Personal Accounts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World Bank Implementation Status & Results

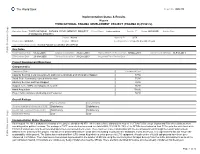

The World Bank Report No: ISR4370 Implementation Status & Results Nigeria THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (FADAMA III) (P096572) Operation Name: THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 7 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: (FADAMA III) (P096572) Country: Nigeria Approval FY: 2009 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): National Fadama Coordination Office(NFCO) Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 01-Jul-2008 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date 07-Nov-2011 Last Archived ISR Date 11-Feb-2011 Effectiveness Date 23-Mar-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Capacity Building, Local Government, and Communications and Information Support 87.50 Small-Scale Community-owned Infrastructure 75.00 Advisory Services and Input Support 39.50 Support to the ADPs and Adaptive Research 36.50 Asset Acquisition 150.00 Project Administration, Monitoring and Evaluation 58.80 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Low Low Implementation Status Overview As at August 19, 2011, disbursement status of the project stands at 46.87%. All the states have disbursed to most of the FCAs/FUGs except Jigawa and Edo where disbursement was delayed for political reasons. The savings in FUEF accounts has increased to a total ofN66,133,814.76. 75% of the SFCOs have federated their FCAs up to the state level while FCAs in 8 states have only been federated up to the Local Government levels. -

Surviving Works: Context in Verre Arts Part One, Chapter One: the Verre

Surviving Works: context in Verre arts Part One, Chapter One: The Verre Tim Chappel, Richard Fardon and Klaus Piepel Special Issue Vestiges: Traces of Record Vol 7 (1) (2021) ISSN: 2058-1963 http://www.vestiges-journal.info Preface and Acknowledgements (HTML | PDF) PART ONE CONTEXT Chapter 1 The Verre (HTML | PDF) Chapter 2 Documenting the early colonial assemblage – 1900s to 1910s (HTML | PDF) Chapter 3 Documenting the early post-colonial assemblage – 1960s to 1970s (HTML | PDF) Interleaf ‘Brass Work of Adamawa’: a display cabinet in the Jos Museum – 1967 (HTML | PDF) PART TWO ARTS Chapter 4 Brass skeuomorphs: thinking about originals and copies (HTML | PDF) Chapter 5 Towards a catalogue raisonnée 5.1 Percussion (HTML | PDF) 5.2 Personal Ornaments (HTML | PDF) 5.3 Initiation helmets and crooks (HTML | PDF) 5.4 Hoes and daggers (HTML | PDF) 5.5 Prestige skeuomorphs (HTML | PDF) 5.6 Anthropomorphic figures (HTML | PDF) Chapter 6 Conclusion: late works ̶ Verre brasscasting in context (HTML | PDF) APPENDICES Appendix 1 The Verre collection in the Jos and Lagos Museums in Nigeria (HTML | PDF) Appendix 2 Chappel’s Verre vendors (HTML | PDF) Appendix 3 A glossary of Verre terms for objects, their uses and descriptions (HTML | PDF) Appendix 4 Leo Frobenius’s unpublished Verre ethnological notes and part inventory (HTML | PDF) Bibliography (HTML | PDF) This work is copyright to the authors released under a Creative Commons attribution license. PART ONE CONTEXT Chapter 1 The Verre Predominantly living in the Benue Valley of eastern middle-belt Nigeria, the Verre are one of that populous country’s numerous micro-minorities. -

Nigeria Update to the IMB Nigeria

Progress in Polio Eradication Initiative in Nigeria: Challenges and Mitigation Strategies 16th Independent Monitoring Board Meeting 1 November 2017 London 0 Outline 1. Epidemiology 2. Challenges and Mitigation strategies SIAs Surveillance Routine Immunization 3. Summary and way forward 1 Epidemiology 2 Polio Viruses in Nigeria, 2015-2017 Past 24 months Past 12 months 3 Nigeria has gone 13 months without Wild Polio Virus and 11 months without cVDPV2 13 months without WPV 11 months – cVDPV2 4 Challenges and Mitigation strategies 5 SIAs 6 Before the onset of the Wild Polio Virus Outbreak in July 2016, there were several unreached settlements in Borno Borno Accessibility Status by Ward, March 2016 # of Wards in % Partially LGAs % Fully Accessible % Inaccessible LGA Accessible Abadam 10 0% 0% 100% Askira-Uba 13 100% 0% 0% Bama 14 14% 0% 86% Bayo 10 100% 0% 0% Biu 11 91% 9% 0% Chibok 11 100% 0% 0% Damboa 10 20% 0% 80% Dikwa 10 10% 0% 90% Gubio 10 50% 10% 40% Guzamala 10 0% 0% 100% Gwoza 13 8% 8% 85% Hawul 12 83% 17% 0% Jere 12 50% 50% 0% Kaga 15 0% 7% 93% Kala-Balge 10 0% 0% 100% Konduga 11 0% 64% 36% Kukawa 10 20% 0% 80% Kwaya Kusar 10 100% 0% 0% Mafa 12 8% 0% 92% Magumeri 13 100% 0% 0% Maiduguri 15 100% 0% 0% Marte 13 0% 0% 100% Mobbar 10 0% 0% 100% Monguno 12 8% 0% 92% Ngala 11 0% 0% 100% Nganzai 12 17% 0% 83% Shani 11 100% 0% 0% State 311 41% 6% 53% 7 Source: Borno EOC Data team analysis Four Strategies were deployed to expand polio vaccination reach and increase population immunity in Borno state SIAs RES2 RIC4 Special interventions 12 -

First State Integrity Meeting in Katsina

First State Integrity Meeting in Katsina Edited and co-auhtored by; Petter Langseth and Oliver Stolpe UNODC’s Global Programme against Corruption Katsina, 18-19 June 2003 Disclaimer The views expressed herein are those of the authors and editors and not necessarily those of the United Nations 2 TABLE OF CONTENT I. FOREWORD............................................................................................................... 4 II. OVERVIEW................................................................................................................. 5 A. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 5 B. Origins of the initiative.............................................................................................. 5 C. The way forward in Nigeria ....................................................................................... 6 D. The First Judicial Integrity Meeting.......................................................................... 6 E. Follow-up action identified in the course of the Workshop....................................... 7 III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY......................................................................................... 10 A. The State Integrity Meeting...................................................................................... 10 B. Conclusions and Recommendations ....................................................................... 10 C. Katsina State. Summary Anti Corruption Action Plan ........................................... -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT FEBRUARY 13, 2019 S/N Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 4 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 5 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 6 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 7 Above Only Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Benson Idahosa University Campus, Ugbor GRA, Benin EDO Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank 8 Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi BAUCHI 9 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 10 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 11 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 12 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 13 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 14 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. Area, Nasarawa State NASSARAWA 15 Adazi-Enu Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Nkwor Market Square, Adazi- Enu, Anaocha Local Govt, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 16 Adazi-Nnukwu Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Near Eke Market, Adazi Nnukwu, Adazi, Anambra State ANAMBRA 17 Addosser Microfinance Bank Limited State 32, Lewis Street, Lagos Island, Lagos State LAGOS 18 Adeyemi College Staff Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Adeyemi College of Education Staff Ni 1, CMS Ltd Secretariat, Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo ONDO 19 Afekhafe Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit No. -

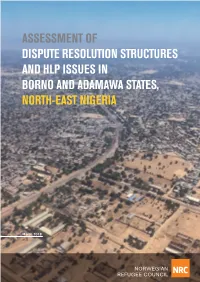

Assessment of Dispute Resolution Structures and Hlp Issues in Borno and Adamawa States, North-East Nigeria

ASSESSMENT OF DISPUTE RESOLUTION STRUCTURES AND HLP ISSUES IN BORNO AND ADAMAWA STATES, NORTH-EAST NIGERIA March 2018 1 The Norwegian Refugee Council is an independent humanitarian organisation helping people forced to flee. Prinsensgate 2, 0152 Oslo, Norway Authors Majida Rasul and Simon Robins for the Norwegian Refugee Council, September 2017 Graphic design Vidar Glette and Sara Sundin, Ramboll Cover photo Credit NRC. Aerial view of the city of Maiduguri. Published March 2018. Queries should be directed to [email protected] The production team expresses their gratitude to the NRC staff who contributed to this report. This project was funded with UK aid from the UK government. The contents of the document are the sole responsibility of the Norwegian Refugee Council and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or policies of the UK Government. AN ASSESSMENT OF DISPUTE RESOLUTION STRUCTURES AND HLP ISSUES IN BORNO AND ADAMAWA STATES 2 Contents Executive summary ..........................................................................................5 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................................................8 Recommendations ......................................................................................................................................................9 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................10 1.1 Purpose of -

Nigeria – Complex Emergency JUNE 7, 2021

Fact Sheet #3 Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 Nigeria – Complex Emergency JUNE 7, 2021 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 206 8.7 2.9 308,000 12.8 MILLION MILLION MILLION MILLION Estimated Estimated Number of Estimated Estimated Projected Acutely Population People in Need in Number of IDPs Number of Food-Insecure w of Nigeria Northeast Nigeria in Nigeria Nigerian Refugees Population for 2021 in West Africa Lean Season UN – December 2020 UN – February 2021 UNHCR – February 2021 UNHCR – April 2021 CH – March 2021 Major OAG attacks on population centers in northeastern Nigeria—including Borno State’s Damasak town and Yobe State’s Geidam town—have displaced hundreds of thousands of people since late March. Intercommunal violence and OCG activity continue to drive displacement and exacerbate needs in northwest Nigeria. Approximately 12.8 million people will require emergency food assistance during the June-to-August lean season, representing a significant deterioration of food security in Nigeria compared with 2020. 1 TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA $230,973,400 For the Nigeria Response in FY 2021 State/PRM2 $13,500,000 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 7 Total $244,473,400 1 USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) 2 U.S. Department of State Bureau for Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM) 1 KEY DEVELOPMENTS Violence Drives Displacement and Constrains Access in the Northeast Organized armed group (OAG) attacks in Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe states have displaced more than 200,000 people since March and continue to exacerbate humanitarian needs and limit relief efforts, according to the UN. -

Empowering Women in West African Markets Case Studies from Kano, Katsina (Nigeria) and Maradi (Niger)

Fighting Hunger Worldwide Empowering Women in West African Markets Case Studies from Kano, Katsina (Nigeria) and Maradi (Niger) VAM Gender and Markets Study #7 2017 1 The Zero Hunger Challenge emphasizes the importance of strengthening economic empowerment in support of the Sustainable Development Goal 2 to double small-scale producer incomes and productivity. The increasing focus on resilient markets can bring important contributions to sustainable food systems and build resilience. Participation in market systems is not only a means for people to secure their livelihood, but it also enables them to exercise agency, maintain dignity, build social capital and increase self-worth. Food security analysis must take into account questions of gender-based violence and discrimination in order to deliver well-tailored assistance to those most in need. WFP’s Nutrition Policy (2017-2021) reconfirms that gender equality and women’s empowerment are essential to achieve good nutrition and sustainable and resilient livelihoods, which are based on human rights and justice. This is why gender-sensitive analysis in nutrition programmes is a crucial contribution to achieving the SDGs. The VAM Gender & Markets Initiative of the WFP Regional Bureau for West and Central Africa seeks to strengthen WFP and partners’ commitment, accountability and capacities for gender-sensitive food security and nutrition analysis in order to design market-based interventions that empower women and vulnerable populations. The series of regional VAM Gender and Markets Studies is an effort to build the evidence base and establish a link to SDG 5 which seeks to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. -

Access Bank Branches Nationwide

LIST OF ACCESS BANK BRANCHES NATIONWIDE ABUJA Town Address Ademola Adetokunbo Plot 833, Ademola Adetokunbo Crescent, Wuse 2, Abuja. Aminu Kano Plot 1195, Aminu Kano Cresent, Wuse II, Abuja. Asokoro 48, Yakubu Gowon Crescent, Asokoro, Abuja. Garki Plot 1231, Cadastral Zone A03, Garki II District, Abuja. Kubwa Plot 59, Gado Nasko Road, Kubwa, Abuja. National Assembly National Assembly White House Basement, Abuja. Wuse Market 36, Doula Street, Zone 5, Wuse Market. Herbert Macaulay Plot 247, Herbert Macaulay Way Total House Building, Opposite NNPC Tower, Central Business District Abuja. ABIA STATE Town Address Aba 69, Azikiwe Road, Abia. Umuahia 6, Trading/Residential Area (Library Avenue). ADAMAWA STATE Town Address Yola 13/15, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola. AKWA IBOM STATE Town Address Uyo 21/23 Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom. ANAMBRA STATE Town Address Awka 1, Ajekwe Close, Off Enugu-Onitsha Express way, Awka. Nnewi Block 015, Zone 1, Edo-Ezemewi Road, Nnewi. Onitsha 6, New Market Road , Onitsha. BAUCHI STATE Town Address Bauchi 24, Murtala Mohammed Way, Bauchi. BAYELSA STATE Town Address Yenagoa Plot 3, Onopa Commercial Layout, Onopa, Yenagoa. BENUE STATE Town Address Makurdi 5, Ogiri Oko Road, GRA, Makurdi BORNO STATE Town Address Maiduguri Sir Kashim Ibrahim Way, Maiduguri. CROSS RIVER STATE Town Address Calabar 45, Muritala Mohammed Way, Calabar. Access Bank Cash Center Unicem Mfamosing, Calabar DELTA STATE Town Address Asaba 304, Nnebisi, Road, Asaba. Warri 57, Effurun/Sapele Road, Warri. EBONYI STATE Town Address Abakaliki 44, Ogoja Road, Abakaliki. EDO STATE Town Address Benin 45, Akpakpava Street, Benin City, Benin. Sapele Road 164, Opposite NPDC, Sapele Road. -

Reproductive Health Knowledge and Practices in Northern Nigeria: Challenging Misconceptions

PATHFINDER INTERNATIONAL Reproductive Health Knowledge and Practices in Northern Nigeria: Challenging Misconceptions The Reproductive Health/Family Planning Service Delivery Project in Northern Nigeria Reproductive Health Knowledge and Practices in Northern Nigeria: Challenging Misconceptions The Reproductive Health/Family Planning Service Delivery Project in Northern Nigeria With Funding From the David and Lucile Packard Foundation Table of Contents Acronyms........................................................................................................................................ 3 Acknowledgments........................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary........................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 6 Study Objectives and Methodology.............................................................................................. 10 Results........................................................................................................................................... 11 Child Spacing........................................................................................................................ 11 Maternal Health................................................................................................................... -

The State and Ecological Problems in Katsina, Nigeria

• A rican Arid Lands Working Paper Series ISSN 1102-4488 NORDISKA AfR\KAINSTITUiEi 1B 2 -02- , , UPPSA\.A Nordiska Afrikainstitutet (The Scandinavian Institute of African Studies) p O Box 1703, S-751 47 UPPSALA, Sweden Telex 8195077, Telefax 018-69 56 29 African Arid Lands Working Paper Series is published within the Nordiska Mrikainstitutet research prograrnrne Human Life in African Arid Lands, the main objectives of which are as follows: to encourage research in the drylands and the exchange of country and regional experiences, and to link up with the ongoing activities in Mrica and the Nordic countries to enhance the cooperation between social and natural science disciplines and indigenous knowledge to explore the hearing of developmental policies on the environment and the possibility of devising long-term strategies for the redemption of the fragile drylands environment Editorial staff: Anders Hjort af Ornäs, Director of Nordiska Afrikainstitutet M.A. Mohamed Salih, Prograrnrne Leader of Human Life in African Arid Lands Eva Lena Volk, Prograrnrne Assistant, Human Life in African Arid Lands illustration on front: Details from a decorated gourd (in Nigeria 's Traditional Crafts by Alison Hodge) A/riean Arid Lands Working Paper Series No. 1/92 THE STATE AND ECOLOGICAL PROBLEMS IN KATSINA, NIGERIA by A. M. SAULAWA Department of History, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, Nigeria. ABSTRACT An important feature in the Nigerian and African past and recent history has been the environment and its continuous inf1uence on the population. This issue is one that is much tied up with the ecological problems and the challenges they pose to the population. -

2021-HAC-Nigeria-May-Update.Pdf

2021 www.unicef.org/appeals/nigeria Humanitarian Action for Children A newborn receives a vaccine at the Major Aminu Primary Health Centre, in Yola, Adamawa, northeast Nigeria. The clinic is one of many that UNICEF has renovated with funds from the European Union. Nigeria HIGHLIGHTS IN NEED An estimated 8.7 million people – including 5.1 million children and over one million people 8.7 5.1 living in inaccessible areas – need humanitarian assistance in northeast Nigeria.1 There are over 600,000 crisis-affected people in the northwest with little access to humanitarian million million 2 support. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has exacerbated 3 4 humanitarian needs and devastated weak service infrastructure. people children UNICEF will provide life-saving assistance to 3.9 million crisis-affected people, including to address severe acute malnutrition (SAM); improve access to safe water and sanitation; provide integrated health services; improve the psychosocial well-being of children and caregivers; and increase access to education. Services will be delivered within the framework of COVID-19 response plans through inter-agency coordination and partnership with the Government and others. 2017 2021 UNICEF requires US$179.2 million to deliver an integrated package of nutrition, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and education services to address the needs of vulnerable TO BE REACHED and crisis-affected children. 3.9 2.3 million million people5 children6 KEY PLANNED TARGETS 419,375 834,585 children admitted for people accessing a 2017 2021 treatment for severe acute sufficient quantity of safe malnutrition water FUNDING REQUIREMENTS US$ 179.2 175,000 761,332 million children/caregivers children accessing accessing mental health educational services and psychosocial support 2017 2021 HUMANITARIAN SITUATION AND NEEDS Over a decade of armed conflict in northeast Nigeria has resulted in large-scale population SECTOR NEEDS displacements.