. Sullivan III, editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Holte, James Craig. Dracula in the dark : the Dracula film adaptations / James Craig Holte. p. cm.—(Contributions to the study of science fiction and fantasy, ISSN 0193–6875 ; no. -

The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature

From Upyr’ to Vampir: The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature Dorian Townsend Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Languages and Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of New South Wales May 2011 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Townsend First name: Dorian Other name/s: Aleksandra PhD, Russian Studies Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: School: Languages and Linguistics Faculty: Arts and Social Sciences Title: From Upyr’ to Vampir: The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) The Slavic vampire myth traces back to pre-Orthodox folk belief, serving both as an explanation of death and as the physical embodiment of the tragedies exacted on the community. The symbol’s broad ability to personify tragic events created a versatile system of imagery that transcended its folkloric derivations into the realm of Russian literature, becoming a constant literary device from eighteenth century to post-Soviet fiction. The vampire’s literary usage arose during and after the reign of Catherine the Great and continued into each politically turbulent time that followed. The authors examined in this thesis, Afanasiev, Gogol, Bulgakov, and Lukyanenko, each depicted the issues and internal turmoil experienced in Russia during their respective times. By employing the common mythos of the vampire, the issues suggested within the literature are presented indirectly to the readers giving literary life to pressing societal dilemmas. The purpose of this thesis is to ascertain the vampire’s function within Russian literary societal criticism by first identifying the shifts in imagery in the selected Russian vampiric works, then examining how the shifts relate to the societal changes of the different time periods. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO American Gothic Fiction: Vampire

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE American Gothic Fiction: Vampire Romances Final thesis Brno 2012 Supervisor: Author: PhDr. Irena Přibylová, Ph.D. Mgr. Jitka Čápová Declaration I hereby declare that I have written this final thesis myself and that all the sources I have used are listed in the bibliography section. Hradec Králové 13 August 2012 …………………………………………… Mgr. Jitka Čápová Acknowledgements: I would like to thank to PhDr. Irena Přibylová, Ph.D. for her time, patience and valuable advice. I would also like to thank to my family for their support. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Theory ................................................................................................................................................. 2 2.1 Gothic ................................................................................................................................................ 3 2.2 Romance ............................................................................................................................................ 5 2.3 Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................... 9 3. Analysis ............................................................................................................................................ -

“We Have Always Been Vampires”: Systems of Fear and Desire And

1 “WE HAVE ALWAYS BEEN VAMPIRES”: SYSTEMS OF FEAR AND DESIRE AND TENTACULAR NETWORKS IN VAMPIRE LITERATURE A thesis presented by Matthew Cote to the Department of English Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts degree in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April, 2017 2 “WE HAVE ALWAYS BEEN VAMPIRES”: SYSTEMS OF FEAR AND DESIRE AND TENTACULAR NETWORKS IN VAMPIRE LITERATURE by Matthew Cote ABSTRACT OF THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2017 3 ABSTRACT The vampire has proven itself immortal as both a subject of literary and critical interest and as a feature of its monstrous Otherness. Its timeless tale is one that belongs to Donna Haraway’s category of “finnicky and disruptive” stories—an ongoing cultural narrative of our world “that doesn’t know how to finish.” Using the critical works of Donna Haraway and Clifford Siskin to delineate two key terms—networks and systems, respectively— this project frames the vampire Other as a recurring and sublimated reflection of the individuated subject. By examining Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, H.P. Lovecraft’s short story “The Shunned House,” and, finally, Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend, this project will explore the “tentacularity” of the vampire network, or what Haraway calls “life lived along lines.” This project considers how literary epistemologies figure the subject/other binary within a continuously expanding ontological scope regarding the vampire’s threat to subjective networks: Carmilla explores the local and interpersonal; Dracula contends with provincial infection through information and knowledge; “The Shunned House” confronts fungal and interspecies anxieties; and, finally, I Am Legend recognizes global, immunological realities. -

The Figure of the Vampire Has Been Inextricably Linked to the History Of

ENTERTEXT From Pathology to Invisibility: The Discourse of Ageing in Vampire Fiction Author: Marta Miquel-Baldellou Source: EnterText, “Special Issue on Ageing and Fiction,” 12 (2014): 95-114. Abstract A diachronic analysis of the way the literary vampire has been characterised from the Victorian era to the contemporary period underlines a clear evolution which seems especially relevant from the perspective of ageing studies. One of the permanent features characterising the fictional vampire from its origins to its contemporary manifestations in literature is precisely the vampire’s disaffection with the effects of ageing despite its actual old age. Nonetheless, even though the vampire no longer ages in appearance, the way it has been presented has significantly evolved from a remarkable aged appearance during the Victorian period through Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1872) or Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) to outstanding youth in Anne Rice’s An Interview with the Vampire (1976), adolescence in Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight (2005), and even childhood in John Ajvide Lindquist’s Let The Right One In (2007), thus underlining a significant process of rejuvenation despite the vampire’s acknowledged old age. This paper shows how the representations of the vampire in the arts, mainly literature and cinema, reflect a shift from the embodiment of pathology to the invisibility, or the denial, of old age. 95 | The Discourse of Ageing in Vampire Fiction From Pathology to Invisibility: The Discourse of Ageing in Vampire Fiction Marta Miquel-Baldellou Ageing and vampire fiction The figure of the vampire has been inextricably linked to the history of humanity since ancient and classical times as an embodiment of fear, otherness, evil and the abject. -

Vampire Figures in Anglo-American Literature And

Jihočeská univerzita v Českých Budějovicích Pedagogická fakulta Katedra anglistiky Diplomová práce Vampire Figures in Anglo-American Literature and Their Metamorphosis from Freaks to Heroes Charakteristika a příčiny posunu vnímání postav upírů v Anglo-americké literatuře, tj. literární přeměna negativní zrůdy v hrdinskou postavu vypracovala: Alžběta Němcová vedoucí práce: Mgr. Linda Kocmichová České Budějovice 2014 Prohlašuji, že svoji diplomovou práci jsem vypracovala samostatně pouze s použitím pramenů a literatury uvedených v seznamu citované literatury. Prohlašuji, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. v platném znění souhlasím se zveřejněním své diplomové práce, a to v nezkrácené podobě elektronickou cestou ve veřejně přístupné části databáze STAG provozované Jihočeskou univerzitou v Českých Budějovicích na jejích internetových stránkách, a to se zachováním mého autorského práva k odevzdanému textu této kvalifikační práce. Souhlasím dále s tím, aby toutéž elektronickou cestou byly v souladu s uvedeným ustanovením zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. zveřejněny posudky školitele a oponentů práce i záznam o průběhu a výsledku obhajoby kvalifikační práce. Rovněž souhlasím s porovnáním textu mé kvalifikační práce s databází kvalifikačních prací Theses.cz provozovanou Národním registrem vysokoškolských kvalifikačních prací a systémem na odhalování plagiátů. V Českých Budějovicích dne 24. 6. 2014 Alžběta Němcová Acknowledgements I would hereby like to thank to my diploma thesis supervisor, Mgr. Linda Kocmichová, for her valuable advice, patience and supervision regarding the compilation of this diploma thesis. Poděkování Chtěla bych poděkovat vedoucí mé diplomové práce, Mgr. Lindě Kocmichové, za její cenné rady, trpělivost a pomoc při psaní této diplomové práce. Abstract The aim of this work is to outline the development of a vampire portrayal in Anglo- American Literature. -

The Vampire Archetype and the Steampunk Vamp Carina Maxfield

LiteraturaSubverting e Ética: the experiências Canon: The de leitura Vampire em contexto Archetype de ensino and the Steampunk Vamp Alexandra Isabel Lobo da Silva Lopes Carina Maxfield Dissertação de Mestrado em Estudos Portugueses Dissertação de Mestrado em Línguas, Literaturas e Culturas Versão corrigida e melhorada após a sua defesa pública. Especialização em Estudos Ingleses e Norte-Americanos Setembro, 2011 Novembro 2016 LiteraturaSubverting e Ética: the experiências Canon: The de leitura Vampire em contexto Archetype de ensino and the Steampunk Vamp Alexandra Isabel Lobo da Silva Lopes Carina Maxfield Dissertação de Mestrado em Estudos Portugueses Dissertação de Mestrado em Línguas, Literaturas e Culturas Versão corrigida e melhorada após a sua defesa pública. Especialização em Estudos Ingleses e Norte-Americanos Setembro, 2011 Novembro 2016 Dissertação apresentada para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Línguas, Literaturas e Culturas, realizada sob a orientação científica de Professora Doutora Iolanda Ramos. Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere thanks to Professor Iolanda Ramos for her time and patience in helping me complete this dissertation. I would also like to thank the school and several public libraries around Lisbon for lending me the space to complete my research. Finally, I would like to thank all of my friends, Vítor Arnaut, and my loving family for their complete physical and moral support through this at times challenging moment in my life. Subverter o Cânone: O Arquétipo do Vampiro e o ‘Steampunk Vamp’ Carina Maxfield Resumo Esta dissertação tem como objectivo analisar os diferentes modos em que o arquétipo do vampirismo se tem modificado das normas convencionais e como prevaleceu. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction Is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper aligrunent can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Xnfonnation Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL; FEMALE AUTHORSHIP AND THE LITERARY VAMPIRE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor o f Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kathy S. -

Anne Rice Writes Difficult Books, and I Simply Didn't Have

UG_2013_05 Vampires Don’t Sparkle: Vampires Outside the Romance Genre My fascination with vampires began when I was eleven, and discovered Anne Rice. I was a world-weary almost-teen with a reading ability way beyond standard for my grade level, and I was definitely ready for her. I read The Vampire Lestat first, even though it’s technically the second in the series. It didn’t matter. I was hooked. Anne Rice is a sensual writer and she made vampires sexy. I hadn’t read Dracula yet so I had no idea what literary baggage vampires might carry with them. As far as I was concerned they were beautiful, deadly, occasionally amoral and frequently religious, and totally fascinating. Then Twilight came out, and the world of vampire literature changed forever. At the risk of sounding really hipster, I probably read Twilight before you. I happened to be looking for vampire books just as it arrived, so I snatched it up and read it immediately. I realized almost immediately that it was total crap and didn’t compare in any way to Anne Rice. Sparkly vampires? Seriously? Even Rice, who writes pretty sympathetic undead characters, manages to make them menacing at least half the time. The Cullens just aren’t scary. This was the point where I gave up and read Dracula, which set the canon in 1897 for every vampire book that followed. It’s an important book to read if you like vampires, or horror, or fantasy. I read it and all of a sudden my perception of vampires changed drastically. -

This Is the Final Version of the Program As of February 27, 2011. Any Changes Made After This Point Will Be Reflected in the Errata Sheet

This is the final version of the program as of February 27, 2011. Any changes made after this point will be reflected in the errata sheet. ******* Tuesday, March 15, 2011 7:00 p.m. Pre‐Conference Party President’s Suite Open to all. ******* Wednesday, March 16, 2011 2:30‐3:30 p.m. Pre‐Opening Refreshment Capri ******* Wednesday, March 16, 2011 3:30‐4:15 p.m. Opening Ceremony Capri Host: Donald E. Morse, Conference Chair Welcome from the President: Jim Casey Opening Panel: Science Fiction and Romantic Comedy: Just Not That Into You Capri Moderator: Jim Casey Terry Bisson James Patrick Kelly John Kessel Connie Willis ******* Wednesday, March 16, 2011 4:30‐6:00 p.m. 1. (PCS) Fame, Fandom, and Filk: Fans and the Consumption of Fantastical Music Pine Chair: Elizabeth Guzik California State University, Long Beach Out of this World: Intersections between Science Fiction, Conspiracy Culture and the Carnivalesque Aisling Blackmore University of Western Australia “I’m your biggest fan, I’ll follow you until you love me”: Fame, the Fantastic and Fandom in the Haus of Gaga Daryl Ritchot Simon Fraser University Pop Culture on Blend: Parody and Comedy Song in the Filk Community Rebecca Testerman Bowling Green State University 2. (SF) Biotechnologies and Biochauvinisms Oak Chair: Neil Easterbrook TCU Biotechnology and Neoliberalism in The Windup Girl Sherryl Vint Brock University Neither Red nor Green: Fungal Biochauvinism in Science Fiction Roby Duncan California State University, Dominguez Hills Daniel Luboff Independent Scholar Ecofeminism, the Environment, -

Magic, Trick-Work, and Illusion in the Vampire Plays

MAGIC, TRICK-WORK, AND ILLUSION IN THE VAMPIRE PLAYS by THOMAS LEONARD COLWIN, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Accepted Dean^f the Graduate School August, 1987 30I c 1987 Thomas Leonard Colwln ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to Professor Forrest Newlin for his direction of this dissertation and to the other members of my committee. Professors Kenneth Ketner, Richard Weaver, Michael Gerlach and Michael Stoune for their helpful criticisms. I also wish to acknowledge the invaluable assistance and support of my friend, Esther Lichti. Finally, I wish to express my deep gratitude to my wife, Jane, for her tireless support, helpful criticism, and unending hard work in the preparation of this study. 11 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION: MAGIC IN THE THEATRE 1 II. THEATRICAL ILLUSION 10 III. MAGICAL ILLUSION 24 IV. ILLUSION VERSUS ILLUSION 35 V. TRICK-WORK IN THE VAMPIRE PLAYS 44 VI. CONCLUSION: MAGIC FOR THE THEATRE 87 ENDNOTES 92 BIBLIOGRAPHY 102 APPENDIX 110 111 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION: MAGIC IN THE THEATRE Magic has always held a place in the world of the theatre. Within the whole of dramatic literature there exists a body of plays which all contain elements of the magical, the mystical, the supernatural. Some of these plays have only overtones of the paranormal, but a great many more call for seemingly magical or supernatural events to be realized on the stage. As far back as the fifth century, B.C., the Greeks used devices like the mechane, or crane, to give the illusion of Perseus on his flying horse or of various gods descending from the heavens. -

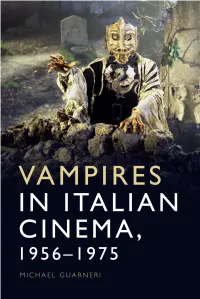

9781474458139 Vampires in It

VAMPIRES IN ITALIAN CINEMA, 1956–1975 66352_Guarneri.indd352_Guarneri.indd i 225/04/205/04/20 110:030:03 AAMM 66352_Guarneri.indd352_Guarneri.indd iiii 225/04/205/04/20 110:030:03 AAMM VAMPIRES IN ITALIAN CINEMA, 1956–1975 Michael Guarneri 66352_Guarneri.indd352_Guarneri.indd iiiiii 225/04/205/04/20 110:030:03 AAMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Michael Guarneri, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 10/12.5 pt Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5811 5 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5813 9 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5814 6 (epub) The right of Michael Guarneri to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 66352_Guarneri.indd352_Guarneri.indd iivv 225/04/205/04/20 110:030:03 AAMM CONTENTS Figures and tables vi Acknowledgements viii Introduction 1 PART I THE INDUSTRIAL CONTEXT 1. The Italian fi lm industry (1945–1985) 23 2. Italian vampire cinema (1956–1975) 41 PART II VAMPIRE SEX AND VAMPIRE GENDER 3.