Evaluation of Netherlands-Funded Ngos in Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangladesh, Year 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED)

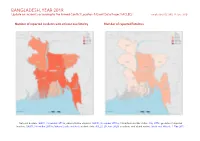

BANGLADESH, YEAR 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 29 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; China/India border status: CIA, 2006; geodata of disputed borders: GADM, November 2015b; Natural Earth, undated; incident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 BANGLADESH, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 29 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Protests 930 1 1 Conflict incidents by category 2 Riots 405 107 122 Development of conflict incidents from 2010 to 2019 2 Violence against civilians 257 184 195 Battles 99 43 63 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 15 0 0 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 7 2 2 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 1713 337 383 Disclaimer 6 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2010 to 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 BANGLADESH, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 29 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. -

Division Name District Name Upazila Name 1 Dhaka 1 Dhaka 1 Dhamrai 2 Dohar 3 Keraniganj 4 Nawabganj 5 Savar

Division name District Name Upazila Name 1 Dhaka 1 Dhamrai 1 Dhaka 2 Dohar 3 Keraniganj 4 Nawabganj 5 Savar 2 Faridpur 1 Alfadanga 2 Bhanga 3 Boalmari 4 Char Bhadrasan 5 Faridpur Sadar 6 Madhukhali 7 Nagarkanda 8 Sadarpur 9 Saltha 3 Gazipur 1 Gazipur Sadar 2 Kaliakoir 3 Kaliganj 4 Kapasia 5 Sreepur 4 Gopalganj 1 Gopalganj Sadar 2 Kasiani 3 Kotalipara 4 Maksudpur 5 Tungipara 5 Jamalpur 1 Bakshiganj 2 Dewanganj 3 Islampur 4 Jamalpur Sadar 5 Madarganj 6 Melandah 7 Sharishabari 6 Kishoreganj 1 Austogram 2 Bajitpur 3 Bhairab 4 Hosainpur 5 Itna 6 Karimganj 7 Katiadi 8 Kishoreganj Sadar 9 Kuliarchar 10 Mithamain 11 Nikli 12 Pakundia 13 Tarail 7 Madaripur 1 Kalkini 2 Madaripur Sadar 3 Rajoir 4 Shibchar 8 Manikganj 1 Daulatpur 2 Ghior 3 Harirampur 4 Manikganj Sadar 5 Saturia 6 Shibalaya 7 Singair 9 Munshiganj 1 Gazaria 2 Lauhajang 3 Munshiganj Sadar 4 Serajdikhan 5 Sreenagar 6 Tangibari 10 Mymensingh 1 Bhaluka 2 Dhubaura 3 Fulbaria 4 Fulpur 5 Goffargaon 6 Gouripur 7 Haluaghat 8 Iswarganj 9 Mymensingh Sadar 10 Muktagacha 11 Nandail 12 Trishal 11 Narayanganj 1 Araihazar 2 Bandar 3 Narayanganj Sadar 4 Rupganj 5 Sonargaon 12 Norshingdi 1 Belabo 2 Monohardi 3 Norshingdi Sadar 4 Palash 5 Raipura 6 Shibpur 13 Netrokona 1 Atpara 2 Barhatta 3 Durgapur 4 Kalmakanda 5 Kendua 6 Khaliajuri 7 Madan 8 Mohanganj 9 Netrokona Sadar 10 Purbadhala 14 Rajbari 1 Baliakandi 2 Goalunda 3 Pangsha 4 Rajbari Sadar 5 Kalukhale 15 Shariatpur 1 Bhedarganj 2 Damudiya 3 Gosairhat 4 Zajira 5 Naria 6 Shariatpur Sadar 16 Sherpur 1 Jhenaigati 2 Nakla 3 Nalitabari 4 Sherpur Sadar -

Planning and Prioritisation of Rural Roads in Bangladesh Final Report- Volume 2

Planning and Prioritisation of Rural Roads in Bangladesh Final Report- Volume 2 Department of Urban and Regional Planning (DURP) Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET) February 2018 (Revised) Planning and Prioritisation of Rural Roads in Bangladesh The analyses presented and views expressed in this report are those of the authors and they do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of Bangladesh, Local Government Engineering Department, Research for Community Access Partnership (ReCAP) or Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET). Cover Photo: Mr. Md. Mashrur Rahman using LGED’s GIS Database Quality assurance and review table Version Author(s) Reviewer(s) Date Department URP, BUET Les Sampson and October 13, 2017 1 Maysam Abedin, ReCAP Department URP, BUET Abul Monzur Md. Sadeque and October 19, 2017 Md. Sohel Rana, LGED Department URP, BUET Les Sampson and January 10, 2018 2 Maysam Abedin, ReCAP Department URP, BUET Abul Monzur Md. Sadeque and January 27, 2018 Md. Sohel Rana, LGED ReCAP Project Management Unit Cardno Emerging Market (UK) Ltd Oxford House, Oxford Road Thame OX9 2AH United Kingdom Page 2 Planning and Prioritisation of Rural Roads in Bangladesh Key words Bangladesh, Rural Road, Rural Road Prioritisation, Rural Road Network Planning, Core Road Network, Multi Criteria Analysis, Cost Benefit Analysis, Local Government Engineering Department. RESEACH FOR COMMUNITY ACCESS PARTNERSHIP (ReCAP) Safe and sustainable transport for rural communities ReCAP is a research programme, funded by UK Aid, with the aim of promoting safe and sustainable transport for rural communities in Africa and Asia. ReCAP comprises the Africa Community Access Partnership (AfCAP) and the Asia Community Access Partnership (AsCAP). -

Sakhipur, Bangladesh

Small town sanitation learning series Sakhipur, Bangladesh July 2020 View of the co-composting plant and its drying beds in the foreground WaterAid/ Al-Emran WaterAid/ Key messages 1. The small town of Sakhipur is on track to achieve town-wide safely managed sanitation, the result of technical excellence (including its co-composting plant), political drive, a clear vision, and support by WaterAid Bangladesh. 2. Local partnerships are vital to close the sanitation service chain such as the Agricultural Extension Department. 3. The sanitation vision includes both considering sanitation as a service and using the principles of circular economy. 4. Fostering municipal leadership and ownership is a slow but critical process, which can be the focus of national level advocacy for future replication. 1 / Small town sanitation learning series Sakhipur, Bangladesh July 2020 1. Introduction WaterAid Bangladesh (WAB) and the Bangladesh Association for Social Advancement (BASA) have supported Sakhipur Municipality both technically and financially to establish a co-composting plant in 2015. The plant treats both faecal sludge and organic solid waste to produce compost. The technical achievement has been well recognised and documented. This brief is mainly focusing at non-technical aspects, especially how this plant (and work around it) is paving the way for full safely-managed sanitation in the town, what has led to this success, and how it could be replicated. 2. Context Bangladesh has impressively reached almost zero open defecation and is now facing the “second generation” challenge of faecal sludge management (FSM) – with 32% “safely managed sanitation” in rural areas, and no urban estimate. -

Download File

Cover and section photo credits Cover Photo: “Untitled” by Nurus Salam is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 (Shangu River, Bangladesh). https://www.flickr.com/photos/nurus_salam_aupi/5636388590 Country Overview Section Photo: “village boy rowing a boat” by Nasir Khan is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nasir-khan/7905217802 Disaster Overview Section Photo: Bangladesh firefighters train on collaborative search and rescue operations with the Bangladesh Armed Forces Division at the 2013 Pacific Resilience Disaster Response Exercise & Exchange (DREE) in Dhaka, Bangladesh. https://www.flickr.com/photos/oregonmildep/11856561605 Organizational Structure for Disaster Management Section Photo: “IMG_1313” Oregon National Guard. State Partnership Program. Photo by CW3 Devin Wickenhagen is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/oregonmildep/14573679193 Infrastructure Section Photo: “River scene in Bangladesh, 2008 Photo: AusAID” Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/dfataustralianaid/10717349593/ Health Section Photo: “Arsenic safe village-woman at handpump” by REACH: Improving water security for the poor is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/reachwater/18269723728 Women, Peace, and Security Section Photo: “Taroni’s wife, Baby Shikari” USAID Bangladesh photo by Morgana Wingard. https://www.flickr.com/photos/usaid_bangladesh/27833327015/ Conclusion Section Photo: “A fisherman and the crow” by Adnan Islam is licensed under CC BY 2.0. Dhaka, Bangladesh. https://www.flickr.com/photos/adnanbangladesh/543688968 Appendices Section Photo: “Water Works Road” in Dhaka, Bangladesh by David Stanley is licensed under CC BY 2.0. -

BRTC Bus Routes and Bus Numbers of Its Own Managed Depot Dhaka Total Sl Routs Routs Number Depot Name Routs Routs No

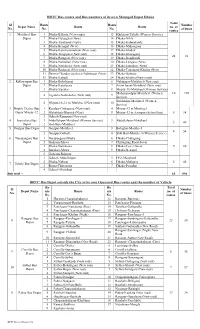

BRTC Bus routes and Bus numbers of its own Managed Depot Dhaka Total Sl Routs Routs Number Depot Name Routs Routs no. of No. No. No. of buses routes 1. Motijheel Bus 1 Dhaka-B.Baria (New routs) 13 Khilgoan-Taltola (Women Service) Depot 2 Dhaka-Haluaghat (New) 14 Dhaka-Nikli 3 Dhaka-Tarakandi (New) 15 Dhaka-Kalmakanda 4 Dhaka-Benapul (New) 16 Dhaka-Muhongonj 5 Dhaka-Kutichowmuhoni (New rout) 17 Dhaka-Modon 6 Dhaka-Tongipara (New rout) 18 Dhaka-Ishoregonj 24 82 7 Dhaka-Ramgonj (New rout) 19 Dhaka-Daudkandi 8 Dhaka-Nalitabari (New rout) 20 Dhaka-Lengura (New) 9 Dhaka-Netrakona (New rout) 21 Dhaka-Jamalpur (New) 10 Dhaka-Ramgonj (New rout) 22 Dhaka-Tongipara-Khulna (New) 11 Demra-Chandra via Savar Nabinagar (New) 23 Dhaka-Bajitpur 12 Dhaka-Katiadi 24 Dhaka-Khulna (New routs) 2. Kallayanpur Bus 1 Dhaka-Bokshigonj 6 Nabinagar-Motijheel (New rout) Depot 2 Dhaka-Kutalipara 7 Zirani bazar-Motijheel (New rout) 3 Dhaka-Sapahar 8 Mirpur-10-Motijheel (Women Service) Mohammadpur-Motijheel (Women 10 198 4 Zigatola-Notunbazar (New rout) 9 Service) Siriakhana-Motijheel (Women 5 Mirpur-10-2-1 to Motijheel (New rout) 10 Service) 3. Double Decker Bus 1 Kendua-Chittagong (New rout) 4 Mirpur-12 to Motijheel Depot Mirpur-12 2 Mohakhali-Bhairob (New) 5 Mirpur-12 to Azimpur (School bus) 5 38 3 Gabtoli-Rampura (New rout) 4. Joarsahara Bus 1 Abdullahpur-Motijheel (Women Service) 3 Abdullahpur-Motijheel 5 49 Depot 2 Shib Bari-Motijheel 5. Gazipur Bus Depot 1 Gazipur-Motijheel 3 Balughat-Motijheel 4 54 2 Gazipur-Gabtoli 4 Shib Bari-Motijheel (Women Service) 6. -

Farmers' Organizations in Bangladesh: a Mapping and Capacity

Farmers’ Organizations in Bangladesh: Investment Centre Division A Mapping and Capacity Assessment Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Viale delle Terme di Caracalla – 00153 Rome, Italy. Bangladesh Integrated Agricultural Productivity Project Technical Assistance Component FAO Representation in Bangladesh House # 37, Road # 8, Dhanmondi Residential Area Dhaka- 1205. iappta.fao.org I3593E/1/01.14 Farmers’ Organizations in Bangladesh: A Mapping and Capacity Assessment Bangladesh Integrated Agricultural Productivity Project Technical Assistance Component Food and agriculture organization oF the united nations rome 2014 Photo credits: cover: © CIMMYt / s. Mojumder. inside: pg. 1: © FAO/Munir uz zaman; pg. 4: © FAO / i. nabi Khan; pg. 6: © FAO / F. Williamson-noble; pg. 8: © FAO / i. nabi Khan; pg. 18: © FAO / i. alam; pg. 38: © FAO / g. napolitano; pg. 41: © FAO / i. nabi Khan; pg. 44: © FAO / g. napolitano; pg. 47: © J.F. lagman; pg. 50: © WorldFish; pg. 52: © FAO / i. nabi Khan. Map credit: the map on pg. xiii has been reproduced with courtesy of the university of texas libraries, the university of texas at austin. the designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and agriculture organization of the united nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. the mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

List of Pourashava (Division and Category Wise)

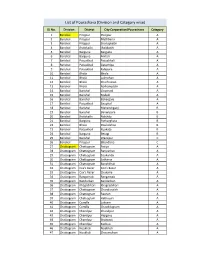

List of Pourashava (Division and Category wise) SL No. Division District City Corporation/Pourashava Category 1 Barishal Pirojpur Pirojpur A 2 Barishal Pirojpur Mathbaria A 3 Barishal Pirojpur Shorupkathi A 4 Barishal Jhalokathi Jhalakathi A 5 Barishal Barguna Barguna A 6 Barishal Barguna Amtali A 7 Barishal Patuakhali Patuakhali A 8 Barishal Patuakhali Galachipa A 9 Barishal Patuakhali Kalapara A 10 Barishal Bhola Bhola A 11 Barishal Bhola Lalmohan A 12 Barishal Bhola Charfession A 13 Barishal Bhola Borhanuddin A 14 Barishal Barishal Gournadi A 15 Barishal Barishal Muladi A 16 Barishal Barishal Bakerganj A 17 Barishal Patuakhali Bauphal A 18 Barishal Barishal Mehendiganj B 19 Barishal Barishal Banaripara B 20 Barishal Jhalokathi Nalchity B 21 Barishal Barguna Patharghata B 22 Barishal Bhola Doulatkhan B 23 Barishal Patuakhali Kuakata B 24 Barishal Barguna Betagi B 25 Barishal Barishal Wazirpur C 26 Barishal Pirojpur Bhandaria C 27 Chattogram Chattogram Patiya A 28 Chattogram Chattogram Bariyarhat A 29 Chattogram Chattogram Sitakunda A 30 Chattogram Chattogram Satkania A 31 Chattogram Chattogram Banshkhali A 32 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Cox’s Bazar A 33 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Chakaria A 34 Chattogram Rangamati Rangamati A 35 Chattogram Bandarban Bandarban A 36 Chattogram Khagrchhari Khagrachhari A 37 Chattogram Chattogram Chandanaish A 38 Chattogram Chattogram Raozan A 39 Chattogram Chattogram Hathazari A 40 Chattogram Cumilla Laksam A 41 Chattogram Cumilla Chauddagram A 42 Chattogram Chandpur Chandpur A 43 Chattogram Chandpur Hajiganj A -

Curriculum Vitae of Mohammad Shameem Al Mamun

CURRICULUM VITAE OF MOHAMMAD SHAMEEM AL MAMUN Contact Address: Senior Scientific Officer & Head, Entomology Division Bangladesh Tea Research Institute Srimangal-3210, Moulvibazar, Bangladesh Phone: +880862671225 (Office) Fax: +880862671930 Cell: +8801712119843 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://shameembtri.webs.com http://bau.academia.edu/msamamun http://facebook.com/shameembtri http://publicationslist.org/shameembtri http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6322-0348 http://livedna.org/880.5244 http://btri.gov.bd Career Objective To develop my career as a good scientist as well as a successful researcher from where I will have the scope to utilize my potentiality & skills to do something innovative and I will be able to enhance my knowledge. Field of Research Bio-ecology of pests, Distributional pattern & seasonal abundance of pests, Crop loss assessment, Bioassay and resistance of pests, Integrated pest management (IPM) in tea, Bio- pesticides & Bio-control as IPM component, Screening of tea clones for pest susceptibility, Screening and standardizing of pesticides for tea and Pesticide residue in tea. Special Qualification Integrated Pest Management, Bio-pesticides and Pesticide residue in tea Key Qualifications Planning, formulating, guiding and conducting entomological researches for tea. Pesticide residue detection and analysis of made tea is another specialized field of work. Conducting laboratory and field trial related to pest management in tea. Analyzing nematodes from the nursery soils of the tea estates. Rendering all sorts of advisory services to the tea estates on the problems arising out of pests of tea. Resource person of Management Training Centre, Project Development Unit, Bangladesh Tea Board. Conducting workshop on tea pest management for planters, managers & staffs of the tea estates. -

Cropping Pattern, Intensity and Diversity in Dhaka Region

Bangladesh Rice J. 21 (2) : 123-141, 2017 Cropping Pattern, Intensity and Diversity in Dhaka Region N Parvin1*, A Khatun1, M K Quais1 and M Nasim1 ABSTRACT Sustainable crop production in Bangladesh through improvement of cropping intensity and crop diversity in rice based cropping system is regarded as increasingly important in national issues. Planning of agricultural development largely depends on the authentic, reliable and comprehensive statistics of the existing cropping patterns, cropping intensity and crop diversity of a particular area, which will provide guideline to our policy makers, researchers, extensionists and development workers. The study was conducted over all 46 upazilas of Dhaka agricultural region in 2015 using pretested semi-structured questionnaire with a view to document the existing cropping patterns, cropping intensity and crop diversity in the region. From the present study, it was observed that about 48.27% net cropped area (NCA) is covered by exclusive rice cropping systems whereas deep water rice occupied about 16.57% of the regional NCA. The most dominant cropping pattern Boro−Fallow−T. Aman alone occupied about 22.59% of net cropped area (NCA) with its distribution over 32 upazilas out of 46. The second largest area was covered by single Boro cropping pattern, which was spread over 44 upazilas. Total number of cropping patterns was observed 164. The highest number of cropping pattern was identified 35 in Tangail sadar and Dhamrai upazila of Dhaka district and the lowest was seven in Bandar of Narayanganj and Palash of Narsingdi district. The lowest crop diversity index (CDI) was reported as 0.70 in Dhamrai followed by 0.72 in Monohardi of Narsingdi. -

Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 10 04 10 04

Geo Code list (upto upazila) of Bangladesh As On March, 2013 Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 BARISAL DIVISION 10 04 BARGUNA 10 04 09 AMTALI 10 04 19 BAMNA 10 04 28 BARGUNA SADAR 10 04 47 BETAGI 10 04 85 PATHARGHATA 10 04 92 TALTALI 10 06 BARISAL 10 06 02 AGAILJHARA 10 06 03 BABUGANJ 10 06 07 BAKERGANJ 10 06 10 BANARI PARA 10 06 32 GAURNADI 10 06 36 HIZLA 10 06 51 BARISAL SADAR (KOTWALI) 10 06 62 MHENDIGANJ 10 06 69 MULADI 10 06 94 WAZIRPUR 10 09 BHOLA 10 09 18 BHOLA SADAR 10 09 21 BURHANUDDIN 10 09 25 CHAR FASSON 10 09 29 DAULAT KHAN 10 09 54 LALMOHAN 10 09 65 MANPURA 10 09 91 TAZUMUDDIN 10 42 JHALOKATI 10 42 40 JHALOKATI SADAR 10 42 43 KANTHALIA 10 42 73 NALCHITY 10 42 84 RAJAPUR 10 78 PATUAKHALI 10 78 38 BAUPHAL 10 78 52 DASHMINA 10 78 55 DUMKI 10 78 57 GALACHIPA 10 78 66 KALAPARA 10 78 76 MIRZAGANJ 10 78 95 PATUAKHALI SADAR 10 78 97 RANGABALI Geo Code list (upto upazila) of Bangladesh As On March, 2013 Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 79 PIROJPUR 10 79 14 BHANDARIA 10 79 47 KAWKHALI 10 79 58 MATHBARIA 10 79 76 NAZIRPUR 10 79 80 PIROJPUR SADAR 10 79 87 NESARABAD (SWARUPKATI) 10 79 90 ZIANAGAR 20 CHITTAGONG DIVISION 20 03 BANDARBAN 20 03 04 ALIKADAM 20 03 14 BANDARBAN SADAR 20 03 51 LAMA 20 03 73 NAIKHONGCHHARI 20 03 89 ROWANGCHHARI 20 03 91 RUMA 20 03 95 THANCHI 20 12 BRAHMANBARIA 20 12 02 AKHAURA 20 12 04 BANCHHARAMPUR 20 12 07 BIJOYNAGAR 20 12 13 BRAHMANBARIA SADAR 20 12 33 ASHUGANJ 20 12 63 KASBA 20 12 85 NABINAGAR 20 12 90 NASIRNAGAR 20 12 94 SARAIL 20 13 CHANDPUR 20 13 22 CHANDPUR SADAR 20 13 45 FARIDGANJ -

Bangladesh Country Report 2018

. Photo: Children near an unsecured former smelting site in the Ashulia area outside of Dhaka Toxic Sites Identification Program in Bangladesh Award: DCI-ENV/2015/371157 Prepared by: Andrew McCartor Prepared for: UNIDO Date: November 2018 Pure Earth 475 Riverside Drive, Suite 860 New York, NY, USA +1 212 647 8330 www.pureearth.org List of Acronyms ...................................................................................................................... 1 List of Annexes ......................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction............................................................................................................................... 2 Background............................................................................................................................... 2 Toxic Sites Identification Program (TSIP) ............................................................................. 3 TSIP Training ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Implementation Strategy and Coordination with Government .......................................... 4 Program Implementation Activities ..................................................................................................... 4 Analysis of Environmental