Switzerland Health Care Systems in Transition I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

80.823 Frauenfeld - Stammheim - Diessenhofen Stand: 12

FAHRPLANJAHR 2021 80.823 Frauenfeld - Stammheim - Diessenhofen Stand: 12. Oktober 2020 Montag–Freitag ohne allg. Feiertage ohne 1.5. 82301 82303 82305 82307 82309 82311 82313 82315 82317 82319 82321 Frauenfeld, Bahnhof 05 16 05 46 06 16 07 16 07 37 08 16 09 16 10 16 11 16 Frauenfeld, 05 18 05 48 06 18 07 18 07 39 08 18 09 18 10 18 11 18 Schaffhauserplatz Frauenfeld, Sportplatz 05 19 05 49 06 19 07 19 07 40 08 19 09 19 10 19 11 19 Weiningen TG, Dorfplatz 05 25 05 55 06 25 07 25 07 46 08 25 09 25 10 25 11 25 Hüttwilen, Oberdorf 07 53 Hüttwilen, Zentrum 05 29 05 59 06 29 07 29 08 29 09 29 10 29 11 29 Nussbaumen TG, 05 32 06 02 06 32 07 32 08 32 09 32 10 32 11 32 Schulhaus Oberstammheim, Post 05 36 06 06 06 36 07 36 08 36 09 36 10 36 11 36 Stammheim, Bahnhof 05 38 06 08 06 16 06 38 07 16 07 38 08 38 09 38 10 38 11 38 Schlattingen, 05 42 06 12 06 20 06 42 07 20 07 42 08 42 09 42 10 42 11 42 Hauptstrasse Basadingen, Unterdorf 05 44 06 14 06 22 06 44 07 22 07 44 08 44 09 44 10 44 11 44 Diessenhofen, Bahnhof 05 51 06 21 06 30 06 51 07 30 07 51 08 51 09 51 10 51 11 51 82323 82325 82327 82329 82331 82333 82335 82337 82339 82341 82343 Frauenfeld, Bahnhof 12 16 13 16 14 16 15 16 16 16 16 51 17 16 17 51 Frauenfeld, 12 18 13 18 14 18 15 18 16 18 16 53 17 18 17 53 Schaffhauserplatz Frauenfeld, Sportplatz 12 19 13 19 14 19 15 19 16 19 16 54 17 19 17 54 Weiningen TG, Dorfplatz 12 25 13 25 14 25 15 25 16 25 17 00 17 25 18 00 Hüttwilen, Oberdorf 17 07 18 07 Hüttwilen, Zentrum 12 29 13 29 14 29 15 29 16 29 17 29 Nussbaumen TG, 12 32 13 32 14 32 15 32 16 -

No. 2138 BELGIUM, FRANCE, ITALY, LUXEMBOURG, NETHERLANDS

No. 2138 BELGIUM, FRANCE, ITALY, LUXEMBOURG, NETHERLANDS, NORWAY, SWEDEN and SWITZERLAND International Convention to facilitate the crossing of fron tiers for passengers and baggage carried by rail (with annex). Signed at Geneva, on 10 January 1952 Official texts: English and French. Registered ex officio on 1 April 1953. BELGIQUE, FRANCE, ITALIE, LUXEMBOURG, NORVÈGE, PAYS-BAS, SUÈDE et SUISSE Convention internationale pour faciliter le franchissement des frontières aux voyageurs et aux bagages transportés par voie ferrée (avec annexe). Signée à Genève, le 10 janvier 1952 Textes officiels anglais et français. Enregistrée d'office le l* r avril 1953. 4 United Nations — Treaty Series 1953 No. 2138. INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION1 TO FACILI TATE THE CROSSING OF FRONTIERS FOR PASSEN GERS AND BAGGAGE CARRIED BY RAIL. SIGNED AT GENEVA, ON 10 JANUARY 1952 The undersigned, duly authorized, Meeting at Geneva, under the auspices of the Economic Commission for Europe, For the purpose of facilitating the crossing of frontiers for passengers carried by rail, Have agreed as follows : CHAPTER I ESTABLISHMENT AND OPERATION OF FRONTIER STATIONS WHERE EXAMINATIONS ARE CARRIED OUT BY THE TWO ADJOINING COUNTRIES Article 1 1. On every railway line carrying a considerable volume of international traffic, which crosses the frontier between two adjoining countries, the competent authorities of those countries shall, wherever examination cannot be satisfactorily carried out while the trains are in motion, jointly examine the possibility of designating by agreement a station close to the frontier, at which shall be carried out the examinations required under the legislation of the two countries in respect of the entry and exit of passengers and their baggage. -

Three Approaches to Fixing the World Trade Organization's Appellate

Institute of International Economic Law Georgetown University Law Center 600 New Jersey Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20001 [email protected]; http://iielaw.org/ THREE APPROACHES TO FIXING THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION’S APPELLATE BODY: THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY? By Jennifer Hillman, Professor, Georgetown University Law Center* The basic rule book for international trade consists of the legal texts agreed to by the countries that set up the World Trade Organization (WTO) along with specific provisions of its predecessor, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). At the heart of that rules-based system has been a dispute settlement process by which countries resolve any disputes they have about whether another country has violated those rules or otherwise negated the benefit of the bargain between countries. Now the very existence of that dispute settlement system is threatened by a decision of the Trump Administration to block the appointment of any new members to the dispute settlement system’s highest court, its Appellate Body. Under the WTO rules, the Appellate Body is supposed to be comprised of seven people who serve a four-year term and who may be reappointed once to a second four-year term.1 However, the Appellate Body is now * Jennifer Hillman is a Professor from Practice at Georgetown University in Washington, DC and a Distinguished Senior Fellow of its Institute of International Economic Law. She is a former member of the WTO Appellate Body and a former Ambassador and General Counsel in the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). She would like to thank her research assistant, Archana Subramanian, along with Yuxuan Chen and Ricardo Melendez- Ortiz from the International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD) for their invaluable assistance with this article. -

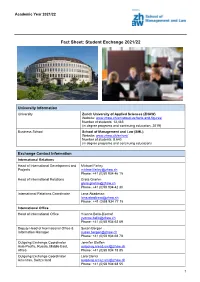

ZHAW SML Fact Sheet 2021-2022.Pdf

Academic Year 2021/22 Fact Sheet: Student Exchange 2021/22 University Information University Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW) Website: www.zhaw.ch/en/about-us/facts-and-figures/ Number of students: 13,485 (in degree programs and continuing education, 2019) Business School School of Management and Law (SML) Website: www.zhaw.ch/en/sml/ Number of students: 8,640 (in degree programs and continuing education) Exchange Contact Information International Relations Head of International Development and Michael Farley Projects [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 46 15 Head of International Relations Greta Gnehm [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 42 30 International Relations Coordinator Lena Abadesso [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 77 15 International Office Head of International Office Yvonne Bello-Bischof [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 62 69 Deputy Head of International Office & Susan Bergen Information Manager [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 68 78 Outgoing Exchange Coordinator Jennifer Steffen Asia-Pacific, Russia, Middle East, [email protected] Africa Phone: +41 (0)58 934 78 85 Outgoing Exchange Coordinator Lara Clerici Americas, Switzerland [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 68 55 1 Academic Year 2021/22 Outgoing Exchange Coordinator Miguel Corredera Europe [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 41 02 Incoming Exchange Coordinator Alice Ragueneau Overseas [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 62 51 Incoming Exchange Coordinator Sandra Aerne Europe -

Upper Rhine Valley: a Migration Crossroads of Middle European Oaks

Upper Rhine Valley: A migration crossroads of middle European oaks Authors: Charalambos Neophytou & Hans-Gerhard Michiels Authors’ affiliation: Forest Research Institute (FVA) Baden-Württemberg Wonnhaldestr. 4 79100 Freiburg Germany Author for correspondence: Charalambos Neophytou Postal address: Forest Research Institute (FVA) Baden-Württemberg Wonnhaldestr. 4 79100 Freiburg Germany Telephone number: +49 761 4018184 Fax number: +49 761 4018333 E-mail address: [email protected] Short running head: Upper Rhine oak phylogeography 1 ABSTRACT 2 The indigenous oak species (Quercus spp.) of the Upper Rhine Valley have migrated to their 3 current distribution range in the area after the transition to the Holocene interglacial. Since 4 post-glacial recolonization, they have been subjected to ecological changes and human 5 impact. By using chloroplast microsatellite markers (cpSSRs), we provide detailed 6 phylogeographic information and we address the contribution of natural and human-related 7 factors to the current pattern of chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) variation. 626 individual trees 8 from 86 oak stands including all three indigenous oak species of the region were sampled. In 9 order to verify the refugial origin, reference samples from refugial areas and DNA samples 10 from previous studies with known cpDNA haplotypes (chlorotypes) were used. Chlorotypes 11 belonging to three different maternal lineages, corresponding to the three main glacial 12 refugia, were found in the area. These were spatially structured and highly introgressed 13 among species, reflecting past hybridization which involved all three indigenous oak species. 14 Site condition heterogeneity was found among groups of populations which differed in 15 terms of cpDNA variation. This suggests that different biogeographic subregions within the 16 Upper Rhine Valley were colonized during separate post-glacial migration waves. -

Insights Into the Thermal History of North-Eastern Switzerland—Apatite

geosciences Article Insights into the Thermal History of North-Eastern Switzerland—Apatite Fission Track Dating of Deep Drill Core Samples from the Swiss Jura Mountains and the Swiss Molasse Basin Diego Villagómez Díaz 1,2,* , Silvia Omodeo-Salé 1 , Alexey Ulyanov 3 and Andrea Moscariello 1 1 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Geneva, 13 rue des Maraîchers, 1205 Geneva, Switzerland; [email protected] (S.O.-S.); [email protected] (A.M.) 2 Tectonic Analysis Ltd., Chestnut House, Duncton, West Sussex GU28 0LH, UK 3 Institut des sciences de la Terre, University of Lausanne, Géopolis, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This work presents new apatite fission track LA–ICP–MS (Laser Ablation Inductively Cou- pled Plasma Mass Spectrometry) data from Mid–Late Paleozoic rocks, which form the substratum of the Swiss Jura mountains (the Tabular Jura and the Jura fold-and-thrust belt) and the northern margin of the Swiss Molasse Basin. Samples were collected from cores of deep boreholes drilled in North Switzerland in the 1980s, which reached the crystalline basement. Our thermochronological data show that the region experienced a multi-cycle history of heating and cooling that we ascribe to burial and exhumation, respectively. Sedimentation in the Swiss Jura Mountains occurred continuously from Early Triassic to Early Cretaceous, leading to the deposition of maximum 2 km of sediments. Subsequently, less than 1 km of Lower Cretaceous and Upper Jurassic sediments were slowly eroded during the Late Cretaceous, plausibly as a consequence of the northward migration of the forebulge Citation: Villagómez Díaz, D.; Omodeo-Salé, S.; Ulyanov, A.; of the neo-forming North Alpine Foreland Basin. -

The False Basel Earthquake of May 12, 1021

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library J Seismol (2008) 12:125–129 DOI 10.1007/s10950-007-9071-1 ORIGINAL ARTICLE The false Basel earthquake of May 12, 1021 Gabriela Schwarz-Zanetti & Virgilio Masciadri & Donat Fäh & Philipp Kästli Received: 2 May 2007 /Accepted: 31 October 2007 / Published online: 7 December 2007 # Springer Science + Business Media B.V. 2007 Abstract The Basel (CH) area is a place with an epicenter located a few kilometers to the south of increased seismic hazard. Consequently, it is essential to Basel (Fäh et al. 2007). Nowadays, an event of this scrutinize a famous statement by Stumpf (Gemeiner size would cause estimated damage of up to 50 billion loblicher Eydgnoschafft Stetten, Landen und Völckeren euros for Switzerland only (Schmid and Schraft Chronikwirdiger thaaten beschreybung. Durch Johann 2000). In subsequent centuries, major seismic events Stumpffen beschriben, 1548) that allegedly a large occurred in the years 1357, 1428, 1572, 1610, 1650, earthquake took place in Basel in 1021. This can be and 1682, all reaching an intensity of VII. Since then, disproved unambiguously by applying historical and only minor earthquakes occurred (ECOS 2002 and philosophical methods. Fäh et al. 2003). Earthquakes in prehistoric times might have caused several earthquake-induced struc- Keywords Macroseismic . Middle Ages . Basel . tures, revealed by paleo-seismological investigations False earthquake . Historical seismology. of lake deposits in the Basel area (Becker et al. 2002). Critical assessment of sources Based on observations of two lakes, five events were detected. Three of them are most probably related to earthquakes that occurred between 180–1160 BC, 1 Introduction 8260–9040 BC, and 10720–11200 BC, respectively. -

Response of Drainage Systems to Neogene Evolution of the Jura Fold-Thrust Belt and Upper Rhine Graben

1661-8726/09/010057-19 Swiss J. Geosci. 102 (2009) 57–75 DOI 10.1007/s00015-009-1306-4 Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, 2009 Response of drainage systems to Neogene evolution of the Jura fold-thrust belt and Upper Rhine Graben PETER A. ZIEGLER* & MARIELLE FRAEFEL Key words: Neotectonics, Northern Switzerland, Upper Rhine Graben, Jura Mountains ABSTRACT The eastern Jura Mountains consist of the Jura fold-thrust belt and the late Pliocene to early Quaternary (2.9–1.7 Ma) Aare-Rhine and Doubs stage autochthonous Tabular Jura and Vesoul-Montbéliard Plateau. They are and 5) Quaternary (1.7–0 Ma) Alpine-Rhine and Doubs stage. drained by the river Rhine, which flows into the North Sea, and the river Development of the thin-skinned Jura fold-thrust belt controlled the first Doubs, which flows into the Mediterranean. The internal drainage systems three stages of this drainage system evolution, whilst the last two stages were of the Jura fold-thrust belt consist of rivers flowing in synclinal valleys that essentially governed by the subsidence of the Upper Rhine Graben, which are linked by river segments cutting orthogonally through anticlines. The lat- resumed during the late Pliocene. Late Pliocene and Quaternary deep incision ter appear to employ parts of the antecedent Jura Nagelfluh drainage system of the Aare-Rhine/Alpine-Rhine and its tributaries in the Jura Mountains and that had developed in response to Late Burdigalian uplift of the Vosges- Black Forest is mainly attributed to lowering of the erosional base level in the Back Forest Arch, prior to Late Miocene-Pliocene deformation of the Jura continuously subsiding Upper Rhine Graben. -

Switzerland 4Th Periodical Report

Strasbourg, 15 December 2009 MIN-LANG/PR (2010) 1 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES Fourth Periodical Report presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in accordance with Article 15 of the Charter SWITZERLAND Periodical report relating to the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages Fourth report by Switzerland 4 December 2009 SUMMARY OF THE REPORT Switzerland ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (Charter) in 1997. The Charter came into force on 1 April 1998. Article 15 of the Charter requires states to present a report to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe on the policy and measures adopted by them to implement its provisions. Switzerland‘s first report was submitted to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in September 1999. Since then, Switzerland has submitted reports at three-yearly intervals (December 2002 and May 2006) on developments in the implementation of the Charter, with explanations relating to changes in the language situation in the country, new legal instruments and implementation of the recommendations of the Committee of Ministers and the Council of Europe committee of experts. This document is the fourth periodical report by Switzerland. The report is divided into a preliminary section and three main parts. The preliminary section presents the historical, economic, legal, political and demographic context as it affects the language situation in Switzerland. The main changes since the third report include the enactment of the federal law on national languages and understanding between linguistic communities (Languages Law) (FF 2007 6557) and the new model for teaching the national languages at school (—HarmoS“ intercantonal agreement). -

Switzerland1

YEARBOOK OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW - VOLUME 14, 2011 CORRESPONDENTS’ REPORTS SWITZERLAND1 Contents Multilateral Initiatives — Foreign Policy Priorities .................................................................. 1 Multilateral Initiatives — Human Security ................................................................................ 1 Multilateral Initiatives — Disarmament and Non-Proliferation ................................................ 2 Multilateral Initiatives — International Humanitarian Law ...................................................... 4 Multilateral Initiatives — Peace Support Operations ................................................................ 5 Multilateral Initiatives — International Criminal Law .............................................................. 6 Legislation — Implementation of the Rome Statute ................................................................. 6 Cases — International Crimes Trials (War Crimes, Crimes against Humanity, Genocide) .... 12 Cases — Extradition of Alleged War Criminal ....................................................................... 13 Multilateral Initiatives — Foreign Policy Priorities Swiss Federal Council, Foreign Policy Report (2011) <http://www.eda.admin.ch/eda/en/home/doc/publi/ppol.html> Pursuant to the 2011 Foreign Policy Report, one of Switzerland’s objectives at institutional level in 2011 was the improvement of the working methods of the UN Security Council (SC). As a member of the UN ‘Small 5’ group, on 28 March 2012, the Swiss -

BLN 1411 Untersee – Hochrhein – Entwurf

Bundesinventar der Landschaften und Naturdenkmäler von nationaler Bedeutung BLN BLN 1411 Untersee – Hochrhein – Entwurf Kanton Gemeinden Fläche Zürich Berg am Irchel, Bülach, Dachsen, Eglisau, Feuerthalen, Flaach, Flurlingen, 12 578 ha Freienstein-Teufen, Glattfelden, Hüntwangen, Laufen-Uhwiesen, Marthalen, Rheinau, Rorbas, Unterstammheim Schaffhausen Buchberg, Dörflingen, Hemishofen, Neuhausen am Rheinfall, Ramsen, Rüdlingen, Schaffhausen, Stein am Rhein Thurgau Basadingen-Schlattingen, Berlingen, Diessenhofen, Ermatingen, Eschenz, Gottlieben, Herdern, Homburg, Mammern, Raperswilen, Salenstein, Schlatt, Steckborn, Tägerwilen, Wagenhausen, Wäldi 1 BLN 1411 Untersee – Hochrhein – Entwurf Rhein zwischen Rüdlingen und Tössegg BLN 1411 Untersee – Hochrhein Stein am Rhein mit Kloster St. Georg, Schloss Naturschutzgebiet Scharen mit Sibirischer Schwertlilie Hohenklingen Töss vor der Mündung in den Rhein, Tössegg Ehemalige Stadtmauer, Bergkirche und Klosterinsel Rheinau 2 BLN 1411 Untersee – Hochrhein – Entwurf 1 Begründung der nationalen Bedeutung 1.1 Naturnahe See- und Flusslandschaft mit einer Vielzahl bedeutender landschafts- und kultur- geschichtlicher Zeugen. 1.2 Frei fliessender Seerhein sowie drei noch frei fliessende Abschnitte. 1.3 Längere Schluchtabschnitte mit bewaldeten Steilstufen. 1.4 Grosser Reichtum an vielfältigen Lebensräumen mit Bezug zur See- und Flusslandschaft. 1.5 Bedeutendes Überwinterungs- und Rastgebiet für Wasser- und Zugvögel. 1.6 Vorkommen seltener Pflanzen- und Tierarten. 1.7 Bedeutendes Gewässer für charakteristische -

Taxation and Investment in Switzerland 2015 Reach, Relevance and Reliability

Taxation and Investment in Switzerland 2015 Reach, relevance and reliability A publication of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited Contents 1.0 Investment climate 1.1 Business environment 1.2 Currency 1.3 Banking and financing 1.4 Foreign investment 1.5 Tax incentives 1.6 Exchange controls 2.0 Setting up a business 2.1 Principal forms of business entity 2.2 Regulation of business 2.3 Accounting, filing and auditing requirements 3.0 Business taxation 3.1 Overview 3.2 Residence 3.3 Taxable income and rates 3.4 Capital gains taxation 3.5 Double taxation relief 3.6 Anti-avoidance rules 3.7 Administration 3.8 Other taxes on business 4.0 Withholding taxes 4.1 Dividends 4.2 Interest 4.3 Royalties 4.4 Branch remittance tax 4.5 Wage tax/social security contributions 4.6 Other 5.0 Indirect taxes 5.1 Value added tax 5.2 Capital tax 5.3 Real estate tax 5.4 Transfer tax 5.5 Stamp duty 5.6 Customs and excise duties 5.7 Environmental taxes 5.8 Other taxes 6.0 Taxes on individuals 6.1 Residence 6.2 Taxable income and rates 6.3 Inheritance and gift tax 6.4 Net wealth tax 6.5 Real property tax 6.6 Social security contributions 6.7 Other taxes 6.8 Compliance 7.0 Labor environment 7.1 Employee rights and remuneration 7.2 Wages and benefits 7.3 Termination of employment 7.4 Labor-management relations 7.5 Employment of foreigners 8.0 Deloitte International Tax Source 9.0 Contact us 1.0 Investment climate 1.1 Business environment Switzerland is comprised of the federal state and 26 cantons, which are member states of the federal state.