Salmacis, Hermaphrodite, and the Inversion of Gender: Allegorical Interpretations and Pictorial Representations of an Ovidian Myth, Ca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water, Women & Bodies in Ovid's Metamorphoses

Water, Women & Bodies in Ovid’s Metamorphoses Τhe ancient philosophers and scientists, in discussing gender differences, link women to wetness (τὸ ὑγρόν); Aristotle (Prob.809b12), Rufus (ap. Orib., Coll. Med. lib. inc. 20.1-2), Aretaeus (SA 2.12.4), Hippocrates (Mul. 1.1 viii 12.6-21) and Galen (Comp. Med. Gen. 2.1 xiii 467-8K) describe women as being naturally softer and wetter than men. While readers of Ovid’s Metamorphoses have noticed a connection between women and places of water (Salzman- Mitchell, 2005; Nugent, 1990; Parry, 1964), I suggest that the ancient scientific and philosophical works about women and their bodies cast light on the transformative property of water in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. I propose to consider how men and women deploy water in the Metamorphoses as a weapon against the opposite sex. In this context, water functions to emasculate men and to render women “more feminine”. In discussing the ancient physiological views, Anne Carson shows that women (like water) are soft and mollifying, porous and penetrable, formless and boundless. The most important and dangerous property that water and women share, however, is their pollutability; once they are polluted, they become polluting (Carson, 1990). Furthermore, women have a proclivity for overstepping and wreaking havoc on boundaries. This proclivity becomes even more dangerous when women are seen as watery and polluting bodies that contaminate and destroy gender boundaries. The Salmacis and Hermaphroditus story in the Metamorphoses (4.285-388) is one of the many episodes that clearly encapsulate the polluting and emasculating nature of a woman and her water (3.138-252; 5.439-461; 5.533-550; 6.317-381). -

And Type the TITLE of YOUR WORK in All Caps

IN CORPUS CORPORE TOTO: MERGING BODIES IN OVID’S METAMORPHOSES by JACLYN RENE FRIEND (Under the Direction of Sarah Spence) ABSTRACT Though Ovid presents readers of his Metamorphoses with countless episodes of lovers uniting in a temporary physical closeness, some of his characters find themselves so affected by their love that they become inseparably merged with the ones they desire. These scenarios of “merging bodies” recall Lucretius’ explanations of love in De Rerum Natura (IV.1030-1287) and Aristophanes’ speech on love from Plato’s Symposium (189c2-193d5). In this thesis, I examine specific episodes of merging bodies in the Metamorphoses and explore the verbal and conceptual parallels that intertextually connect these episodes with De Rerum Natura and the Symposium. I focus on Ovid’s stories of Narcissus (III.339-510), Pyramus and Thisbe (IV.55-166), Salmacis and Hermaphroditus (IV.276-388), and Baucis and Philemon (VIII.611-724). I also discuss Ovid’s “merging bodies” in terms of his ideas about poetic immortality. Finally, I consider whether ancient representations of Narcissus in the visual arts are indicative of Ovid’s poetic success in antiquity. INDEX WORDS: Ovid, Metamorphoses, Intertextuality, Lucretius, De Rerum Natura, Plato, Symposium, Narcissus, Pyramus, Thisbe, Salmacis, Hermaphroditus, Baucis, Philemon, Corpora, Immortality, Pompeii IN CORPUS CORPORE TOTO: MERGING BODIES IN OVID’S METAMORPHOSES by JACLYN RENE FRIEND B.A., Denison University, 2012 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2014 © 2014 Jaclyn Rene Friend All Rights Reserved IN CORPUS CORPORE TOTO: MERGING BODIES IN OVID’S METAMORPHOSES by JACLYN RENE FRIEND Major Professor: Sarah Spence Committee: Mark Abbe Naomi Norman Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. -

Reading the Presence of Both Male and Female Sex Organs

214 HORMONESG. 2006, ANDROUTSOS 5(3):214-217 Historical note Hermaphroditism in Greek and Roman antiquity George Androutsos Institute of History of Medicine, University Claude Bernard, Lyon, France ABSTRACT Since antiquity hermaphrodites have fascinated the mind and excited the imagination. In this paper, such subjects are discussed as legends about the nativity of Hermaphroditus, son of Hermes and Aphrodite, the social status of these bisexual beings, and their fate in Greek- Roman antiquity. Key words: Female pseudohermaphroditism, Hermaphroditism, Male pseudohermaphroditism. INTRODUCTION The cult of the dual being is also to be found amongst the numerous arcane sciences of the mys- Hermaphroditism is a state characterized by tical religions of Hindu peoples, before spreading the presence of both male and female sex organs. through Syria to Cyprus, and then into Greece. Here Recent developments in the understanding of the it degenerated and met the same fate as the hyste- pathogenetic mechanisms involved in defective sex- ro-phallic cults. During such times of decadence, ual differentiation and the social repercussions of hermaphroditism was looked upon as the embodi- the term hermaphrodite have created the need for ment of sexual excess, while for philosophers, it rep- new terminology. Hence, such disorders are today resented the twofold nature of the human being, designated as genetic defects in the differentiation considered as the original being.3 of the genital system.1 HERMAPHRODITES IN ANCIENT GREECE THE FORERUNNERS Greek mythology abounds in examples of such Beings that are simultaneously both male and dual beings. Even the gods themselves were often female have stirred the human imagination since hermaphrodites: Dyalos, the androgyne; Arse- ancient times. -

Theocritean Hermaphroditus: Ovid’S Protean Allusions in Met

Theocritean Hermaphroditus: Ovid’s Protean Allusions in Met. 4.285-388 The presence of thematic and visual resonances in the myths of Hylas and Hermaphroditus suggests that Ovid uses Theocritus’ Id. 13 as an intertext, as many scholars have previously argued (see Charles Segal, Matthew Robinson, and Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood). In my paper, I explore how Ovid transforms Theocritus’ Hylas myth into a new, distinct story: the Hermaphroditus myth (Met. 4). I argue that Ovid’s references to Id. 13 go far deeper than “comparabilities” between the “nympholeptoi,” both of whom are grabbed and fall into water at similar points in the narrative (Sourvinou-Inwood 2005). Rather, Ovid’s recharacterization of the nymph Salmacis from kourotrophic guardian to sexual predator, as well as the assault on Hermaphroditus and consequential loss of “his” voice, distinctly echo the abduction of Hylas by the Kian nymphs. This suggests, then, that Ovid deliberately omits the Hylas tale later in the Metamorphoses in order to fuse it with his own innovative bucolic myth. In order to examine Theocritus’ influence on Ovid, I will conduct a comparative study between selected passages. First, I will draw parallels between the sexualization of Herakles’ caretaker role (Id. 13.5-11) and the maternal overtones in the Kian nymphs’ rape of Hylas (Id. 13.47-54.). I will then compare these details to Ovid’s depiction of Salmacis as a sexually voracious nymph (Met. 4.288-95), a revision of her kourotrophic origin in the Salmacis Inscription (a Hellenistic inscription that identifies Hermaphroditus as a κοῦρος, whose wet nurse was Salmacis [Groves 2016; Sourvinou-Inwood 2005]). -

PP Autumn 2013.Indd

Leadership of Women in Crete and Macedonia as a Model for the Church Aída Besançon Spencer A superficial glance at the New Testament in translation, com- teaching positions versus unofficial teaching, nor does it seem bined with an expectation of a subordinate role for women, re- to be an issue of subject matter. sults in generalizations that Paul commands women not to teach These sorts of modern categories are not apt for describing or have authority (1 Tim 2:11–15), except in the case of older wom- a church that met in a home in which the family and family- en teaching younger women how to be housewives (Titus 2:3–5), of-faith structures and the public and the private spheres and women are not to teach in official, public, formal positions in overlapped in the home-worship events. Paul does not the church, but they can teach in informal, private, one-on-one complain that the false teachers are not appointed teachers; situations in the home.1 rather, he complains that they are offering false teaching. It is However, a deeper search into the New Testament reveals a important, then, not to misread the social context in which dissonance with those interpretations. In 1 Timothy 2:12, Paul early Christian teaching transpired on Crete and elsewhere.5 writes, “I do not permit a woman to teach,” but, in Titus 2:3, Paul expects the “older women” to teach. Paul uses the same root word Many egalitarians have argued that 1 Timothy 2:11–15 needs to for men as for women teaching, didaskō. -

Derrida's Salmacis: the Phallogocentrism in Ovid's

Derrida’s Salmacis: the Phallogocentrism in Ovid’s Metamorphoses 4.285-300 The aetiology of the Salmacis spring, as told by Alcithoë (Ovid Met. 4.285-388), reveals the bizarre agency behind the spring’s enervating properties. The role of the nymph Salmacis as an elegiac amator, rather than the desired object, provides an excellent example of phallogocentric narrative as prescribed by Derrida’s theoretical model. Derrida’s theory on phallogocentrism deals with the linguistic and cultural demarcation between what is masculine (unmarked) and feminine (marked). Derrida allocates logocentrism to “a Platonic schema that assigns the origin and power of speech, precisely of logos, to the paternal position” (Derrida- 1981: p.76). Salmacis, on the other hand, resists this platonic schema when Ovid portrays her as the elegaic amator. To examine the depiction of Salmacis as the elegiac amator, I will compare the Salmacis story with various rape scenes in the Metamorphoses, particularly the vocabulary used by the rapist which Salmacis incorporates in her own speech. Next, I will explore an intertextual relationship between the Salmacis story and Ovid’s Amores 1.3 and 1.5. To understand how Salmacis the amator uses a paternal logos, I will compare her to Ovid’s amator of the Amores. For example, the speech Salmacis delivers to Hermaphroditus echoes some aspects of Amores 1.3; while the description of the desired object, Corinna, in Amores 1.5, resembles Ovid’s characterization of Hermaphroditus in the Metamorphoses. I will also demonstrate how the flattery used by Salmacis recalls Odysseus’ flattery of Nausicaä (Homer Od. -

Dionysiac Art and Pastoral Escapism

Alpenglow: Binghamton University Undergraduate Journal of Research and Creative Activity Volume 6 Number 1 (2020) Article 4 12-1-2020 Dionysiac Art and Pastoral Escapism Casey Roth Binghamton University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/alpenglowjournal Recommended Citation Roth, C. (2020). Dionysiac Art and Pastoral Escapism. Alpenglow: Binghamton University Undergraduate Journal of Research and Creative Activity, 6(1). Retrieved from https://orb.binghamton.edu/ alpenglowjournal/vol6/iss1/4 This Academic Paper is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Alpenglow: Binghamton University Undergraduate Journal of Research and Creative Activity by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Casey Roth Dionysiac Art and Pastoral Escapism The pastoral lifestyle was appealing to many people in the Hellenistic and Roman world, as it provided an escape from the stresses of the city.1 This longing to flee the materialistic urban centers was reflected in art and literature, in which Dionysiac figures, such as satyrs or even herdsmen, were represented and described in this idealized environment and provided viewers with a sense of being carefree. Dionysiac elements in art and literature represented this escape from the chaotic city, overcoming boundaries to allow one to welcome a utopia.2 Not only were boundaries overcome in both a worldly and geographic sense, but also identity was challenged. As a result of escaping the city through pastoralism, one could abandon their identity as a civilian for an existence defined by pastoral bliss.3 Pastoralism was associated with an idyllic landscape and can act as an escape from reality. -

Ovidian Transversions Series Editors: Paul Yachnin and Bronwen Wilson

CONVERSIONS OVIDIAN TRANSVERSIONS OVIDIAN SERIES EDITORS: PAUL YACHNIN AND BRONWEN WILSON ‘A spectacular achievement. Harnessing the capacity of Ovid’s 1300–1650 AND IANTHE’, ‘IPHIS Iphis story to unsettle our categories of being and knowing, this book represents the very best in collaborative scholarship. It makes a truly transformational contribution to research on Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Ovidian reception, and the history and politics of embodiment, sexuality and gender.’ Robert Mills, University College London Focuses on transversions of Ovid’s ‘Iphis and Ianthe’ in both English and French literature Medieval and early modern authors engaged with Ovid’s tale of ‘Iphis and Ianthe’ in a number of surprising ways. From Christian translations to secular retellings on the seventeenth-century stage, Ovid’s story of a girl’s miraculous transformation into a boy sparked a diversity of responses in English and French from the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries. In addition to analysing various translations and commentaries, the volume clusters essays around treatments of John Lyly’s Galatea (c.1585) and Issac de Benserade’s Iphis et Iante (1637). As a whole, the volume addresses gender and transgender, sexuality and gallantry, anatomy and alchemy, fable and history, youth and pedagogy, language and climate change. Badir and Peggy McCracken Patricia VALERIE TRAUB is author of Thinking Sex with the Early Moderns. Traub, Edited Valerie by PATRICIA BADIR is author of The Maudlin Impression: English Literary Images of Mary Magdalene, 1550–1700. PEGGY MCCRACKEN is author of In the Skin of a Beast: Sovereignty and Animality in Medieval France. OVIDIAN TRANSVERSIONS Cover image: Metamorphosis of Ovid; plaster statuette by Auguste Rodin; ca. -

God Is Transgender

GOD IS TRANSGENDER In what was an intellectual high for the New York Times, the Gray Lady printed an op- ed article titled “Is God Transgender?” by a New York rabbi named Mark Sameth. Related to a man who “transitioned to a woman” in the 1970s, Sameth contends that “the Hebrew Bible, when read in its original language, offers a highly flexible view of gender.” He puts forward many historical examples of gender fluidity in the Hebrew scriptures, in order to maintain that religion should not be put in service of “social prejudices” against transgendering. His treatment of the Bible amounts to excellent scholarship. Proposing that the God of Israel was worshipped originally as “a dual-gendered deity,” the rabbi asserts, that the etymological derivation of Yahweh is “He/She” (HUHI). His argument requires that the Tetragrammaton be read, not from right to left (as Hebrew always is), but from left to right: The four-Hebrew-letter name of God, which scholars refer to as the Tetragrammaton, YHWH, was probably not pronounced “Jehovah” or “Yahweh,” as some have guessed. The Israelite priests would have read the letters in reverse as Hu/Hi—in other words, the hidden name of God was Hebrew for “He/She.” Some biblical scholars say that “Yahweh” is derived from the third-person singular of the verb “to be” (hayah), whether a qal imperfect (“he is” or “he will be”) or the causative hiphil imperfect (“he causes to come into being, he creates”). This view is confirmed by numerous lines of evidence: the interpretation given in Exod 3:14 (“Say to the sons of Israel, ‘ehyeh [‘I am’ or ‘I will be’ (who I am/will be)] sent me to you”); the use of shortened forms of Yahweh at the end (“Yah” or “Yahu”) or beginning (“Yeho” or “Yo”) of Hebrew names; the spelling “Yabe” known to the Samaritans; and transliterations “Yao,” “Ya-ou-e,” and “Ya-ou-ai” in some Greek texts. -

Speech, Silence, and Gender in the Hermaphroditus Myth of Ovid’S Metamorphoses (4.274-388)

Speech, Silence, and Gender in the Hermaphroditus Myth of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (4.274-388) In this paper, I analyze the Salmacis and Hermaphroditus myth in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (4.274-388) in terms of direct speech and explicit references to silence for both of the principal characters. I argue that Ovid uses direct speech to empower both the aggressor Salmacis and the victim Hermaphroditus; in the former case, speech serves to align Salmacis with other rapists and aggressors throughout the Metamorphoses and characterize her negatively, while in the latter case, Hermaphroditus’ speech enables him to resist Salmacis’ advances, at least initially, and ends the narrative proper, a fact that allows Hermaphroditus the last word, as it were. Silence, on the other hand, serves in Salmacis’ case as a rhetorical tool to gain the upper hand (4.329 and 4.338-340), but in Hermaphroditus’ case, the narrator Alcithoë mostly prevents Hermaphroditus from speaking to emphasize the visual allure of his body and his victimhood. While previous scholarship on the episode has focused on such considerations as Salmacis’ appropriation of the male gaze, the subversion of “traditional” gender roles, and the iconographic and literary representations of Salmacis and Hermaphroditus prior to Ovid (Salzman-Mitchell 2005, 160- 163; Keith 1999, 216-221; Nagle 1984, 248-252; Robinson 1999, passim), this paper expands the existing scholarship by focusing on the role of speech and silence in the episode in the constitution of each character, Salmacis as a gender-defying rapist and Hermaphroditus as an empowered, recalcitrant male victim. Salmacis speaks directly four times in the narrative: 4.320-328, to proposition Hermaphroditus; 4.337-338, to feign a departure to mollify Hermaphroditus; 4.356, to declare victory; and 4.370-372, to taunt Hermaphroditus as he tries to escape and to pray to the gods that they be joined together. -

Diving Into SALMACIS' POOL of GENDER Ambiguity

DIVING INTO SALMACIS’ POOL OF GENDER AMBIGUITY An examination of the representation of gender roles in the Salmacis and Hermaphroditus scene in Ovid’s Metamorphoses By: T.J. de Vries, S1096273 Supervisor: Prof. dr. I. Sluiter 11-08-2020 Master Thesis Classics and Ancient Civilizations Faculty of Humanities, Leiden University Wordcount (including notes, bibliography and appendix): 14988 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 1 – Analysis of the Salmacis & Hermaphroditus-scene (Met. 4.285-388) ................................. 5 1.1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2. Context ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.3. Running commentary ................................................................................................................... 5 1.3.1 Abstract (4.285-287) ............................................................................................................... 5 1.3.2. Orientation (4.288-315)......................................................................................................... 6 1.3.3. First complication, peak and resolution (4.315-340): First meeting ................................... 10 1.3.4. Second complication, peak and resolution: the attack -

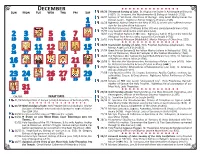

December · · · · · · · · · · · · · · Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 09/26 Thirteenth Sunday of Luke

December · · · · · · · · · · · · · · Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 09/26 Thirteenth Sunday of Luke. St. Alypius the Stylite in Adrianople of Bithynia (+607). St. Innocent, the Wonderworker & Bishop of Irkutsk (+1731). 10/27 Synaxis of Ϻϴ Kursk - Root Icon of the Sign. Holy Great Martyr James the Persian (+421). Righteous Father Gregory of Sinai (+1346). 1 11/28 Righteous Martyr Stephen the New (+767) & others who suffered martyr- 18 dom for the sake of the holy icons. 12/29 Martyr Paramonus of Bithynia & the 370 who contested with him (+250). 13/30 Holy Apostle Andrew the First Called (+62). 14/01 Holy Prophet Nahum (+7th C BC). Righteous Father Philaret the Merciful 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Almsgiver from Amneia who reposed in Con/nople (+792). 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 15/02 Holy Prophet Abbacum (Habakkuk). Martyr Myrope of Chios (+ca. 250). · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 16/03 Fourteenth Sunday of Luke. Holy Prophet Sophonias (Zephaniah). New Martyr Angelis of Chios (+1813). 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 17/04 Great Martyr Barbara & her fellow Martyr Juliana in Heliopolis (+290). St. 26 27 28 29 30 1 2 John of Damascus, Monk & Presbyter of Mar Sabbas Monastery (+760). 18/05 Our Righteous Mar Sabbas the Sanctified of Palestine (+533). St. Nectarius of Karyes on Mount Athos (+1500). 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 19/06 St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, Archbishop of Myra in Lycia (+330). Mar- tyr Victoria slain by the Arians of Culusi in Africa (+4th C). 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 20/07 Righteous Martyr Athenodorus of Mesopotamia (+ca.