Outdated Municipal Structures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operating Budget &

ADOPTED FY 2009/10 OPERATING BUDGET & Capital Improvement Program ANAHEIM, CALIFORNIA FY 2009/10 Adopted Budget City of Anaheim, California Fiscal Year (FY) 2009/10 Adopted Budget FY 2009/10 - FY 2013/14 Adopted Capital Improvement Program Curt Pringle, Mayor Robert Hernandez, Mayor Pro Tem Lorri Galloway, Council Member Lucille Kring, Council Member Harry S. Sidhu, P.E., Council Member Thomas J. Wood, City Manager Marcie L. Edwards, Assistant City Manager Prepared by the Department of Finance William G. Sweeney, Finance Director City of Anaheim, California City of Anaheim, California i FY 2009/10 Adopted Budget The Government Finance Officers Association of the United States and Canada (GFOA) presented a Distinguished Budget Presentation Award to the City of Anaheim, California for its annual budget for the fiscal period beginning July 1, 2008. In order to receive this award, a government unit must publish a budget document that meets program criteria as a policy document, as an operations guide, as a financial plan, and as a communications device. This award is valid for a period of one year only. We believe our current budget continues to conform to program requirements and we are submitting it to GFOA for award consideration. FY 2009/10 Adopted Budget ii City of Anaheim, California TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary City Manager’s Transmittal Letter . .1 City of Anaheim Organizational Chart. 3 Directory of Officials . 4 Executive Summary . 6 City Profile . 15 City Financial Information . 18 Financial Management Policies . 20 Full-Time Position Comparison . 23 Summary of Full-Time Position Adjustments. 25 Fund Summaries A Look at the Budget by Fund . -

City of South Lake Tahoe Municipal Services Review and Sphere of Influence Update

Agenda Item #4E Page 1 of 99 PUBLIC REVIEW DRAFT EL DORADO LOCAL AGENCY FORMATION COMMISSION (LAFCO) CITY OF SOUTH LAKE TAHOE MUNICIPAL SERVICES REVIEW AND SPHERE OF INFLUENCE UPDATE MAY 2016 Agenda Item #4E Page 2 of 99 PUBLIC REVIEW DRAFT CITY OF SOUTH LAKE TAHOE MUNICIPAL SERVICES REVIEW AND SPHERE OF INFLUENCE UPDATE Prepared for: El Dorado Local Agency Formation Commission 550 Main Street Placerville, CA 95667 Contact Person: Jose Henriquez, Executive Officer Phone: (530) 295-2707 Consultant: 6051 N. Fresno Street, Suite 200 Contact: Steve Brandt, Project Manager Phone: (559) 733-0440 Fax: (559) 733-7821 May 2016 © Copyright by Quad Knopf, Inc. Unauthorized use prohibited. Cover Photo: City of South Lake Tahoe 150245 Agenda Item #4E Page 3 of 99 EL DORADO LOCAL AGENCY FORMATION COMMISSION Commissioners Shiva Frentzen, El Dorado County Representative Brian Veerkamp, El Dorado County Representative Mark Acuna, City Representative Austin Sass, City Representative Dale Coco, MD, Special District Representative Ken Humphreys, Chair, Special District Representative Dyana Anderly, Public Member Representative Alternate Commissioners John Clerici, City Representative Niles Fleege, Public Member Representative Holly Morrison, Special District Representative Michael Ranalli, El Dorado County Representative Staff Jose Henriquez, Executive Officer Erica Sanchez, Policy Analyst Denise Tebaldi, Interim Commission Clerk Legal Counsel Kara Ueda, LAFCO Counsel Consultant 6051 N. Fresno, Suite 200 Fresno, CA 93710 Copyright by Quad Knopf, Inc. Unauthorized use prohibited. © 150245 Agenda Item #4E Page 4 of 99 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1 - Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 - Role and Responsibility of Local Agency Formation Commission (LAFCo) ...... 1-1 1.2 - Municipal Service Review Purpose ................................................................................... -

Bridging the “Pioneer Gap”: the Role of Accelerators in Launching High-Impact Enterprises

Bridging the “Pioneer Gap”: The Role of Accelerators in Launching High-Impact Enterprises A report by the Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs and Village Capital With the support of: Ross Baird Lily Bowles Saurabh Lall The Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) The Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) is a global network of organizations that propel entrepreneurship in emerging markets. ANDE members provide critical financial, educational, and busi- ness support services to small and growing businesses (SGBs) based on the conviction that SGBs will create jobs, stimulate long-term economic growth, and produce environmental and social benefits. Ultimately, we believe that SGBS can help lift countries out of poverty. ANDE is part of the Aspen Institute, an educational and policy studies organization. For more information please visit www.aspeninstitute.org/ande. Village Capital Village Capital sources, trains, and invests in impactful seed-stage enter- prises worldwide. Inspired by the “village bank” model in microfinance, Village Capital programs leverage the power of peer support to provide opportunity to entrepreneurs that change the world. Our investment pro- cess democratizes entrepreneurship by putting funding decisions into the hands of entrepreneurs themselves. Since 2009, Village Capital has served over 300 ventures on five continents building disruptive innovations in agriculture, education, energy, environmental sustainability, financial services, and health. For more information, please visit www.vilcap.com. Report released June 2013 Cover photo by TechnoServe Table of Contents Executive Summary I. Introduction II. Background a. Incubators and Accelerators in Traditional Business Sectors b. Incubators and Accelerators in the Impact Investing Sector III. Data and Methodology IV. -

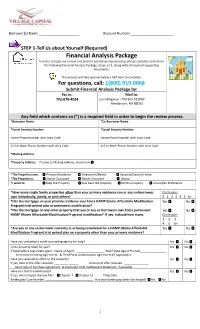

Financial Analysis Package in Order to Begin Our Review and Prevent Any Delays in Processing, Please Complete and Return

Borrower(s) Name Account Number STEP 1-Tell Us about Yourself (Required) Financial Analysis Package In order to begin our review and prevent any delays in processing, please complete and return the following Financial Analysis Package, Steps 1-11, along with all required supporting documents. This process will take approximately a half hour to complete. For questions, call: 1(800) 919-0068 Submit Financial Analysis Package by: Fax to: Mail to: 702-670-4024 Loss Mitigation – PO Box 531667 Henderson, NV 89053 Any field which contains an (*) is a required field in order to begin the review process. *Borrower Name *Co-Borrower Name *Social Security Number *Social Security Number Home Phone Number with Area Code Home Phone Number with Area Code Cell or Work Phone Number with Area Code Cell or Work Phone Number with Area Code *Mailing Address *Property Address If same as Mailing Address, check here *The Property is my: Primary Residence Investment/Rental Seasonal/Second Home *The Property is: Owner Occupied Renter Occupied Vacant *I want to: Keep the Property Give back the property Sell the property Unsure/No Preference *How many single family properties other than your primary residence you or any co-borrowers Circle one: own individually, jointly, or with others? 0 1 2 3 4 5 6+ *Has the mortgage on your primary residence ever had a HAMP (Home Affordable Modification Yes No Program) trial period plan or permanent modification? *Has the mortgage on any other property that you or any co-borrowers own had a permanent Yes No HAMP (Home Affordable Modification Program) modification? If yes, indicate how many. -

Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa

sustainability Article Between Village and Town: Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa Jytte Agergaard * , Susanne Kirkegaard and Torben Birch-Thomsen Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, University of Copenhagen, Oster Voldgade 13, DK-1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark; [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (T.B.-T.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In the next twenty years, urban populations in Africa are expected to double, while urban land cover could triple. An often-overlooked dimension of this urban transformation is the growth of small towns and medium-sized cities. In this paper, we explore the ways in which small towns are straddling rural and urban life, and consider how insights into this in-betweenness can contribute to our understanding of Africa’s urban transformation. In particular, we examine the ways in which urbanism is produced and expressed in places where urban living is emerging but the administrative label for such locations is still ‘village’. For this purpose, we draw on case-study material from two small towns in Tanzania, comprising both qualitative and quantitative data, including analyses of photographs and maps collected in 2010–2018. First, we explore the dwindling role of agriculture and the importance of farming, businesses and services for the diversification of livelihoods. However, income diversification varies substantially among population groups, depending on economic and migrant status, gender, and age. Second, we show the ways in which institutions, buildings, and transport infrastructure display the material dimensions of urbanism, and how urbanism is planned and aspired to. Third, we describe how well-established middle-aged households, independent women (some of whom are mothers), and young people, mostly living in single-person households, explain their visions and values of the ways in which urbanism is expressed in small towns. -

Village Officers Handbook

OHIO VILLAGE OFFICER’S HANDBOOK ____________________________________ March 2017 Dear Village Official: Public service is both an honor and challenge. In the current environment, service at the local level may be more challenging than ever before. This handbook is one small way my office seeks to assist you in meeting that challenge. To that end, this handbook is designed to be updated easily to ensure you have the latest information at your fingertips. Please feel free to forward questions, concerns or suggestions to my office so that the information we provide is accurate, timely and relevant. Of course, a manual of this nature is not to be confused with legal advice. Should you have concerns or questions of a legal nature, please consult your statutory legal counsel, the county prosecutor’s office or your private legal counsel, as appropriate. I understand the importance of local government and want to make sure we are serving you in ways that meet your needs and further our shared goals. If my office can be of further assistance, please let us know. I look forward to working with you as we face the unique challenges before us and deliver on our promises to the great citizens of Ohio. Thank you for your service. Sincerely, Dave Yost Auditor of State 88 East Broad Street, Fifth Floor, Columbus, Ohio 43215-3506 Phone: 614-466-4514 or 800-282-0370 Fax: 614-466-4490 www.ohioauditor.gov This page is intentionally left blank. Village Officer’s Handbook TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Home Rule I. Definition ............................................................................................................................ 1-1 II. -

Social Sustainability and Redevelopment of Urban Villages in China: a Case Study of Guangzhou

sustainability Case Report Social Sustainability and Redevelopment of Urban Villages in China: A Case Study of Guangzhou Fan Wu 1, Ling-Hin Li 2,* ID and Sue Yurim Han 2 1 Department of Construction Management, School of Civil Engineering and Transportation, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou 510630, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Real Estate and Construction, Faculty of Architecture, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +852-2859-2128 Received: 21 May 2018; Accepted: 19 June 2018; Published: 21 June 2018 Abstract: Rapid economic development in China has generated substantial demand for urban land for development, resulting in an unprecedented urbanization process. The expansion of urbanized cities has started to engulf rural areas, making the urban–rural boundary less and less conspicuous in China. Urban encroachment has led to a rapid shrinkage of the rural territory as the rural–urban migration has increased due to better job opportunities and living standards in the urban cities. Urban villages, governed by a rural property rights mechanism, have started to emerge sporadically within urbanised areas. Various approaches, such as state-led, developer-led, or collective-led approaches, to redevelop these urban villages have been adopted with varying degrees of success. This paper uses a case-study framework to analyse the state–market interplay in two very different urban village redevelopment cases in Guangzhou. By an in-depth comparative analysis of the two regeneration cases in Guangzhou, which started within close proximity in terms of geographical location and timing, we are able to shed light on how completely different outcomes may result from different forms of state–market interplay. -

Anneke Jans' Maternal Grandfather and Great Grandfather

Anneke Jans’ Maternal Grandfather and Great Grandfather By RICIGS member, Gene Eiklor I have been writing a book about my father’s ancestors. Anneke Jans is my 10th Great Grandmother, the “Matriarch of New Amsterdam.” I am including part of her story as an Appendix to my book. If it proves out, Anneke Jans would be the granddaughter of Willem I “The Silent” who started the process of making the Netherlands into a republic. Since the records and info about Willem I are in the hands of the royals and government (the Royals are buried at Delft under the tomb of Willem I) I took it upon myself to send the Appendix to Leiden University at Leiden. Leiden University was started by Willem I. An interesting fact is that descendants of Anneke have initiated a number of unsuccessful attempts to recapture Anneke’s land on which Trinity Church in New York is located. In Chapter 2 – Dutch Settlement, page 29, Anneke Jans’ mother was listed as Tryntje (Catherine) Jonas. Each were identified as my father’s ninth and tenth Great Grandmothers, respectively. Since completion of that and succeeding chapters I learned from material shared by cousin Betty Jean Leatherwood that Tryntje’s husband had been identified. From this there is a tentative identification of Anneke’s Grandfather and Great Grandfather. The analysis, the compilation and the writings on these finds were done by John Reynolds Totten. They were reported in The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Volume LVI, No. 3, July 1925i and Volume LVII, No. 1, January 1926ii Anneke is often named as the Matriarch of New Amsterdam. -

Is It Time for New York State to Revise Its Village Incorporation Laws? a Background Report on Village Incorporation in New York State

Is It Time For New York State to Revise Its Village Incorporation Laws? A Background Report on Village Incorporation in New York State Lisa K. Parshall January 2020 1 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Lisa Parshall is a professor of political science at Daemen College in Amherst, New York and a public Photo credit:: Martin J. Anisman policy fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government 2 Is It Time for New York State to Revise Its Village Incorporation Laws? Over the past several years, New York State has taken considerable steps to eliminate or reduce the number of local governments — streamlining the law to make it easier for citizens to undertake the process as well as providing financial incentives for communities that undertake consolidations and shared services. Since 2010, the residents of 42 villages have voted on the question of whether to dissolve their village government. This average of 4.7 dissolution votes per year is an increase over the .79 a-year-average in the years 1972-2010.1 The growing number of villages considering dissolution is attributable to the combined influence of declining populations, growing property tax burdens, and the passage of the New N.Y. Government Reorganization and Citizen Empowerment Act (herein after the Empowerment Act), effective in March 2019, which revised procedures to make it easier for citizens to place dissolution and consolidation on the ballot. While the number of communities considering and voting on dissolution has increased, the rate at which dissolutions have been approved by the voters has declined. That is, 60 percent of proposed village dissolutions bought under the provisions of the Empowerment Act have been rejected at referendum (see Dissolving Village Government in New York State: A Symbol of a Community in Decline or Government Modernization?)2 While the Empowerment Act revised the processes for citizen-initiated dissolutions and consolidations, it left the provisions for the incorporation of new villages unchanged. -

Shelby Village

ORDINANCE NO. 20200413-1 VILLAGE OF SHELBY COUNTY OF OCEANA STATE OF MICHIGAN THE VILLAGE OF SHELBY HEREBY ORDAINS: SHORT TITLE: ORV ORDINANCE AN ORDINANCE AUTHORIZING AND REGULATING THE OPERATION OF OFF-ROAD VEHICLES {ORVs) ON VILLAGE MAJOR STREETS AND VILLAGE LOCAL STREETS IN SHELBY VILLAGE, OCEANA COUNTY, MICHIGAN, PROVIDING PENALTIES FOR THE VIOLATION THEREOF, AND FOR THE DISTRIBUTION OF FINES AND COSTS RESULTING FROM THOSE PENALTIES PURSUANT TO 2009 PA 175, MCL 324.81131. Section 1. Definitions. For the purpose of this Ordinance, the following definitions shall apply unless the context clearly indicates or requires a different meaning: a. County means Oceana County, Michigan. b. Direct Supervision, means the direct visual observation of the operator with the unaided or normally correct eye, where the observer is able to come to the immediate aid of the operator. c. Driver's License means any driving privileges, license, temporary instruction permit or temporary license issued under the laws of any state, territory or possession of the United States, Indian country as defined in 18 USC 1151, the District of Columbia, and the Dominion of Canada pertaining to the licensing of persons to operate motor vehicles. d. Maintained Portion means that portion of road, improved, designated, and/or ordinarily used for vehicular traffic, including the gravel shoulder or paved shoulder of the road. e. Operate, means to ride in or on and be in actual physical control of the operation of an ORV/ATV. f. Operator means a person who operates or is in actual physical control of the operation of an ORV/ATV. -

2020 Illinois City/County Management Association Officers and Board Of

2019- 2020 Illinois City/County Management Association Officers and Board of Directors President Ray Rummel Village Manager, Elk Grove Village 901 Wellington Avenue Board Brad Burke Elk Grove Village, IL 60007 Member Village Manager, Lincolnshire Email: [email protected] Metro One Olde Half Day Road Phone: 847-357-4010 Lincolnshire, IL 60069 Email: [email protected] President-Elect Ken Terrinoni Phone: 847-913-2335 County Administrator, Boone County 1212 Logan Avenue Board Hadley Skeffington Vox Belvidere, IL 61008 Member Deputy Village Manager, Niles Email: [email protected] IAMMA 1000 Civic Center Drive Phone: 815-547-4770 Niles, IL 60714 Email: [email protected] Vice President Drew Irvin Phone: 847-588-8009 Village Manager, Lake Bluff 40 East Center Avenue Board Darin Girdler Lake Bluff, IL 60044 Member MIT Downstate Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Phone: 847-283-6883 Phone: 618-971-8276 Secretary/ Dorothy David Board Scott Hartman Treasurer City Manager, Champaign Member Deputy County Administrator, McHenry 102 North Neil Street County Champaign, IL 61820 IACA 2200 N. Seminary Ave. Email: [email protected] McHenry, IL 60098 Phone: 217-403-8710 Email: [email protected] Phone: 815-334-4924 Immediate Mike Cassady Past President Village Manager, Mount Prospect Board Grant Litteken 50 South Emerson Member Assistant City Administrator, O’Fallon Mt. Prospect, IL 60056 SWICMA 255 S. Lincoln Ave Email: [email protected] Trenton, IL 62269 Phone: 847-818-5401 Email: [email protected] Phone: 618-624-4500 Board Randy Bukas Member Accounting Supervisor/City Treasurer Board Kimberly Richardson expires: 6-30-20 314 W. -

Some Totem Poles Around Juneau Can You Find These Poles? Check Them Off When You’Ve Seen Them! Downtown

Some Totem Poles around Juneau Can you find these poles? Check them off when you’ve seen them! Downtown Four Story Totem Location: Outside Juneau-Douglas City Museum, Fourth and Main Streets Carver: Haida carver John Wallace of Hydaburg, 1940. Harnessing the Atom Totem Location: Outside Juneau-Douglas City Museum, Calhoun and Main Streets Carver: Tlingit master carver Amos Wallace of Juneau, 1967, installed 1976 The Wasgo Totem Pole or Old Witch Totem Location: State Office Building, Main lobby, Eighth Floor, Fourth and Calhoun Streets Carver: Haida carver Dwight Wallace, 1880, installed 1977 Friendship Totem Location: Juneau Courthouse Lobby, on Fourth Street between Main and Seward Carver: Tlingit carver Leo Jacobs of Haines, in association with carvers from the Alaska Indian Arts Inc. of Port Chilkoot, mid-1960s. The Family Location: Capital School Playground, Seward and 6th Streets Carver: Tlingit artist Michael L. Beasley, 1996 Box of Daylight and Eagle/Bear Totems Location: Sealaska Corp. Building, One Sealaska Plaza Carver: Box of Daylight: Tlingit carvers Nathan Jackson and Steven Brown, 1984. Eagle/ Bear: Haida artist Warren Peele,1984. Raven and Tl'anax'eet'ák'w (Wealth Bringer) Totem Location; Mount Roberts Tramway, 490 S. Franklin St. Carver: Tlingit carver Stephen Jackson of Ketchikan, raised in 2000 Aak'w Tribe Totem Location: Juneau Douglas High School commons, 1639 Glacier Ave. Carver: Tlingit carver Nathan Jackson, with the assistance of Steven C. Brown, 1980-81 Legends and Beliefs, Creation of Killer Whale and Strongman Totems Location: Goldbelt Place, 801 10th St. Carvers: Tlingit carvers Ray Peck and Jim Marks, 1981 Raven and Eagle Totem Location: Federal building lobby, 709 W.