Is Agentive Experience Compatible with Determinism?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

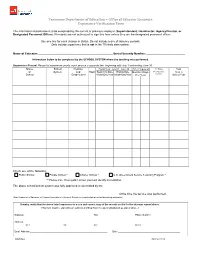

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

As in Milan Kundera's the Unbearable Lightness of Being

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Postmodernism and the Concept of Kitsch- As in Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being Dr.Shanthichitra Associate Professor & Head, Dept. of English, College of Science and Humanities SRMIST, Chennai, India Abstract: The concept of Kitsch is one of the difficult concepts which has been so easily handles by Milan Kundera in his incredible work of art – The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Culturally accepted words and situations vs. the words which are labeled as grotesque points out that peculiar point which deviates the ordinary to sublimity. This paper studies that ordinary which is ignored in culture through Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Keywords: Kitsch, Postmodernism, Phenomenology, Milan Kundera, Ideologies and Culture. When I came across the concept of Taipei modern Toilet diner, I was reminded of Milan Kundera’s Kitsch…This Modern Toilet diner is one of chain of themed eateries in Taiwan appealing to largely the youngsters of the city. This diner has greater relevance to the modern culture, culture in which youngsters call each other by bad words out of love…they have overcome all the grotesques!? Are they above all the human hurts?! Or is it an effort to deviate from kitsch?! Milan Kundera in his The Unbearable Lightness of Being talks about the concept of Kitsch. Kitsch is a German word that’s been adopted by a number of other languages, including English. It refers primarily to art that is overly sentimental or melodramatic, and so refers to aesthetics. What’s interesting is the way Kundera uses the concept in his novel, not to talk about art, but to talk about political ideology and about life. -

A Phenomenological Investigation of Lighting in Built Environments

Think About Thinking About Light: A Phenomenological Investigation of Lighting in Built Environments A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University, Ontario, Canada. Taylor Stone 210601706 July 26, 2011 Student Signature: _____________________________________ Supervisor Signature: __________________________________ (Peter Timmerman) Stone i Table of Contents Abstract ii Foreword iii Acknowledgements iv 1. Introduction: In Search of Light 1 Times Square at Night… Light as a Topic of Inquiry… Note on Paper Structure 2. Questioning Architecture: Ecological Design as a Qualitative Field of Inquiry 8 Environmentalism and Architecture… This is Not About Architecture 3. Phenomenology: Theoretical Framework 15 In Search of the Experiential Basis of Experiences… Architectural Phenomenology… Ecophenomenology… Questions of Scale 4. Finding the Light: Experiential and Interpretive Understandings 25 Seeing the Light… Some Thoughts on Light as Metaphor… Metaphors Buried but Not Forgotten… Seeing the Light, Almost 5. Dundas Square: Big City Lights 46 The City at Night… Light and Space, and Darkness… A Cosmos Unto Itself 6. The Terrence Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research: A World Without Windows 63 A World of Glass… Allan Gardens… Inside Out, Outside In 7. St. Gabriel’s Passionist Parish: In Light of Religious Experience 81 Light, Materialization, Colour… The Light of God in the Dark Ages… A New Religious Experience… Cathedral Church of St. James 8. Conclusion: Reflections 105 Summary and Concluding Remarks… Looking Back… Looking Forward… Coda: Still Searching Appendix 112 1) Research Method 2) Building Credits Works Cited 119 Stone ii Abstract This Major Paper is a phenomenological investigation of lighting in built environments. -

Philosophy of Chemistry: an Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 811 SE 062 822 AUTHOR Erduran, Sibel TITLE Philosophy of Chemistry: An Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education. PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at the History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Conference (5th, Pavia, Italy, September, 1999). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chemistry; Educational Change; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Philosophy; Science Curriculum; *Science Education; *Science Education History; *Science History; Scientific Principles; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods ABSTRACT Traditional applications of history and philosophy of science in chemistry education have concentrated on the teaching and learning of "history of chemistry". This paper considers the recent emergence of "philosophy of chemistry" as a distinct field and explores the implications of philosophy of chemistry for chemistry education in the context of teaching and learning chemical models. This paper calls for preventing the mutually exclusive development of chemistry education and philosophy of chemistry, and argues that research in chemistry education should strive to learn from the mistakes that resulted when early developments in science education were made separate from advances in philosophy of science. Contains 54 references. (Author/WRM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 1 PHILOSOPHY OF CHEMISTRY: AN EMERGING FIELD WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR CHEMISTRY EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research and improvement BEEN GRANTED BY RESOURCES INFORMATION SIBEL ERDURAN CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproducedas ceived from the person or organization KING'S COLLEGE, UNIVERSITYOF LONDON originating it. -

Existential Investigation: the Unbearable Lightness of Being and History

Existential Investigation: The Unbearable Lightness of Being and History Gregory Kimbrell To fully understand a piece of writing requires a grasp of its historical context. It follows then that an understanding of Czechoslovak history is necessary for the full appreciation of Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Kundera, however, disagrees.1 What is a reader who is seeking to do an historical analysis of Kundera’s novel to make of his opinion, and what implications does his opinion bear on the historical analysis itself? Even if the contents of the novel cannot be directly related to Czechoslovak history, it may nevertheless be the case that Kundera’s opinion is itself rooted in historical circumstances. To determine the relation of Kundera and The Unbearable Lightness of Being to history, one must first make sense of his attitude towards history and the ways in which it has influenced the creation of his novel. Kundera explains in his non-fiction work The Art of the Novel that history has traditionally been thought to be an expression of the progress of humankind through time which can be explained rationally. To Kundera, this definition is not simply idealistic but downright delusional. Having experienced life under Soviet totalitarianism, he believes that there can be no rational explanation for what he found to be the absurdities and cruelties of the regime. “[W]hy does Russia today want to dominate the world?” Kundera wrote. “To be richer? Happier? Not at all. The aggressivity of [this] force is thoroughly disinterested…it is pure irrationality.”2 To appropriately comprehend history, Kundera feels that it “must be understood…as an existential situation.”3 He draws his Chrestomathy: Annual Review of Undergraduate Research at the College of Charleston Volume 1, 2002: pp. -

Freewill and Determinism: the African Perspective and Experience

Global Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.3, No.2, pp.75-82, February 2015 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) FREEWILL AND DETERMINISM: THE AFRICAN PERSPECTIVE AND EXPERIENCE Augustine Chidi Igbokwe, Department of Philosophy, Caritas University, Amorji – Nike P.M.B 01784, Enugu Enugu State – Nigeria. ABSTRACT: Whether Freewill and/or determinism has been an age long heated debate in the history of Western philosophy. The African metaphysical enquiry attempts a resolution by establishing a complementarity parlance between the two. Reality then becomes a paradox of harmony of opposites. In the midst of this harmony, a realization comes that the more a society turns modern, the more freedom is identified, subjecting deterministic tendencies to the periphery. As Africa is on the process to modernity, the system of communalism that had hitherto served Africa now gives way to individualism. In the same vein, there is need for a conscious change from unorganized but effective brotherhood to corporate and efficient governance to synergize this paradigm shift KEYWORDS: Freewill; Determinism; Communalism; Individualism; Free-Determinism. INTRODUCTION The philosophical argument on freewill and determinism which dates back to the ancient period still takes the front burner in our philosophical discourse today. How free are our actions and the choices we make? This question becomes pertinent when we juxtapose it with the long assumed assertion that every effect has a cause. If our actions as effects are all caused, then how morally responsible are we in our actions? This is usually the major paradox in the discourse on freewill and determinism and this is the major rationale behind the insistence on the heated debate. -

Perceptual Causality, Counterfactuals, and Special Causal Concepts

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 19/10/2011, SPi 3 Perceptual Causality, Counterfactuals, and Special Causal Concepts Johannes Roessler On one view, an adequate account of causal understanding may focus exclusively on what is involved in mastering general causal concepts (concepts such as ‘x causes y’ or ‘p causally explains q’). An alternative view is that causal understanding is, partly but irreducibly, a matter of grasping what Anscombe called special causal concepts, con- cepts such as ‘push’, ‘flatten’,or‘knock over’. We can label these views generalist vs particularist approaches to causal understanding. It is worth emphasizing that the contrast here is not between two kinds of theories of the metaphysics of causation, but two views of the nature and perhaps source of ordinary causal understanding. One aim of this paper is to argue that it would be a mistake to dismiss particularism because of its putative metaphysical commitments. I begin by formulating an intuitively attractive version of particularism due to P.F. Strawson, a central element of which is what I will call na¨ıve realism concerning mechanical transactions. I will then present the account with two challenges. Both challenges reflect the worry that Strawson’s particularism may be unable to acknowledge the intimate connection between causa- tion and counterfactuals, as articulated by the interventionist approach to causation. My project will be to allay these concerns, or at least to explore how this might be done. My (tentative) conclusion will be that Strawson’sna¨ıve realism can accept what interventionism has to say about ordinary causal understanding, and that intervention- ism should not be seen as being committed to generalism. -

A Defense of Ethical Relativism One Entry in a Long Series of Possible Adjustments

A Defense of Ethical Relativism one entry in a long series of possible adjustments. These adjustments, whether they are in mannerisms like the ways of showing RUTH BENEDICT anger, or joy, or grief in any society, or in major human drives like those of sex, prove to be far more variable than experience in any one culture would suggest. In From Benedict, Ruth "Anthropology and the Abnormal," Journal of General Psychology, 10, 1934. certain fields, such as that of religion or of formal marriage arrangements, these wide limits of variability are well known and can be fairly described. In others it is Ruth Benedict (1887-1948), a foremost American anthropologist, taught at not yet possible to give a generalized account, but that does not absolve us of the Columbia University, and she is best known for her book Pattern of Culture task of indicating the significance of the work that has been done and of die (1935). Benedict views social systems as communities with common beliefs problems that have arisen. and practices, which have become integrated patterns of ideas and practices. One of these problems relates to the customary modern normal-abnormal Like a work of art, a culture chooses which theme from its repertoire of categories and our conclusions regarding them. In how far are such categories basic tendencies to emphasize and then produces a grand design, favoring culturally determined, or in how far can we with assurance regard them as absolute? those tendencies. The final systems differ from one another in striking ways, In how far can we regard inability to function socially as abnormality, or in how far but we have no reason to say that one system is better than another. -

What Is Meant by “Christian Dualism” (Genuine Separation

Jeremy Shepherd October 15, 2004 The Friday Symposium Dallas Baptist University “Christian Enemy #1: Dualism Exposed & Destroyed” “The Fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge, but fools despise wisdom and discipline.” - Proverbs 1:7 “Christianity is not a realm of life; it’s a way of life for every realm”1 Introduction When I came to Dallas Baptist University I had a rather violent reaction to what I thought was a profound category mistake. Coming from the public school system, I had a deeply embedded idea of how “religious” claims ought to relate, or should I say, ought not to relate, with “worldly affairs.” To use a phrase that Os Guinness frequently uses, I thought that “religion might be privately engaging but publicly irrelevant.”2 I was astonished at the unashamed integration of all these “religious” beliefs into other realms of life, even though I myself was a Christian. The key word for me was: unashamed. I thought to myself, “How could these people be so shameless in their biases?” My reaction to this Wholistic vision of life was so serious that I almost left the university to go get myself a “real” education, one where my schooling wouldn’t be polluted by all of these messy assumptions and presuppositions, even if they were Christian. My worldview lenses saw “education” as something totally separate from my “faith.” I was a model student of the American public school system, and like most other students, whether Christian or not, the separation of “church/state” and “faith/education” was only a small part of something much deeper and much more profound, the separation of my “faith” from the rest of my “life.” Our public schools are indoctrinating other students who have this same split-vision3, in which “faith” is a private thing, which is not to be integrated into the classroom. -

Perceptual Variation and Relativism

1 Perceptual Variation and Relativism John Morrison 1. Introduction According to Sextus, children perceive brighter colors than their grandparents (Outlines of Scepticism 1.105). Suppose that Sextus is right, and that Jacob perceives brighter colors than Sarah, his grandmother. In partic- ular, suppose that Jacob and Sarah are looking at the same stone tile, and that while Sarah has the kind of perception you have when you look at the square on the left in Figure 1.0, Jacob has the kind of perception you have when you look at the square on the right. Whose perception of the tile is accurate, Jacob’s or Sarah’s? Sarah Jacob Figure 1.0 Sextus rejects the standard responses. One response is that neither of their perceptions is accurate, because the tile isn’t really colored. Sextus attributes this response to Democritus (Outlines 1.213, 2.63; see also Against the Logicians 1.135– 40). Sextus objects that we would then know some- thing about the tile, namely that it is not colored, and that this conflicts with his skeptical view that we can’t know anything about external objects, not even whether they are or are not colored (Outlines 1.15). But one needn’t be a skeptic like Sextus to find this first response objectionable. An influential non- skeptical objection is that it’s central to the way we think and talk that John Morrison, Perceptual Variation and Relativism In: Epistemology After Sextus Empiricus. Edited by: Katja Maria Vogt and Justin Vlasits, Oxford University Press (2020). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190946302.003.0002 14 Appearances and Perception objects are really colored, and that, by default, we should try to preserve these ways of thinking and talking (see, e.g., Lewis 1997, 325– 28; Johnston 1992, 221– 22; Cohen 2009, 15, 65).