Nigeria's Interminable Insurgency ? : Addressing the Boko Haram Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISIS in Africa: Implications from Syria and Iraq Dr

ISIS in Africa: Implications from Syria and Iraq Dr. Joseph Siegle28 Africa Center for Strategic Studies National Defense University At the end of 2016, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, leader of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), announced that the group had “expanded and shifted some of our command, media, and wealth to Africa.” ISIS’s Dabiq magazine referred to the regions of Africa that were part of its “caliphate:” “the region that includes Sudan, Chad and Egypt has been named the caliphate province of Alkinaana; the region that includes Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya and Uganda as the province of Habasha; the North African region encompassing Libya, Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Nigeria, Niger and Mauritania as Maghreb, the province of the caliphate.” Leaving aside the mismatched ethno-linguistic groupings included in each of these “provinces,” ISIS’s interest in establishing a presence in Africa has long been a part of its vision for a global caliphate. Battlefield setbacks in ISIS’s strongholds in Iraq and Syria since 2015, however, raise questions of what impact this will have for ISIS’s African aspirations. A useful starting point in considering this question is to recognize that the threat from violent Islamist groups in Africa is not monolithic but is comprised of a variety of distinct entities. For the most part, these groups are geographically concentrated and focused on local territorial or political objectives. Specifically, the Africa Center for Strategic Studies has identified 5 major categories of militant Islamists groups in Africa (see map): http://africacenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Africas-Active-Militant-Islamist- Groups-November-2016.pdf. -

BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S

112TH CONGRESS COMMITTEE " COMMITTEE PRINT ! 1st Session PRINT 112–B BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S. Homeland SUBCOMMITTEE ON COUNTERTERRORISM AND INTELLIGENCE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES December 2011 FIRST SESSION U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 71–725 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman LAMAR SMITH, Texas BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California LORETTA SANCHEZ, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas HENRY CUELLAR, Texas GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York PAUL C. BROUN, Georgia LAURA RICHARDSON, California CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois TIM WALBERG, Michigan BRIAN HIGGINS, New York CHIP CRAVAACK, Minnesota JACKIE SPEIER, California JOE WALSH, Illinois CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania HANSEN CLARKE, Michigan BEN QUAYLE, Arizona WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia KATHLEEN C. HOCHUL, New York BILLY LONG, Missouri VACANCY JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas MO BROOKS, Alabama MICHAEL J. RUSSELL, Staff Director & Chief Counsel KERRY ANN WATKINS, Senior Policy Director MICHAEL S. TWINCHEK, Chief Clerk I. LANIER AVANT, Minority Staff Director (II) C O N T E N T S BOKO HARAM EMERGING THREAT TO THE U.S. HOMELAND I. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 II. Findings .............................................................................................................. -

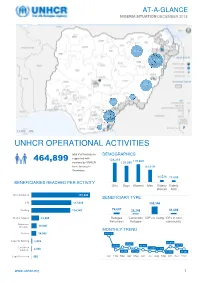

Unhcr Operational Activities 464,899

AT-A-GLANCE NIGERIA SITUATION DECEMBER 2018 28,280 388,208 20,163 1,770 4,985 18.212 177 Bénéficiaires Reached UNHCR OPERATIONAL ACTIVITIES total # of individuals DEMOGRAPHICS supported with 464,899 128,318 119,669 services by UNHCR 109,080 from January to 81,619 December; 34,825 of them from Mar-Apr 14,526 11,688 2018 BENEFICIARIES REACHED PER ACTIVITY Girls Boys Women Men Elderly Elderly Women Men Documentation 172,800 BENEFICIARY TYPE CRI 117,838 308,346 Profiling 114,747 76,607 28,248 51,698 Shelter Support 22,905 Refugee Cameroon IDPs in Camp IDPs in host Returnees Refugee community Awareness Raising 16,000 MONTHLY TREND Referral 14,956 140,116 Capacity Building 2,939 49,819 39,694 24,760 25,441 34,711 Livelihood 11,490 11,158 Support 2,048 46,139 37,118 13,770 30,683 Legal Protection 666 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec www.unhcr.org 1 NIGERIA SITUATION AT-A-GLANCE / DEC 2018 CORE UNHCR INTERVENTIONS IN NIGERIA UNHCR Nigeria strategy is based on the premise that the government of Nigeria assumes the primary responsibility to provide protection and assistance to persons of concern. By building and reinforcing self-protection mechanisms, UNHCR empowers persons of concern to claim their rights and to participate in decision-making, including with national and local authorities, and with humanitarian actors. The overall aim of UNHCR Nigeria interventions is to prioritize and address the most serious human rights violations, including the right to life and security of persons. -

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’S Enduring Insurgency

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Editor: Jacob Zenn Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Jacob Zenn (Editor) Abdulbasit Kassim Elizabeth Pearson Atta Barkindo Idayat Hassan Zacharias Pieri Omar Mahmoud Combating Terrorism Center at West Point United States Military Academy www.ctc.usma.edu The views expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Combating Terrorism Center, United States Military Academy, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government. May 2018 Cover Photo: A group of Boko Haram fighters line up in this still taken from a propaganda video dated March 31, 2016. COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Director The editor thanks colleagues at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point (CTC), all of whom supported this endeavor by proposing the idea to carry out a LTC Bryan Price, Ph.D. report on Boko Haram and working with the editor and contributors to see the Deputy Director project to its rightful end. In this regard, I thank especially Brian Dodwell, Dan- iel Milton, Jason Warner, Kristina Hummel, and Larisa Baste, who all directly Brian Dodwell collaborated on the report. I also thank the two peer reviewers, Brandon Kend- hammer and Matthew Page, for their input and valuable feedback without which Research Director we could not have completed this project up to such a high standard. There were Dr. Daniel Milton numerous other leaders and experts at the CTC who assisted with this project behind-the-scenes, and I thank them, too. Distinguished Chair Most importantly, we would like to dedicate this volume to all those whose lives LTG (Ret) Dell Dailey have been afected by conflict and to those who have devoted their lives to seeking Class of 1987 Senior Fellow peace and justice. -

Iom Shelter Needs Assessment in Return Areas: Adamawa State

International Organization for Migration IOM SHELTER NEEDS ASSESSMENT IN RETURN AREAS: ADAMAWA STATE October 2017 Shelter Needs Assessment Report IOM Shelter Needs Assessment in Return Areas: Adamawa State Table of Content BACKGROUND ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 OBJECTIVE ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 COVERAGE ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 METHODOLOGY ……………………………………………………………………………….. 5 FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS Demographic Profile …………………………………………………………………………. 6 Housing, Land and Property ………………………………………………………………… 13 Housing Condition ……………………………………………………………………………18 Damage Assessment …………………………………………………………………………22 Access to Other Services …………………………………………………………………….29 RECOMMENDATIONS …………………………………………………………………………. 35 Page 1 IOM Shelter Needs Assessment in Return Areas: Adamawa State BACKGROUND In North-Eastern Nigeria, attacks and counter attacks have resulted in prolonged insecurity and endemic violations of human rights, triggering waves of forced displacement. Almost two million people remain displaced in Nigeria, and displacement continues to be a significant factor in 2017. Since late 2016, IOM and other humanitarian partners have been able to scale up on its activities. However, despite the will and hope of the humanitarian community and the Government of Nigeria and the dedication of teams and humanitarian partners in supporting them, humanitarian needs have drastically increased and the humanitarian response needs to keep scaling up to reach all the affected population in need. While the current humanitarian -

Main Events Facilitated by the Nigeria Tropical Biology Association from 2016-2020

MAIN EVENTS FACILITATED BY THE NIGERIA TROPICAL BIOLOGY ASSOCIATION FROM 2016-2020 Programmes held from 2015-2017 1. 4th Biodiversity Conservation Conference held at the Federal University of Technology, Akure. 2015. 2. 5th/Joint Biodiversity Conservation Conference in celebration of 10th Anniversary of Nigeria Tropical Biology Association (NTBA) and Maiden Conference of Nigeria Chapter of Society for Conservation Biology (NSCB). Conference Theme: MDGs to SDGs: Towards Sustainable Biodiversity Conservation in Nigeria Venue: Main Auditorium, University of Ilorin Date: 20 – 24 June, 2016 Dr. Joseph Onoja: Keynote Speaker at Joint Participants at the Joint Conference 2016 NTBA/NSCB Biodiversity Conservation Conference Programmes and Projects conducted 2018-2020 1. A National Student Essay Competition for final year undergraduate and master's students in Biology-related disciplines. This was conducted in August-October, 2018. The best four competitors were invited and sponsored by NTBA to attend and make oral presentation of their essays during the 6th Biodiversity Conservation Conference in Federal University, Dutse, Jigawa State. 2. The 6th Biodiversity Conservation Conference was held on 7th -11th April, 2019 at the Federal University Dutse, Jigawa State. The Opening Ceremony was attended by high profile community leaders and academics, conservation professionals and students. The conference was a success with a total of 111 registered participants, and many Oral presentations on different aspects of 1 biodiversity and conservation as affected by the increasing human population. The keynote speaker and the NTBA President also had the pleasure of being interviewed by the Nigerian Television Authority (NTA) Crew, and this was reported by the NTA Network. The event was also reported in the April edition of the University Newsletter. -

Lessons from Colombia for Curtailing the Boko Haram Insurgency in Nigeria

Lessons From Colombia For Curtailing The Boko Haram Insurgency In Nigeria BY AFEIKHENA JEROME igeria is a highly complex and ethnically diverse country, with over 400 ethnic groups. This diversity is played out in the way the country is bifurcated along the lines of reli- Ngion, language, culture, ethnicity and regional identity. The population of about 178.5 million people in 2014 is made up of Christians and Muslims in equal measures of about 50 percent each, but including many who embrace traditional religions as well. The country has continued to experience serious and violent ethno-communal conflicts since independence in 1960, including the bloody and deadly thirty month fratricidal Civil War (also known as the Nigerian-Biafran war, 1967-70) when the eastern region of Biafra declared its seces- sion and which claimed more than one million lives. The most prominent of these conflicts recently pitch Muslims against Christians in a dangerous convergence of religion, ethnicity and politics. The first and most dramatic eruption in a series of recent religious disturbances was the Maitatsine uprising in Kano in December 1980, in which about 4,177 died. While the exact number of conflicts in Nigeria is unknown, because of a lack of reliable sta- tistical data, it is estimated that about 40 percent of all conflicts have taken place since the coun- try’s return to civilian rule in 1999.1 The increasing wave of violent conflicts across Nigeria under the current democratic regime is no doubt partly a direct consequence of the activities of ethno- communal groups seeking self-determination in their “homelands,” and of their surrogate ethnic militias that have assumed prominence since the last quarter of 2000. -

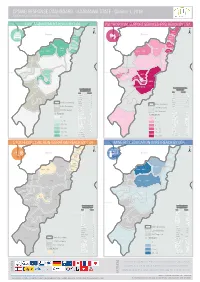

CPSWG RESPONSE DASHBOARD - ADAMAWA STATE - Quarter 1, 2019 Child Protection Sub Working Group, Nigeria

CPSWG RESPONSE DASHBOARD - ADAMAWA STATE - Quarter 1, 2019 Child Protection Sub Working Group, Nigeria YobeCASE MANAGEMENT REACH BY LGA PSYCHOSOCIALYobe SUPPORT SERVICES (PSS) REACH BY LGA 78% 14% Madagali ± Madagali ± Borno Borno Michika Michika 86% 10% 82% 16% Mubi North Mubi North Hong 100% Mubi South 5% Hong Gombi 100% 100% Gombi 10% 27% Mubi South Shelleng Shelleng Guyuk Song 0% Guyuk Song 0% 0% Maiha 0% Maiha Chad Chad Lamurde 0% Lamurde 0% Nigeria Girei Nigeria Girei 36% 81% 11% 96% Numan 0% Numan 0% Yola North Demsa 100% Demsa 26% Yola North 100% 0% Adamawa Fufore Yola South 0% Yola South 100% Fufore Mayo-Belwa Mayo-Belwa Adamawa Local Government Area Local Government (LGA) Target Area (LGA) Target LGA TARGET LGA TARGET Demsa 1,170 DEMSA 78 Fufore 370 Jada FUFORE 41 Jada Ganye 0 GANYE 0 Girei 933 GIREI 16 Gombi 4,085 State Boundary GOMBI 33 State Boundary Guyuk 0 GUYUK 0 LGA Boundary Hong 16,941 HONG 6 Ganye Ganye LGA Boundary Jada 0 JADA 0 Not Targeted Lamurde 839 LAMURDE 6 Not Targeted Madagali 6,321 MADAGALI 119 % Reach Maiha 2,800 MAIHA 12 % REACH Mayo-Belwa 0 0 MAYO - BELWA 0 0 Michika 27,946 Toungo 0% MICHIKA 232 Toungo 0% 1 - 36 Mubi North 11,576 MUBI NORTH 154 1 - 5 Mubi South 11,821 MUBI SOUTH 139 37 - 78 Numan 2,250 NUMAN 14 6 - 11 Shelleng 0 SHELLENG 0 79 - 82 12 - 16 Song 1,437 SONG 21 Teungo 25 83 - 86 TOUNGO 6 17 - 27 Yola North 1,189 YOLA NORTH 14 Yola South 2,824 87 - 100 YOLA SOUTH 47 28 - 100 SOCIO-ECONOMICYobe REINTEGRATION REACH BY LGA MINEYobe RISK EDUCATION (MRE) REACH BY LGA Madagali Madagali R 0% I 0% ± -

An Analysis of What Works and What Doesn't

Radicalisation and Deradicalisation in Nigeria: An Analysis of What Works and What Doesn’t Nasir Abubakar Daniya i Radicalisation and Deradicalisation in Nigeria: An Analysis of What Works and What Doesn’t. Nasir Abubakar Daniya Student Number: 13052246 A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of Requirements for award of: Professional Doctorate Degree in Policing Security and Community Safety London Metropolitan University Faculty of Social Science and Humanities March 2021 Thesis word count: 104, 482 ii Abstract Since Nigeria’s independence from Britain in 1960, the country has made some progress while also facing some significant socio-economic challenges. Despite being one of the largest producers of oil in the world, in 2018 and 2019, the Brooking Institution and World Poverty Clock respectively ranked Nigeria amongst top three countries with extreme poverty in the World. Muslims from the north and Christians from the south dominate the country; each part has its peculiar problem. There have been series of agitations by the militants from the south to break the country due to unfair treatments by the Nigerian government. They produced multiple violent groups that killed people and destroyed properties and oil facilities. In the North, an insurgent group called Boko Haram emerges in 2009; they advocated for the establishment of an Islamic state that started with warning that, western education is prohibited. Reports say the group caused death of around 100,000 and displaced over 2 million people. As such, Niger Delta Militancy and Boko Haram Insurgency have been major challenges being faced by Nigeria for about a decade. To address such challenges, the Nigerian government introduced separate counterinsurgency interventions called Presidential Amnesty Program (PAP) and Operation Safe Corridor (OSC) in 2009 and 2016 respectively, which are both aimed at curtailing Militancy and Insurgency respectively. -

Sunni Suicide Attacks and Sectarian Violence

Terrorism and Political Violence ISSN: 0954-6553 (Print) 1556-1836 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ftpv20 Sunni Suicide Attacks and Sectarian Violence Seung-Whan Choi & Benjamin Acosta To cite this article: Seung-Whan Choi & Benjamin Acosta (2018): Sunni Suicide Attacks and Sectarian Violence, Terrorism and Political Violence, DOI: 10.1080/09546553.2018.1472585 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1472585 Published online: 13 Jun 2018. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ftpv20 TERRORISM AND POLITICAL VIOLENCE https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1472585 Sunni Suicide Attacks and Sectarian Violence Seung-Whan Choi c and Benjamin Acosta a,b aInterdisciplinary Center Herzliya, Herzliya, Israel; bInternational Institute for Counter-Terrorism, Herzliya, Israel; cPolitical Science, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA ABSTRACT KEY WORDS Although fundamentalist Sunni Muslims have committed more than Suicide attacks; sectarian 85% of all suicide attacks, empirical research has yet to examine how violence; Sunni militants; internal sectarian conflicts in the Islamic world have fueled the most jihad; internal conflict dangerous form of political violence. We contend that fundamentalist Sunni Muslims employ suicide attacks as a political tool in sectarian violence and this targeting dynamic marks a central facet of the phenomenon today. We conduct a large-n analysis, evaluating an original dataset of 6,224 suicide attacks during the period of 1980 through 2016. A series of logistic regression analyses at the incidence level shows that, ceteris paribus, sectarian violence between Sunni Muslims and non-Sunni Muslims emerges as a substantive, signifi- cant, and positive predictor of suicide attacks. -

Volume 7: Shaping Global Islamic Discourses : the Role of Al-Azhar, Al-Medina and Al-Mustafa Masooda Bano Editor

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eCommons@AKU eCommons@AKU Exploring Muslim Contexts ISMC Series 3-2015 Volume 7: Shaping Global Islamic Discourses : The Role of al-Azhar, al-Medina and al-Mustafa Masooda Bano Editor Keiko Sakurai Editor Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_emc Recommended Citation Bano, M. , Sakurai, K. (Eds.). (2015). Volume 7: Shaping Global Islamic Discourses : The Role of al-Azhar, al-Medina and al-Mustafa Vol. 7, p. 242. Available at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_emc/9 Shaping Global Islamic Discourses Exploring Muslim Contexts Series Editor: Farouk Topan Books in the series include Development Models in Muslim Contexts: Chinese, “Islamic” and Neo-liberal Alternatives Edited by Robert Springborg The Challenge of Pluralism: Paradigms from Muslim Contexts Edited by Abdou Filali-Ansary and Sikeena Karmali Ahmed Ethnographies of Islam: Ritual Performances and Everyday Practices Edited by Badouin Dupret, Thomas Pierret, Paulo Pinto and Kathryn Spellman-Poots Cosmopolitanisms in Muslim Contexts: Perspectives from the Past Edited by Derryl MacLean and Sikeena Karmali Ahmed Genealogy and Knowledge in Muslim Societies: Understanding the Past Edited by Sarah Bowen Savant and Helena de Felipe Contemporary Islamic Law in Indonesia: Shariah and Legal Pluralism Arskal Salim Shaping Global Islamic Discourses: The Role of al-Azhar, al-Medina and al-Mustafa Edited by Masooda Bano and Keiko Sakurai www.euppublishing.com/series/ecmc -

FEWS NET Special Report: a Famine Likely Occurred in Bama LGA and May Be Ongoing in Inaccessible Areas of Borno State

December 13, 2016 A Famine likely occurred in Bama LGA and may be ongoing in inaccessible areas of Borno State This report summarizes an IPC-compatible analysis of Local Government Areas (LGAs) and select IDP concentrations in Borno State, Nigeria. The conclusions of this report have been endorsed by the IPC’s Emergency Review Committee. This analysis follows a July 2016 multi-agency alert, which warned of Famine, and builds off of the October 2016 Cadre Harmonisé analysis, which concluded that additional, more detailed analysis of Borno was needed given the elevated risk of Famine. KEY MESSAGES A Famine likely occurred in Bama and Banki towns during 2016, and in surrounding rural areas where conditions are likely to have been similar, or worse. Although this conclusion cannot be fully verified, a preponderance of the available evidence, including a representative mortality survey, suggests that Famine (IPC Phase 5) occurred in Bama LGA during 2016, when the vast majority of the LGA’s remaining population was concentrated in Bama Town and Banki Town. Analysis indicates that at least 2,000 Famine-related deaths may have occurred in Bama LGA between January and September, many of them young children. Famine may have also occurred in other parts of Borno State that were inaccessible during 2016, but not enough data is available to make this determination. While assistance has improved conditions in accessible areas of Borno State, a Famine may be ongoing in inaccessible areas where conditions could be similar to those observed in Bama LGA earlier this year. Significant assistance in Bama Town (since July) and in Banki Town (since August/September) has contributed to a reduction in mortality and the prevalence of acute malnutrition, though these improvements are tenuous and depend on the continued delivery of assistance.