Once Upon a Time Saints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

St. Mary & Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church Houston, Texas

A Glimpse Into The Coptic World Presented by: St. Mary & Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church Houston, Texas www.stmaryhouston.org © St. Mary & Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church, Houston, TX Slide 1 A Glimpse Into The Coptic World © St. Mary & Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church, Houston, TX © St. Mary & Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church, Houston, TX Slide 2 HI KA PTAH © St. Mary & Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church, Houston, TX The word COPT is derived from the ancient Egyptian word HI KA PTAH meaning house of spirit of PTAH. According to ancient Egyptians, PTAH was the god who molded people out of clay and gave them the breath of life; This believe relates to the original creation of man. The Greeks changed the name of “HI KA PTAH “ to Ai-gypt-ios. © St. Mary & Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church, Houston, TX Slide 3 © St. Mary & ArchangelAncient Michael Coptic Egypt Orthodox Church, Houston, TX The Arabs called Egypt DAR EL GYPT which means house of GYPT; changing the letter g to q in writing. Originally all Egyptians were called GYPT or QYPT, but after Islam entered Egypt in the seventh century, the word became synonymous with Christian Egyptians. According to tradition, the word MISR is derived from MIZRA-IM who was the son of HAM son of NOAH It was MIZRA-IM and his descendants who populated the land of Egypt. © St. Mary & Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church, Houston, TX Slide 4 © St. Mary The& Archangel Coptic Michael Coptic language Orthodox Church, Houston, TX The Coptic language and writing is the last form of the ancient Egyptian language, the first being Hieroglyphics, Heratic and lastly Demotic. -

SAINT JOHN the BAPTIST ROMAN CATHOLIC PARISH 10 January

SAINT JOHN THE BAPTIST ROMAN CATHOLIC PARISH SERVING THE MISSIONS OF SAINT ALBERT THE GREAT AND SAINT MARY QUEEN OF HEAVEN 10 January 2021 Baptism of the Lord MASS SCHEDULE ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST (SJB) 16680 Main St Sat, 09 Jan Baptism of the Lord Frenchtown, MT 59834 4:00 pm (MQH) No Mass ST. ALBERT THE GREAT (SAG) 117 Railroad St Sun, 10 Jan Baptism of the Lord Alberton, MT 59820 8:30 am (SJB) Pro Populo ST. MARY QUEEN OF HEAVEN (MQH) Wed, 13 Jan Saint Hilary of Poitiers 204 2nd Ave E 11:00 am (SJB) Mike Dunn Superior, MT 59872 Fri, 15 Jan Weekday 11:00 am (SJB) Souls in Purgatory CONFESSIONS SICK CALLS Weekends Fifteen minutes before Mass. Call the parish office if you would like a home visit for the (and by appointment) Sacraments. ADORATION OF THE BLESSED SACRAMENT If you have a sacramental emergency outside of office hours, please call 406.202.8912. Wednesday 10:00 am (Frenchtown) Friday 10:00 am (Frenchtown) PARISH OFFICE THE HOLY ROSARY Hours: TWThF – 9:00 am to 4:30 pm Weekends Twenty minutes before Mass. Mailing Address PO Box 329 Frenchtown, MT 59834-0329 Phone and Fax 406.626.4492 Email [email protected] Website www.clarkforkcatholic.com Fr. David Severson Pastor [email protected] Bridgette Bannick Office Manager [email protected] LITURGICAL CALENDAR THIS WEEK WE CELEBRATE: St. Theodosius, Abbot (Optional Memorial) 11 Jan Weekday St. Hyginus; St. Paulinus; St. Theodosius “St. Theodosius was so inspired by Abraham’s example Heb 1:1–6 / Mt 1:14–20 of leaving his loved ones and homeland for God that he left his homeland of Cappadocia to make a pilgrimage to 12 Jan Weekday Jerusalem. -

African Roots of Christianity: Christianity Is a Religion of Africa

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Faculty Publications 2021 African Roots of Christianity: Christianity is a Religion of Africa Trevor O'Reggio Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/pubs Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation O'Reggio, Trevor, "African Roots of Christianity: Christianity is a Religion of Africa" (2021). Faculty Publications. 2255. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/pubs/2255 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. African Roots of Christianity CHRISTIANITY IS A RELIGION OF AFRICA African Proverb We must go back and reclaim our past, so that we can move forward, so we can understand why and how we came to be who we are today Ancient Akan principle of Sankofa Early Christianity Christianity in the 3rd.century Christianity in Africa 250-AD-406-AD Christianity in Transition The era of Western Christianity has passed within our lifetime and the day of Southern Christianity is dawning. The fact of change is undeniable; it has happened and will continue to happen. Phillip Jenkins Shifting Christianity 1500—Era of Luther and Calvin • 92% of Christians were in global north • Christianity was a “white man’s religion” 1800—William Carey to India • 86% of Christians were in global north 1900—82% in north 2000—42% in north, 58% in south • Christianity is a world religion 2100—22% in north, 78% in south (proj. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Guarino

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Guarino Guarini: His Architecture and the Sublime A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Carol Ann Goetting June 2012 Thesis Committee: Dr. Kristoffer Neville, Chairperson Dr. Jeanette Kohl Dr. Conrad Rudolph Copyright by Carol Ann Goetting 2012 The Thesis of Carol Ann Goetting is approved: ______________________________________ ______________________________________ ______________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the financial support of the University of California, Riverside and the Gluck Fellows Program of the Arts which enabled me to conduct primary research in Italy. Words cannot express enough the gratitude I feel towards my advisor Dr. Kristoffer Neville whose enthusiasm, guidance, knowledge and support made this thesis a reality. He encouraged me to think in ways I would have never dared to before. His wisdom has never failed to amaze me. I was first introduced to the work of Guarino Guarini in his undergraduate Baroque Art class, an intriguing puzzle that continues to fascinate me. I am also grateful for the help and encouragement of Drs. Conrad Rudolph and Jeanette Kohl, whose dedication and passion to art history has served as an inspiration and model for me. I am fortune to have such knowledgeable and generous scholars share with me their immense knowledge. Additionally, I would like to thank several other faculty members in UCR’s History of Art department: Dr. Jason Weems for giving me an in-depth understanding of the sublime which started me down this path, Dr. -

'The Mystic Drum': Critical Commentary on Gabriel Okara's

University of Massachusetts Boston From the SelectedWorks of Chukwuma Azuonye 2011 ‘The ysM tic Drum’: Critical Commentary on Gabriel Okara’s Love Lyrics Chukwuma Azuonye, University of Massachusetts Boston Available at: https://works.bepress.com/chukwuma_azuonye/82/ ‘The Mystic Drum’: Critical Commentary on Gabriel Okara’s Love Lyrics: By Chukwuma Azuonye, PhD Professor of African & African Diaspora Literatures University of Massachusetts Boston Introduction In the course of reading a chapter entitled “Empty and Marvelous” in Alan Watts fascinating book, The Way of Zen (1957), a serendipitous key was provided, by the following statement from the teachings of Chinese Zen master,1 Ch’ing Yuän Wei-hsin (1067-1120), to the structure and meaning of the experience dramatized in Gabriel Okara’s most famous love poem, “The Mystic Drum”: 2 Before I had studied Zen for thirty years, I saw mountains as mountains and waters as waters. When I arrived at a more intimate knowledge, I came to the point where I saw the mountains are not mountains, and waters are not waters. But now that I have got its very substance I am at rest. For it’s just now that I see mountains once again as mountains and waters once again as waters. What is so readily striking to anyone who has read “The Mystic Drum” is the near perfect dynamic equivalence between the words of Ch’ing Yuän and the phraseology of Okara’s lyric. In line with Ch’ing Yuän’s statement, the lyric falls into three clearly defined parts—an initial phase of “conventional knowledge,” when men are men and fishes are fishes (lines 1-15); a median phase of “more intimate knowledge,” when men are no longer men and fishes are no longer fishes (lines 16-26); and a final phase of “substantial knowledge,” when men are once again men and fishes are once again fishes, with the difference that at this phase, the beloved lady of the lyric is depicted as “standing behind a tree” with “her lips parted in her smile,” now “turned cavity belching darkness” (lines 27-41). -

Jn 18:1-19:42

GOOD FRIDAY Is 52:13-53:12; Ps 31:2,6,12-13,15-16,17,25; Heb 4:14-16; 5:7-9; Jn 18:1-19:42 IMMEDIATELY BLOOD AND WATER FLOWED OUT Homily by Fr. Michael A. Van Sloun Friday, March 30, 2018, 7:00 p.m. I have the name of a saint that is not very well known. Maybe you have heard about him. Maybe, probably not. His name is St. Longinus. For most of my life, I had never heard of St. Longinus. I made my first trip to Rome when I was a theology student. If a Catholic goes to Rome, a visit to St. Peter’s Vatican Basilica is a must. I entered the basilica and went to the high altar. It is under a beautiful canopy, the baldachino. It is where the Pope says Mass, like tomorrow for the Easter Vigil. It is above the tomb of St. Peter the apostle which is on the lower level. There are four huge statues around the altar. Of course, I went to take a picture of each of them. Two of them are women: St. Helena and St. Veronica. The other two are men: St. Andrew and St. Longinus. St. Longinus! Who is he? Why is this guy that I have never heard of get such a prominent place in the most important church of our faith? It was time to look for clues. Why these saints? St. Helena found the True Cross. St. Veronica wiped the face of Jesus when he was on the Way of the Cross. -

Confirmation

CONFIRMATION December 1, 2020 Dear Parents and Students, You have elected to register your son/daughter for the St. Agnes Christian Formation program this year. When registering your son/daughter it is stated that our Confirmation program is a two-year program. This program challenges him or her to grow in his or her understanding of the Catholic faith and his or her personal relationship with God. There are several points to make you aware of in preparation for Confirmation (which starts in 8th grade with the student receiving the Sacrament with the completion of 9th grade studies) (due to pandemic this school year completion of 10th grade)). Successful completion of the curriculum includes once a month catechesis, service to others, and spending time with God in prayer. The greatest form of prayer is the celebration of the Mass. As Catholics, we are encouraged to attend weekly Mass in order to recognize God’s love more fully in the Word and Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist. While the pandemic poses a particular challenge at this time, students and their families are highly encouraged to either attend weekly Mass in person (Precautions are in place to ensure everyone’s safety) or to seek out an online Mass to encourage growth in love for Christ in preparation for Confirmation. Below is a list of other expectations. Remember, these “assignments” are designed to support our students in their desire to know, love, and serve our wonderful God while helping to prepare them for the reception of the Sacrament. This process for being Confirmed in the Spirit is a commitment from the parish, support from parents, and a commitment from the student that wishes to be Confirmed. -

SYNAXARION, COPTO-ARABIC, List of Saints Used in the Coptic Church

(CE:2171b-2190a) SYNAXARION, COPTO-ARABIC, list of saints used in the Coptic church. [This entry consists of two articles, Editions of the Synaxarion and The List of Saints.] Editions of the Synaxarion This book, which has become a liturgical book, is very important for the history of the Coptic church. It appears in two forms: the recension from Lower Egypt, which is the quasi-official book of the Coptic church from Alexandria to Aswan, and the recension from Upper Egypt. Egypt has long preserved this separation into two Egypts, Upper and Lower, and this division was translated into daily life through different usages, and in particular through different religious books. This book is the result of various endeavors, of which the Synaxarion itself speaks, for it mentions different usages here or there. It poses several questions that we cannot answer with any certainty: Who compiled the Synaxarion, and who was the first to take the initiative? Who made the final revision, and where was it done? It seems evident that the intention was to compile this book for the Coptic church in imitation of the Greek list of saints, and that the author or authors drew their inspiration from that work, for several notices are obviously taken from the Synaxarion called that of Constantinople. The reader may have recourse to several editions or translations, each of which has its advantages and its disadvantages. Let us take them in chronological order. The oldest translation (German) is that of the great German Arabist F. Wüstenfeld, who produced the edition with a German translation of part of al-Maqrizi's Khitat, concerning the Coptic church, under the title Macrizi's Geschichte der Copten (Göttingen, 1845). -

3Rd Sunday of Great Lent – Veneration of the Holy Cross Commemoration of the Hieromartyr Basil, Priest of Ancyra (362 AD)

St. Nicholas Orthodox Church Main Street Sixth Street Jacobs Creek, Pa. Monongahela, Pa. Very Rev. Edward Pehanich www. orthodoxmon.org 724-863-3741 [email protected] 412-651-2587 c April 4, 2021 3rd Sunday of Great Lent – Veneration of the Holy Cross Commemoration of the Hieromartyr Basil, priest of Ancyra (362 AD) This Week: TUESDAY – 5:30 p.m. VESPERAL DIVINE LITURGY WEDNESDAY – Great Feast of the Annunciation FRIDAY – 5:30 p.m. The Annunciation, also referred to as PRESANCITIFED LITURGY the Annunciation to the Blessed Virgin & All Souls Panachida Mary, or the Annunciation of the Lord, (Jacobs Creek) is the celebration of the announcement by the Archangel Gabriel to the Blessed Virgin Mary that she would conceive and become the mother of Jesus, the Jewish messiah and Son of God, schedule and the links to join the Event marking His Incarnation. Gabriel told will be sent to you. Mary to name her son Jesus. At that time a momentous event in the history of the world took place: God began to Remember in prayer Pani Donna take on human form in the womb of the Smoley who is undergoing surgery at Theotokos. the Cleveland Clinic on Wednesday. _______________________ Attention youth The next “The Vine Paska Place your order for Paska and and the Branches” online Diocesan horseradish from the Ladies Guild by Youth event for youth ages 5-18 signing the order form on the bulletin (Kindergarten up to 12th Grade board. currently) is scheduled for Sunday, April 11, 2021 at 6pm. His Eminence Metropolitan Gregory is calling all our Collection We continue to collect youth ages 5-18 to come together again items for the Neighborhood online on April 11 in order to strengthen Resilience Project (formerly known as their faith and connect with their peers FOCUS) and St. -

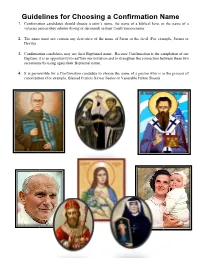

Guidelines for Choosing a Confirmation Name 1

Guidelines for Choosing a Confirmation Name 1. Confirmation candidates should choose a saint’s name, the name of a biblical hero, or the name of a virtuous person they admire (living or deceased) as their Confirmation name. 2. The name must not contain any derivative of the name of Satan or the devil (For example, Satana or Devila). 3. Confirmation candidates may use their Baptismal name. Because Confirmation is the completion of our Baptism, it is an opportunity to reaffirm our initiation and to strengthen the connection between these two sacraments by using again their Baptismal name. 4. It is permissible for a Confirmation candidate to choose the name of a person who is in the process of canonization (For example, Blessed Francis Xavier Seelos or Venerable Fulton Sheen) CHOOSING A CONFIRMATION SAINT We choose a Confirmation saint because we realize how unfortunate it would be to travel alone. The saints have so much to teach us about this journey. The following list is for you to use as a starting point to assist your child in choosing a “Confirmation saint-buddy.” Have your child pick a saint who speaks to them. Know their story, but mostly know the power of their prayer to this saint. Encourage your child to include praying to this saint as part of their prayer life. I) “Superhero” Saints! The “superpowers” of these saints were not the result of a scientific accident or alien power. These people were simply receptive to the mighty power of God. These following saint stories are incredibly heroic! St. Mary, the Mother of God St. -

Saint Michael the Archangel Orthodox Church

Saint Michael the Archangel Orthodox Church 146 Third Avenue, Rankin, PA 15104 Pastor: Very Reverend Nicholas Ferencz, PhD Cantor: Professor Jerry Jumba Parish President : Carole Bushak Glory to Jesus Christ! Glory Forever! Slava Isusu Christu! Slava vo v’iki! Rectory Phone: 412 271-2725. E-mail: [email protected] Hall Phone: 412-294-7952 WEB: www.stmichaelsrankin.org OCTOBER 25, 2020 20TH SUNDAY AFTER PENTECOST 3RD SUNDAY OF LUKE Sun., Oct. 25 20th Sunday after Pentecost. 3rd Sunday of Luke. Fathers of the 7th Ecumenical Council. Martyrs Probus et al. Bishop Martin of Tours 9:00 AM Divine Liturgy. Sun., Nov. 1 21st Sunday after Pentecost. 4th Sunday of Luke. Prophet Joel. Martyr Varus 9:00 AM Divine Liturgy. Tone 4 pp 105–107 Sun., Nov. 8 22nd Sunday after Pentecost. 5th Sunday of Luke. Great-Martyr Demetrius 9:00 AM Divine Liturgy. Panachida: November Perpetual Remembrances: 11/1 Mary Buddy. John & Helen Kosko. 11/3 Mary Moticsko. Anna Moticsko. 11/11 Frank, Mary and George Zubeck. 11/22 Eleanor Vaskov. 11/27 Andrew Bonga, Sr. 11/29 Nicholas Duranko, Sr. 11/30 Vasil (William) Vaskov. Holy Mystery of Confession: I will be available for Confessions after the Divine Liturgy, when the church is more private. Or, you can make an appointment and we will arrange an appropriate time. Please just contact me. PEOPLE STUFF Prayer List: Deceased: Mary Chakos Living: Father George Livanos. Father Patrick. Mother Christophora and the nuns of Holy Transfiguration Monastery. Dana Andrade. Gloria Andrade. Gregory Michael Aurilio. Georgia B. Chastity and Jeff Bache. Brandon. Walter Bolbat.