Chapter 2 Overview and Analysis of Decentralisation in the Three Countries Chapter 2 Overview and Analysis of Decentralisation in the Three Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bridging the “Pioneer Gap”: the Role of Accelerators in Launching High-Impact Enterprises

Bridging the “Pioneer Gap”: The Role of Accelerators in Launching High-Impact Enterprises A report by the Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs and Village Capital With the support of: Ross Baird Lily Bowles Saurabh Lall The Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) The Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) is a global network of organizations that propel entrepreneurship in emerging markets. ANDE members provide critical financial, educational, and busi- ness support services to small and growing businesses (SGBs) based on the conviction that SGBs will create jobs, stimulate long-term economic growth, and produce environmental and social benefits. Ultimately, we believe that SGBS can help lift countries out of poverty. ANDE is part of the Aspen Institute, an educational and policy studies organization. For more information please visit www.aspeninstitute.org/ande. Village Capital Village Capital sources, trains, and invests in impactful seed-stage enter- prises worldwide. Inspired by the “village bank” model in microfinance, Village Capital programs leverage the power of peer support to provide opportunity to entrepreneurs that change the world. Our investment pro- cess democratizes entrepreneurship by putting funding decisions into the hands of entrepreneurs themselves. Since 2009, Village Capital has served over 300 ventures on five continents building disruptive innovations in agriculture, education, energy, environmental sustainability, financial services, and health. For more information, please visit www.vilcap.com. Report released June 2013 Cover photo by TechnoServe Table of Contents Executive Summary I. Introduction II. Background a. Incubators and Accelerators in Traditional Business Sectors b. Incubators and Accelerators in the Impact Investing Sector III. Data and Methodology IV. -

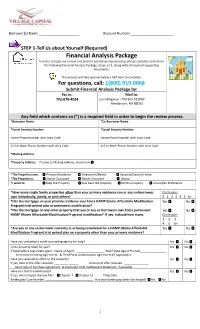

Financial Analysis Package in Order to Begin Our Review and Prevent Any Delays in Processing, Please Complete and Return

Borrower(s) Name Account Number STEP 1-Tell Us about Yourself (Required) Financial Analysis Package In order to begin our review and prevent any delays in processing, please complete and return the following Financial Analysis Package, Steps 1-11, along with all required supporting documents. This process will take approximately a half hour to complete. For questions, call: 1(800) 919-0068 Submit Financial Analysis Package by: Fax to: Mail to: 702-670-4024 Loss Mitigation – PO Box 531667 Henderson, NV 89053 Any field which contains an (*) is a required field in order to begin the review process. *Borrower Name *Co-Borrower Name *Social Security Number *Social Security Number Home Phone Number with Area Code Home Phone Number with Area Code Cell or Work Phone Number with Area Code Cell or Work Phone Number with Area Code *Mailing Address *Property Address If same as Mailing Address, check here *The Property is my: Primary Residence Investment/Rental Seasonal/Second Home *The Property is: Owner Occupied Renter Occupied Vacant *I want to: Keep the Property Give back the property Sell the property Unsure/No Preference *How many single family properties other than your primary residence you or any co-borrowers Circle one: own individually, jointly, or with others? 0 1 2 3 4 5 6+ *Has the mortgage on your primary residence ever had a HAMP (Home Affordable Modification Yes No Program) trial period plan or permanent modification? *Has the mortgage on any other property that you or any co-borrowers own had a permanent Yes No HAMP (Home Affordable Modification Program) modification? If yes, indicate how many. -

Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa

sustainability Article Between Village and Town: Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa Jytte Agergaard * , Susanne Kirkegaard and Torben Birch-Thomsen Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, University of Copenhagen, Oster Voldgade 13, DK-1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark; [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (T.B.-T.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In the next twenty years, urban populations in Africa are expected to double, while urban land cover could triple. An often-overlooked dimension of this urban transformation is the growth of small towns and medium-sized cities. In this paper, we explore the ways in which small towns are straddling rural and urban life, and consider how insights into this in-betweenness can contribute to our understanding of Africa’s urban transformation. In particular, we examine the ways in which urbanism is produced and expressed in places where urban living is emerging but the administrative label for such locations is still ‘village’. For this purpose, we draw on case-study material from two small towns in Tanzania, comprising both qualitative and quantitative data, including analyses of photographs and maps collected in 2010–2018. First, we explore the dwindling role of agriculture and the importance of farming, businesses and services for the diversification of livelihoods. However, income diversification varies substantially among population groups, depending on economic and migrant status, gender, and age. Second, we show the ways in which institutions, buildings, and transport infrastructure display the material dimensions of urbanism, and how urbanism is planned and aspired to. Third, we describe how well-established middle-aged households, independent women (some of whom are mothers), and young people, mostly living in single-person households, explain their visions and values of the ways in which urbanism is expressed in small towns. -

Village Officers Handbook

OHIO VILLAGE OFFICER’S HANDBOOK ____________________________________ March 2017 Dear Village Official: Public service is both an honor and challenge. In the current environment, service at the local level may be more challenging than ever before. This handbook is one small way my office seeks to assist you in meeting that challenge. To that end, this handbook is designed to be updated easily to ensure you have the latest information at your fingertips. Please feel free to forward questions, concerns or suggestions to my office so that the information we provide is accurate, timely and relevant. Of course, a manual of this nature is not to be confused with legal advice. Should you have concerns or questions of a legal nature, please consult your statutory legal counsel, the county prosecutor’s office or your private legal counsel, as appropriate. I understand the importance of local government and want to make sure we are serving you in ways that meet your needs and further our shared goals. If my office can be of further assistance, please let us know. I look forward to working with you as we face the unique challenges before us and deliver on our promises to the great citizens of Ohio. Thank you for your service. Sincerely, Dave Yost Auditor of State 88 East Broad Street, Fifth Floor, Columbus, Ohio 43215-3506 Phone: 614-466-4514 or 800-282-0370 Fax: 614-466-4490 www.ohioauditor.gov This page is intentionally left blank. Village Officer’s Handbook TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Home Rule I. Definition ............................................................................................................................ 1-1 II. -

Social Sustainability and Redevelopment of Urban Villages in China: a Case Study of Guangzhou

sustainability Case Report Social Sustainability and Redevelopment of Urban Villages in China: A Case Study of Guangzhou Fan Wu 1, Ling-Hin Li 2,* ID and Sue Yurim Han 2 1 Department of Construction Management, School of Civil Engineering and Transportation, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou 510630, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Real Estate and Construction, Faculty of Architecture, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +852-2859-2128 Received: 21 May 2018; Accepted: 19 June 2018; Published: 21 June 2018 Abstract: Rapid economic development in China has generated substantial demand for urban land for development, resulting in an unprecedented urbanization process. The expansion of urbanized cities has started to engulf rural areas, making the urban–rural boundary less and less conspicuous in China. Urban encroachment has led to a rapid shrinkage of the rural territory as the rural–urban migration has increased due to better job opportunities and living standards in the urban cities. Urban villages, governed by a rural property rights mechanism, have started to emerge sporadically within urbanised areas. Various approaches, such as state-led, developer-led, or collective-led approaches, to redevelop these urban villages have been adopted with varying degrees of success. This paper uses a case-study framework to analyse the state–market interplay in two very different urban village redevelopment cases in Guangzhou. By an in-depth comparative analysis of the two regeneration cases in Guangzhou, which started within close proximity in terms of geographical location and timing, we are able to shed light on how completely different outcomes may result from different forms of state–market interplay. -

The Shifting of Village Autonomy Concept in Indonesia

THE SHIFTING OF VILLAGE AUTONOMY CONCEPT IN INDONESIA Abstract This research tries to examine comprehensively about the different concepts about village autonomy in Law No. 5 of 1979 and Law No. 6 of 2014. The results supposed to be contributed as scientific journal and other scientific work, which is valuable for scientific improvement in provincial autonomy law. Itsurely could be used by the local governments in Indonesia and hopefully in Asia as a framework to construct a strategic procedure of the village development. This study uses the conceptual approach and analysis approach as methods. The conceptual approach directed to examine the first legal issue related to differ autonomy concept in Law No. 5 of 1979 and Law No. 6 of 2014 while the analytical approach is used for assessing the alignment of the concept of village autonomy in Law No. 6 of 2014 with a constitutional mandate. The results found, there is improvements in the draft of Law No. 6 Year 2014 by increasing the funding source for the village, and guarantee the right to determine her village. A village, in Law No. 6 Year 2014, is possible to switch into a custom village. Keywords: village, village governance, village autonomy I. Introduction Enactment of the Law No. 6 Year 2014, constantly ended the village government setting in Law No. 32 Year 2004,1and a sign of the village model setting within a different law. Such condition had ever occurred in the New Order era by the emerging of Law No. 5 Year 1979 on Village (“Village Law”). This concept of Village Government may cause a lot of problems such as weakening the capacity of the village administration, policy form and the village unique 2. -

The Castle and the Village: the Many Faces of Limited Access

01-7501-1 CH 1 10/28/08 5:17 PM Page 3 1 The Castle and the Village: The Many Faces of Limited Access jorrit de jong and gowher rizvi Access Denied No author in world literature has done more to give shape to the nightmarish challenges posed to access by modern bureaucracies than Franz Kafka. In his novel The Castle, “K.,” a land surveyor, arrives in a village ruled by a castle on a hill (see Kafka 1998). He is under the impression that he is to report for duty to a castle authority. As a result of a bureaucratic mix-up in communications between the cas- tle officials and the villagers, K. is stuck in the village at the foot of the hill and fails to gain access to the authorities. The villagers, who hold the castle officials in high regard, elaborately justify the rules and procedures to K. The more K. learns about the castle, its officials, and the way they relate to the village and its inhabitants, the less he understands his own position. The Byzantine codes and formalities gov- erning the exchanges between castle and village seem to have only one purpose: to exclude K. from the castle. Not only is there no way for him to reach the castle, but there is also no way for him to leave the village. The villagers tolerate him, but his tireless struggle to clarify his place there only emphasizes his quasi-legal status. Given K.’s belief that he had been summoned for an assignment by the authorities, he remains convinced that he has not only a right but also a duty to go to the cas- tle! How can a bureaucracy operate in direct opposition to its own stated pur- poses? How can a rule-driven institution be so unaccountable? And how can the “obedient subordinates” in the village wield so much power to act in their own self- 3 01-7501-1 CH 1 10/28/08 5:17 PM Page 4 4 jorrit de jong and gowher rizvi interest? But because everyone seems to find the castle bureaucracy flawless, it is K. -

Is It Time for New York State to Revise Its Village Incorporation Laws? a Background Report on Village Incorporation in New York State

Is It Time For New York State to Revise Its Village Incorporation Laws? A Background Report on Village Incorporation in New York State Lisa K. Parshall January 2020 1 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Lisa Parshall is a professor of political science at Daemen College in Amherst, New York and a public Photo credit:: Martin J. Anisman policy fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government 2 Is It Time for New York State to Revise Its Village Incorporation Laws? Over the past several years, New York State has taken considerable steps to eliminate or reduce the number of local governments — streamlining the law to make it easier for citizens to undertake the process as well as providing financial incentives for communities that undertake consolidations and shared services. Since 2010, the residents of 42 villages have voted on the question of whether to dissolve their village government. This average of 4.7 dissolution votes per year is an increase over the .79 a-year-average in the years 1972-2010.1 The growing number of villages considering dissolution is attributable to the combined influence of declining populations, growing property tax burdens, and the passage of the New N.Y. Government Reorganization and Citizen Empowerment Act (herein after the Empowerment Act), effective in March 2019, which revised procedures to make it easier for citizens to place dissolution and consolidation on the ballot. While the number of communities considering and voting on dissolution has increased, the rate at which dissolutions have been approved by the voters has declined. That is, 60 percent of proposed village dissolutions bought under the provisions of the Empowerment Act have been rejected at referendum (see Dissolving Village Government in New York State: A Symbol of a Community in Decline or Government Modernization?)2 While the Empowerment Act revised the processes for citizen-initiated dissolutions and consolidations, it left the provisions for the incorporation of new villages unchanged. -

Sustaining the Village Movement

SUSTAINING THE VILLAGE MOVEMENT LESSONS FROM PIONEERS about Village Business Models and Sustainability CAPITAL IMPACT PARTNERS This report is sponsored by Capital Impact Partners 2015 About Capital Impact Partners Capital Impact Partners is a Hill Village, developed and leader in financial and social managed the national Village innovation for communities. to Village (VtV) Network. This A non-profit community national peer to peer learning development -financial network allows communities institution, Capital Impact interested in starting and brings together roots in sustaining Villages to share cooperative development, a knowledge and access expert diverse network of partners technical assistance through and problem-solving know- a web based portal. From how to connect communities 2011-2014, Capital Impact to capital and capabilities that Partners, as part of Archstone together create social change. Foundation’s Creating Age- Capital Impact Partners Friendly Communities through became involved in the the Expansion of Villages Village movement because Initiative, provided capacity it resonated so strongly with building to strengthen the organization’s focus on the business acumen and community empowerment and sustainability of nine its commitment to respectful Villages in California. and dignified aging for older For more information on adults. From 2009-2014, Capital Impact Partners visit Capital Impact Partners, in www.capitalimpact.org partnership with Beacon Acknowledgements: Capital Impact Partners would like to acknowledge Candace Baldwin, Janis Brewer and Judy Willett for their expertise, energy and diligence as authors of this report. Thank you to Jason Bell’s Creative and Dean Creative who helped bring this report to life. A special thank you to the Villages who provided their knowledge and experience as early pioneers of the Village movement to help shape the information shared in this report. -

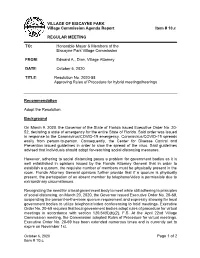

Page 1 of 2 Item # 10.C VILLAGE of BISCAYNE PARK Village Commission Agenda Report Item # 10.C REGULAR MEETING TO: Honorable

VILLAGE OF BISCAYNE PARK Village Commission Agenda Report Item # 10.c REGULAR MEETING TO: Honorable Mayor & Members of the Biscayne Park Village Commission FROM: Edward A., Dion, Village Attorney DATE: October 6, 2020 TITLE: Resolution No. 2020-58 Approving Rules of Procedure for hybrid meetings/hearings Recommendation Adopt the Resolution. Background On March 9, 2020, the Governor of the State of Florida issued Executive Order No. 20- 52, declaring a state of emergency for the entire State of Florida. Said order was issued in response to the Coronavirus/COVID-19 emergency. Coronavirus/COVID-19 spreads easily from person-to-person. Consequently, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention issued guidelines in order to slow the spread of the virus. Said guidelines advised that individuals should adopt far-reaching social distancing measures. However, adhering to social distancing poses a problem for government bodies as it is well established in opinions issued by the Florida Attorney General that in order to establish a quorum, the requisite number of members must be physically present in the room. Florida Attorney General opinions further provide that if a quorum is physically present, the participation of an absent member by telephone/video is permissible due to extraordinary circumstances. Recognizing the need for a local government body to meet while still adhering to principles of social distancing, on March 20, 2020, the Governor issued Executive Order No. 20-69, suspending the present-in-the-room quorum requirement and expressly allowing for local government bodies to utilize telephonic/video conferencing to hold meetings. Executive Order No. 20-69 requires that local government bodies adopt rules of procedure for virtual meetings in accordance with section 120.54(5)(b)(2), F.S. -

Town of New Canaan Village District Design Guidelines EFFECTIVE

Town of New Canaan Village District Design Guidelines TH EFFECTIVE JUNE 30 2010 Design Guidelines – Town of New Canaan Table of Contents 1.0 ARCHITECTURAL CHARACTER .................................................................................... 2 2.0 HEIGHT, BULK AND SCALE COMPATIBILITY ............................................................... 5 3.0 SITE PLANNING FOR A HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT ..................................................... 6 4.0 SITE PLANNING FOR A PEDESTRIAN ENVIRONMENT ............................................... 7 5.0 ENVIRONMENTAL / SUSTAINABLE DESIGN STANDARDS ......................................... 8 5.1 BUILDING DESIGN ........................................................................................................................ 8 5.2 SITE DESIGN ................................................................................................................................. 9 6.0 NEW CANAAN VILLAGE DISTRICT ELEMENTS OF DESIGN ....................................... 9 6.1 ARCHITECTUAL DESIGN ............................................................................................................ 10 6.1.1 Façade Articulation ........................................................................................................ 10 6.1.2 Architectural Concept and Consistency ......................................................................... 11 6.1.3 Architectural Cues ......................................................................................................... 13 6.1.4 -

Village District Concept Powerpoint

Village District Conceptfor West Haven Center West Haven Planning and Zoning Commission June 2019 What is a Village District? State law allows municipalities to establish village districts and local historic districts, and either approach can be used to promote economic development and protect community character. A municipality can simultaneously use both approaches, and at least one municipality is doing so. Both involve greater local control over the design and construction, or rehabilitation of buildings. But they operate differently and they vary with respect to the steps a municipality must follow to create them. Plan of Conservation And Development Adopted June 2017 Plan of Conservation and Development Plan of Conservation and Development Plan of Conservation and Development What Other Communities have Village Districts? •Town of Branford •Town of Clinton •Town of Hamden (Spring Glen) •City of Middletown •City of Stamford (Glendale, Spring Glen) •Town of Westport (Center District) What Does it Mean forProperty Owners? • P&Z already regulates uses of property in this area. • New Regulation would assure that visible changes would be subject to additional architectural review by area professional architects. • Why? To protect the character and guide new development of WestHaven Center. This is NOT the Same as a Historic District HISTORIC DISTRICT VILLAGE DISTRICT •Requires a lengthy study process, an •Can be adopted directly by a vote of the affirmative vote by the property Planning and Zoning Commission. owners, and approval by the town. •Reviews are conducted by a consultant •Local Historic District reviews are or architectural review board who usually conducted by the members of submits a report and recommendations the district commission.