BRS Genetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Information to Mammadova-Bach Et Al., “Laminin Α1 Orchestrates VEGFA Functions in the Ecosystem of Colorectal Carcinogenesis”

Supplemental information to Mammadova-Bach et al., “Laminin α1 orchestrates VEGFA functions in the ecosystem of colorectal carcinogenesis” Supplemental material and methods Cloning of the villin-LMα1 vector The plasmid pBS-villin-promoter containing the 3.5 Kb of the murine villin promoter, the first non coding exon, 5.5 kb of the first intron and 15 nucleotides of the second villin exon, was generated by S. Robine (Institut Curie, Paris, France). The EcoRI site in the multi cloning site was destroyed by fill in ligation with T4 polymerase according to the manufacturer`s instructions (New England Biolabs, Ozyme, Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France). Site directed mutagenesis (GeneEditor in vitro Site-Directed Mutagenesis system, Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France) was then used to introduce a BsiWI site before the start codon of the villin coding sequence using the 5’ phosphorylated primer: 5’CCTTCTCCTCTAGGCTCGCGTACGATGACGTCGGACTTGCGG3’. A double strand annealed oligonucleotide, 5’GGCCGGACGCGTGAATTCGTCGACGC3’ and 5’GGCCGCGTCGACGAATTCACGC GTCC3’ containing restriction site for MluI, EcoRI and SalI were inserted in the NotI site (present in the multi cloning site), generating the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. The SV40 polyA region of the pEGFP plasmid (Clontech, Ozyme, Saint Quentin Yvelines, France) was amplified by PCR using primers 5’GGCGCCTCTAGATCATAATCAGCCATA3’ and 5’GGCGCCCTTAAGATACATTGATGAGTT3’ before subcloning into the pGEMTeasy vector (Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France). After EcoRI digestion, the SV40 polyA fragment was purified with the NucleoSpin Extract II kit (Machery-Nagel, Hoerdt, France) and then subcloned into the EcoRI site of the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. Site directed mutagenesis was used to introduce a BsiWI site (5’ phosphorylated AGCGCAGGGAGCGGCGGCCGTACGATGCGCGGCAGCGGCACG3’) before the initiation codon and a MluI site (5’ phosphorylated 1 CCCGGGCCTGAGCCCTAAACGCGTGCCAGCCTCTGCCCTTGG3’) after the stop codon in the full length cDNA coding for the mouse LMα1 in the pCIS vector (kindly provided by P. -

Gelişimsel Çocuk Nörolojisi 2017

Baskı Mart, 2017 Bu yayının telif hakları Düzen Laboratuvarlar Grubu’na aittir. Bu yayının tümü ya da bir bölümü Düzen Laboratuvarlar Grubu’nun yazılı izni olmadan kopya edilemez. Bu yayın Düzen Laboratuvarlar Grubu tarafından tanıtım ve bilgilendirme amacıyla hazırlanmış olup hazırlanma ve basım esnasında metin ya da grafiklerde oluşabilecek her türlü hata ve eksikliklerden Düzen Laboratuvarlar Grubu sorumlu tutulamaz. Kaynak göstermek ve Düzen Laboratuvarlar Grubu’ndan yazılı izin almak suretiyle bu yayında alıntı yapılabilir. Düzen Laboratuvarlar Grubu Tunus Cad. No. 95 Kavaklıdere Çankaya 06680 Ankara www.duzen.com.tr VİZYONUMUZ Hasta haklarına saygılı, bilgilendirmeyi esas alan, testleri en doğru, izlenebilir ve tekrarlanabilir yöntemlerle çalışmak ve en az hatayı esas kabul edip, iç ve dış kalite kontrolleri ile bu kavramın gerçekleştiğini göstermektedir. MİSYONUMUZ Test sonuçları üzerinde laboratuvarmızın sorumluluğu, testin klinik laboratuvarcılık standartları ve iyi laboratuvar uygulamaları sınırları içinde, tüm kontoller yapılarak çalışılması ile sınırlıdır. Test sonuçları klinik bulgular ve diğer tüm yardımcı veriler dikkate alınarak değerlendirilmektedir. AKREDİTASYON Laboratuvarımız 2004 yılında Türk Akreditasyon Kurumu (TÜRKAK) tarafından TS EN IS IEC 17025 kapsamında akredite edilmiş, 2011 yılından itibaren ise ISO15189 kapsamında akreditasyona hak kazanmıştır. Hasta kayıt, numune alma, raporlama, kurumsal hizmetler ve tüm işletim sistemi akreditasyon kapsamındadır. GÜVENİRLİLİK Laboratuvarımız CLSI programlarına üyedir -

Prox1regulates the Subtype-Specific Development of Caudal Ganglionic

The Journal of Neuroscience, September 16, 2015 • 35(37):12869–12889 • 12869 Development/Plasticity/Repair Prox1 Regulates the Subtype-Specific Development of Caudal Ganglionic Eminence-Derived GABAergic Cortical Interneurons X Goichi Miyoshi,1 Allison Young,1 Timothy Petros,1 Theofanis Karayannis,1 Melissa McKenzie Chang,1 Alfonso Lavado,2 Tomohiko Iwano,3 Miho Nakajima,4 Hiroki Taniguchi,5 Z. Josh Huang,5 XNathaniel Heintz,4 Guillermo Oliver,2 Fumio Matsuzaki,3 Robert P. Machold,1 and Gord Fishell1 1Department of Neuroscience and Physiology, NYU Neuroscience Institute, Smilow Research Center, New York University School of Medicine, New York, New York 10016, 2Department of Genetics & Tumor Cell Biology, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tennessee 38105, 3Laboratory for Cell Asymmetry, RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology, Kobe 650-0047, Japan, 4Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, GENSAT Project, The Rockefeller University, New York, New York 10065, and 5Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, New York 11724 Neurogliaform (RELNϩ) and bipolar (VIPϩ) GABAergic interneurons of the mammalian cerebral cortex provide critical inhibition locally within the superficial layers. While these subtypes are known to originate from the embryonic caudal ganglionic eminence (CGE), the specific genetic programs that direct their positioning, maturation, and integration into the cortical network have not been eluci- dated. Here, we report that in mice expression of the transcription factor Prox1 is selectively maintained in postmitotic CGE-derived cortical interneuron precursors and that loss of Prox1 impairs the integration of these cells into superficial layers. Moreover, Prox1 differentially regulates the postnatal maturation of each specific subtype originating from the CGE (RELN, Calb2/VIP, and VIP). -

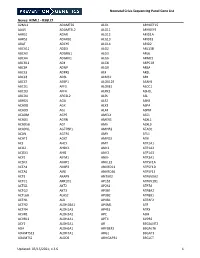

NICU Gene List Generator.Xlsx

Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: A2ML1 - B3GLCT A2ML1 ADAMTS9 ALG1 ARHGEF15 AAAS ADAMTSL2 ALG11 ARHGEF9 AARS1 ADAR ALG12 ARID1A AARS2 ADARB1 ALG13 ARID1B ABAT ADCY6 ALG14 ARID2 ABCA12 ADD3 ALG2 ARL13B ABCA3 ADGRG1 ALG3 ARL6 ABCA4 ADGRV1 ALG6 ARMC9 ABCB11 ADK ALG8 ARPC1B ABCB4 ADNP ALG9 ARSA ABCC6 ADPRS ALK ARSL ABCC8 ADSL ALMS1 ARX ABCC9 AEBP1 ALOX12B ASAH1 ABCD1 AFF3 ALOXE3 ASCC1 ABCD3 AFF4 ALPK3 ASH1L ABCD4 AFG3L2 ALPL ASL ABHD5 AGA ALS2 ASNS ACAD8 AGK ALX3 ASPA ACAD9 AGL ALX4 ASPM ACADM AGPS AMELX ASS1 ACADS AGRN AMER1 ASXL1 ACADSB AGT AMH ASXL3 ACADVL AGTPBP1 AMHR2 ATAD1 ACAN AGTR1 AMN ATL1 ACAT1 AGXT AMPD2 ATM ACE AHCY AMT ATP1A1 ACO2 AHDC1 ANK1 ATP1A2 ACOX1 AHI1 ANK2 ATP1A3 ACP5 AIFM1 ANKH ATP2A1 ACSF3 AIMP1 ANKLE2 ATP5F1A ACTA1 AIMP2 ANKRD11 ATP5F1D ACTA2 AIRE ANKRD26 ATP5F1E ACTB AKAP9 ANTXR2 ATP6V0A2 ACTC1 AKR1D1 AP1S2 ATP6V1B1 ACTG1 AKT2 AP2S1 ATP7A ACTG2 AKT3 AP3B1 ATP8A2 ACTL6B ALAS2 AP3B2 ATP8B1 ACTN1 ALB AP4B1 ATPAF2 ACTN2 ALDH18A1 AP4M1 ATR ACTN4 ALDH1A3 AP4S1 ATRX ACVR1 ALDH3A2 APC AUH ACVRL1 ALDH4A1 APTX AVPR2 ACY1 ALDH5A1 AR B3GALNT2 ADA ALDH6A1 ARFGEF2 B3GALT6 ADAMTS13 ALDH7A1 ARG1 B3GAT3 ADAMTS2 ALDOB ARHGAP31 B3GLCT Updated: 03/15/2021; v.3.6 1 Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: B4GALT1 - COL11A2 B4GALT1 C1QBP CD3G CHKB B4GALT7 C3 CD40LG CHMP1A B4GAT1 CA2 CD59 CHRNA1 B9D1 CA5A CD70 CHRNB1 B9D2 CACNA1A CD96 CHRND BAAT CACNA1C CDAN1 CHRNE BBIP1 CACNA1D CDC42 CHRNG BBS1 CACNA1E CDH1 CHST14 BBS10 CACNA1F CDH2 CHST3 BBS12 CACNA1G CDK10 CHUK BBS2 CACNA2D2 CDK13 CILK1 BBS4 CACNB2 CDK5RAP2 -

Maple Syrup Urine Disease Mutation Spectrum in a Cohort of 40 Consanguineous Patients and Insilico Analysis of Novel Mutations

Metabolic Brain Disease (2019) 34:1145–1156 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-019-00435-y ORIGINAL ARTICLE Maple syrup urine disease mutation spectrum in a cohort of 40 consanguineous patients and insilico analysis of novel mutations Maryam Abiri1 & Hassan Saei1,2 & Maryam Eghbali3 & Razieh Karamzadeh4 & Tina Shirzadeh5,6 & Zohreh Sharifi5,6 & Sirous Zeinali5,7 Received: 28 February 2019 /Accepted: 13 May 2019 /Published online: 22 May 2019 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Maple syrup urine disease is the primary aminoacidopathy affecting branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) metabolism. The disease is mainly caused by the deficiency of an enzyme named branched-chained α-keto acid dehydrogenase (BCKD), which consist of four subunits (E1α,E1β, E2, and E3), and encoded by BCKDHA, BCKDHB, DBT,andDLD gene respectively. BCKD is the main enzyme in the catabolism pathway of BCAAs. Hight rate of autosomal recessive disorders is expected from consanguineous populations like Iran. In this study, we selected two sets of STR markers linked to the four genes, that mutation in which can result in MSUD disease. The patients who had a homozygous haplotype for selected markers of the genes were sequenced. In current survey, we summarized our recent molecular genetic findings to illustrate the mutation spectrum of MSUD in our country. Ten novel mutations including c.484 A > G, c.834_836dup CAC, c.357del T, and c. (343 + 1_344–1) _ (742 + 1_743–1)del in BCKDHB,c.355–356 ins 7 nt ACAAGGA, and c.703del T in BCKDHA, and c.363delCT/c.1238 T > C, c. -

A Novel Whole Gene Deletion of BCKDHB by Alu-Mediated Non-Allelic Recombination in a Chinese Patient with Maple Syrup Urine Disease

fgene-09-00145 April 21, 2018 Time: 11:38 # 1 CASE REPORT published: 24 April 2018 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00145 A Novel Whole Gene Deletion of BCKDHB by Alu-Mediated Non-allelic Recombination in a Chinese Patient With Maple Syrup Urine Disease Gang Liu1†, Dingyuan Ma1†, Ping Hu1, Wen Wang2, Chunyu Luo1, Yan Wang1, Yun Sun1, Jingjing Zhang1, Tao Jiang1* and Zhengfeng Xu1* 1 State Key Laboratory of Reproductive Medicine, Department of Prenatal Diagnosis, The Affiliated Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, Nanjing, China, 2 Reproductive Genetic Center, Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou, China Edited by: Musharraf Jelani, Maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) is an autosomal recessive inherited metabolic King Abdulaziz University, disorder caused by mutations in the BCKDHA, BCKDHB, DBT, and DLD genes. Among Saudi Arabia the wide range of disease-causing mutations in BCKDHB, only one large deletion has Reviewed by: Michael L. Raff, been associated with MSUD. Compound heterozygous mutations in BCKDHB were MultiCare Health System, identified in a Chinese patient with typical MSUD using next-generation sequencing, United States quantitative PCR, and array comparative genomic hybridization. One allele presented Bruna De Felice, Università degli Studi della Campania a missense mutation (c.391G > A), while the other allele had a large deletion; both “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Italy were inherited from the patient’s unaffected parents. The deletion breakpoints were *Correspondence: characterized using long-range PCR and sequencing. A novel 383,556 bp deletion Tao Jiang [email protected] (chr6: g.80811266_81194921del) was determined, which encompassed the entire Zhengfeng Xu BCKDHB gene. -

Genetic Testing Policy Number: PG0041 ADVANTAGE | ELITE | HMO Last Review: 04/11/2021

Genetic Testing Policy Number: PG0041 ADVANTAGE | ELITE | HMO Last Review: 04/11/2021 INDIVIDUAL MARKETPLACE | PROMEDICA MEDICARE PLAN | PPO GUIDELINES This policy does not certify benefits or authorization of benefits, which is designated by each individual policyholder terms, conditions, exclusions and limitations contract. It does not constitute a contract or guarantee regarding coverage or reimbursement/payment. Paramount applies coding edits to all medical claims through coding logic software to evaluate the accuracy and adherence to accepted national standards. This medical policy is solely for guiding medical necessity and explaining correct procedure reporting used to assist in making coverage decisions and administering benefits. SCOPE X Professional X Facility DESCRIPTION A genetic test is the analysis of human DNA, RNA, chromosomes, proteins, or certain metabolites in order to detect alterations related to a heritable or acquired disorder. This can be accomplished by directly examining the DNA or RNA that makes up a gene (direct testing), looking at markers co-inherited with a disease-causing gene (linkage testing), assaying certain metabolites (biochemical testing), or examining the chromosomes (cytogenetic testing). Clinical genetic tests are those in which specimens are examined and results reported to the provider or patient for the purpose of diagnosis, prevention or treatment in the care of individual patients. Genetic testing is performed for a variety of intended uses: Diagnostic testing (to diagnose disease) Predictive -

Supplementary Table 2

Supplementary Table 2. Differentially Expressed Genes following Sham treatment relative to Untreated Controls Fold Change Accession Name Symbol 3 h 12 h NM_013121 CD28 antigen Cd28 12.82 BG665360 FMS-like tyrosine kinase 1 Flt1 9.63 NM_012701 Adrenergic receptor, beta 1 Adrb1 8.24 0.46 U20796 Nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 2 Nr1d2 7.22 NM_017116 Calpain 2 Capn2 6.41 BE097282 Guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha 12 Gna12 6.21 NM_053328 Basic helix-loop-helix domain containing, class B2 Bhlhb2 5.79 NM_053831 Guanylate cyclase 2f Gucy2f 5.71 AW251703 Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 12a Tnfrsf12a 5.57 NM_021691 Twist homolog 2 (Drosophila) Twist2 5.42 NM_133550 Fc receptor, IgE, low affinity II, alpha polypeptide Fcer2a 4.93 NM_031120 Signal sequence receptor, gamma Ssr3 4.84 NM_053544 Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 Sfrp4 4.73 NM_053910 Pleckstrin homology, Sec7 and coiled/coil domains 1 Pscd1 4.69 BE113233 Suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 Socs2 4.68 NM_053949 Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily H (eag- Kcnh2 4.60 related), member 2 NM_017305 Glutamate cysteine ligase, modifier subunit Gclm 4.59 NM_017309 Protein phospatase 3, regulatory subunit B, alpha Ppp3r1 4.54 isoform,type 1 NM_012765 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 2C Htr2c 4.46 NM_017218 V-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog Erbb3 4.42 3 (avian) AW918369 Zinc finger protein 191 Zfp191 4.38 NM_031034 Guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha 12 Gna12 4.38 NM_017020 Interleukin 6 receptor Il6r 4.37 AJ002942 -

Moldx : BCKDHB Gene Test

Local Coverage Article: Billing and Coding: MolDX: BCKDHB Gene Test (A55099) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01111 - MAC A J - E California - Entire State LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01112 - MAC B J - E California - Northern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01182 - MAC B J - E California - Southern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01211 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01212 - MAC B J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01311 - MAC A J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01312 - MAC B J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01911 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC California - Entire State Guam Hawaii Nevada Northern Mariana Islands Article Information General Information Article ID Original Effective Date Created on 12/19/2019. Page 1 of 6 A55099 10/17/2016 Article Title Revision Effective Date Billing and Coding: MolDX: BCKDHB Gene Test 12/01/2019 Article Type Revision Ending Date Billing and Coding N/A AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Retirement Date Statement N/A CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright 2018 American Medical Association. All Rights Reserved. Applicable FARS/HHSARS apply. Current Dental Terminology © 2018 American Dental Association. -

CENTOGENE's Severe and Early Onset Disorder Gene List

CENTOGENE’s severe and early onset disorder gene list USED IN PRENATAL WES ANALYSIS AND IDENTIFICATION OF “PATHOGENIC” AND “LIKELY PATHOGENIC” CENTOMD® VARIANTS IN NGS PRODUCTS The following gene list shows all genes assessed in prenatal WES tests or analysed for P/LP CentoMD® variants in NGS products after April 1st, 2020. For searching a single gene coverage, just use the search on www.centoportal.com AAAS, AARS1, AARS2, ABAT, ABCA12, ABCA3, ABCB11, ABCB4, ABCB7, ABCC6, ABCC8, ABCC9, ABCD1, ABCD4, ABHD12, ABHD5, ACACA, ACAD9, ACADM, ACADS, ACADVL, ACAN, ACAT1, ACE, ACO2, ACOX1, ACP5, ACSL4, ACTA1, ACTA2, ACTB, ACTG1, ACTL6B, ACTN2, ACVR2B, ACVRL1, ACY1, ADA, ADAM17, ADAMTS2, ADAMTSL2, ADAR, ADARB1, ADAT3, ADCY5, ADGRG1, ADGRG6, ADGRV1, ADK, ADNP, ADPRHL2, ADSL, AFF2, AFG3L2, AGA, AGK, AGL, AGPAT2, AGPS, AGRN, AGT, AGTPBP1, AGTR1, AGXT, AHCY, AHDC1, AHI1, AIFM1, AIMP1, AIPL1, AIRE, AK2, AKR1D1, AKT1, AKT2, AKT3, ALAD, ALDH18A1, ALDH1A3, ALDH3A2, ALDH4A1, ALDH5A1, ALDH6A1, ALDH7A1, ALDOA, ALDOB, ALG1, ALG11, ALG12, ALG13, ALG14, ALG2, ALG3, ALG6, ALG8, ALG9, ALMS1, ALOX12B, ALPL, ALS2, ALX3, ALX4, AMACR, AMER1, AMN, AMPD1, AMPD2, AMT, ANK2, ANK3, ANKH, ANKRD11, ANKS6, ANO10, ANO5, ANOS1, ANTXR1, ANTXR2, AP1B1, AP1S1, AP1S2, AP3B1, AP3B2, AP4B1, AP4E1, AP4M1, AP4S1, APC2, APTX, AR, ARCN1, ARFGEF2, ARG1, ARHGAP31, ARHGDIA, ARHGEF9, ARID1A, ARID1B, ARID2, ARL13B, ARL3, ARL6, ARL6IP1, ARMC4, ARMC9, ARSA, ARSB, ARSL, ARV1, ARX, ASAH1, ASCC1, ASH1L, ASL, ASNS, ASPA, ASPH, ASPM, ASS1, ASXL1, ASXL2, ASXL3, ATAD3A, ATCAY, ATIC, ATL1, ATM, ATOH7, -

Identifying Targetable Liabilities in Ewing Sarcoma

Identifying Targetable Liabilities in Ewing Sarcoma The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Vallurupalli, Mounica. 2014. Identifying Targetable Liabilities in Ewing Sarcoma. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard Medical School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12407620 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Abstract: Background: Despite multi-modality therapy, the majority of patients with metastatic or recurrent Ewing sarcoma (ES), the second most common pediatric bone malignancy, will die of their disease. ES tumors express aberrantly activated ETS transcription factors through translocations that fuse the EWS gene to ETS family genes FLI1 or ERG. The aberrant activation of ETS transcription factors promotes malignant transformation and proliferation. While, FLI1 or ERG cannot be readily targeted, there is an opportunity to deploy functional genomics screens, to develop novel therapeutic approaches by identifying targetable liabilities in EWS/FLI1 dependent tumors. Materials and Methods: We performed a near whole-genome pooled shRNA screen in a panel of five EWS/FLI1 dependent Ewing sarcoma cell lines and one EWS/ERG cell line to identify essential genes. Essential genes were defined as those genes whose loss resulted in reduced viability selectively in ES cells compared to non-Ewing cancer cell lines. Essential hits were subsequently validated with genomic knockdown and chemical inhibition in vitro, followed by validation of the on-target effect of chemical inhibition. -

(MSUD) in Malaysian Population

Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports 17 (2018) 22–30 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ymgmr Fourteen new mutations of BCKDHA, BCKDHB and DBT genes associated with maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) in Malaysian population T ⁎ ⁎ Ernie Zuraida Alia, , Lock-Hock Ngub, a Molecular Diagnostics and Protein Unit, Specialized Diagnostics Centre, Institute for Medical Research, Jalan Pahang, 50588 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. b Medical Genetics Department, Kuala Lumpur Hospital, Jalan Pahang, 50588 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) is a rare autosomal recessive metabolic disorder. This disorder is usually Maple syrup urine disease caused by mutations in any one of the genes; BCKDHA, BCKDHB and DBT, which represent E1α,E1β and E2 Autosomal recessive subunits of the branched-chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase (BCKDH) complex, respectively. This study presents Mutation the molecular characterization of 31 MSUD patients. Twenty one mutations including 14 new mutations were BCKDH identified. The BCKDHB gene was the most commonly affected (45.2%) compared to BCKDHA gene (16.1%) and BCAAs DBT gene (38.7%). In silico webservers predicted all mutations were disease-causing. In addition, structural MSUD evaluation disclosed that all new missenses in BCKDHA, BCKDHB and DBT genes affected stability and formation of E1 and E2 subunits. Majority of the patients had neonatal onset MSUD (26 of 31). Meanwhile, the new mutation; c.1196C > G (p.S399C) in DBT gene was noted to be recurrent and found in 9 patients. Conclusion: Our findings have expanded the mutational spectrum of the MSUD and revealed the genetic heterogeneity among Malaysian MSUD patients.