Universi^ International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Educational Performances

2017 EDUCATIONAL PERFORMANCES A Production of the Pennsylvania Renaissance Faire Inside the imposing Mount Hope Mansion, visitors enter the world of Edgar Allan Poe, experiencing his tales recounted by those who have lived the stories, spinning tales of mystery, horror and suspense that guests to the Mansion will long remember. 2017 Theme Stories, and Poems— In this, the year of our Lord 1848, we here at Mount Hope Penitentiary are proud to be at the very forefront of the modern wave of prison reform and criminal rehabilitation. We pride ourselves on taking the worst, most horribly depraved felons of our age, and through a number of revolutionary techniques, reconditioning them to be mild, submissive, truly penitent individuals. For a very limited time, Mrs. Evangeline Mallard, President of the Prison Board of Inspectors, invites you to join us at Mount Hope for a demonstration of rehabilitation through the beauty of poetry! And we are especially pleased to be joined – at least until his court date – by the very famous Mr. Edgar Allan Poe! So witness the power of true criminal reclamation here at Mount Hope Penitentiary! And remember: for the worst of sinners, there’s always Hope. • The Raven • The Cask of Amontillado • Dream Within a Dream • To—Violet Vane • The Conqueror Worm • To Fanny • Romance • Sonnet to My Mother There may be other poems from but those shall be a surprise. Tremble and enjoy. Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849): Timeline– 1809 Edgar Poe was born in Boston to itinerant actors on January 19. 1810 Edgar’s father died (may well have deserted the family before this point), leaving mother to care for Edgar and his brother and sister alone. -

How Poe's Life Leaked Into His Works Ellie Quick Ouachita Baptist University

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita English Class Publications Department of English 11-25-2014 How Poe's Life Leaked into His Works Ellie Quick Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/english_class_publications Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Quick, Ellie, "How Poe's Life Leaked into His Works" (2014). English Class Publications. Paper 5. http://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/english_class_publications/5 This Class Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Class Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Quick 1 Ellie Quick Prof. Pittman American Lit I November 25th, 2014 How Poe’s Life Leaked into His Works Ask anyone about the author Edgar Allan Poe and most likely everyone will have a different opinion of him. Opinions on Poe range from a crazy, mad drunk to a genius, classic, thrilling author. There is no doubt that as an author Poe was different than other authors in his time, he is commonly referred to as the “father of modern mystery” and originator of science fiction stories (Olney 416). Much of Poe’s works reflect his life and who he was as a person. Poe began writing in 1832, publishing his first story anonymously. The recurrence of eerie themes in Poe’s writings brought much controversy; Poe’s works were the first of its kind. Poe’s stories have supernatural events in them, many involving death or life beyond death. -

The Oedipus Myth in Edgar A. Poe's "Ligeia" and "The Fall of the House of Usher"

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1996 The ediO pus myth in Edgar A. Poe's "Ligeia" and "The alF l of the House of Usher" David Glen Tungesvik Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Tungesvik, David Glen, "The eO dipus myth in Edgar A. Poe's "Ligeia" and "The alF l of the House of Usher"" (1996). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16198. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16198 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Oedipus myth in Edgar A. Poe's "Ligeia" and "The Fall of the House of Usher" by David Glen Tungesvik A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Literature) Major Professor: T. D. Nostwich Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1996 Copyright © David Glen Tungesvik, 1996. All rights reserved. ii Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Masters thesis of David Glen Tungesvik has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ... .................................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 "LlGEIA" UNDISCOVERED ............................................................................... 9 THE LAST OF THE USHERS ......................................................................... -

Edgar Allan Poe Simon & Schuster Classroom Activities for the Enriched Classic Edition of the Great Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe

Simon & Schuster Classroom Activities For the Enriched Classic edition of The Great Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe Simon & Schuster Classroom Activities For the Enriched Classic edition of The Great Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe Each of the three activities includes: • NCTE standards covered • An estimate of the time needed • A complete list of materials needed • Step-by-step instructions • Questions to help you evaluate the results The curriculum guide and many other curriculum guides for Enriched Classics and Folger Shakespeare Library editions are available on our website, www.simonsaysteach.com. The Enriched Classic Edition of The Great Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe includes: • An introduction that provides historical context and outlines the major themes of the work • Critical excerpts • Suggestions for further reading Also Available: More than fifty classic works are now available in the new Enriched Classic format. Each edition features: • A concise introduction that gives the reader important background information • A chronology of the author’s life and work • A timeline of significant events that provides the book’s historical context • An outline of key themes and plot points to help readers form their own interpretations • Detailed explanatory notes • Critical analysis, including contemporary and modern perspectives on the work • Discussion questions to promote lively classroom discussion • A list of recommended related books and films to broaden the reader’s experience Recent additions to the Enriched Classic series include: • Beowulf, Anonymous, ISBN 1416500375, $4.95 • The Odyssey, Homer, ISBN 1416500367, $5.95 • Dubliners, James Joyce, ISBN 1416500359, $4.95 • Oedipus the King, Sophocles, ISBN 1416500332, $5.50 • The Souls of Black Folks, W.E.B. -

The Representation of Women in the Works of Edgar Allan Poe

Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Elien Martens The Representation of Women in the Works of Edgar Allan Poe Masterproef voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde Engels - Spaans Academiejaar 2012-2013 Promotor Prof. Dr. Gert Buelens Vakgroep Letterkunde 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Prof. Dr. Gert Buelens, without whom this dissertation would not have been possible. His insightful remarks, useful advice and continuous guidance and support helped me in writing and completing this work. I could not have imagined a better mentor. I would also like to thank my friends, family and partner for supporting me these past months and for enduring my numerous references to Poe and his works – which I made in every possible situation. Thank you for being there and for offering much-needed breaks with talk, coffee, cake and laughter. Last but not least, I am indebted to one more person: Edgar Allan Poe. His amazing – although admittedly sometimes rather macabre – stories have fascinated me for years and have sparked my desire to investigate them more profoundly. To all of you: thank you. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 6 1. The number of women in Poe’s poems and prose ..................................................................... 7 2. The categorization of Poe’s women ................................................................................................ 9 2.1 The classification of Poe’s real women – BBC’s Edgar Allan Poe: Love, Death and Women......................................................................................................................................................... 9 2.2 The classification of Poe’s fictional women – Floyd Stovall’s “The Women of Poe’s Poems and Tales” ................................................................................................................................. 11 3. -

A New Genre Emerges: the Creation and Impact of Dark Romanticism

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita English Class Publications Department of English 12-1-2015 A New Genre Emerges: The rC eation and Impact of Dark Romanticism Morgan Howard Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/english_class_publications Recommended Citation Howard, Morgan, "A New Genre Emerges: The rC eation and Impact of Dark Romanticism" (2015). English Class Publications. Paper 12. http://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/english_class_publications/12 This Class Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Class Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Howard 1 Morgan Howard Professor Pittman American Literature I 1 December 2015 A New Genre Emerges: The Creation and Impact of Dark Romanticism Readers around the world pick up on the nuances of literature. We see the differences between genres, sometimes subtle and sometimes not so subtle. We can see how authors often insert their own experiences, beliefs, and personalities into their works. This makes each book unique and pleasurable while remaining similar to thousands of others. Many who study American literature know that different styles and literary movements influence authors. It is easy to see the impact of Puritan thinking in the seventeenth century or of Transcendentalism in the first few decades of the nineteenth century. Authors usually do not combine genres. However, three authors—Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Herman Melville—each combine two styles, Romanticism and the Gothic, that at first glance appear radically opposite. -

Poe's Challenge to Sentimental Literature Through Themes of Obsession, Paranoia, and Alienation

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in English 5-2020 Poe's Challenge to Sentimental Literature through Themes of Obsession, Paranoia, and Alienation Michelle Winters Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds Recommended Citation Winters, Michelle, "Poe's Challenge to Sentimental Literature through Themes of Obsession, Paranoia, and Alienation" (2020). Culminating Projects in English. 162. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds/162 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in English by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Poe’s Challenge to Sentimental Literature through Themes of Obsession, Paranoia, and Alienation by Michelle Winters A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in English Studies May, 2020 Thesis Committee: Monica Pelaez, Chairperson Judith Dorn Maria Mikolchak 2 Abstract Edgar Allan Poe’s works have withstood the test of time. Converse to the popular sentimental literature of the time, Poe’s works offer a more intimate and psychological approach. It is through the inner dialogue of his speakers and narrators that Poe challenges the emotional appeal of sentimental literature. By looking at Poe’s poetry and short stories, the common themes of obsession, paranoia, and alienation emerge. Through these themes, Poe’s works serve as cautionary tales to the incomplete nature of sentimental literature towards the full human condition. -

Illuminating Poe

Illuminating Poe The Reflection of Edgar Allan Poe’s Pictorialism in the Illustrations for the Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades des Doktors der Philosophie beim Fachbereich Sprach-, Literatur- und Medienwissenschaft der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Christian Drost aus Brake Hamburg, 2006 Als Dissertation angenommen vom Fachbereich Sprach-, Literatur- und Medienwissenschaft der Universität Hamburg aufgrund der Gutachten von Prof. Dr. Hans Peter Rodenberg und Prof. Dr. Knut Hickethier Hamburg, den 15. Februar 2006 For my parents T a b l e O f C O n T e n T s 1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 2 Theoretical and methodical guidelines ................................................................ 5 2.1 Issues of the analysis of text-picture relations ................................................. 5 2.2 Texts and pictures discussed in this study ..................................................... 25 3 The pictorial Poe .......................................................................................... 43 3.1 Poe and the visual arts ............................................................................ 43 3.1.1 Poe’s artistic talent ......................................................................... 46 3.1.2 Poe’s comments on the fine arts ............................................................. 48 3.1.3 Poe’s comments on illustrations ........................................................... -

An Investigation of the Aesthetics of Edgar Allan Poe

Indefinite Pleasures and Parables of Art: An Investigation of the Aesthetics of Edgar Allan Poe The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:37945134 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Indefinite Pleasures and Parables of Art: An Investigation of the Aesthetics of Edgar Allan Poe By Jennifer J. Thomson A Thesis in the Field of English for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2018 Copyright 2018 Jennifer J. Thomson Abstract This investigation examines the origins and development of Edgar Allan Poe’s aesthetic theory throughout his body of work. It employs a tripartite approach commencing with the consideration of relevant biographical context, then proceeds with a detailed analysis of a selection of Poe’s writing on composition and craft: “Letter to B—,” “Hawthorne’s Twice-Told Tales,” “The Philosophy of Composition,” “The Poetic Principle,” and “The Philosophy of Furniture.” Finally, it applies this information to the analysis of selected works of Poe’s short fiction: “The Assignation,” “The Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Oval Portrait,” “The Domain of Arnheim,” and “Landor’s Cottage.” The examination concludes that Poe’s philosophy of art and his metaphysics are linked; therefore, his aesthetic system bears more analytical weight in the study of his fiction than was previously allowed. -

Myriad Approaches to Death in Edgar Allan Poe's Tales of Terror Jenni A

Regis University ePublications at Regis University All Regis University Theses Spring 2011 Living in the Mystery: Myriad Approaches to Death in Edgar Allan Poe's Tales of Terror Jenni A. Shearston Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Shearston, Jenni A., "Living in the Mystery: Myriad Approaches to Death in Edgar Allan Poe's Tales of Terror" (2011). All Regis University Theses. 550. https://epublications.regis.edu/theses/550 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Regis University Theses by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regis University Regis College Honors Theses Disclaimer Use of the materials available in the Regis University Thesis Collection (“Collection”) is limited and restricted to those users who agree to comply with the following terms of use. Regis University reserves the right to deny access to the Collection to any person who violates these terms of use or who seeks to or does alter, avoid or supersede the functional conditions, restrictions and limitations of the Collection. The site may be used only for lawful purposes. The user is solely responsible for knowing and adhering to any and all applicable laws, rules, and regulations relating or pertaining to use of the Collection. All content in this Collection is owned by and subject to the exclusive control of Regis University and the authors of the materials. -

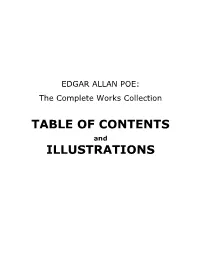

Table of Contents Illustrations

EDGAR ALLAN POE: The Complete Works Collection TABLE OF CONTENTS and ILLUSTRATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 – Edgar Allan Poe – An Appreciation Chapter 2 – Edgar Allan Poe by James Russell Lowell Chapter 3 – Death of Edgar Allan Poe by N.P. Willis Chapter 4 – The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfaal Chapter 5 – Notes to Hans Pfaal Chapter 6 – The Gold-Bug Chapter 7 – Four Beasts In One – The Homo-Cameleopard Chapter 8 – The Murders In the Rue Morgue Chapter 9 – The Mystery of Marie Roget Chapter 10 – The Balloon Hoax Chapter 11 – Ms. Found In a Bottle Chapter 12 – The Oval Portrait Chapter 13 – The Purloined Letter Chapter 14 – The Thousand and Second Tale of Scheherazade Chapter 15 – A Descent into the Maelstrom Chapter 16 – Von Kempelen and His Discovery Chapter 17 – Mesmeric Revelation Chapter 18 – The Facts In the Case of M. Valdemar Chapter 19 – The Black Cat Chapter 20 – The Fall of the House of Usher Chapter 21 – Silence: a Fable Chapter 22 – The Masque of the Red Death Chapter 23 – The Cask of Amontillado Chapter 24 – The Imp of the Perverse Chapter 25 – The Island of the Fay Chapter 26 – The Assignation Chapter 27 – The Pit and the Pendulum Chapter 28 – The Premature Burial Chapter 29 – The Domain of Arnheim Chapter 30 – Landor’s Cottage Chapter 31 – William Wilson Chapter 32 – The Tell-Tale Heart Chapter 33 - Berenice Chapter 34 - Eleonora Chapter 35 – Narrative of A. Gordon Pym - Introduction Chapter 36 – Narrative of A. Gordon Pym – Chapter 1 Chapter 37 – Narrative of A. Gordon Pym – Chapter 2 Chapter 38 – Narrative of A. -

A Contrastive Study of the Female Portrait in Some of Nathaniel

! " # ! " $ %&&' 2 ' 2 2 ) ()"*+ )(* 2 : ,*)$($ 2 = -)*+*.* , 2 2 J * ) )*"$ 2 2 '' -*".. 2 ') -"$ /..0"* 2 2 (' ) 1++( #.. 2 2 (= .**" 2 2 )' ) /(")-"# 2 ): .( ( 2 )J * .$(*$ 2 2 *) /(/.(* ", 2 *: My deepest gratitude to Professor Andrès Ferrada who has shared his knowledge and experience. Without his guidance this project would not have Been possible. # $ % "& ' ( # $ % "& To Karinette. Thank you for your love and support. Thank you for your for inspiring me with new ideas. # $ % "& ) * # $ % "& ()"*+ )(* ()"*+ )(* + &, + + , + & - + . ! / 0 + - + / + % + + + + + -+ + 1 + 2 3 + + - + +2 & + & . ! 4 56 7 8'9):;% 5. 7 8'9*';% 5 7 8'9)9;% & 0 + - + 4 56 < 7 8'9)=; 5+ > $ 7 8'9)?;% 5+ < +@7 8'9*);3 .+ + + & & & + 1 - + + - 3 >+ + & + - + + 0 +1 % - + + - + + + 1 A + 3 > - + / - @% + % +2 2 + + + & 2 + + ! 2 + 3 ! & - + 2 - + + + 2 2 % + + +2 % - @ - & + + + & + 3 + 2 % + + + % % + 2 + 3 + - -+ ! / + + - - % -% + 3 + + 2 ! / - @ + - -+ + + + - + + + + + 3 # + + # $ % "& :