The Outsiders Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literature, CO Dime Novels

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 068 991 CS 200 241 AUTHOR Donelson, Ken, Ed. TITLE Adolescent Literature, Adolescent Reading and the English Class. INSTITUTION Arizona English Teachers Association, Tempe. PUB DATE Apr 72 NOTE 147p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Road, Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock No. 33813, $1.75 non-member, $1.65 member) JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; v14 n3 Apr 1972 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Adolescents; *English; English Curriculum; English Programs; Fiction; *Literature; *Reading Interests; Reading Material Selection; *Secondary Education; Teaching; Teenagers ABSTRACT This issue of the Arizona English Bulletin contains articles discussing literature that adolescents read and literature that they might be encouragedto read. Thus there are discussions both of literature specifically written for adolescents and the literature adolescents choose to read. The term adolescent is understood to include young people in grades five or six through ten or eleven. The articles are written by high school, college, and university teachers and discuss adolescent literature in general (e.g., Geraldine E. LaRoque's "A Bright and Promising Future for Adolescent Literature"), particular types of this literature (e.g., Nicholas J. Karolides' "Focus on Black Adolescents"), and particular books, (e.g., Beverly Haley's "'The Pigman'- -Use It1"). Also included is an extensive list of current books and articles on adolescent literature, adolescents' reading interests, and how these books relate to the teaching of English..The bibliography is divided into (1) general bibliographies,(2) histories and criticism of adolescent literature, CO dime novels, (4) adolescent literature before 1940, (5) reading interest studies, (6) modern adolescent literature, (7) adolescent books in the schools, and (8) comments about young people's reading. -

Ampleteaching Unit™

Prestwick House SampleTeaching Unit™ Chapter-by-Chapter Study Guide Rumble Fish by S. E. Hinton • Learning objectives • Study Guide with short-answer questions • Background information • Vocabulary in context • Multiple-choice test • Essay questions • Literary terms A Tale of Two Cities CHARLES DICKENS Click here to learn more REORDER NO . XXXXXX about this Teaching Unit! Click here to find more Classroom Resources for this title! More from Prestwick House Literature Grammar and Writing Vocabulary Reading Literary Touchstone Classics College and Career Readiness: Writing Vocabulary Power Plus Reading Informational Texts Literature Teaching Units Grammar for Writing Vocabulary from Latin and Greek Roots Reading Literature Chapter-by-Chapter Study Guide Rumble Fish by S. E. Hinton • Learning objectives • Study Guide with short-answer questions • Background information • Vocabulary in context • Multiple-choice test • Essay questions • Literary terms P.O. Box 658, Clayton, DE 19938 www.prestwickhouse.com 800.932.4593 ISBN: 978-1-58049-466-3 Copyright ©2017 by Prestwick House Inc. All rights reserved. No portion may be reproduced without permission in writing from the publisher. Item No: 300968 Rumble Fish TEACHING UNIT Rumble Fish Note to the Teacher Rusty-James is a street-wise, tough kid who relies on his fighting ability rather than intel- ligence to get what he wants. His older brother, the Motorcycle Boy, is the toughest kid in the neighborhood, and Rusty-James hopes to be just like him some day. The Motorcycle Boy is calm in the face of chaos, relishes time alone, and keeps his emotions invisible to those around him. Rusty-James is the exact opposite of his brother. -

“Harry – Yer a Wizard” Exploring J

Wissenschaftliche Beiträge aus dem Tectum Verlag Reihe Anglistik Wissenschaftliche Beiträge aus dem Tectum Verlag Reihe Anglistik Band 6 Marion Gymnich | Hanne Birk | Denise Burkhard (Eds.) “Harry – yer a wizard” Exploring J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter Universe Tectum Verlag Marion Gymnich, Hanne Birk and Denise Burkhard (Eds.) “Harry – yer a wizard” Exploring J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter Universe Wissenschaftliche Beiträge aus demT ectum Verlag, Reihe: Anglistik; Bd. 6 © Tectum Verlag – ein Verlag in der Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2017 ISBN: 978-3-8288-6751-2 (Dieser Titel ist zugleich als gedrucktes Werk unter der ISBN 978-3-8288-4035-5 und als ePub unter der ISBN 978-3-8288-6752-9 im Tectum Verlag erschienen.) ISSN: 1861-6859 Umschlaggestaltung: Tectum Verlag, unter Verwendung zweier Fotografien von Schleiereule Merlin und Janna Weinsch, aufgenommen in der Falknerei Pierre Schmidt (Erftstadt/Gymnicher Mühle) | © Denise Burkhard Informationen zum Verlagsprogramm finden Sie unter www.tectum-verlag.de Bibliografische Informationen der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Angaben sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available online at http://dnb.ddb.de. Contents Hanne Birk, Denise Burkhard and Marion Gymnich ‘Happy Birthday, Harry!’: Celebrating the Success of the Harry Potter Phenomenon ........ 7 Marion Gymnich and Klaus Scheunemann The ‘Harry Potter Phenomenon’: Forms of World Building in the Novels, the Translations, the Film Series and the Fandom ................................................................. 11 Part I: The Harry Potter Series and its Sources Laura Hartmann The Black Dog and the Boggart: Fantastic Beasts in Joanne K. -

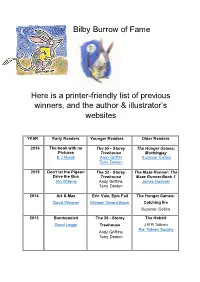

Bilby Burrow of Fame Here Is a Printer-Friendly List of Previous

Bilby Burrow of Fame Here is a printer-friendly list of previous winners, and the author & illustrator’s websites YEAR Early Readers Younger Readers Older Readers 2016 The book with no The 65 - Storey The Hunger Games: Pictures Treehouse Mockingjay B J Novak Andy Griffith Suzanne Collins Terry Denton 2015 Don't let the Pigeon The 52 - Storey The Maze Runner: The Drive the Bus Treehouse Maze Runner Book 1 Mo Willems Andy Griffiths James Dashner Terry Denton 2014 Art & Max Eric Vale, Epic Fail The Hunger Games: David Wiesner Michael Gerard Bauer Catching fire Suzanne Collins 2013 Bamboozled The 26 - Storey The Hobbit David Legge Treehouse J R R Tolkien The Tolkien Society Andy Griffiths Terry Denton 2012 The Cat in the Hat Diary of a Wimpy Kid The Hunger Games Dr Seuss Jeff Kinney Suzanne Collins 2011 Dewey: There’s a Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Percy Jackson and Cat in the Library the Ugly truth the Lightning Thief Jeff Kinney Vicki Myron Rick Riordan 2010 Zac Power: Poison Diary of a Wimpy Kid New Moon Island Jeff Kinney Stephenie H I Larry Meyer 2009 The Twits Pencil of Doom! Twilight Roald Dahl Andy Griffiths Stephenie Meyer 2008 Diary of a Wombat Just Shocking! Harry Potter and the Jackie French Andy Griffiths Deathly Hallows Bruce Whatley J K Rowling 2007 Ugly Fish The Cat on the Mat Eragon Kara LaReau is Flat Christopher Paolini Scott Magoon Andy Griffiths Terry Denton 2006 Baby Boomsticks Just Crazy! Harry Potter and the Margaret Wild Andy Griffiths Half-Blood Prince David Legge J K Rowling 2005 Old Tom's Holiday The Bad Book Harry Potter -

Nova Dahlén Severus Snape and the Concept of the Outsider

Estetisk-filosofiska fakulteten Nova Dahlén Severus Snape and the Concept of the Outsider Aspects of Good and Evil in the Harry Potter Series Engelska D-uppsats Termin: VT 2009 Handledare: Åke Bergvall Examinator: Mark Troy Karlstads universitet 651 88 Karlstad Tfn 054-700 10 00 Fax 054-700 14 60 [email protected] www.kau.se Table of contents Introduction 1 Severus Snape 2 Snape and Dumbledore 6 Snape and Voldemort 10 Snape and Harry 14 Conclusion 20 Works cited 22 Introduction J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series contains a large number of outsider characters, ranging from fun sidekicks and magical creatures to evil antagonists. The concept of outsiders has been argued to be one of the main themes in childhood fairy tales in general and in the Harry Potter novels in particular: as most children feel like outsiders sometime during their upbringing, they can identify with this concept (Heilman and Gregory 242; O’har 862; Ostry 89-90). The outsiders of the Harry Potter series may be defined as characters who, although they may have friends or relationships, are significant in how their primary function relies on their distance to others. Severus Snape is one of the most evident outsider characters in the novels, described as an unpleasant, ugly man portrayed with constant ambiguity: Seemingly working for both Lord Voldemort (the evil side) and the Order of the Phoenix (the good side), he is presented as a double agent with uncertain allegiances. However, when the truth is revealed in the very last pages of the series he is discovered to have been an undercover spy for the good side all along. -

Sample Pages

About This Volume M. Katherine Grimes The writers of Critical Insights: The Outsiders began our project LQWKH\HDU6(+LQWRQ¶VILUVWSXEOLVKHGQRYHOWXUQHGILIW\ Like Hinton herself, many of us waxed a bit nostalgic about a book from our past, one we read in our youth, probably at about the age when Hinton wrote her famous book. Now looking at The Outsiders as adults, we find it richer than we did when we first read it, filled with themes and concepts we missed when we found it just “a really JRRGERRN´ Laurie Adams wrote much of the background material on the book’s author, as well as researching the bibliographic material, works by and about S. E. Hinton. Because Ms. Adams’ HGXFDWLRQDO EDFNJURXQG LV LQ WKH ¿HOG RI FULPLQDO MXVWLFH KHU Historical Background chapter, “Lawyer Up, Ponyboy: Reconciling Delinquency Outcomes in S. E. Hinton’s The Outsiders with Trends LQ 0RGHUQ -XYHQLOH -XVWLFH´ H[SORUHV WKH OHJDO LVVXHV HVSHFLDOO\ crime and punishment, that the characters in The Outsiders might have faced in the mid-1960s and what they might face under similar circumstances today. Lana A. Whited and M. Katherine Grimes in the Critical Reception chapter look at what critics said about the novel when LWZDV¿UVWSXEOLVKHGDJDLQRQWKHERRN¶VIRUWLHWKDQQLYHUVDU\DQG on The Outsiders’ recent semicentennial. Both Dr. Whited and Dr. Grimes have also written additional essays for this volume. 'U:KLWHG¶VPDMRU¿HOGRIVWXG\LVWZHQWLHWKFHQWXU\%ULWLVK and American literature, and recently much of her writing has been about novels for children and adolescents, works including the Harry Potter and Hunger Games series. For this volume, she has written an essay about parallels among The Outsiders’ narrator, Ponyboy Curtis; the narrator and titular character of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn; and Stephen Daedelus, the protagonist of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man; her essay is vii called “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Greaser: The Outsiders as Künstlerroman´ In the essay “S. -

Se Hinton Was a Published Author

|| teachers@random || S.E. Hinton about this author By the time she was 17 years old, Susan Eloise Hinton was a published author. While still in high school in her hometown--Tulsa, Oklahoma--Hinton put in words what she saw and felt growing up and called it The Outsiders, a now classic story of two sets of high school rivals, the Greasers and the Socs (for society kids). Because her hero was a Greaser and outsider, and her tale was one of gritty realism, Hinton launched a revolution in young adult literature. Since her narrator was a boy, Hinton's publishers suggested that she publish under the name of S. E. Hinton; they feared their readers wouldn't respect a "macho" story written by a woman. Hinton says today, "I don't mind having two identities; in fact, I like keeping the writer part separate in some ways. And since my alter ego is clearly a 15-year-old boy, having an authorial self that doesn't suggest a gender is just fine with me." Today, more than twenty-five years after its first publication, The Outsiders ranks as a classic, still widely read and one of the most important and taboo-breaking books in the field. Finally, someone was writing about the real concerns and emotions of a teenager. The Outsiders marked the beginning of a new kind of realism in books written for the young adult market, and Hinton's next four books followed suit. http://randomhouse.com/teachers/authors/sehi.html (1 of 5) [1/31/2001 1:32:36 AM] || teachers@random || She wrote her second book while she was in college at the University of Tulsa, studying to be a teacher. -

Rumble Fish Based on the Book by S

TEACHER’S PET PUBLICATIONS LITPLAN TEACHER PACK™ for Rumble Fish based on the book by S. E. Hinton Written by Barbara M. Linde, MA Ed. © 1996 Teacher’s Pet Publications All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-1-60249-242-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS - Rumble Fish Introduction 5 Unit Objectives 7 Unit Outline 8 Reading Assignment Sheet 9 Study Questions 13 Study/Quiz Questions (Multiple Choice) 21 Prereading Vocabulary Worksheets 37 Lesson One (Introductory Lesson) 49 Nonfiction Assignment Sheet 54 Oral Reading Evaluation Form 56 Writing Assignment 1 60 Writing Evaluation Form 61 Writing Assignment 2 65 Extra Writing Assignments/Discussion ?s 69 Writing Assignment 3 76 Vocabulary Review Activities 78 Unit Review Activities 79 Unit Tests 87 Unit Resource Materials 123 Vocabulary Resource Materials 139 A FEW NOTES ABOUT THE AUTHOR Courtesy of Compton's Learning Company Hinton, S. E. (Susan Eloise Hinton) (born 1950), U. S. Author, born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1950. As a young writer, Hinton decided to write under her initials in order to deflect attention from her gender. She set out to write about the difficult social system that teenagers create among themselves. Her books struck a chord with readers who saw in her characters many elements of this system that existed in their own schools and towns. In 1967, while she was still in high school, Hinton published her first book, The Outsiders. The story of confrontation between rival groups of teenagers was immediately successful with critics and young readers, and it won several awards. There was some controversy about the level of violence in the novel and in her other works, but Hinton was praised for her realistic and explosive dialogue. -

THE OUTSIDERS a Stage Play Written by Christopher Sergel Based Upon the Novel by S.E

Prime Stage Theatre Resource Guide THE OUTSIDERS A stage play written by Christopher Sergel based upon the novel by S.E. Hinton Directed by Scott P. Calhoon March 6, 2020 - March 15, 2020 A coming-of-age story where Ponyboy, the Greasers & Socs learn valuable lessons about belonging, friendship, family and goodness Prime Stage Theatre Performances are located at the New Hazlett Theater Center for Performing Arts, Pittsburgh, PA Welcome to Prime Stage Theatre’s 2019-2020 Season See Me for Who I Am Bringing Literature to Life! Dear Educator, We are pleased to bring you the The Outsiders, a modern classic written for the stage by Christopher Sergel from the book by S.E. Hinton, our second exciting production of the season. All literature produced by Prime Stage is always drawn from middle and secondary reading lists and themes are in the current Pennsylvania curriculum. This Resource Guide is designed to provide historical background and context, classroom activities and curricular content to help you enliven your students’ experience with the literature and the theatre. We encourage you to use the theatrical games and creative thinking activities, as well as the Theatre Etiquette suggested activities to spark personal connections with the themes and characters in the story of The Outsiders. If you have any questions about the information or activities in the guide, please contact me and I will be happy to assist you, and I welcome your suggestions and comments! Linda Haston, Education Director & Teaching Artist Prime Stage Theatre [email protected] The activities in this guide are intended to enliven, clarify and enrich the text as you read, and the experience as you watch the literature. -

S.E. Hinton: Biography

S.E. Hinton: Biography S.E. Hinton, was and still is, one of the most popular and best known writers of young adult fiction. Her books have been taught in some schools, and banned from others. Her novels changed the way people look at young adult literature. Susan Eloise Hinton was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma. She has always enjoyed reading but wasn't satisfied with the literature that was being written for young adults, which influenced her to write novels like The Outsiders. That book, her first novel, was published in 1967 by Viking. Once published, The Outsiders gave her a lot of publicity and fame, and also a lot of pressure. S.E. Hinton was becoming known as "The Voice of the Youth" among other titles. This kind of pressure and publicity resulted in a three year long writer's block. Her boyfriend (and now, her husband),who had gotten sick of her being depressed all the time, eventually broke this block. He made her write two pages a day if she wanted to go anywhere. This eventually led to That Was Then, This Is Now. That Was Then, This Is Now is known to be a much more well thought out book than The Outsiders. Because she read a lot of great literature and wanted to better herself, she made sure that she wrote each sentence exactly right. She continued to write her two pages a day until she finally felt it was finished in the summer of 1970, she got married a few months later. That Was Then, This is Now was published in 1971. -

Books Made Into Movies

Books Made into Movies AGES 11-14 Beautiful Creatures by Kami Garcia and Margaret Stohl Because of Winn-Dixie by Kate DiCamillo The Book Thief by Markus Zusak Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Paterson Charlie and the Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian by C.S. Lewis The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader by C.S. Lewis Coraline by Neil Gaiman Diary of a Wimpy Kid by Jeff Kinney Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Dog Days by Jeff Kinney Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Rodrick Rules by Jeff Kenney Divergent by Veronica Roth Dorothy of Oz by Roger S. Baum Ella Enchanted by Gail Carson Levine Enders Game by Orson Scott Card The Fault in Our Stars by John Green The Giver by Lois Lowry Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by J.K. Rowling Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets by J.K. Rowling Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban by J.K. Rowling Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire by J.K. Rowling Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix by J.K. Rowling Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince by J.K. Rowling Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows by J.K. Rowling Holes by Louis Sachar How to Eat Fried Worms by Thomas Rockwell How to Train Your Dragon by Cressida Cowell How to Train Your Dragon Book 2 by Cressida Cowell The Hunger Games Trilogy by Suzanne Collins (The Hunger Games, Catching Fire, and Mockingjay) The Indian in the Cupboard by Lynne Reid Banks Inkheart by Cornelia Funke James and the Giant Peach by Roald Dahl The Hobbit by J. -

Rumble Fish 1St Edition Ebook

RUMBLE FISH 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK S E Hinton | 9780385375689 | | | | | Rumble Fish 1st edition PDF Book Rumble fish S. I kind of feel like I wasted my time reading this. I kind of think hes cool because he doesnt care what people think of him. Very slightly bowed with slight wear on the spine ends and faint spots on the first few pages else about fine in a near fine dustwrapper with rubbing, some toning, and slight edgewear. Then, it goes back to when Steve and Rusty James talk years and years later, and Rusty-James is still very emotionally scarred. May Authenticity Guarantee. I think she improved on her first two novels, which wasn't easy to do because The Outsiders was pretty excellent not as big a fan of That Was Then This Was Now. Patterson the Cop. More information about this seller Contact this seller 9. It's about life turning into black and white. Buy It Now. Release Year. I then went on to read her That was then, this is now and liked that as well. It was like Hinton made up the author of his life, as I imagined how he strugged to continue without Motorcycle Boy, getting in many fights, drinking too much, etc. Edit page. He likes to think of himself as the best and expects others to think of him as the best. They have a knife fight where Rusty almost wins but is distracted by the arrival of The Motorcycle Boy; when Rusty-James looks at The Motorcycle Boy, Biff grabs the knife and slashes it across Rusty-James' side, leaving a long gash.