Sakhipur, Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangladesh, Year 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED)

BANGLADESH, YEAR 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 29 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; China/India border status: CIA, 2006; geodata of disputed borders: GADM, November 2015b; Natural Earth, undated; incident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 BANGLADESH, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 29 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Protests 930 1 1 Conflict incidents by category 2 Riots 405 107 122 Development of conflict incidents from 2010 to 2019 2 Violence against civilians 257 184 195 Battles 99 43 63 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 15 0 0 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 7 2 2 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 1713 337 383 Disclaimer 6 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2010 to 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 BANGLADESH, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 29 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. -

List of Pourashava (Division and Category Wise)

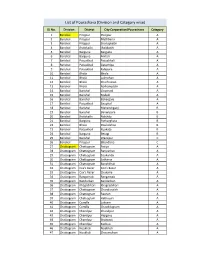

List of Pourashava (Division and Category wise) SL No. Division District City Corporation/Pourashava Category 1 Barishal Pirojpur Pirojpur A 2 Barishal Pirojpur Mathbaria A 3 Barishal Pirojpur Shorupkathi A 4 Barishal Jhalokathi Jhalakathi A 5 Barishal Barguna Barguna A 6 Barishal Barguna Amtali A 7 Barishal Patuakhali Patuakhali A 8 Barishal Patuakhali Galachipa A 9 Barishal Patuakhali Kalapara A 10 Barishal Bhola Bhola A 11 Barishal Bhola Lalmohan A 12 Barishal Bhola Charfession A 13 Barishal Bhola Borhanuddin A 14 Barishal Barishal Gournadi A 15 Barishal Barishal Muladi A 16 Barishal Barishal Bakerganj A 17 Barishal Patuakhali Bauphal A 18 Barishal Barishal Mehendiganj B 19 Barishal Barishal Banaripara B 20 Barishal Jhalokathi Nalchity B 21 Barishal Barguna Patharghata B 22 Barishal Bhola Doulatkhan B 23 Barishal Patuakhali Kuakata B 24 Barishal Barguna Betagi B 25 Barishal Barishal Wazirpur C 26 Barishal Pirojpur Bhandaria C 27 Chattogram Chattogram Patiya A 28 Chattogram Chattogram Bariyarhat A 29 Chattogram Chattogram Sitakunda A 30 Chattogram Chattogram Satkania A 31 Chattogram Chattogram Banshkhali A 32 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Cox’s Bazar A 33 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Chakaria A 34 Chattogram Rangamati Rangamati A 35 Chattogram Bandarban Bandarban A 36 Chattogram Khagrchhari Khagrachhari A 37 Chattogram Chattogram Chandanaish A 38 Chattogram Chattogram Raozan A 39 Chattogram Chattogram Hathazari A 40 Chattogram Cumilla Laksam A 41 Chattogram Cumilla Chauddagram A 42 Chattogram Chandpur Chandpur A 43 Chattogram Chandpur Hajiganj A -

Evaluation of Netherlands-Funded Ngos in Bangladesh

Evaluation of Netherlands-funded NGOs in Bangladesh Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Policy and Operations Evaluation Department (IOB) ISBN 90-5328-163-0 Photographs: Ron Giling/LINEAIR Maps and figures: Geografiek, Amsterdam Pre-press services: Transcripta, Beerzerveld Printed by: Ridderprint BV, Ridderkerk Preface The evaluation of Netherlands supported NGOs in Bangladesh forms part of a study undertaken by the Policy and Operations Evaluation Department (IOB) on the Netherlands bi-lateral aid programme for Bangladesh in the period 1972–96. The support to NGOs through the regular aid programme and through the Co-financing Programme has been important to the Netherlands’ pursuance of poverty alleviation objectives in Bangladesh. A total of Dfl. .247 million has been disbursed through these channels, some three quarters of which after 1990. The position of NGOs in Bangladeshi society is quite unique. Bangladesh is home to the largest national NGOs in the world, as well as to a multitude of middle- and small-sized NGOs that operate on a national, regional or local level. The Bangladeshi NGOs literally reach out to millions of people in both rural and urban areas. This study comprises extensive case studies of a cross section of NGOs in Bangladesh. Both the Bangladeshi NGOs that were subject of study and their partners in the Netherlands, Bilance (formerly Cebemo), ICCO and Novib, have been closely involved in the various stages of the study. The study has concentrated on the credit and training activities that constitute the mainstay of NGO programmes. It is concluded that these activities effectively target the poorer sections of the population, particularly women. -

Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 10 04 10 04

Geo Code list (upto upazila) of Bangladesh As On March, 2013 Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 BARISAL DIVISION 10 04 BARGUNA 10 04 09 AMTALI 10 04 19 BAMNA 10 04 28 BARGUNA SADAR 10 04 47 BETAGI 10 04 85 PATHARGHATA 10 04 92 TALTALI 10 06 BARISAL 10 06 02 AGAILJHARA 10 06 03 BABUGANJ 10 06 07 BAKERGANJ 10 06 10 BANARI PARA 10 06 32 GAURNADI 10 06 36 HIZLA 10 06 51 BARISAL SADAR (KOTWALI) 10 06 62 MHENDIGANJ 10 06 69 MULADI 10 06 94 WAZIRPUR 10 09 BHOLA 10 09 18 BHOLA SADAR 10 09 21 BURHANUDDIN 10 09 25 CHAR FASSON 10 09 29 DAULAT KHAN 10 09 54 LALMOHAN 10 09 65 MANPURA 10 09 91 TAZUMUDDIN 10 42 JHALOKATI 10 42 40 JHALOKATI SADAR 10 42 43 KANTHALIA 10 42 73 NALCHITY 10 42 84 RAJAPUR 10 78 PATUAKHALI 10 78 38 BAUPHAL 10 78 52 DASHMINA 10 78 55 DUMKI 10 78 57 GALACHIPA 10 78 66 KALAPARA 10 78 76 MIRZAGANJ 10 78 95 PATUAKHALI SADAR 10 78 97 RANGABALI Geo Code list (upto upazila) of Bangladesh As On March, 2013 Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 79 PIROJPUR 10 79 14 BHANDARIA 10 79 47 KAWKHALI 10 79 58 MATHBARIA 10 79 76 NAZIRPUR 10 79 80 PIROJPUR SADAR 10 79 87 NESARABAD (SWARUPKATI) 10 79 90 ZIANAGAR 20 CHITTAGONG DIVISION 20 03 BANDARBAN 20 03 04 ALIKADAM 20 03 14 BANDARBAN SADAR 20 03 51 LAMA 20 03 73 NAIKHONGCHHARI 20 03 89 ROWANGCHHARI 20 03 91 RUMA 20 03 95 THANCHI 20 12 BRAHMANBARIA 20 12 02 AKHAURA 20 12 04 BANCHHARAMPUR 20 12 07 BIJOYNAGAR 20 12 13 BRAHMANBARIA SADAR 20 12 33 ASHUGANJ 20 12 63 KASBA 20 12 85 NABINAGAR 20 12 90 NASIRNAGAR 20 12 94 SARAIL 20 13 CHANDPUR 20 13 22 CHANDPUR SADAR 20 13 45 FARIDGANJ -

Baseline Report of Wash4urbanpoor Project

Baseline Report of WASH4UrbanPoor Project Submitted to Prepared by Avijit Poddar, PhD Faisal M Ahamed, MS Aminur Rahman, MS Submitted by September 2018 Abbreviations BDT Bangladeshi Taka CC City Corporation CCC Chittagong City Corporation DNCC Dhaka North City Corporation DPHE Department of Public Health Engineering DSCC Dhaka South City Corporation HH Household JMP Joint Monitoring Programme KCC Khulna City Corporation MHM Menstrual Hygiene Management NGO Non-government Organization PDC Pavement Dweller Centers ppm Parts Per Million SDG Sustainable Development Goal SDP Sector Development Plan UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund WASA Water Supply & Sewerage Authority WASH Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The present study titled “Baseline study of WASH4UrbanPoor Project” has been initiated by WaterAid Bangladesh for proper understanding of baseline status for their newly launched 5 year program in 6 selected urban areas (Dhaka North City Corporation, Dhaka South City Corporation, Chittagong City Corporation, Khulna City Corporation, Sakhipur Paurashava, and Saidpur Paurashava). WaterAid Bangladesh awarded Human Development Research Centre (HDRC) to conduct the study on this issue. The successful administration of this study would not have been possible without the commitment of all those who were involved in this process. We are grateful to WaterAid Bangladesh for entrusting HDRC to carry out this assignment. We are particularly grateful to Dr. Md. Khairul Islam, Country Director of WaterAid and Mr Imrul Kayes Muniruzzaman for assigning the consultancy to HDRC and reviewing the report and providing feedback. We express our sincere gratitude to Mr Aftab Opel, head of programme for reviewing the report. We thank Ms Mirza Manbira Sultana, Manager M&E for reviewing methodology, checklists and draft report and Mr Babul Bala, Project Manager, for support during survey implementation and reviewing draft report. -

Land Resource Appraisal of Bangladesh for Agricultural

BGD/81/035 Technical Report 3 Volume II LAND RESOURCES APPRAISAL OF BANGLADESH FOR AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT REPORT 3 LAND RESOURCES DATA BASE VOLUME II SOIL, LANDFORM AND HYDROLOGICAL DATA BASE A /UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FAo FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION vJ OF THE UNITED NATIONS BGD/81/035 Technical Report 3 Volume II LAND RESOURCES APPRAISAL OF BANGLADESH FOR AGRICULTURALDEVELOPMENT REPORT 3 LAND RESOURCES DATA BASE VOLUME II SOIL, LANDFORM AND HYDROLOGICAL DATA BASE Report prepared for the Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations acting as executing agency for the United Nations Development Programme based on the work of H. Brammer Agricultural Development Adviser J. Antoine Data Base Management Expert and A.H. Kassam and H.T. van Velthuizen Land Resources and Agricultural Consultants UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 1988 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and AgricultureOrganization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored ina retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopyingor otherwise, without the prior perrnission of (he copyright owner. Applications for such permission,with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressedto the Director, Publications Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viadelle Terme di Caracarla, 00100 Home, Italy. -

List of Madrsha

List of Madrasha Division BARISAL District BARGUNA Thana AMTALI Sl Eiin Name Village/Road Mobile 1 100065 WEST CHILA AMINIA FAZIL MADRASAH WEST CHILA 01716835134 2 100067 MOHAMMADPUR MAHMUDIA DAKHIL MADRASAH MOHAMMADPUR 01710322701 3 100069 AMTALI BONDER HOSAINIA FAZIL MADRASHA AMTALI 01714599363 4 100070 GAZIPUR SENIOR FAZIL (B.A) MADRASHA GAZIPUR 01724940868 5 100071 KUTUBPUR FAZIL MADRASHA KRISHNA NAGAR 01715940924 6 100072 UTTAR KALAMPUR HATEMMIA DAKHIL MADRASA KAMALPUR 01719661315 7 100073 ISLAMPUR HASHANIA DAKHIL MADRASHA ISLAMPUR 01745566345 8 100074 MOHISHKATA NESARIA DAKHIL MADRASA MOHISHKATA 01721375780 9 100075 MADHYA TARIKATA DAKHIL MADRASA MADHYA TARIKATA 01726195017 10 100076 DAKKHIN TAKTA BUNIA RAHMIA DAKHIL MADRASA DAKKHIN TAKTA BUNIA 01718792932 11 100077 GULISHAKHALI DAKHIL MDRASHA GULISHAKHALI 01706231342 12 100078 BALIATALI CHARAKGACHHIA DAKHIL MADRASHA BALIATALI 01711079989 13 100080 UTTAR KATHALIA DAKHIL MADRASAH KATHALIA 01745425702 14 100082 PURBA KEWABUNIA AKBARIA DAKHIL MADRASAH PURBA KEWABUNIA 01736912435 15 100084 TEPURA AHMADIA DAKHIL MADRASA TEPURA 01721431769 16 100085 AMRAGACHIA SHALEHIA DAKHIL AMDRASAH AMRAGACHIA 01724060685 17 100086 RAHMATPUR DAKHIL MADRASAH RAHAMTPUR 01791635674 18 100088 PURBA PATAKATA MEHER ALI SENIOR MADRASHA PATAKATA 01718830888 19 100090 GHOP KHALI AL-AMIN DAKHIL MADRASAH GHOPKHALI 01734040555 20 100091 UTTAR TEPURA ALAHAI DAKHIL MADRASA UTTAR TEPURA 01710020035 21 100094 GHATKHALI AMINUDDIN GIRLS ALIM MADRASHA GHATKHALI 01712982459 22 100095 HARIDRABARIA D.S. DAKHIL MADRASHA HARIDRABARIA -

FSM Convention Report

Workshop Proceedings Faecal Sludge Management Network The Bangladesh Faecal Sludge Management Network (FSMN) is a common and collective platform for the sector actors to generate ideas, share views, influence policy and practice, and raise a collective voice to meet the challenges of sanitation sector. The Network engages WASH stakeholders across civil society, the private sector, academia and the government, including Department of Environment, Department of Agriculture Extension, Sustainable and Renewable Energy Development Authority; relevant taskforces, networks and associations including National Sanitation Secretariat, National Forum for Water and Sanitation, Fertilizers’ Association, etc.; and diverse actors such as corporations, microfinance institutions, etc. Vision Ensuring a safe and sustainable faecal sludge management system in Bangladesh for improved public health and living environment for all by 2030. Mission To act as a knowledge and advocacy platform where FSM is an intermediary solution for influencing policy and changes in practice for access to adequate, equitable and improved sanitation. Objectives The FSMN has the following major objectives: • To work in a collaborative learning approach with all stakeholders to capture evidence, communicate knowledge and facilitate sector capacity building. • To engage and provide strategic guidance to the FSM stakeholders for advancing appropriate technologies and approaches for safe and sustainable management of faecal sludge. Introduction Bangladesh has achieved the remarkable feat of near-elimination of open defecation. However, the country faces formidable challenges in the coming years in moving up the sanitation ladder. The rapid increase in sanitation coverage over the past two decades has relied heavily on on-site sanitation, with little capacity to deal with the volumes of sludge that eventually collect. -

District Budget Experience in Bangladesh: the Case of Tangail Page 2

District Budget Experience in Bangladesh The Case of Tangail Towfiqul Islam Khan Research Fellow, CPD < [email protected] > Mostafa Amir Sabbih Research Associate, CPD < [email protected] > A report prepared under the programme Independent Review of Bangladesh’s Development (IRBD) of the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) Presented at the PRE-BUDGET DIALOGUE 2015 TANGAIL DISTRICT BUDGET AND RELEVANT ISSUES Tangail: 14 March 2015 Contents SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 SECTION 2. SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATE OF TANGAIL DISTRICT.......................................................................................... 5 SECTION 3. REVISITING DISTRICT BUDGET IN TANGAIL: METHOD AND ESTIMATION ................................... 15 SECTION 4. TRACING THE CHANGES: IS THERE ANY? ....................................................................................................... 18 SECTION 5. CONCLUDING REMARKS .......................................................................................................................................... 20 REFERENCES .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 22 ANNEXTURE .......................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Situation Assessment of Public and Private Blood Centres in Bangladesh

Situation Assessment of Public and Private Blood Centres in Bangladesh Situation Assessment of Public and Private Blood Centres in Bangladesh Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Bangladesh. In collaboration with the World Health Organization and the OPEC Fund for International Development (OFID). This report is the product of a ongoing collaboration between the World Health Organization (WHO) and the OPEC Foundation for International Development (OFID); and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Bangladesh. World Health Organization 2012 This health information product is intended for a restricted audience only. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this health information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. The World Health Organization does not warrant that the information contained in this health information product is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result of its use. 1 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary ii 1. -

FSM6 Conference “Towards a Sustainable Business Model in Sakhipur Municipality, Bangladesh”

FSM6 Conference “Towards A Sustainable Business Model in Sakhipur Municipality, Bangladesh” Fariha Nehrin Mili WASH Coordinator BASA Foundation FSM Scenario in Bangladesh . People practicing open defecation in Bangladesh was reported at 0 % in 2017, according to the World Bank; . 86% households had access to an improved latrine of which 49% were pit latrines, 24% septic tanks and 13% piped to a sewer system; . About 2% households had no latrine access and those were decreasing from poorest quintile to wealthiest quintile; . Currently, 26% of the total population and about 29% of urban population depend on shared facilities. However, increasing use of on-site sanitation facilities has generated a large demand for fecal sludge management (FSM) to keep the toilets operational. In the absence of effective FSM services, the huge quantities of fecal sludge generated in septic tanks and pits are inaptly managed. Disposal of fecal sludge in low-lying areas and in lakes and canals within urban areas is common, leading to serious environmental degradation. Overview on Sakhipur Municipality Sakhipur, the second biggest upazila of Tangail District in respect of area, came into existence in 1976 as a thana and was upgraded to upazila in 1983 having one municipality. Location North-central part of Bangladesh Total Area 19 km2 Total Population 30,028 (approx.)- with a density of around 2,611 people / km2 Waste Input Type Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) , Faecal Sludge Faecal Sludge and MSW collection and transportation service Value Offer Co-compost (faecal sludge and organic waste treatment and reuse) as soil conditioner BASA Foundation – towards achieving sustainability WASH4 Urban Poor Project: Project started in April 2015 and expected to run until 2023. -

জলা পিরসং ান 3122 Uv½vbj District Statistics 2011 Tangail

জলা পিরসংান 3122 Uv½vBj District Statistics 2011 Tangail December 2013 BANGLADESH BUREAU OF STATISTICS (BBS) STATISTICS AND INFORMATICS DIVISION (SID) MINISTRY OF PLANNING GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH District Statistics 2011 Published in December, 2013 Published by : Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Printed at : Reproduction, Documentation and Publication (RDP) Section, FA & MIS, BBS Cover Design: Chitta Ranjon Ghosh, RDP, BBS ISBN: For further information, please contact: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Statistics and Informatics Division (SID) Ministry of Planning Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Parishankhan Bhaban E-27/A, Agargaon, Dhaka-1207. www.bbs.gov.bd COMPLIMENTARY This book or any portion thereof cannot be copied, microfilmed or reproduced for any commercial purpose. Data therein can, however, be used and published with acknowledgement of the sources. ii Foreword I am delighted to learn that Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) has successfully completed the ‘District Statistics 2011’ under Medium-Term Budget Framework (MTBF). The initiative of publishing ‘District Statistics 2011’ has been undertaken considering the importance of district and upazila level data in the process of determining policy, strategy and decision-making. The basic aim of the activity is to publish the various priority statistical information and data relating to all the districts of Bangladesh. The data are collected from various upazilas belonging to a particular district. The Government has been preparing and implementing various short, medium and long term plans and programs of development in all sectors of the country in order to realize the goals of Vision 2021. For any pragmatic approach in formulating and evaluating development plans and programs reliable statistics are indispensible.