Astroex.Org/ Lectures Conseillées

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESA/ESO Astronomy Exercise Series A

had a look into the control room, where the different purposes of the computers and monitors were illustrated. After dinner we went again up on the mountain and we saw the opening of the telescopes. The winners were real- ly excited seeing the “big brother” of the NTT moving. After sunset we stayed for a long time in the control room. We got explanations of the instruments mount- ed on each telescope as well as of the objects imaged that night. The Tele- scope Operators, the Staff Astronom- ers and the Visiting Astronomers kindly explained us their work. Of course, on both observatories we had the possibility to ask questions, which was very important for the win- ners, not just hearing astronomers talk- ing, but speaking directly to them. Although the long trip was very ex- VLT: The winners and Gerd Hudepohl in front of UT1. hausting, we forgot it completely seeing the observatories. All are thankful to The next destination was the Paranal got a visit to UT1, ANTU, by day. The ESO for providing this nice prize and Observatory. Humberto Varas was our active optics system and the mounted the opportunity to see the sites, where guide and showed us the site. First we instruments were explained. We also real frontline astronomy is done. In the Footsteps of Scientists – ESA/ESO Astronomy Exercise Series A. BACHER1 and L. LINDBERG CHRISTENSEN2 1ESO and Institut für Astrophysik, Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck; 2ST-ECF The first instalments of the “ESA/ ESO Astronomy Exercise Series” has been published, on the web and in print (see also ESO PR 29/01). -

Messier Objects

Messier Objects From the Stocker Astroscience Center at Florida International University Miami Florida The Messier Project Main contributors: • Daniel Puentes • Steven Revesz • Bobby Martinez Charles Messier • Gabriel Salazar • Riya Gandhi • Dr. James Webb – Director, Stocker Astroscience center • All images reduced and combined using MIRA image processing software. (Mirametrics) What are Messier Objects? • Messier objects are a list of astronomical sources compiled by Charles Messier, an 18th and early 19th century astronomer. He created a list of distracting objects to avoid while comet hunting. This list now contains over 110 objects, many of which are the most famous astronomical bodies known. The list contains planetary nebula, star clusters, and other galaxies. - Bobby Martinez The Telescope The telescope used to take these images is an Astronomical Consultants and Equipment (ACE) 24- inch (0.61-meter) Ritchey-Chretien reflecting telescope. It has a focal ratio of F6.2 and is supported on a structure independent of the building that houses it. It is equipped with a Finger Lakes 1kx1k CCD camera cooled to -30o C at the Cassegrain focus. It is equipped with dual filter wheels, the first containing UBVRI scientific filters and the second RGBL color filters. Messier 1 Found 6,500 light years away in the constellation of Taurus, the Crab Nebula (known as M1) is a supernova remnant. The original supernova that formed the crab nebula was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Arab astronomers in 1054 AD as an incredibly bright “Guest star” which was visible for over twenty-two months. The supernova that produced the Crab Nebula is thought to have been an evolved star roughly ten times more massive than the Sun. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Desert Skies

Desert Skies Tucson Amateur Astronomy Association Volume LII, Number 7 July, 2006 Dark globule in the emission nebula IC 1396 contains never-before-seen young stars ♦ Learn about the Spitzer Infrared ♦ Websites: Gimme Shelter Part 4 Telescope ♦ Object of the Month ♦ Star parties and Meetings ♦ Constellation of the month Desert Skies: July, 2006 2 Volume LII, Number 7 Cover Photo: The Spitzer image of this globule is in spectacular contrast to the view seen in visible light. Spitzer's infra- red detectors unveiled the brilliant hidden interior of this opaque cloud of gas and dust for the first time, exposing never- before-seen young stars. Image: http://sscws1.ipac.caltech.edu/Imagegallery/image.php?image_name=ssc2003-06b TAAA Web Page: http://www.tucsonastronomy.org TAAA Phone Number: (520) 792-6414 Office/Position Name Phone E-mail Address President Bill Lofquist 297-6653 [email protected] Vice President Ken Shaver 762-5094 [email protected] Secretary Steve Marten 307-5237 [email protected] Treasurer Terri Lappin 977-1290 [email protected] Member-at-Large George Barber 822-2392 [email protected] Member-at-Large JD Metzger 760-8248 [email protected] Member-at-Large Teresa Plymate 883-9113 [email protected] Chief Observer Wayne Johnson 586-2244 [email protected] AL Correspondent (ALCor) Nick de Mesa 797-6614 [email protected] Astro-Imaging SIG Steve Peterson 762-8211 [email protected] Computers in Astronomy SIG Roger Tanner -

The Messier Catalog

The Messier Catalog Messier 1 Messier 2 Messier 3 Messier 4 Messier 5 Crab Nebula globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 6 Messier 7 Messier 8 Messier 9 Messier 10 open cluster open cluster Lagoon Nebula globular cluster globular cluster Butterfly Cluster Ptolemy's Cluster Messier 11 Messier 12 Messier 13 Messier 14 Messier 15 Wild Duck Cluster globular cluster Hercules glob luster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 16 Messier 17 Messier 18 Messier 19 Messier 20 Eagle Nebula The Omega, Swan, open cluster globular cluster Trifid Nebula or Horseshoe Nebula Messier 21 Messier 22 Messier 23 Messier 24 Messier 25 open cluster globular cluster open cluster Milky Way Patch open cluster Messier 26 Messier 27 Messier 28 Messier 29 Messier 30 open cluster Dumbbell Nebula globular cluster open cluster globular cluster Messier 31 Messier 32 Messier 33 Messier 34 Messier 35 Andromeda dwarf Andromeda Galaxy Triangulum Galaxy open cluster open cluster elliptical galaxy Messier 36 Messier 37 Messier 38 Messier 39 Messier 40 open cluster open cluster open cluster open cluster double star Winecke 4 Messier 41 Messier 42/43 Messier 44 Messier 45 Messier 46 open cluster Orion Nebula Praesepe Pleiades open cluster Beehive Cluster Suburu Messier 47 Messier 48 Messier 49 Messier 50 Messier 51 open cluster open cluster elliptical galaxy open cluster Whirlpool Galaxy Messier 52 Messier 53 Messier 54 Messier 55 Messier 56 open cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 57 Messier -

January 2002 30

January 2002 30 The Red Spider Nebula, NGC 6537, is a striking ‘butterfly’ or bipolar planetary nebula. This NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope image shows that the gas walls of the two lobed structures are not smooth, but rippled in a complex way. These waves are driven by stellar winds radiating from the hot central star. The image was created from exposures through five different filters: ionised sulphur (red), ionised nitrogen (orange), ionised hydrogen (green), atomic oxygen (light blue) and ionised oxygen (dark blue). ESA & Garrelt Mellema ESA & Garrelt The Netherlands) (Leiden University, Read more at http://hubble.esa.int under “Releases” (heic0109) Page 2 ST-ECF Newsletter 30 HST News and Status Jeremy Walsh reparations are well advanced for the next HST servicing was determined to be a short circuit in the low voltage power mission, SM3B, which will include the installation of the supply. Whilst the UV MAMA performance was unaffected by Pfirst new scientific instrument on HST for five years, the the change, the CCD read noise showed an increase from 4.4 to Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS), and the restoration of the 5.4 electrons. This degradation will only affect those program- performance of the NICMOS infrared instrument by the instal- mes performing spectroscopy on faint extended objects. The lation of a cryocooler. Side 2 electronics were known to have a faulty CCD temp- erature sensor before launch, so more monitoring is now The launch of SM3B is currently planned for late February required to manage the result of the changes in temperature of 2002 and the mission should last 11 days, including a total of the CCD housing. -

ASSA Top 100 Deep Sky Objects

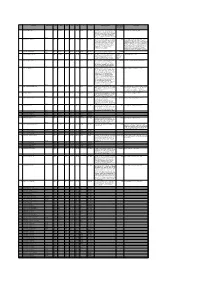

# Object ID Bennett ID Type Size Con RA Dec D Vis Interesting Facts Distance from Discoverer Earth (light- years) 1 NGC 55, LEDA 1014 Glxy 32’x5.6’ Scl 00 15 – 39 11 06,25 Sep–Feb The String of Pearls. A barred galaxy that is 7200000 James Dunlop on August 4, 1826 edge-on to us. It has a bright elongated center with a small round cloud to the east of it. If you look to the side of it while still concentrating on the object you might be able to see additional bright clouds and dark Ben 1 rifts in this galaxy. 2 NGC 104, 47 Tucanae Glcl 31’ Tuc 00 24 – 72 05 05,06 Sep–Feb The cluster appears roughly the size of the 16700 Abbe Lacaille from South Africa, 1751. At the full moon in the sky under ideal conditions. Cape, Abbé wanted to test Newton's theory of It is the second brightest globular cluster in gravitation and verify the shape of the earth in the the sky (after Omega Centauri), and is southern hemisphere. His results suggested the noted for having a very bright and dense Earth was egg-shaped not oval. In 1838, Thomas core. It is also one of the most massive Maclear who was Astronomer Royal at the Cape, globular clusters in the Milky Way, repeated the measurements. He found that de containing millions of stars Lacaille had failed to take into account the gravitational attraction of the nearby mountains. Ben 2 3 NGC 247, LEDA 2758 Glxy 18’ x 5’ Cet 00 47 – 20 46 06,25 Sep–Feb Very dusty galaxy therefore not bright, 11000000 ? Ben 3 magnitude 9.2, challenging to find. -

The Age of Aquarius Is an Astrological Term Denoting Either the Current Or Upcoming Astrological Age, Depending on the Method of Calculation

The Age of Aquarius is an astrological term denoting either the current or upcoming astrological age, depending on the method of calculation. Astrologers maintain that an astrological age is a product of the earth's slow precessional rotation and lasts for 2,150 years, on average. In popular culture in the United States, the Age of Aquarius refers to the advent of the New Age movement in the 1960s and 1970s. There are various methods of calculating the length of an astrological age. In sun- sign astrology, the first sign is Aries, followed by Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius, Capricorn, Aquarius, and Pisces, whereupon the cycle returns to Aries and through the zodiacal signs again. Astrological ages, however, proceed in the opposite direction ("retrograde" in astronomy). Therefore, the Age of Aquarius follows the Age of Pisces. Mythology of the constellation Aquarius This is the eleventh zodiacal sign and one which has always been connected with water. To the Babylonians it represented an overflowing urn, and they associated this with the heavy rains which fell in their eleventh month, whilst the Egyptians saw the constellation as Hapi, the god of the Nile. Greek legend, however, tells of Ganymede, an exceptionally handsome, young prince of Troy. He was spotted by Zeus, who immediately decided that he would make a perfect cup-bearer. The story then differs - one version telling how Zeus sent his pet eagle, Aquila, to carry Ganymede to Olympus, another that it was Zeus, himself, disguised as an eagle, who swept up the youth and carried him to the home of the gods. -

Charles Messier (1730-1817) Was an Observational Astronomer Working

Charles Messier (1730-1817) was an observational Catalogue (NGC) which was being compiled at the same astronomer working from Paris in the eighteenth century. time as Messier's observations but using much larger tele He discovered between 15 and 21 comets and observed scopes, probably explains its modern popularity. It is a many more. During his observations he encountered neb challenging but achievable task for most amateur astron ulous objects that were not comets. Some of these objects omers to observe all the Messier objects. At «star parties" were his own discoveries, while others had been known and within astronomy clubs, going for the maximum before. In 1774 he published a list of 45 of these nebulous number of Messier objects observed is a popular competi objects. His purpose in publishing the list was so that tion. Indeed at some times of the year it is just about poss other comet-hunters should not confuse the nebulae with ible to observe most of them in a single night. comets. Over the following decades he published supple Messier observed from Paris and therefore the most ments which increased the number of objects in his cata southerly object in his list is M7 in Scorpius with a decli logue to 103 though objects M101 and M102 were in fact nation of -35°. He also missed several objects from his list the same. Later other astronomers added a replacement such as h and X Per and the Hyades which most observers for M102 and objects 104 to 110. It is now thought proba would feel should have been included. -

Helen B. Sawyer a Catalogue of 1116 Variable Stars in Globular Star

PUBLICATIONS OF THE DAVID DUNLAP OBSERVATORY UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Volume I Number 4 A CATALOGUE OF 1116 VARIABLE STARS IN GLOBULAR STAR CLUSTERS BY HELEN B. SAWYER 1939 THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS rokoN ni, ( .\\.\h\ A CATALOGUE OF 1116 VARIABLE STARS IN GLOBULAR STAR CLUSTERS by Helen B. Sawyer A. Introduction. It is now fifty years since the discovery of the first variable star was announced in a globular cluster. The Nova which appeared in the cluster Messier 80 in 1860 can hardly be said to be the beginning of variable star astronomy in clusters, as it is still in a class by itself. In 1902 Bailey gave a summary of the variables in all the clusters which he himself had investigated, and published co-ordinates for the variables. Except for this compilation however, no catalogue of the variable stars in globular clusters has ever been published. In 1930 Shapley published in Star Clusters a summary of the variables known in globular clusters. This summary was brought up to date in 1933 in the Ilandbuch der Astrophysik. Considerable knowledge has been added in the interim, with many new variables discovered, and periods determined. In June, 1938, the writer sent a paper to the Ottawa meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science summarizing the present state of our knowledge. As a basis for this paper, a catalogue was made giving the magnitudes, positions, and periods of all the individual variables. There was originally no intention of publishing the actual catalogue of variables, but only a summary of the data contained therein. -

Upper Yarra U3A Astronomy Program 2017

Upper Yarra U3A Astronomy Program 2017 Series of 12 Meetings Schedule, February – July Meeting Structure: * Start 13:00 Three 20 minutes Session (broadly based as below), each followed by 10 minutes Question Time and Discussions - Session a: Great Courses Video (followed by Coffee Break) Completing the Video Series called ?The History and Nature of our Universe” by Professor Mark Whittle we start a new Series called “Skywatching, Seeing and Understanding Cosmic Wonders” by Professor Alex Filippenko - Session b: Features of the Night Sky - Session c: Current Phenomena * Finish at 14:30 ! First Meeting Date: Thursday 9 February ! Seventh Meeting Date: Thursday 4 May a Lecture 36 - A comprehensible Universe a Lecture 6 - Sunrise and Sunset Colours b The Messier Objects b Messier 11 (Wild Duck) in Scutum c This Week’s Sky c This Week’s Sky ! Second Meeting Date: Thursday 23 February ! Eighth Meeting Date: Thursday 18 May a Lecture 1 - Day and Night Sky a Lecture 7 - Stars and Constellations b Messier 6 (Butterfly) in Scorpius b Messier 12, Glob Cluster in Ophiuchus c This Week’s Sky c This Week’s Sky ! Third Meeting Date: Thursday 9 March ! Ninth Meeting Date: Thursday 1 June a Lecture 2 - The Blue Sky a Lecture 8 - Planets and their Motions b Messier 7 (Ptolemy) in Scorpius b Messier 13 (The Great) in Hercules c This Week’s Sky c This Week’s Sky ! Fourth Meeting Date: Thursday 23 March ! Tenth Meeting Date: Thursday 15 June a Lecture 3 - The Rainbow Family a Lecture 9 - The Moon and its Phases b Messier 8 (Lagoon Nebula) Sagittarius b Messier -

Messier 1 Messier 2

Messier 1 { HYPERLINK "http://www.seds.org/messier/nebula.html" } M1 (NGC 1952) in { HYPERLINK "http://www.seds.org/messier/map/Tau.html" } Crab Nebula { HYPERLINK "http://www.seds.org/messier/Jpg/m1.jpg" } Right Ascension 05 : 34.5 (h:m) Declination +22 : 01 (deg:m) Distance 6.3 (kly) Visual Brightness 8.4 (mag) Apparent Dimension 6x4 (arc min) Messier 2 { HYPERLINK "http://www.seds.org/messier/cluster.html" } M2 (NGC 7089) , class II, in { HYPERLINK "http://www.seds.org/messier/map/Aqr.html" } { HYPERLINK "http://www.seds.org/messier/Jpg/m2.jpg" } Right Ascension 21 : 33.5 (h:m) Declination -00 : 49 (deg:m) Distance 37.5 (kly) Visual Brightness 6.5 (mag) Apparent Dimension 16.0 (arc min) Messier 3 { HYPERLINK "http://www.seds.org/messier/cluster.html" } M3 (NGC 5272) , class VI, in { HYPERLINK "http://www.seds.org/messier/map/CVn.html" } { HYPERLINK "http://www.seds.org/messier/Jpg/m3.jpg" } Right Ascension 13 : 42.2 (h:m) Declination +28 : 23 (deg:m) Distance 33.9 (kly) Visual Brightness 6.2 (mag) Apparent Dimension 18.0 (arc min) Messier 4 { HYPERLINK "http://www.seds.org/messier/cluster.html" } M4 (NGC 6121) , class IX, in { HYPERLINK "http://www.seds.org/messier/map/Sco.html" } { HYPERLINK "http://www.seds.org/messier/Jpg/m4.jpg" } Right Ascension 16 : 23.6 (h:m) Declination -26 : 32 (deg:m) Distance 7.2 (kly) Visual Brightness 5.6 (mag) Apparent Dimension 36.0 (arc min) Messier 5 { HYPERLINK "http://www.seds.org/messier/cluster.html" } M5 (NGC 5904) , class V, in { HYPERLINK "http://www.seds.org/messier/map/SerCap.html" } { HYPERLINK