Reproductive Health Knowledge and Practices in Northern Nigeria: Challenging Misconceptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Technical Committee Om

REPORT OF THE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE ON CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS FOR THE APPLICATION OF SHARIA IN KATSINA STATE January 2000 Contents: Volume I: Main Report Chapter One: Preliminary Matters Preamble Terms of Reference Modus Operandi Chapter Two: Consideration of Various Sections of the Constitution in Relation to Application of Sharia A. Section 4(6) B. Section 5(2) C. Section 6(2) D. Section 10 E. Section 38 F. Section 275(1) G. Section 277 Chapter Three: Observations and Recommendations 1. General Observations 2. Specific Recommendations 3. General Recommendations Conclusion Appendix A: List of all the Groups, Associations, Institutions and Individuals Contacted by the Committee Volume II: Verbatim Proceedings Zone 1: Funtua: Funtua, Bakori, Danja, Faskari, Dandume and Sabuwa Zone 2: Malumfashi: Malumfashi, Kafur, Kankara and Musawa Zone 3: Dutsin-Ma: Dutsin-Ma, Danmusa, Batsari, Kurfi and Safana Zone 4: Kankia: Kankia, Ingawa, Kusada and Matazu Zone 5: Daura: Daura, Baure, Zango, Mai’adua and Sandamu Zone 6: Mani: Mani, Mashi, Dutsi and Bindawa Zone 7: Katsina: Katsina, Kaita, Rimi, Jibia, Charanchi and Batagarawa 1 Ostien: Sharia Implementation in Northern Nigeria 1999-2006: A Sourcebook: Supplement to Chapter 2 REPORT OF THE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE ON APPLICATION OF SHARIA IN KATSINA STATE VOLUME I: MAIN REPORT CHAPTER ONE Preamble The Committee was inaugurated on the 20th October, 1999 by His Excellency, the Governor of Katsina State, Alhaji Umaru Musa Yar’adua, at the Council Chambers, Government House. In his inaugural address, the Governor gave four point terms of reference to the Committee. He urged members of the Committee to work towards realising the objectives for which the Committee was set up. -

Monetering of Infectious Diseases in Katsina and Daura Zones of Katsina State: a Clustering Analysis

Available online at http://www.ajol.info/index.php/njbas/index Nigerian Journal of Basic and Applied Science (2011), 19 (1): 31-42 ISSN 0794-5698 Monetering of Infectious Diseases in Katsina and Daura Zones of Katsina State: A Clustering Analysis 1U. Dauda, 2S.U. Gulumbe, *2M. Yakubu and 1L.K. Ibrahim 1Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, Umaru Musa Yar’aduwa University, Katsina. 2Department of mathematics Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto Nigeria [*Corresponding Author: [email protected]] ABSTRACT: In this paper, data of infectious diseases were collected from the two senatorial zones of Katsina state, and analyzed using cluster analysis, a multivariate technique. This necessitated a partition of the set of diseases into groups such that the diseases with similar degree of prevalence were identified. The result of the cluster formation shows that Malaria is more prevalent in all of the two zones, followed by Cholera and Typhoid fever using the Single Linkage and Centroid methods. The Complete Linkage and Ward methods showed that Malaria is the most prevalent followed by Typhoid fever and Cholera in Katsina zone, while in Daura zone Typhoid fever is more prevalent followed by Malaria and Cholera. The number of clusters tends to vary from one zone to another. This is achieved by using Chi-square test for independence. The study concludes that the use of clustering methods provides a suitable tool for assessing the level of infections of the disease. Keywords: Cluster analysis, Infectious diseases, Malaria, Cholera and Typhoid INTRODUCTION important is that it is caused by living One of the most challenging tasks to public health microorganisms which can usually be identified, in Nigeria and Africa in general, is the control of thus establishing the aetiology early in the illness. -

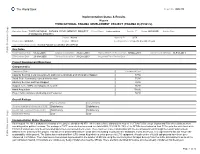

The World Bank Implementation Status & Results

The World Bank Report No: ISR4370 Implementation Status & Results Nigeria THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (FADAMA III) (P096572) Operation Name: THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 7 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: (FADAMA III) (P096572) Country: Nigeria Approval FY: 2009 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): National Fadama Coordination Office(NFCO) Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 01-Jul-2008 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date 07-Nov-2011 Last Archived ISR Date 11-Feb-2011 Effectiveness Date 23-Mar-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Capacity Building, Local Government, and Communications and Information Support 87.50 Small-Scale Community-owned Infrastructure 75.00 Advisory Services and Input Support 39.50 Support to the ADPs and Adaptive Research 36.50 Asset Acquisition 150.00 Project Administration, Monitoring and Evaluation 58.80 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Low Low Implementation Status Overview As at August 19, 2011, disbursement status of the project stands at 46.87%. All the states have disbursed to most of the FCAs/FUGs except Jigawa and Edo where disbursement was delayed for political reasons. The savings in FUEF accounts has increased to a total ofN66,133,814.76. 75% of the SFCOs have federated their FCAs up to the state level while FCAs in 8 states have only been federated up to the Local Government levels. -

Violence in Nigeria's North West

Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem Africa Report N°288 | 18 May 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Community Conflicts, Criminal Gangs and Jihadists ...................................................... 5 A. Farmers and Vigilantes versus Herders and Bandits ................................................ 6 B. Criminal Violence ...................................................................................................... 9 C. Jihadist Violence ........................................................................................................ 11 III. Effects of Violence ............................................................................................................ 15 A. Humanitarian and Social Impact .............................................................................. 15 B. Economic Impact ....................................................................................................... 16 C. Impact on Overall National Security ......................................................................... 17 IV. ISWAP, the North West and -

IOM Nigeria DTM Flash Report NCNW 37 (31 January 2021)

FLASH REPORT #37: POPULATION DISPLACEMENT DTM North West/North Central Nigeria Nigeria 25 - 31 JANUARY 2021 Casualties: Movement Trigger: 160 Individuals 9 Individuals Armed attacks OVERVIEW The crisis in Nigeria’s North Central and North West zones, which involves long-standing tensions between NIGER REPUBLIC ethnic and religious groups; attacks by criminal Kaita Mashi Mai'adua Jibia groups; and banditry/hirabah (such as kidnapping and Katsina Daura Zango Dutsi Faskari Batagarawa Mani Rimi Safana grand larceny along major highways) led to a fresh Batsari Baure Bindawa wave of population displacement. 134 Kurfi Charanchi Ingawa Sandamu Kusada Dutsin-Ma Kankia Following these events, a rapid assessment was Katsina Matazu conducted by DTM (Displacement Tracking Matrix) Dan Musa Jigawa Musawa field staff between 25 and 31 January 2021, with the Kankara purpose of informing the humanitarian community Malumfashi Katsina Kano Faskari Kafur and government partners in enabling targeted Bakori response. Flash reports utilise direct observation and Funtua Dandume Danja a broad network of key informants to gather represen- Sabuwa tative data and collect information on the number, profile and immediate needs of affected populations. NIGERIA Latest attacks affected 160 individuals, including 14 injuries and 9 fatalities, in Makurdi LGA of Benue State and Faskari LGA of Katsina State. The attacks caused Kaduna people to flee to neighbouring localities. SEX (FIG. 1) Plateau Federal Capital Territory 39% Nasarawa X Affected Population 61% Male Makurdi International border Female 26 State Guma Agatu Benue Makurdi LGA Apa Gwer West Tarka Oturkpo Gwer East Affected LGAs Gboko Ohimini Konshisha Ushongo The map is for illustration purposes only. -

Surviving Works: Context in Verre Arts Part One, Chapter One: the Verre

Surviving Works: context in Verre arts Part One, Chapter One: The Verre Tim Chappel, Richard Fardon and Klaus Piepel Special Issue Vestiges: Traces of Record Vol 7 (1) (2021) ISSN: 2058-1963 http://www.vestiges-journal.info Preface and Acknowledgements (HTML | PDF) PART ONE CONTEXT Chapter 1 The Verre (HTML | PDF) Chapter 2 Documenting the early colonial assemblage – 1900s to 1910s (HTML | PDF) Chapter 3 Documenting the early post-colonial assemblage – 1960s to 1970s (HTML | PDF) Interleaf ‘Brass Work of Adamawa’: a display cabinet in the Jos Museum – 1967 (HTML | PDF) PART TWO ARTS Chapter 4 Brass skeuomorphs: thinking about originals and copies (HTML | PDF) Chapter 5 Towards a catalogue raisonnée 5.1 Percussion (HTML | PDF) 5.2 Personal Ornaments (HTML | PDF) 5.3 Initiation helmets and crooks (HTML | PDF) 5.4 Hoes and daggers (HTML | PDF) 5.5 Prestige skeuomorphs (HTML | PDF) 5.6 Anthropomorphic figures (HTML | PDF) Chapter 6 Conclusion: late works ̶ Verre brasscasting in context (HTML | PDF) APPENDICES Appendix 1 The Verre collection in the Jos and Lagos Museums in Nigeria (HTML | PDF) Appendix 2 Chappel’s Verre vendors (HTML | PDF) Appendix 3 A glossary of Verre terms for objects, their uses and descriptions (HTML | PDF) Appendix 4 Leo Frobenius’s unpublished Verre ethnological notes and part inventory (HTML | PDF) Bibliography (HTML | PDF) This work is copyright to the authors released under a Creative Commons attribution license. PART ONE CONTEXT Chapter 1 The Verre Predominantly living in the Benue Valley of eastern middle-belt Nigeria, the Verre are one of that populous country’s numerous micro-minorities. -

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: an Historical Analysis, 1804-1960

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: An Historical Analysis, 1804-1960 by Kari Bergstrom Michigan State University Winner of the Rita S. Gallin Award for the Best Graduate Student Paper in Women and International Development Working Paper #276 October 2002 Abstract This paper looks at the effects of Islamization and colonialism on women in Hausaland. Beginning with the jihad and subsequent Islamic government of ‘dan Fodio, I examine the changes impacting Hausa women in and outside of the Caliphate he established. Women inside of the Caliphate were increasingly pushed out of public life and relegated to the domestic space. Islamic law was widely established, and large-scale slave production became key to the economy of the Caliphate. In contrast, Hausa women outside of the Caliphate were better able to maintain historical positions of authority in political and religious realms. As the French and British colonized Hausaland, the partition they made corresponded roughly with those Hausas inside and outside of the Caliphate. The British colonized the Caliphate through a system of indirect rule, which reinforced many of the Caliphate’s ways of governance. The British did, however, abolish slavery and impose a new legal system, both of which had significant effects on Hausa women in Nigeria. The French colonized the northern Hausa kingdoms, which had resisted the Caliphate’s rule. Through patriarchal French colonial policies, Hausa women in Niger found they could no longer exercise the political and religious authority that they historically had held. The literature on Hausa women in Niger is considerably less well developed than it is for Hausa women in Nigeria. -

Nigeria Update to the IMB Nigeria

Progress in Polio Eradication Initiative in Nigeria: Challenges and Mitigation Strategies 16th Independent Monitoring Board Meeting 1 November 2017 London 0 Outline 1. Epidemiology 2. Challenges and Mitigation strategies SIAs Surveillance Routine Immunization 3. Summary and way forward 1 Epidemiology 2 Polio Viruses in Nigeria, 2015-2017 Past 24 months Past 12 months 3 Nigeria has gone 13 months without Wild Polio Virus and 11 months without cVDPV2 13 months without WPV 11 months – cVDPV2 4 Challenges and Mitigation strategies 5 SIAs 6 Before the onset of the Wild Polio Virus Outbreak in July 2016, there were several unreached settlements in Borno Borno Accessibility Status by Ward, March 2016 # of Wards in % Partially LGAs % Fully Accessible % Inaccessible LGA Accessible Abadam 10 0% 0% 100% Askira-Uba 13 100% 0% 0% Bama 14 14% 0% 86% Bayo 10 100% 0% 0% Biu 11 91% 9% 0% Chibok 11 100% 0% 0% Damboa 10 20% 0% 80% Dikwa 10 10% 0% 90% Gubio 10 50% 10% 40% Guzamala 10 0% 0% 100% Gwoza 13 8% 8% 85% Hawul 12 83% 17% 0% Jere 12 50% 50% 0% Kaga 15 0% 7% 93% Kala-Balge 10 0% 0% 100% Konduga 11 0% 64% 36% Kukawa 10 20% 0% 80% Kwaya Kusar 10 100% 0% 0% Mafa 12 8% 0% 92% Magumeri 13 100% 0% 0% Maiduguri 15 100% 0% 0% Marte 13 0% 0% 100% Mobbar 10 0% 0% 100% Monguno 12 8% 0% 92% Ngala 11 0% 0% 100% Nganzai 12 17% 0% 83% Shani 11 100% 0% 0% State 311 41% 6% 53% 7 Source: Borno EOC Data team analysis Four Strategies were deployed to expand polio vaccination reach and increase population immunity in Borno state SIAs RES2 RIC4 Special interventions 12 -

IOM Nigeria DTM Flash Report NCNW 26 June 2020

FLASH REPORT: POPULATION DISPLACEMENT DTM North West/North Central Nigeria. Nigeria 22 - 26 JUNE 2020 Aected Population: Casualties: Movement Trigger: 2,349 Individuals 3 Individuals Armed attacks OVERVIEW Maikwama 219 The crisis in Nigeria’s North Central and North West zones, which involves long-standing Dandume tensions between ethnic and linguis�c groups; a�acks by criminal groups; and banditry/hirabah (such as kidnapping and grand larceny along major highways) led to fresh wave of popula�on displacement. Kaita Mashi Mai'adua Jibia Shinkafi Katsina Daura Zango Dutsi Batagarawa Mani Safana Latest a�acks affected 2,349 individuals, includ- Zurmi Rimi Batsari Baure Maradun Bindawa Kurfi ing 18 injuries and 3 fatali�es, in Dandume LGA Bakura Charanchi Ingawa Jigawa Kaura Namoda Sandamu Katsina Birnin Magaji Kusada Dutsin-Ma Kankia (Katsina) and Bukkuyum LGA (Zamfara) between Talata Mafara Bungudu Matazu Dan Musa 22 - 26 June, 2020. The a�acks caused people to Gusau Zamfara Musawa Gummi Kankara flee to neighboring locali�es. Bukkuyum Anka Tsafe Malumfashi Kano Faskari Kafur Gusau Bakori A rapid assessment was conducted by field staff Maru Funtua Dandume Danja to assess the impact on people and immediate Sabuwa needs. ± GENDER (FIG. 1) Kaduna X Affected PopulationPlateau 42% Kyaram 58% Male State Bukkuyum 2,130 Female Federal Capital Territory LGA Nasarawa Affected LGAs The map is for illustration purposes only. The depiction and use of boundaries, geographic names and related data shown are not warranted to be error free nor do they imply judgment on the legal status of any territory, or any endorsement or accpetance of such boundaries by MOST NEEDED ASSISTANCE (FIG. -

First State Integrity Meeting in Katsina

First State Integrity Meeting in Katsina Edited and co-auhtored by; Petter Langseth and Oliver Stolpe UNODC’s Global Programme against Corruption Katsina, 18-19 June 2003 Disclaimer The views expressed herein are those of the authors and editors and not necessarily those of the United Nations 2 TABLE OF CONTENT I. FOREWORD............................................................................................................... 4 II. OVERVIEW................................................................................................................. 5 A. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 5 B. Origins of the initiative.............................................................................................. 5 C. The way forward in Nigeria ....................................................................................... 6 D. The First Judicial Integrity Meeting.......................................................................... 6 E. Follow-up action identified in the course of the Workshop....................................... 7 III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY......................................................................................... 10 A. The State Integrity Meeting...................................................................................... 10 B. Conclusions and Recommendations ....................................................................... 10 C. Katsina State. Summary Anti Corruption Action Plan ........................................... -

2018/2019 Annual School Census Report

Foreword Successful education policies are formed and supported by accurate, timely and reliable data, to improve governance practices, enhance accountability and ultimately improve the teaching and learning process in schools. Considering the importance of robust data collection, the Planning, Research and Statistics (PRS) Department, Katsina State Ministry of Education prepares and publishes the Annual Schools Census Statistical Report of both Public and Private Schools on an annual basis. This is in compliance with the National EMIS Policy and its implementation. The Annual Schools Census Statistical Report of 2018-2019 is the outcome of the exercise conducted between May and June 2019, through a rigorous activities that include training Head Teachers and Teachers on School Records Keeping; how to fill ASC questionnaire using school records; data collection, validation, entry, consistency checks and analysis. This publication is the 13th Annual Schools Census Statistical Report of all Schools in the State. In line with specific objectives of National Education Management Information System (NEMIS), this year’s ASC has obtained comprehensive and reliable data where by all data obtained were from the primary source (the school’s head provide all data required from schools records). Data on Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) of basic education and post basic to track the achievement of the State Education Sector Operational Plan (SESOP) as well as Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); feed data into the National databank to strengthen NEMIS for national and global reporting. The report comprises of educational data pertaining to all level both public and private schools ranging from pre-primary, primary, junior secondary and senior secondary level. -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT FEBRUARY 13, 2019 S/N Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 4 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 5 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 6 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 7 Above Only Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Benson Idahosa University Campus, Ugbor GRA, Benin EDO Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank 8 Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi BAUCHI 9 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 10 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 11 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 12 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 13 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 14 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. Area, Nasarawa State NASSARAWA 15 Adazi-Enu Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Nkwor Market Square, Adazi- Enu, Anaocha Local Govt, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 16 Adazi-Nnukwu Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Near Eke Market, Adazi Nnukwu, Adazi, Anambra State ANAMBRA 17 Addosser Microfinance Bank Limited State 32, Lewis Street, Lagos Island, Lagos State LAGOS 18 Adeyemi College Staff Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Adeyemi College of Education Staff Ni 1, CMS Ltd Secretariat, Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo ONDO 19 Afekhafe Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit No.