What Stoker Saw: an Introduction To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyberpunking a Library

Cyberpunking a Library Collection assessment and collection Leanna Jantzi, Neil MacDonald, Samantha Sinanan LIBR 580 Instructor: Simon Neame April 8, 2010 “A year here and he still dreamed of cyberspace, hope fading nightly. All the speed he took, all the turns he’d taken and the corners he’d cut in Night City, and he’d still see the matrix in his sleep, bright lattices of logic unfolding across that colorless void.” – Neuromancer, William Gibson 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Description of Subject ....................................................................................................................................... 3 History of Cyberpunk .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Themes and Common Motifs....................................................................................................................................... 3 Key subject headings and Call number range ....................................................................................................... 4 Description of Library and Community ..................................................................................................... -

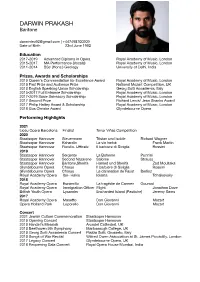

Darwin Prakash CV July 2021

DARWIN PRAKASH Baritone [email protected] | +447498700209 Date of Birth 23rd June 1993 Education 2017-2019 Advanced Diploma in Opera Royal Academy of Music, London 2015-2017 MA Performance (Vocals) Royal Academy of Music, London 2011-2014 BSc (Hons.) Geology University of Delhi, India Prizes, Awards and Scholarships 2019 Queen's Commendation for Excellence Award Royal Academy of Music, London 2019 First Prize and Audience Prize National Mozart Competition, UK 2018 English Speaking Union Scholarship Georg Solti Accademia, Italy 2015-2017 Full Entrance Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017-2019 Susie Sainsbury Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017 Second Prize Richard Lewis/ Jean Shanks Award 2017 Philip Hattey Award & Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2016 Gus Christie Award Glyndebourne Opera Performing Highlights 2021 Liceu Opera Barcelona Finalist Tenor Viñas Competition 2020 Staatsoper Hannover Steuermann Tristan und Isolde Richard Wagner Staatsoper Hannover Kaherdin Le vin herbé Frank Martin Staatsoper Hannover Fiorello, Ufficale Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini 2019 Staatsoper Hannover Sergente La Boheme Puccini Staatsoper Hannover Second Nazarene Salome Strauss Staatsoper Hannover Baritone,Sherifa Hamed und Sherifa Zad Moultaka Glyndebourne Opera Chorus Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini Glyndebourne Opera Chorus La damnation de Faust Berlioz Royal Academy Opera Ibn- Hakia Iolanta Tchaikovsky 2018 Royal Academy Opera Escamillo La tragédie de Carmen Gounod Royal Academy Opera Immigration Officer Flight Jonathan Dove British Youth Opera Lysander Enchanted Island (Pastiche) Jeremy Sams 2017 Royal Academy Opera Masetto Don Giovanni Mozart Opera Holland Park Leporello Don Giovanni Mozart Concert 2021 Jewish Culture Commemoration Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Opening Concert Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Handel's Messiah Arundel Cathedral, UK 2018 Beethoven 9th Symphony Marlborough College, UK 2018 Georg Solti Accademia Concert Piazza Solti, Grosseto, Italy 2018 Songs of War Recital Wilfred Owen Association at St. -

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S. Pinafore Friday, May 5, 2017, 7:30 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. Albert Bergeret, artistic director in H.M.S. Pinafore or The Lass that Loved a Sailor Libretto by Sir William S. Gilbert | Music by Sir Arthur Sullivan First performed at the Opera Comique, London, on May 25, 1878 Directed and conducted by Albert Bergeret Choreography by Bill Fabis Scenic design by Albère | Costume design by Gail Wofford Lighting design by Benjamin Weill Production Stage Manager: Emily C. Rolston* Assistant Stage Manager: Annette Dieli DRAMATIS PERSONAE The Rt. Hon. Sir Joseph Porter, K.C.B. (First Lord of the Admiralty) James Mills* Captain Corcoran (Commanding H.M.S. Pinafore) David Auxier* Ralph Rackstraw (Able Seaman) Daniel Greenwood* Dick Deadeye (Able Seaman) Louis Dall’Ava* Bill Bobstay (Boatswain’s Mate) David Wannen* Bob Becket (Carpenter’s Mate) Jason Whitfield Josephine (The Captain’s Daughter) Kate Bass* Cousin Hebe Victoria Devany* Little Buttercup (Mrs. Cripps, a Portsmouth Bumboat Woman) Angela Christine Smith* Sergeant of Marines Michael Connolly* ENSEMBLE OF SAILORS, FIRST LORD’S SISTERS, COUSINS, AND AUNTS Brooke Collins*, Michael Galante, Merrill Grant*, Andy Herr*, Sarah Hutchison*, Hannah Kurth*, Lance Olds*, Jennifer Piacenti*, Chris-Ian Sanchez*, Cameron Smith, Sarah Caldwell Smith*, Laura Sudduth*, and Matthew Wages* Scene: Quarterdeck of H.M.S. Pinafore *The actors and stage managers employed in this production are members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. -

The Sexual Vampire

Hugvísindasvið Vampires in Literature The attraction of horror and the vampire in early and modern fiction Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Magndís Huld Sigmarsdóttir Maí 2011 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enska Vampires in literature The attraction of horror and the vampire in early and modern fiction Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Magndís Huld Sigmarsdóttir Kt.: 190882-4469 Leiðbeinandi: Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir Maí 2011 1 2 Summary Monsters are a big part of the horror genre whose main purpose is to invoke fear in its reader. Horror gives the reader the chance to escape from his everyday life, into the world of excitement and fantasy, and experience the relief which follows when the horror has ended. Vampires belong to the literary tradition of horror and started out as monsters of pure evil that preyed on the innocent. Count Dracula, from Bram Stoker‘s novel Dracula (1897), is an example of an evil being which belongs to the class of the ―old‖ vampire. Religious fears and the control of the church were much of what contributed to the terrors which the old vampire conveyed. Count Dracula as an example of the old vampire was a demonic creature who has strayed away from Gods grace and could not even bear to look at religious symbols such as the crucifix. The image of the literary vampire has changed with time and in the latter part of the 20th century it has lost most of its monstrosity and religious connotations. The vampire‘s popular image is now more of a misunderstood troubled soul who battles its inner urges to harm others, this type being the ―new‖ vampire. -

Irish Gothic Fiction

THE ‘If the Gothic emerges in the shadows cast by modernity and its pasts, Ireland proved EME an unhappy haunting ground for the new genre. In this incisive study, Jarlath Killeen shows how the struggle of the Anglican establishment between competing myths of civility and barbarism in eighteenth-century Ireland defined itself repeatedly in terms R The Emergence of of the excesses of Gothic form.’ GENCE Luke Gibbons, National University of Ireland (Maynooth), author of Gaelic Gothic ‘A work of passion and precision which explains why and how Ireland has been not only a background site but also a major imaginative source of Gothic writing. IRISH GOTHIC Jarlath Killeen moves well beyond narrowly political readings of Irish Gothic by OF IRISH GOTHIC using the form as a way of narrating the history of the Anglican faith in Ireland. He reintroduces many forgotten old books into the debate, thereby making some of the more familiar texts seem suddenly strange and definitely troubling. With FICTION his characteristic blend of intellectual audacity and scholarly rigour, he reminds us that each text from previous centuries was written at the mercy of its immediate moment as a crucial intervention in a developing debate – and by this brilliant HIST ORY, O RIGI NS,THE ORIES historicising of the material he indicates a way forward for Gothic amidst the ruins of post-Tiger Ireland.’ Declan Kiberd, University of Notre Dame Provides a new account of the emergence of Irish Gothic fiction in the mid-eighteenth century FI This new study provides a robustly theorised and thoroughly historicised account of CTI the beginnings of Irish Gothic fiction, maps the theoretical terrain covered by other critics, and puts forward a new history of the emergence of the genre in Ireland. -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

The Dracula Film Adaptations

DRACULA IN THE DARK DRACULA IN THE DARK The Dracula Film Adaptations JAMES CRAIG HOLTE Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, Number 73 Donald Palumbo, Series Adviser GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Recent Titles in Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy Robbe-Grillet and the Fantastic: A Collection of Essays Virginia Harger-Grinling and Tony Chadwick, editors The Dystopian Impulse in Modern Literature: Fiction as Social Criticism M. Keith Booker The Company of Camelot: Arthurian Characters in Romance and Fantasy Charlotte Spivack and Roberta Lynne Staples Science Fiction Fandom Joe Sanders, editor Philip K. Dick: Contemporary Critical Interpretations Samuel J. Umland, editor Lord Dunsany: Master of the Anglo-Irish Imagination S. T. Joshi Modes of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Twelfth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Robert A. Latham and Robert A. Collins, editors Functions of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Thirteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Joe Sanders, editor Cosmic Engineers: A Study of Hard Science Fiction Gary Westfahl The Fantastic Sublime: Romanticism and Transcendence in Nineteenth-Century Children’s Fantasy Literature David Sandner Visions of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Fifteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Allienne R. Becker, editor The Dark Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Ninth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts C. W. Sullivan III, editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Holte, James Craig. Dracula in the dark : the Dracula film adaptations / James Craig Holte. p. cm.—(Contributions to the study of science fiction and fantasy, ISSN 0193–6875 ; no. -

Marschner Heinrich

MARSCHNER HEINRICH Compositore tedesco (Zittau, 16 agosto 1795 – Hannover, 16 dicembre 1861) 1 Annoverato fra i maggiori compositori europei della sua epoca, nonché degno rivale in campo operistico di Carl Maria von Weber, strinse amicizia con i maggiori musicisti del tempo, fra cui Ludwig van Beethoven e Felix Mendelssohn Bartoldy. Dopo gli studi fatti a Lipsia ed a Praga con Tomášek e dopo essersi introdotto nel mondo musicale viennese, fu nominato maestro di cappella a Bratislava e successivamente divenne il direttore dei teatri dell'opera di Dresda e Lipsia; fu quindi ad Hannover nel periodo 1830-59, per dirigere la cappella di corte. Marschner fu fondamentalmente un compositore teatrale, fra le opere che gli conferirono maggior fama si annoverano: Der Vampyr (1828), Der templar und die Jüdin (1829) e un'opera di gusto popolare e leggendario, come è nel suo stile, intitolata Hans Heiling (1833), la quale ha alcune analogie con L'olandese volante di Richard Wagner. Caratteristica dell'arte di Marschner sono: la ricerca (nel melodramma) di soggetti soprannaturali caratteristici di quel senso puramente romantico di "orrore dilettevole", ma anche cavallereschi e soprattutto popolari, resi attraverso una ritmica incalzante, una vasta coloritura dei timbri orchestrali e con l'ausilio di numerosi leitmotiv e fili conduttori musicali. Non mancano inoltre nella sua produzione numerosi Lieder, due quartetti per pianoforte e ben sette trii per pianoforte particolarmente apprezzati da Robert Schumann. 2 3 HANS HEILING Tipo: Opera romantica in un prologo e tre atti Soggetto: libretto di Philipp Eduard Devrient Prima: Berlino, Königliches Opernhaus, 24 maggio 1833 Cast: la regina degli spiriti (S), Hans Heiling (Bar), Anna (S), Gertrude (A), Konrad (T), Stephan (B), Niklas (rec); spiriti, contadini, invitati, giocatori, tiratori Autore: Heinrich Marschner (1795-1861) Il personaggio di Hans Heiling, tra quelli creati da Marschner, rappresenta una delle più notevoli incarnazioni del tipico tema romantico dell’io diviso, condannato a non trovare la propria unità. -

Rosemary Ellen Guiley

vamps_fm[fof]_final pass 2/2/09 10:06 AM Page i The Encyclopedia of VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, and OTHER MONSTERS vamps_fm[fof]_final pass 2/2/09 10:06 AM Page ii The Encyclopedia of VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, and OTHER MONSTERS Rosemary Ellen Guiley FOREWORD BY Jeanne Keyes Youngson, President and Founder of the Vampire Empire The Encyclopedia of Vampires, Werewolves, and Other Monsters Copyright © 2005 by Visionary Living, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guiley, Rosemary. The encyclopedia of vampires, werewolves, and other monsters / Rosemary Ellen Guiley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4684-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4381-3001-9 (e-book) 1. Vampires—Encyclopedias. 2. Werewolves—Encyclopedias. 3. Monsters—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BF1556.G86 2004 133.4’23—dc22 2003026592 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Der Vampyr De Heinrich Marschner

DESCUBRIMIENTOS Der Vampyr de Heinrich Marschner por Carlos Fuentes y Espinosa ay momentos extraordinarios Polidori creó ahí su obra más famosa y trascendente, pues introdujo en un breve cuento de en la historia de la Humanidad horror gótico, por vez primera, una concreción significativa de las creencias folclóricas sobre que, con todo gusto, el vampirismo, dibujando así el prototipo de la concepción que se ha tenido del monstruo uno querría contemplar, desde entonces, al que glorias de la narrativa fantástica como E.T.A. Hoffmann, Edgar Allan dada la importancia de la Poe, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, Jules Verne y el ineludible Abraham Stoker aprovecharían y Hproducción que en ellos se generara. ampliarían magistralmente. Sin duda, un momento especial para la literatura fantástica fue aquella reunión En su relato, Polidori presenta al vampiro, Lord Ruthven, como un antihéroe integrado, a de espléndidos escritores en Ginebra, su manera, a la sociedad, y no es difícil identificar la descripción de Lord Byron en él (sin Suiza, a mediados de junio de 1816 (el mencionar que con ese nombre ya una escritora amante de Byron, Caroline Lamb, nombraba “año sin verano”), cuando en la residencia como Lord Ruthven un personaje con las características del escritor). Precisamente por del célebre George Gordon, Lord Byron, eso, por la publicación anónima original, por la notoria emulación de las obras de Byron y a orillas del lago Lemán, departieron el su fama, las primeras ediciones del cuento se atribuyeron a él, aunque con el tiempo y una baronet Percy Bysshe Shelley, notable incómoda cantidad de disputas, terminara por dársele el crédito al verdadero escritor, que poeta y escritor, su futura esposa Mary fuera tío del poeta y pintor inglés Dante Gabriel Rossetti. -

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century Carlen Lavigne McGill University, Montréal Department of Art History and Communication Studies February 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies © Carlen Lavigne 2008 2 Abstract This study analyzes works of cyberpunk literature written between 1981 and 2005, and positions women’s cyberpunk as part of a larger cultural discussion of feminist issues. It traces the origins of the genre, reviews critical reactions, and subsequently outlines the ways in which women’s cyberpunk altered genre conventions in order to advance specifically feminist points of view. Novels are examined within their historical contexts; their content is compared to broader trends and controversies within contemporary feminism, and their themes are revealed to be visible reflections of feminist discourse at the end of the twentieth century. The study will ultimately make a case for the treatment of feminist cyberpunk as a unique vehicle for the examination of contemporary women’s issues, and for the analysis of feminist science fiction as a complex source of political ideas. Cette étude fait l’analyse d’ouvrages de littérature cyberpunk écrits entre 1981 et 2005, et situe la littérature féminine cyberpunk dans le contexte d’une discussion culturelle plus vaste des questions féministes. Elle établit les origines du genre, analyse les réactions culturelles et, par la suite, donne un aperçu des différentes manières dont la littérature féminine cyberpunk a transformé les usages du genre afin de promouvoir en particulier le point de vue féministe. -

Vampirism, Vampire Cults and the Teenager of Today Megan White University of Kentucky

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Pediatrics Faculty Publications Pediatrics 6-2010 Vampirism, Vampire Cults and the Teenager of Today Megan White University of Kentucky Hatim A. Omar University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/pediatrics_facpub Part of the Pediatrics Commons Repository Citation White, Megan and Omar, Hatim A., "Vampirism, Vampire Cults and the Teenager of Today" (2010). Pediatrics Faculty Publications. 75. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/pediatrics_facpub/75 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Pediatrics at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pediatrics Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vampirism, Vampire Cults and the Teenager of Today Notes/Citation Information Published in International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, v. 22, no. 2, p. 189-195. © Freund Publishing House Ltd. The opc yright holder has granted permission for posting the article here. Digital Object Identifier (DOI) http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/IJAMH.2010.22.2.177 This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/pediatrics_facpub/75 ©Freund Publishing House Ltd. Int J Adolesc Med Health 20 I 0;22(2): 189-195 Vampirism, vampire cults and the teenager of today Megan White, MD and Hatim Omar, MD Division of Adolescent Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, United States ofAmerica Abstract: The aim of this paper is to summarize the limited literature on clinical vampirism, vampire cults and the involvement of adolescents in vampire-like behavior.