The Proof of a Good Idea Is It Survives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mayor's Economy

20091012-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 10/9/2009 7:34 PM Page 1 INSIDE REPORT TOP STORIES SMALL BUSINESS Enough shouting! The CIT grabs headlines, cold, hard facts on but local rivals health care reform grab its customers ® PAGE 17 PAGE 2 Brooklyn faces VOL. XXV, NO. 41 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM OCTOBER 12-18, 2009 PRICE: $3.00 looming luxury rentals A + B deluge C C PAGE 2 LOOK WHO Museums build big shows around single works of art REMADE Mayor’s PAGE 3 BURDEN. AND THEN SOME: economy: Why analysts see The city’s planner-in- chief will rezone her six more losing 100th neighborhood Grades quarters for Citi NEW YORK this week. IN THE MARKETS, PAGE 4 are in The strongest hand Socialite-slash-planning Bloomberg gets for Aqueduct casino commish Amanda Burden an A for quality of EDITORIAL, PAGE 10 has rezoned a fifth of the city, life, a C for budget championed good design and driven big developers nuts BY DANIEL MASSEY when mayor Michael Bloomberg BY THERESA AGOVINO announced last October that he wanted to change the law so he when amanda burden was 12, her step- could run for a third term,he argued father, CBS founder William Paley, that his experience as “a business- turned the front lawn of the family’s Man- man with expertise on Wall Street hasset, Long Island, home into a testing and finance” would help the city confront an unprecedented eco- ground. He littered the yard with massive nomic crisis. A year later, the local BUSINESS LIVES granite models of the skyscraper he was unemployment rate is 10.3%,a 16- GOTHAM GIGS building to house his company in mid- year high. -

Boy Scouts Drops

VOLUME 19, ISSUE 19 WAY OF LIFE MAY 11, 2018 FRIDAY CHURCH NEWS NOTES U2 COMES OUT AS PRO-ABORTION The influential Irish rock band U2 has tweeted support for repealing Ireland’s pro-life Eighth Amendment and legalizing abortion on demand. The amendment guarantees pre-born humans the right to life (“U2 Comes Out,” LifeSiteNews.com, May 2, 2018). The vote will occur on May 25. Three members of the band claim to be Christians, including the frontman Bono. U2 has a great influence in the contemporary worship movement. Bono is praised almost universally among contemporary and emerging Christians. Phil Johnson observes that “Bono seems to be the chief theologian of the Emerging Church Movement” (Absolutely Not! Exposing the Post- modern Errors of the Emerging Church, p. 9). Eugene Peterson, author of The Message, says U2 has a prophetic voice to the world; Bono fom U2 continued on next page... BOY SCOUTS DROPS “BOY” In a major sign of the times, the venerable 108-year- bands asunder, and cast away their cords from old Boy Scouts of America organization is dropping us” (Psalm 2:1-3). As pilgrims in a foreign land, God’s “Boy” from its “Boy Scouts” program to make way for people must refuse to be conformed to the world’s the introduction of girls. Chief Scout Executive Mike thinking and ways. “And be not conformed to this Surbaugh said, “We’re trying to find the right way to world: but be ye transformed by the renewing of your say we’re here for both young men and young mind, that ye may prove what is that good, and women” (“Boy Scouts to change name,” Fox News, acceptable, and perfect, will of God” (Romans 12:2). -

“The Greatest Gift Is the Realization That Life Does Not Consist Either In

“The greatest gift is the realization that life does not consist either in wallowing in the past or peering anxiously into the future; and it is appalling to contemplate the great number of often painful steps by which ones arrives at a truth so old, so obvious, and so frequently expressed. It is good for one to appreciate that life is now. Whatever it offers, little or much, life is now –this day-this hour.” Charles Macomb Flandrau Ernest Hemingway drank here. Cuban revolutionaries Fidel Castro and Che Guevera drank here. A longhaired young hippie musician named Jimmy Buffett drank and performed here, too. From the 1930’s through today this rustic dive bar has seen more than its share of the famous and the infamous. It’s a little joint called Capt. Tony’s in Key West, Florida. Eighty-seven-year-old Anthony ‘Capt. Tony’ Tarracino has been the owner and proprietor of this boozy establishment since 1959. It seems Tony, as a young mobster, got himself into some serious trouble with ‘the family’ back in New Jersey and needed to lay low for a while. In those days, the mosquito invested ‘keys’ (or islands) on the southernmost end of Florida’s coastline was a fine place for wise guys on the lam to hide out. And this was well before the tee-shirt shops, restaurants, bars, art galleries, charming B&B’s and quaint hotels turned Key West into a serious year-round tourist destination. Sure, there were some ‘artsy’ types like Hemingway and Tennessee Williams living in Key West during the late 50’s when Tony bought the bar, but it was a seaside shanty town where muscular hard-working men in shrimp boats and cutters fished all day for a living. -

Thoughts on Rolling Stone Turning 50 - Men Behaving Badly, None So Much As America’S Top Soldiers

Counterculture Studies Volume 1 Issue 1 Article 7 2018 Thoughts on Rolling Stone turning 50 - Men behaving badly, none so much as America’s top soldiers Phillip Frazer [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ccs Recommended Citation Frazer, Phillip, Thoughts on Rolling Stone turning 50 - Men behaving badly, none so much as America’s top soldiers, Counterculture Studies, 1(1), 2018, 74-79. doi:10.14453/ccs.v1.i1.7 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Thoughts on Rolling Stone turning 50 - Men behaving badly, none so much as America’s top soldiers Abstract The following reminiscences and commentary by Phillip Frazer, original editor of the Australian edition of Rolling Stone, were first published during April 2017 in the Byron Echo and at dailyreview.com.au. In November of that year Joe Hagan’s The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine appeared in bookshops around the world. Wenner was the American founder and editor of the magazine. Since it was first published, the uninhibited biography has generated some controversy, initially due to a falling out between the biographer and his subject, but also in connection with the portrait of Wenner revealed therein. For example, one commentator noted upon reading the book: ‘All the sex, drugs & rock ‘n’ roll got a bit tiring after a while. Wenner may have been a "clever" businessman (to some extent) and got the right people on side, but despite his friendships with Springsteen and company, he was a rather despicable cad in many ways.’ Though Frazer met up with Wenner and had ongoing contact, the Australian edition of Rolling Stone appears to have been left to follow its own path, based around the American magazine’s successful template and the experience built up locally through Frazer’s experience with pop, rock and counterculture magazines such as GoSet (1965-73), Revolution (1970-1), High Times (1971-2) and The Digger (1972-5). -

[email protected] February 22, 2018 Mathew Rolston

Press Release For Immediate Release Contact: [email protected] February 22, 2018 Mathew Rolston, Hollywood Royale Out of the School of Los Angeles March 1 through April 21, 2018 Opening Reception Thursday, March 1, 7-9pm The Fahey/Klein Gallery is pleased to present Hollywood Royale: Out of the School of Los Angeles, the latest exhibition by noted Hollywood photographer Matthew Rolston. Rolston is an artist who works in photography and video; his practice centers on portraiture, most notably subjects drawn from celebrity culture. One of a handful of artists to emerge from Andy Warhol’s celebrity-focused Interview magazine, Rolston is a well-established icon of Hollywood photography. His latest exhibition and publication, Hollywood Royale: Out of the School of Los Angeles is a retrospective of his 1980s photography and presents a stunning array of portraits that beautifully capture the breadth of that decade’s iconic talent, from Michael Jackson to Madonna, from Cyndi Lauper to Prince. Alongside such luminaries as Herb Ritts and Greg Gorman, Rolston was a member of an influential group of photographers (among them, Bruce Weber, Annie Leibovitz, and Steven Meisel) who came from the 1980s magazine scene. Rolston helped define the era’s take on celebrity image-making, ‘gender bending,’ and much more. The photographs in this collection recall the glamour of old Hollywood with postmodern irony, helping to point the way towards the cult of fame with which we live today. Released in conjunction with this exhibition, Hollywood Royale: Out of the School of Los Angeles is also available as a lavish 262-page book, produced by teNeues and available for purchase through the gallery for $125. -

Music Magazines and Gendered Space: the Representation of Artists on the Covers of Hot Press and Rolling Stone

Irish Communication Review Volume 17 Issue 1 Article 5 July 2020 Music Magazines and Gendered Space: The Representation of Artists on the Covers of Hot Press and Rolling Stone Yvonne Kiely N/A, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Mass Communication Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kiely, Yvonne (2020) "Music Magazines and Gendered Space: The Representation of Artists on the Covers of Hot Press and Rolling Stone," Irish Communication Review: Vol. 17: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr/vol17/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Current Publications at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Irish Communication Review by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Music Magazines and Gendered Space: The Representation of Artists on the Covers of Hot Press and Rolling Stone Cover Page Footnote A special thank you to Denis Kiely, who made significant contributions ot the statistical analysis of this data. This article is available in Irish Communication Review: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr/vol17/iss1/5 Irish Communications Review vol 17 (2020) Music magazines and gendered space: The representation of artists on the covers of Hot Press and Rolling Stone Yvonne Kiely Abstract Over the past two decades the commercial music magazine industry has lapsed into a deepening cycle of continuous decline. -

Murdoch Empire Rocked Though the Murdoch Family Trust Controls Ed by Industry Insiders and Investors Alike

20110718-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 7/15/2011 8:25 PM Page 1 INSIDE REPORT TOP STORIES REAL ESTATE Picture this: Staten Hospitals Shift Spending Island is becoming Top Office Leases and Property Sales an artist magnet ® NEIGHBORHOODS, PAGE 12 PAGE 17-22 Barclays Center VOL. XXVII, NO. 29 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM JULY 18-24, 2011 PRICE: $3.00 makes play for profits PAGE 2 These new guests will create a buzz at the InterContinental PAGE 4 One way Walmart could enter NYC: Buy Rite Aid chain IN THE MARKETS, PAGE 4 WEALTH OF GREEN: Battery Park City is Are Jann Wenner’s flanked by riverfront mags for sale? parks full of playing kids, strollers and picnicking NEW YORK, NEW YORK, P. 6 families. THE NEW BUSINESS LIVES GOTHAM GIGS Salvaging hardwoods NEW DOWNTOWN from the wreckage P. 31 buck ennis ● ANNE FISHER Tech challenged? Help types who made up their social circle, the family is is on the way P. 31 Vibrant, sustainable, moving back to the neighborhood. Now a lively stretch filled with eclectic restaurants, Stone Street is Murdoch ● MOVERS & SHAKERS and family-friendly, transformed but no less appealing. Newmark’s Jeffrey Gural “I was blown away,”said Mr.Pasquarelli.“It defines is off to the races P. 32 lower Manhattan is the change downtown.” empire ● GAEL GREENE eats well From the eateries on Stone Street to the luxury res- at Grandma’s house P. 34 now an urban model idential buildings to the hotels to the towers rising at the World Trade Center site, signs of lower Manhat- rocked tan’s blossoming are unmistakable. -

Lifetime Achievement Award in the Nonperformer Category

LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD IN THE NONPERFORMER CATEGORY ■ SKS RS 1, Novem ber 9,1967 RS 68, October 15,1970 RS 81, A pril 29,1971 RS 191, July 17,1975 RS193, August 14,1975 RS 215, June 17,1976 RS 219, A ugust 12,1976 RS 248, September 22,1977 h ere a r e s o m e w h o sa y r o c k & r o ll, a t it s v e r y c o r e , writer for Rolling Stoneba.dk then was an early form of imbed is a temporary form. Even in the earliest days of ded journalism. David Felton would disappear for weeks into rock & roll, it was all folly, right? Passionate and the bizarre, baroque world of Brian Wilson in his sandbox cheeky melodies meant to be heard crackling over years. Robert Greenfield was invited to the South of France, a car radio, a souvenir of a night spent danring or where Keith Richards explained the savage dynamic between making out. Every real musician or fan knew, the Stones, the women they shared, his relationship with though, that rock & roll was much deeper than that. RockMick. & And Jann Wenner himself, in groundbreaking conver rollT was code, and just under the surface was the promise of re sations with Bob Dylan and in the spectacularly frank 1970 bellion, of a life beyond what your parents could post-Beatles interview with John Lennon, would understand. It was a secret world to smuggle into function as part literate fan, part therapist - your home, shut your door and get lost in. -

Reddick Public Library Locations at the Marion County Public Library System Noon- Lunch Where the Summer Break Spot Is Available

MARION COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY SYSTEM’S QUARTERLY NEWSMAGAZINE SUMMER 2018 | E 2 U ISS | 0 1 E M U L O V PLUS: ★ PROFILE ★ CALENDAR ★ BOOK REVIEW library.marioncountyfl.org words 1 wordsMarion County Public Library’s Quarterly Newsmagazine Volume 10 | Issue 2 | Summer 2018 a Marion County Public Library 2720 East Silver Springs Blvd. word Ocala, Florida 34470 352-368-4507 FROM THE email: [email protected] website: library.marioncountyfl.org DIRECTOR Library Director: Julie Sieg By Julie Sieg Director, Marion County NEWSMAGAZINE STAFF: Public Library System Publisher: The Friends of The Ocala Public Library Editor: Karen M. Jensen Library Community Liaison Salsa, Night Moves Writers: Erin Arnold, Jerome Azbell, and Kenny G Karen M. Jensen, Karen Kociemba, Music frames and memorializes moments in our life. Think about some Ben Hunter, of your most heart-felt memories and you’re likely to associate them to Marian Santiago, a particular song or musician. Think about happy times as a child, your Photos: Pat Lakin angst filled teenage years, your first love or broken heart, singing with your children, or hearing lyrics that really spoke to you when you needed it most. My entire life has been filled with music, from violin in elementary school, ON THE COVER: flute in middle and high school marching and concert band, community Celebrate summer at your public library. orchestra, theatre orchestra and minoring in music in college. Yet even being surrounded by music there are still musical memories that evoke such powerful emotions – a sense of happiness and well-being, nostalgia, and peace, love and contentment. -

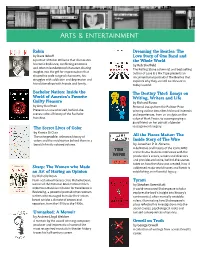

Arts & Entertainment

Arts & entertainment Robin Dreaming the Beatles: The by Dave Itzkoff Love Story of One Band and A portrait of Robin Williams that illuminates the Whole World his comic brilliance, conflicting emotions by Rob Sheffield and often misunderstood character, sharing The Rolling Stone columnist and best-selling insights into the gift orf improvisation that author of Love Is a Mix Tape presents an shaped his wide range of characters, his unconventional portrait of The Beatles that struggles with addiction and depression and explores why they are still so relevant in his relationships with friends and family. today's world. Bachelor Nation: Inside the The Destiny Thief: Essays on World of America's Favorite Writing, Writers and Life Guilty Pleasure by Richard Russo by Amy Kaufman Personal essays from the Pulitzer Prize- Presents an unauthorized, behind-the- winning author describes his broad interests scenes cultural history of the Bachelor and experiences, from an analysis on the franchise. value of Mark Twain, to accompanying a good friend on her pursuit of gender The Secret Lives of Color reassignment surgery. by Kassia St Clair The unforgettable, unknown history of All the Pieces Matter: The colors and the vivid stories behind them in a Inside Story of The Wire beautiful multi-colored volume. by Jonathan P. D. Abrams A definitive oral history of the iconic HBO crime drama features interviews with the production's actors, writers and directors and provides exclusive, behind-the-scenes takes on how the show was created, how it Sharp: The Women who Made addressed major world issues and how it is an Art of Having an Opinion establishing an influential legacy. -

Wenner, Jann (B

Wenner, Jann (b. 1946) by Craig Kaczorowski Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2006, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Jann Wenner, founder, publisher, and editor of the influential music and culture magazine Rolling Stone, is the editor in chief and chairman of Wenner Media, which also publishes the celebrity gossip magazine Us Weekly and the active lifestyle monthly Men's Journal. An emblematic baby boomer, Wenner is one of the founders of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and an ardent defender of free speech. In 1995, Wenner found himself in the middle of a media storm when it was revealed that he was leaving his wife Jane after more than 25 years of marriage and had become involved in a relationship with Matt Nye, a former male model turned fashion designer. Wenner's outing, which may or may not have been at his own instigation, seems to have had little effect on his business empire, but it inspired a number of accusations regarding an alleged "Velvet Mafia" of powerful closeted gay men. Early Life Born Jan S. Wenner in New York City on January 7, 1946, but raised in Marin County, California, he is the eldest of three children. His parents' marriage was not a happy one, and in 1958, while they were in the midst of an acrimonious divorce, the twelve-year-old Wenner was sent away to the Chadwick School (known, unofficially, as an "orphanage for rich kids") in the South Bay area of Los Angeles County. Wenner has asserted that neither parent ever visited him at Chadwick, and that a heated custody battle ensued because neither parent wanted him. -

Matthew Rolston Holds up a Funhouse Mirror to Art History

Matthew Rolston Holds Up a Funhouse Mirror to Art History In a striking new series, the storied magazine photographer revisits a curious popular reconstruction of some painterly and sculptural classics. by Michael Slenske When Matthew Rolston was growing up in LA's Hancock Park neighborhood he was a self-described "art school kid" who took painting and drawing classes at the Chouinard Art Institute and Art Center College of Design, where he later studied photography for two years before being discovered by Andy Warhol. His late brother Dean Rolston was the co-owner of the pioneering 56 Bleecker Gallery, and during school breaks Matthew flew to New York, slept on his brother's couch, and picked up the slack of Warhol's Studio 54 entourage. When Interview needed someone to shoot Steven Spielberg, Rolston got the assignment and Warhol became his first client. In the ensuing years, Rolston went on to shoot Michael Jackson's first cover for Interview magazine, and was soon enlisted by Jann Wenner to shoot U2's first Rolling Stone cover—eventually racking up more than a hundred of them over three decades. With a knack for theatrical lighting and teasing out unique color harmonies, Rolston became one of the most in-demand magazine photographers and music video directors (working with Madonna, Beyoncé, Lenny Kravitz, and Marilyn Manson) of the 1980s and ‘90s. "I'm not a theory person, I'm not an intellectual, I'm a visual artist, and after years of being at my clients' beck and call I'm going to take all the money I earned in the first half of my career and spend it in the second half doing exactly what I want to do," says Rolston, who has done just that over the past six years.